Season 2012-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fifth Event on the 1968-69 Allied Arts Music Series

FIFTH EVENT ON THE 1968-69 ALLIED ARTS MUSIC SERIES PROGRAM I. Sonata in C Major, Op. 53 (“Waldstein”).. ,L. Van Beethoven Allegro con brio Introduzione: Adagio molto Rondo: Allegretto moderato-Prestissimo Fantasiestucke, Op. 12 Robert Schumann Das Abends Aufschwung Warum? Grillen In der Nacht Fabel Traumeswirren Ende vom Lied INTERMISSION Members of the a'udience are earnestly requested to refrain from applauding between movements. Members of the audience who must leave the auditorium before the conclusion of the con cert are earnestly requested to do so between numbers, not during the performance. try NEDLOG, the orange drink that's made from fresh, sunripe oranges. if you're thirsty It's being served at all refreshment stands during intermission. ORCHESTRA HAU Sun. Aft., April 27 For one month each year a few audiences in North America and abroad are privi leged to hear a Trio which Time Magazine Eugene Isaac Leonard has called “the best in 50 years.” Three of the world's foremost instrumentalists, long associated in the private playing of cham ISTOMIN STERN ROSE ™° ber music for their own delight, take this time from their globe-circling solo tours piano violin cello to share this joy with the public. Tickets: $3.50, $4.50, $5.50, $6.50, $7.50 Mail orders to: Allied Arts Corp., 20 N. Wacker Drive, Chicago, III. 60606 Please include self addressed stamped envelopes with mail orders. ORCHESTRA HALL FRIDAY EVENING MAY 2 PflUh MflURIflT and his orchestra Tickets: $3.00, $4.00. $5.00, $6.00 Mail orders to: Allied Arts Corp. -

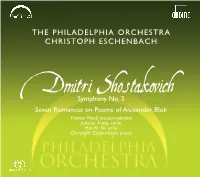

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

Isaac Stern Gala Performance! / Beethoven Triple Concerto Mp3, Flac, Wma

Isaac Stern Gala Performance! / Beethoven Triple Concerto mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Gala Performance! / Beethoven Triple Concerto Country: UK Released: 1965 Style: Classical MP3 version RAR size: 1416 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1698 mb WMA version RAR size: 1518 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 397 Other Formats: MP3 FLAC MIDI APE MP4 DTS MMF Tracklist Triple Concerto In C Major For Piano, Violin, Violincello And Orchestra, Op. 56 A Allegro B1 Largo B2 Rondo Alla Polacca Credits Cello – Leonard Rose Composed By – Ludwig van Beethoven Directed By – Eugene Ormandy Orchestra – Philadelphia Orchestra* Piano – Eugene Istomin Violin – Isaac Stern Barcode and Other Identifiers Label Code: D2S 320 Related Music albums to Gala Performance! / Beethoven Triple Concerto by Isaac Stern Brahms - Isaac Stern, Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra - Violin Concerto Beethoven, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy - Symphonie Nr. 5 Philadelphia Orchestra Conducted By Eugene Ormandy With Eugene Istomin - Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 In B-Flat For Piano And Orchestra, Op. 23 L. Van Beethoven : Zino Francescatti, Orchestre De Philadelphie , Direction Eugene Ormandy - Concerto En Ré Majeur Op. 61 Pour Violon Et Orchestre Isaac Stern / The Philadelphia Orchestra - Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto In D Major / Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto In E Minor Isaac Stern With Eugene Ormandy, Philadelphia Orchestra - Conciertos Para Violon The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, Eugene Istomin - Beethoven: Concerto No. 5 "Emperor" in E Flat Major For Piano and Orchestra, Op.73 Eugene Ormandy, The Philadelphia Orchestra - Beethoven Symphony No. 3 ("Eroica") The Istomin/Stern/Rose Trio - Beethoven's Archduke Trio Isaac Stern, The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy Conductor, Tchaikovsky - Mendelssohn - Violin Concerto In D Major • Violin Concerto In E Minor. -

Season 2012-2013

27 Season 2012-2013 Sunday, October 28, at 3:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra 28th Season of Chamber Music Concerts—Perelman Theater Mozart Duo No. 1 in G major, K. 423, for violin and viola I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Rondo: Allegro William Polk Violin Marvin Moon Viola Dvorˇák String Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 97 I. Allegro non tanto II. Allegro vivo III. Larghetto IV. Finale: Allegro giusto Kimberly Fisher Violin William Polk Violin Marvin Moon Viola Choong-Jin Chang Viola John Koen Cello Intermission Brahms Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25 I. Allegro II. Intermezzo: Allegro ma non troppo III. Andante con moto IV. Rondo alla zingarese: Presto Cynthia Raim Piano (Guest) Paul Arnold Violin Kerri Ryan Viola Yumi Kendall Cello This program runs approximately 2 hours. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and also those who enjoy the a strong partnership with The Philadelphia Orchestra’s other area the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Orchestra has cultivated performances at the Mann Festival. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Eugene Ormandy Commercial Sound Recordings Ms

Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Ms. Coll. 410 Last updated on October 31, 2018. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2018 October 31 Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Summary Information Repository University of Pennsylvania: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts Creator Ormandy, Eugene, 1899-1985 -

The Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra 2019–20 Season The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the world’s preeminent orchestras. It strives to share the transformative power of music with the widest possible audience, and to create joy, connection, and excitement through music in the Philadelphia region, across the country, and around the world. Through innovative programming, robust educational initiatives, and commitment to the community, the ensemble is on a path to create an expansive future for classical music, and to further the place of the arts in an open and democratic society. Artistic Leadership Yannick Nézet-Séguin is now in his eighth season as the eighth music director of The Philadelphia Orchestra. He joins a remarkable list of music directors spanning the Orchestra’s 119 seasons: Fritz Scheel, Carl Pohlig, Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormandy, Riccardo Muti, Wolfgang Sawallisch, and Christoph Eschenbach. Under this superb guidance The Philadelphia Orchestra has represented an unwavering standard of excellence in the world of classical music—and it continues to do so today. Yannick’s connection to the musicians of the Orchestra has been praised by both concertgoers and critics, and he is embraced by the musicians of the Orchestra, audiences, and the community. Your Philadelphia Orchestra Your Philadelphia Orchestra takes great pride in its hometown, performing for the people of Philadelphia year-round, from Verizon Hall to community centers, classrooms to hospitals, and over the airwaves and online. The Orchestra continues to discover new and inventive ways to nurture its relationship with loyal patrons. The Kimmel Center, for which the Orchestra serves as the founding resident company, has been the ensemble’s home since 2001. -

N E W S R E L E a S E

N E W S R E L E A S E CONTACT: Katherine Blodgett phone : 215.893.1939 e-mail: [email protected] Jesson Geipel phone: 215.893.3136 e-mai l: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: April 18, 2013 Three Young Virtuosos Named Winners of the 2013 Philadelphia Orchestra Albert M. Greenfield Student Competition Exceptional Young Musicians in Greater Philadelphia Region Win Solo Opportunities to perform with The Philadelphia Orchestra (Philadelphia , April 18, 2013)–Three young artists have won the 2013 Philadelphia Orchestra Albert M. Greenfield Student Competition and will appear with the Orchestra as soloists over the next year. Thirteen students performed during the final round of competition on March 26 before an audience in Perelman Theater at The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. The winners of the 2013 Greenfield Competition are Audrey Emata (flute, from Wallingford, PA) in the Children’s Division, Zeyu Victor Li (violin, from Philadelphia, PA) in the Junior Division, and Won Suk Lee (percussion, performing on marimba, from Philadelphia, PA) in the Senior Division. All winners receive monetary awards in addition to their solo engagements with the Orchestra. New this year, five young musicians received honorable mentions: April Lee (cello) in the Children’s Division, Sein An (violin) and Hyun Jae Lim (violin) in the Junior Division, and Lauren Frey (soprano) and Jeonghyoun Lee (cello) in the Senior Division. During the Competition finals, the winners performed such works as Franz Doppler’s Fantaisie pastorale hongroise, Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, and Keiko Abe’s Prism Rhapsody for marimba and orchestra. “It is always so inspiring to witness the passion and talent these students possess, and gratifying to have a way to reward them for their dedication and determination,” said Philadelphia Orchestra President and CEO Allison Vulgamore. -

The Inaugural Season 23 Season 2012-2013

January 2013 The Inaugural Season 23 Season 2012-2013 Thursday, January 24, at 8:00 Friday, January 25, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Wagner Siegfried Idyll Intermission Bruckner Symphony No. 7 in E major I. Allegro moderato II. Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam— Moderato—Tempo I—Moderato—Tempo I III. Scherzo: Sehr schnell—Trio: Etwas langsamer—Scherzo da capo IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht schnell This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. 3 Story Title 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and also those who enjoy the a strong partnership with The Philadelphia Orchestra’s other area the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Orchestra has cultivated performances at the Mann Festival. an extraordinary history of Center, Penn’s Landing, artistic leaders in its 112 and other venues. The The ensemble maintains seasons, including music Philadelphia Orchestra an important Philadelphia directors Fritz Scheel, Carl Association also continues tradition of presenting Pohlig, Leopold Stokowski, to own the Academy of educational programs for Eugene Ormandy, Riccardo Music—a National Historic students of all ages. -

Season 2012-2013

Conductor Jaap van Zweden has regrettably withdrawn from the April 4-6 performances due to family reasons. This Thursday, April 4, and Friday, April 5, Philadelphia Orchestra Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin will conduct. On Saturday, April 6, Associate Conductor Cristian Măcelaru will lead the ensemble in his Philadelphia Orchestra subscription debut. As a result, the repertoire has been changed slightly. Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1 and Strauss’s Suite from Der Rosenkavalier will remain on the program, while Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night will be replaced by Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration. Season 2012-2013 Thursday, April 4, at 8:00 Friday, April 5, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, April 6, at 8:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor (April 4 and 5) Cristian Măcelaru Conductor (April 6) Garrick Ohlsson Piano Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 15 I. Maestoso II. Adagio III. Rondo: Allegro non troppo Intermission Strauss Death and Transfiguration, Op. 24 Strauss Suite from Der Rosenkavalier, Op. 59 This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 2 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 224 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive Philadelphia is home and Carnegie Hall and the sound, beloved for its the Orchestra nurtures Kennedy Center while also keen ability to capture the an important relationship enjoying a three-week hearts and imaginations not only with patrons who residency in Saratoga of audiences, and admired support the main season Springs, N.Y., and a strong for an unrivaled legacy of at the Kimmel Center but partnership with the Bravo! “firsts” in music-making, also those who enjoy the Vail festival. -

Members of the BUDAPEST STRING QUARTET EUGENE ISTOMIN, Pianist

1962 Eighty-fourth Season 1963 UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor First Concert Complete Series 3377 Twenty-third Chamber Music Festival Members of THE BUDAPEST STRING QUARTET ALEXANDER SCHNEIDER, Violin BORIS KROYT, Viola MISCHA SCHNEIDER, Violoncello with EUGENE ISTOMIN, Pianist WEDNESDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 20, 1963, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN FIRST PROGRAM Piano Quartet in E-flat major, K. 493 MOZART Allegro Larghetto Allegretto Piano Trio No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 11 BEETHOVEN Allegro con brio Adagio Tema con variazioni INTERMISSION Piano Quartet in G minor, Op. 25, No.1 BRAHMS Allegro Intermezzo: allegro, rna non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alIa Zingarese : presto Remaining F estivai Programs: Thursday: Piano Quartet K. 478 (Mozart); Piano Trio, Op. 1, No. 2 (Beethoven); Piano Trio, Op. 87 (Brahms). Friday: Piano Quartet, Op. 16 (Beethoven); Piano Trio, Op. 49 (Mendelssohn); Piano Quartet, Op. 26 (Brahms). Saturday: Prelude & Fugue, F minor (Bach- Mozart); Divertimento for String Trio K. 563 (Mozart); Serenade, Op. 8 (Beethoven). Sunday: Prelude & Fugue, D minor (Bach- Mozart); String Trio Op . 77B (Reger); String Trio, Op. 9, No.3 (Beethoven). Colttmbia R ecords Steinway Piano A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS 1962 - UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY PRESENTATIONS - 1963 All presentations are at 8:30 P.M. unless otherwise noted. HILL AUDITORIUM TORONTO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Tuesday, March 12 WALTER SUSSKIND, Conductor; ANNIE FISCHER, Pianist Program: Overture to "Leonore," No.3 BEETHOVEN Triptych .. MERCURE Piano Concerto No. 3 BARTOX Symphony No.4 in G major, Op. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 85, 1965-1966, Subscription

^< Mrs. Aaron Richmond and Walter Pierce ^^^ announce the 1966-67 Boston University O CELEBRITY SERIES Symphony Hall • Jordan Hall • Savoy Theatre SUBSCRIPTIONS NOW: 535 BOYLSTON ST. (SSfi#£) MAIL APPLICATIONS FILLED Detailed announcement upon request. (Tel. KE 6-6037) 7-EVENT SELECTIVE SERIES: $31.50 • $24.50 • $21.00 • $17.50 Select any 7 of the 32 events listed below: ROYAL HIGHLAND FUSILIERS (Boston Garden) Sun. Aft, Oct. 2 (Regimental Band, Massed Pipers, Drums from famous British Regiment, with crack military drill team) OBERNKIRCHEN CHILDREN'S CHOIR (The Happy Wanderers) Sun. Aft, Oct. 2 CARLOS MONTOYA, Flamenco Guitarist Sat Eve., Oct. » EUGENE ISTOMIN -ISAAC STERN - LEONARD ROSE TRIO Sun. Aft, Oct 9 MOSCOW CHAMBER ORCHESTRA, Rudolf Barshai, Cond Sun. Aft, Oct. 16 ROSALYN TURECK, Famous Pianist Fri. Eve., Oct. 21 DETROIT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Sun. Aft, Oct. 23 Sixten Ehrling, Cond., Malcolm Frager, Piano Soloist MUSIC FROM MARLBORO I Sun. Aft, Oct. 30 (Artists include: Lilian Kallir, pianist; Sylvia Rosenberg, violinist; Samuel Rhodes, viola; Mischa Schneider, cellist) D'OYLY CARTE OPERA COMPANY (Gilbert and Sullivan repertory) Tue. Eve., Nov. 1 EMIL GILELS, Soviet Pianist Fri. Eve., Nov. 4 JULIAN BREAM, British Guitarist-Lutenist Fri. Eve., Nov. 11 CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Jean Martinon, Cond. Sun. Aft, Nov. 13 JUILLIARD STRING QUARTET Sun. Aft, Nov. 20 MARTHA GRAHAM DANCE COMPANY Fri. Eve., Nov. 25 ZINO FRANCESCATTI -ROBERT CASADESUS Sun. Aft, Nov. 27 Famous French Violinist and Pianist RUDOLF SERKIN, Pianist Sun. Aft, Dec. 4 ALFRED BRENDEL, Brilliant Pianist Sun. Aft, Dec. 11 UKRAINIAN DANCE COMPANY Sun. Aft, Jan. 15 Company of 120 Folk Dancers from Soviet Union BRISTOL OLD VIC (Shakespeare Repertory) Tue.