Heracles in Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Development of the Notion of Kalos Kagathos from Homer to Aristotle

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2006 A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle Geoffrey Coad University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Coad, G. (2006). A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle (Master of Philosophy (MPhil)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/13 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NOTION OF KALOS KAGATHOS FROM HOMER TO ARISTOTLE Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Geoffrey John Coad School of Philosophy and Theology University of Notre Dame, Australia December 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Declaration v Acknowledgements vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Fish Hook and Some Other Examples 6 The Sun – The Source of Beauty 7 Some Instances of Lack of Beauty: Adolf Hitler and Sharp Practices in Court 9 The Kitchen Knife and the Samurai Sword 10 CHAPTER 2: Homer 17 An Historical Analysis of the Phrase Kalos Kagathos 17 Herman Wankel 17 Felix Bourriott 18 Walter Donlan 19 An Analysis of the Terms Agathos, Arete and Other Related Terms of Value in Homer 19 Homer’s Purpose in Writing the Iliad 22 Alasdair MacIntyre 23 E. -

An Analysis of Heracles As a Tragic Hero in the Trachiniae and the Heracles

The Suffering Heracles: An Analysis of Heracles as a Tragic Hero in The Trachiniae and the Heracles by Daniel Rom Thesis presented for the Master’s Degree in Ancient Cultures in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Annemaré Kotzé March 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis is an examination of the portrayals of the Ancient Greek mythological hero Heracles in two fifth century BCE tragic plays: The Trachiniae by Sophocles, and the Heracles by Euripides. Based on existing research that was examined, this thesis echoes the claim made by several sources that there is a conceptual link between both these plays in terms of how they treat Heracles as a character on stage. Fundamentally, this claim is that these two plays portray Heracles as a suffering, tragic figure in a way that other theatre portrayals of him up until the fifth century BCE had failed to do in such a notable manner. This thesis links this claim with a another point raised in modern scholarship: specifically, that Heracles‟ character and development as a mythical hero in the Ancient Greek world had given him a distinct position as a demi-god, and this in turn affected how he was approached as a character on stage. -

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife Joel P. Christensen Brandeis University [email protected] Abstract This article examines the development of the theme of eris in Hesiod and Homer. Start- ing from the relationship between the destructive strife in the Theogony (225) and the two versions invoked in the Works and Days (11–12), I argue that considering the two forms of strife as echoing zero and positive sum games helps us to identify the cultural and compositional force of eris as cooperative competition. After establishing eris as a compositional theme from the perspective of oral poetics, I then argue that it develops from the perspective of cosmic history, that is, from the creation of the universe in Hes- iod’s Theogony through the Homeric epics and into its double definition in the Works and Days.To explore and emphasize how this complementarity is itself a manifestation of eris, I survey its deployment in our major extant epic poems. Keywords eris – competition – conflict – poetics – rivalry In Cypria fr. 1, Zeus fans “the flames of the great strife of the Trojan war / to lighten the [earth’s] burden with death” (ῥιπίσσας πολέμου μεγάλην ἔριν Ἰλιακοῖο, 5).* Similarly, in Hesiod (fr. 204 M-W), when strife divides the gods at the birth of Hermione—“all the gods were of two minds / because of the strife” (πάν- τες δὲ θεοὶ δίχα θυμὸν ἔθεντο / ἐξ ἔριδος, 94–95)—Zeus hastens the destruction of the Heroes: “And then he hastened to extinguish the great race of human * A version of this article was given at the Heartland Graduate Conference in Ancient Stud- ies at the University of Missouri in 2015. -

The Name of Penelope Whallon, William Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1960; 3, 2; Proquest Pg

The Name of Penelope Whallon, William Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1960; 3, 2; ProQuest pg. 57 The Name of Penelope William W hallon T HE TALE OF ODYSSEUS' RETURN would have been very different if his wife had not been known as Penelope. For the Homeric poems came from an age of aural etymologizing,l the minstrels who perfected the poems throughout centuries of storytelling found proper nouns as meaningful as common nouns, and certain phonetic associations at first fortuitous became inevitable. Shakespeare's Juli et by any other name than Capulet would have had greater fortune in love, but Penelope's name is even more vitally related to her biography. Now it is an obvious fact that a language built upon a rather small number of phonemes is almost necessarily going to include homonyms, and correspondence of sound alone is insufficient to indicate words as cognate. In present-day Norwegian, for example, the word for the duck, Anda (where the dental stop is no longer pronounced), does not compel any kind of dark reminiscence of the girl named Anna, and likewise the duck 7TTJVEAoljl need not be thought germane to Penelope,2 unless in the similarity there is a remnant from the dawn of time, when in a beast epic Penelope might actually have been a duck, Athene an owl, Hera a heifer, and Apollo a wolf. In the Homeric poems we possess, the 7TTJv€Aoljl and Penelope have no semantic relationship, and the coincidence of identical syllables is unimportant. Another word, however, has been commonly observed as apparently akin to the name of Pe nelope, and may have had a crucial bearing upon her career: this IMost notably in Od. -

The 'Trial by Water' in Greek Myth and Literature

Leeds International Classical Studies 7.1 (2008) ISSN 1477-3643 (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classics/lics/) © Fiona McHardy The ‘trial by water’ in Greek myth and literature FIONA MCHARDY (ROEHAMPTON UNIVERSITY) ABSTRACT: This paper discusses the theme of casting ‘unchaste’ women into the sea as a punishment in Greek myth and literature. Particular focus will be given to the stories of Danaë, Augë, Aerope and Phronime, who are all depicted suffering this punishment at the hands of their fathers. While Seaford (1990) has emphasized the theme of imprisonment which occurs in some of the stories involving the ‘floating chest’, I turn my attention instead to the theme of the sea. The coincidence in these stories of the threat of drowning for apparent promiscuity or sexual impurity with the escape of those girls who are innocent can be explained by the phenomenon of the ‘trial by water’ as evidenced in Babylonian and other early law codes (cf. Glotz 1904). Further evidence for this theory can be found in ancient novels where the trial of the heroine for sexual purity is often a key theme. The significance of chastity in the myths and in Athenian society is central to understanding the story patterns. The interrelationship of mythic and social ideals is drawn out in the paper. This paper examines the punishment of ‘unchaste’ women in Greek myth and literature, in particular their representation in Euripides’ fragmentary Augë, Cretan Women and Danaë. My focus is on punishments involving the sea, where it is possible to discern two interrelated strands in the tales.1 The first strand involves an angry parent condemning an errant daughter to be cast into the sea with the intention of drowning her. -

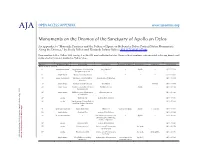

Supplemental Content: Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary Of

AJA OPEN ACCESS: APPENDIX www.ajaonline.org Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary of Apollo on Delos An appendix to “Honorific Practices and the Politics of Space on Hellenistic Delos: Portrait Statue Monuments Along the Dromos,” by Sheila Dillon and Elizabeth Palmer Baltes (AJA 117 [2013] 207–46). Base numbers follow Vallois 1923 (see fig. 3 in the AJA print-published article). Bases without numbers were recorded as having been found in the area but were not marked on Vallois’ plan. Base No. Monument Type Honorand(s) Dedicator(s) Reason(s) for Honor Dedicated to Sculptor(s) Reference(s) Bases set up ca. 250–200 5 equestrian statue Epigenes, son of Andron, the King Attalos I – Apollo – IG 11 4 1109 Pergamene general 8 single statue Donax, son of Apollonios – – – – IG 11 4 1202 16 group monument Aischylo(. .) and his father, Mennis, son of Nikarchos – – – IG 11 4 1168 Nikarchos 19 single statue female, Hellenistic queen? the Delians – – Thoinias IG 11 4 1088 20 single statue Autokles, son of Ainesidemos, Autokles, his son – Apollo – IG 11 4 1194 from Chalcidia 117.2) 25 single statue Phildemos, son of Pythermos Eumedes, his son – – – IG 11 4 1193 of Chalcedon 27 exedra family group demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1090 33 exedra family group of Jason, Eukleia, – – – – IG 11 4 1203 Timokleia, Straton, Timokleia, Sillis 41 victory monument Gallic dedication Attalos I(?) victory over Gauls Apollo (. .)epoiei IG 11 4 1110 50c single statue Aichmokritos demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1094 American Journal of Archaeology American 53 -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines. -

THE LAND of MYTH MECHANICS: This Adventure Was Designed As a ‘One Shot’ (I.E

2 3 ἄνδρα µοι ἔννεπε, µοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς µάλα πολλὰ πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν· πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω, πολλὰ δ᾽ ὅ γ᾽ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυµόν, ἀρνύµενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων. Homer’s Odyssey, Book 1, Lines 1-5 (ΟΜΗΡΟΥ ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑ, ΡΑΨΟΔΙΑ 1, ΣΤΙΧΟΙ 1-5) CREDITS INDEX Credits – The Land of Myth™ Team Written & Designed by: John R. Haygood Art Direction: George Skodras, Ali Dogramaci Who We Are .............................................................................................. 6 Cover Art: Ali Dogramaci What is this Product ................................................................................. 6 Proofreading & Editing: Vi Huntsman (MRC) This is a product created by Seven Thebes in collaboration with the Getty Museum Introduction ................................................................................................ 7 in Los Angeles, USA. Special thanks for the many hours of game testing and brainstorming: Safety and Consent .................................................................................. 10 Thanasis Giannopoulos, Alexandros Stivaktakis, Markos Spanoudakis About This Adventure Module .............................................................. 12 First Edition First Release: November 2020 Telemachos and His Quest ................................................................... 24 Character Sheets ...................................................................................... 26 Playtest Material V0.3 Please note that this -

Collection of Hesiod Homer and Homerica

COLLECTION OF HESIOD HOMER AND HOMERICA Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns, and Homerica This file contains translations of the following works: Hesiod: "Works and Days", "The Theogony", fragments of "The Catalogues of Women and the Eoiae", "The Shield of Heracles" (attributed to Hesiod), and fragments of various works attributed to Hesiod. Homer: "The Homeric Hymns", "The Epigrams of Homer" (both attributed to Homer). Various: Fragments of the Epic Cycle (parts of which are sometimes attributed to Homer), fragments of other epic poems attributed to Homer, "The Battle of Frogs and Mice", and "The Contest of Homer and Hesiod". This file contains only that portion of the book in English; Greek texts are excluded. Where Greek characters appear in the original English text, transcription in CAPITALS is substituted. PREPARER'S NOTE: In order to make this file more accessable to the average computer user, the preparer has found it necessary to re-arrange some of the material. The preparer takes full responsibility for his choice of arrangement. A few endnotes have been added by the preparer, and some additions have been supplied to the original endnotes of Mr. Evelyn-White's. Where this occurs I have noted the addition with my initials "DBK". Some endnotes, particularly those concerning textual variations in the ancient Greek text, are here ommitted. PREFACE This volume contains practically all that remains of the post- Homeric and pre-academic epic poetry. I have for the most part formed my own text. In the case of Hesiod I have been able to use independent collations of several MSS. by Dr. -

Athena in Athenian Literature and Cult Author(S): C

Athena in Athenian Literature and Cult Author(s): C. J. Herington Source: Greece & Rome, Vol. 10, Supplement: Parthenos and Parthenon (1963), pp. 61-73 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/826896 Accessed: 23-05-2020 06:06 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Classical Association, Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Greece & Rome This content downloaded from 73.97.157.116 on Sat, 23 May 2020 06:06:22 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms ATHENA IN ATHENIAN LITERATURE AND CULT By c. J. HERINGTON IF the subject of this article is to be fully appreciated, it is necessary to begin with a contrast. The still centre of Athena-worship at Athens lay towards the north side of the Acropolis, in the eastern half of the shrine nowadays called the Erechtheion, and in the predecessors of that building. There, from the time of our earliest records of Athenian history until the downfall of the classical world, sat an olive-wood image of Athena. It could be dressed and undressed, like a doll. -

Lecture 34 Good Morning and Welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology

Lecture 34 Good morning and welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology. Thank you for turning in your papers. When last we left off—this is going to be a short one—we were talking about how Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, was presented with a dilemma. If you’ll recall, at the very beginning of the Trojan War, all 1,000 ships of the Greek fleet were bottle up in the port city of Elis. They could not get out of the port because there was no wind. There was no wind because, as it turned out, the goddess Artemis was angry. Why? I don’t know that kind of a day. Agamemnon found out that he could get out of the city of Elis on one condition, if he offered his daughter Iphigenia as a sacrifice. Iphigenia, you will recall is one of the three children of Agamemnon and his loving wife Clytemnestra. To Agamemnon this was a no-brainer. To Agamemnon, obviously, he had to send for his daughter Iphigenia and sacrifice her so that he and his manly men and ships could get out of the port of Elis and kick Trojan you know what. Take Helen back, because, if he didn’t, Agamemnon would have been found lacking in arete. This is the first of two buzzwords I’m going to give you today. These are going to show up on all future examinations. Learn them, live them. Arete is the ancient Greek word for virtue. Interestingly enough, arete is the Greek word, the Latin virtue. Both are derived from the word for manliness. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable).