Season 2012-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH to CO

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 7, 2018 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5700; [email protected] CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH TO CONDUCT THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC MOZART’s Piano Concerto No. 22 with TILL FELLNER in His Philharmonic Debut BRUCKNER’s Symphony No. 9 April 19, 21, and 24, 2018 Christoph Eschenbach will conduct the New York Philharmonic in a program of works by Austrian composers: Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 22, with Austrian pianist Till Fellner as soloist in his Philharmonic debut, and Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 (Ed. Nowak), Thursday, April 19, 2018, at 7:30 p.m.; Saturday, April 21 at 8:00 p.m.; and Tuesday, April 24 at 7:30 p.m. German conductor Christoph Eschenbach began his career as a pianist, making his New York Philharmonic debut as piano soloist in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in 1974. Both Christoph Eschenbach and Till Fellner won the Clara Haskil International Piano Competition, in 1965 and 1993, respectively. Mr. Fellner subsequently recorded Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 22 on the Claves label in collaboration with the Clara Haskil Competition. The New York Times wrote of Mr. Eschenbach’s conducting Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 with the New York Philharmonic in 2008: “Mr. Eschenbach, a compelling Bruckner interpreter, brought a sense of structure and proportion to the music without diminishing the qualities of humility and awe that make it so gripping. … the orchestra responded with playing of striking power and commitment.” Artists Christoph Eschenbach is in demand as a distinguished guest conductor with the finest orchestras and opera houses throughout the world, including those in Vienna, Berlin, Paris, London, New York, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Milan, Rome, Munich, Dresden, Leipzig, Madrid, Tokyo, and Shanghai. -

100Th Season Anniversary Celebration Gala Program At

Friday Evening, May 5, 2000, at 7:30 Peoples’ Symphony Concerts 100th Season Celebration Gala This concert is dedicated with gratitude and affection to the many artists whose generosity and music-making has made PSC possible for its first 100 years ANTON WEBERN (1883-1945) Langsaner Satz for String Quartet (1905) Langsam, mit bewegtem Ausdruck HUGO WOLF (1860-1903) “Italian Serenade” in G Major for String Quartet (1892) Tokyo String Quartet Mikhail Kopelman, violin; Kikuei Ikeda, violin; Kazuhide Isomura, viola; Clive Greensmith, cello LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Trio for piano, violin and cello in B-flat Major Op. 11 (1798) Allegro con brio Adagio Allegretto con variazione The Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio Joseph Kalichstein, piano; Jamie Laredo, Violin; Sharon Robinson. cello GYORGY KURTAG (b. 1926) Officium breve in memoriam Andreae Szervánsky 1 Largo 2 Piú andante 3 Sostenuto, quasi giusto 4 Grave, moto sostenuto 5 Presto 6 Molto agitato 7 Sehr fliessend 8 Lento 9 Largo 10 Sehr fliessend 10a A Tempt 11 Sostenuto 12 Sostenuto, quasi guisto 13 Sostenuto, con slancio 14 Disperato, vivo 15 Larghetto Juilliard String Quartet Joel Smirnoff, violin; Ronald Copes, violin; Samuel Rhodes, viola; Joel Krosnick, cello GEORGE GERSHWIN (1898-1937) arr. PETER STOLTZMAN Porgy and Bess Suite (1935) It Ain’t Necessarily So Prayer Summertime Richard Stoltzman, clarinet and Peter Stoltzman, piano intermission MICHAEL DAUGHERTY (b. 1954) Used Car Salesman (2000) Ethos Percussion Group Trey Files, Eric Phinney, Michael Sgouros, Yousif Sheronick New York Premiere Commissined by Hancher Auditorium/The University of Iowa LEOS JANÁCEK (1854-1928) Mládi (Youth) Suite for Wind Instruments (1924) Allegro Andante sostenuto Vivace Allegro animato Musicians from Marlboro Tanya Dusevic Witek, flute; Rudolph Vrbsky, oboe; Anthony McGill, clarinet; Jo-Ann Sternberg, bass clarinet; Daniel Matsukawa, bassoon; David Jolley, horn ZOLTAN KODALY (1882-1967) String Quartet #2 in D minor, Op. -

Rudolf Buchbinder, Piano

Cal Performances Presents Sunday, September 21, 2008, 3pm Hertz Hall Rudolf Buchbinder, piano PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Piano Sonata No. 3 in C major, Op. 2, No. 3 (1795) Allegro con brio Adagio Scherzo: Allegro Allegro assai Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 22 in F major, Op. 54 (1804) In tempo d’un Menuetto Allegretto INTERMISSION Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 24 in F-sharp major, Op. 78 (1809) Adagio cantabile — Allegro ma non troppo Allegro vivace Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 25 in G major, Op. 79 (1809) Presto alla tedesca Andante Vivace Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 28 in A major, Op. 101 (1816) Allegretto, ma non troppo Vivace alla marcia Adagio, ma non troppo, con affetto — Tempo del primo pezzo — Allegro This performance is made possible, in part, through the generosity of The Hon. Kathryn Walt Hall and Craig Hall. Cal Performances’ 2008–2009 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 25 About the Artist About the Artist performed Diabelli Variations collection written by Mozart and Beethoven. Mr. Buchbinder will visit Mr. Buchbinder attaches considerable impor- 50 Austrian composers. His 18-disc set of Haydn’s Munich several times throughout the season, per- tance to the meticulous study of musical sources. works earned him the Grand Prix du Disque, and forming the complete cycle of Beethoven sona- He owns more than 18 complete editions of his cycle of Mozart’s complete piano concertos with tas at the Prinzregententheater. In October and Beethoven’s sonatas and has an extensive collec- the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, recorded live at November, he will tour the United States with the tion of autograph scores, first editions and original the Vienna Konzerthaus, was chosen by Joachim Dresden Staatskapelle under Luisi, performing at documents. -

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

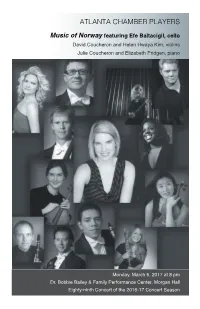

Atlanta Chamber Players, "Music of Norway"

ATLANTA CHAMBER PLAYERS Music of Norway featuring Efe Baltacigil, cello David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins Julie Coucheron and Elizabeth Pridgen, piano Monday, March 6, 2017 at 8 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Eighty-ninth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program JOHAN HALVORSEN (1864-1935) Concert Caprice on Norwegian Melodies David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) Andante con moto in C minor for Piano Trio David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello Julie Coucheron, piano EDVARD GRIEG Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45 Allegro molto ed appassionato Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza Allegro animato - Prestissimo David Coucheron, violin Julie Coucheron, piano INTERMISSION JOHAN HALVORSEN Passacaglia for Violin and Cello (after Handel) David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello EDVARD GRIEG Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36 Allegro agitato Andante molto tranquillo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello Elizabeth Pridgen, piano featured musician FE BALTACIGIL, Principal Cello of the Seattle Symphony since 2011, was previously Associate Principal Cello of The Philadelphia Orchestra. EThis season highlights include Brahms' Double Concerto with the Oslo Radio Symphony and Vivaldi's Double Concerto with the Seattle Symphony. Recent highlights include his Berlin Philharmonic debut under Sir Simon Rattle, performing Bottesini’s Duo Concertante with his brother Fora; performances of Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme with the Bilkent & Seattle Symphonies; and Brahms’ Double Concerto with violinist Juliette Kang and the Curtis Symphony Orchestra. Baltacıgil performed a Brahms' Sextet with Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Yo-Yo Ma, Pinchas Zukerman and Jessica Thompson at Carnegie Hall, and has participated in Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project. -

With a Rich History Steeped in Tradition, the Courage to Stand Apart and An

With a rich history steeped in tradition, the courage to stand apart and an enduring joy of discovery, the Wiener Symphoniker are the beating heart of the metropolis of classical music, Vienna. For 120 years, the orchestra has shaped the special sound of its native city, forging a link between past, present and future like no other. In Andrés Orozco-Estrada - for several years now an adopted Viennese - the orchestra has found a Chief Conductor to lead this skilful ensemble forward from the 20-21 season onward, and at the same time revisit its musical roots. That the Wiener Symphoniker were formed in 1900 of all years is no coincidence. The fresh wind of Viennese Modernism swirled around this new orchestra, which confronted the challenges of the 20th century with confidence and vision. This initially included the assured command of the city's musical past: they were the first orchestra to present all of Beethoven's symphonies in the Austrian capital as one cycle. The humanist and forward-looking legacy of Beethoven and Viennese Romanticism seems tailor-made for the Symphoniker, who are justly leaders in this repertoire to this day. That pioneering spirit, however, is also evident in the fact that within a very short time the Wiener Symphoniker rose to become one of the most important European orchestras for the premiering of new works. They have given the world premieres of many milestones of music history, such as Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony, Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-Lieder, Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand and Franz Schmidt's The Book of the Seven Seals - concerts that opened a door onto completely new worlds of sound and made these accessible to the greater masses. -

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

Voyager's Gold Record

Voyager's Gold Record https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_Golden_Record #14 score, next page. YouTube (Perlman): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVzIfSsskM0 Each Voyager space probe carries a gold-plated audio-visual disc in the event that the spacecraft is ever found by intelligent life forms from other planetary systems.[83] The disc carries photos of the Earth and its lifeforms, a range of scientific information, spoken greetings from people such as the Secretary- General of the United Nations and the President of the United States and a medley, "Sounds of Earth," that includes the sounds of whales, a baby crying, waves breaking on a shore, and a collection of music, including works by Mozart, Blind Willie Johnson, Chuck Berry, and Valya Balkanska. Other Eastern and Western classics are included, as well as various performances of indigenous music from around the world. The record also contains greetings in 55 different languages.[84] Track listing The track listing is as it appears on the 2017 reissue by ozmarecords. No. Title Length "Greeting from Kurt Waldheim, Secretary-General of the United Nations" (by Various 1. 0:44 Artists) 2. "Greetings in 55 Languages" (by Various Artists) 3:46 3. "United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs" (by Various Artists) 4:04 4. "The Sounds of Earth" (by Various Artists) 12:19 "Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047: I. Allegro (Johann Sebastian 5. 4:44 Bach)" (by Munich Bach Orchestra/Karl Richter) "Ketawang: Puspåwårnå (Kinds of Flowers)" (by Pura Paku Alaman Palace 6. 4:47 Orchestra/K.R.T. Wasitodipuro) 7. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 116, 1996-1997

SEIJI OZAWA- MUSIC DIRECTOR »-^uLUlSm*L. 1996-97 SEASON lIMNMSi '"•' Si"* *«£* 1 . >* -^ I j . *• r * The security of a trust, Fidelity service and expertise. A CLkwic Composition - A conductor and his orchestra — together, they perform masterpieces. Fidelity Now Fidelity Personal Trust Services Pergonal can help you achieve the same harmony for your trust portfolio of Trudt $400,000 or more. Serviced You'll receive superior trust services through a dedicated trust officer, with the added benefit of Fidelity's renowned money management expertise. And because Fidelity is the largest privately owned financial services firm in the nation, you Can rest assured that we will be there for the long term. Call JS*^ Fidelity Pergonal Trust Serviced at 1-800-854-2829. You'll applaud our efforts. Trust Services offered by Fidelity Management Trust Company For more information, visit a Fidelity Investor Center near you: Boston - Back Bay • Boston - Financial District • Braintree, MA • Burlington, MA Fidelity Investments' 17598.001 This should not be considered an offer to provide trust services in every state. Trust services vary by state. To determine whether Fidelity may provide trust services in your state, please call Fidelity at 1-800-854-2829. Investor Centers are branches of Fidelity Brokerage Services, Inc. Member NYSE, SIPC. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Sixteenth Season, 1996-97 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. R. Willis Leith, Jr., Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. -

Regulations & Programme 2021

XXIXe CONCOURS INTERNATIONAL DE PIANO CLARA HASKIL 27.08.-03.09.2021 VEVEY (SWITZERLAND) REGULATIONS & PROGRAMME 2021 REGISTRATION CLOSES: WEDNESDAY 28 APRIL 2021 1 RegulationsFONDATION SI BÉMOL and programme, April 2020, Concours International de Piano Clara Haskil CLARA HASKIL PRIZE WINNERS 1963 No prize awarded 1965 Christoph Eschenbach Germany 1967 Dinorah Varsi Uruguay 1969 No prize awarded 1971 No competition 1973 Richard Goode United States 1975 Michel Dalberto France 1977 Evgeni Koroliov USSR 1979 Cynthia Raim United States 1981 Konstanze Eickhorst Germany 1983 No prize awarded 1985 Nataša Veljković Yugoslavia 1987 Hiroko Sakagami Japan 1989 Gustavo Romero United States 1991 Steven Osborne Scotland 1993 Till Fellner Austria 1995 Mihaela Ursuleasa Romania 1997 Delphine Bardin France 1999 Finghin Collins Ireland 2001 Martin Helmchen Germany 2003 No prize awarded 2005 Sunwook Kim South Korea 2007 Hisako Kawamura Japan 2009 Adam Laloum France 2011 Cheng Zhang China 2013 Cristian Budu Brazil 2015 No prize awarded 2017 Mao Fujita Japan 2019 No prize awarded 2 Regulations and programme, April 2020, Concours International de Piano Clara Haskil I. GENERAL INFORMATION THE CLARA HASKIL COMPETITION The Competition’s purpose is to discover a young musician capable of representing the Competition’s va- lues: musicality, sensitivity, humility, constant re-evaluation, continual striving for excellence, attention to chamber music partners and respect for the composer’s musical text. These values are inspired by the life and career of Clara Haskil, a Swiss pianist born in Bucharest, Romania in 1895 and who died in Brussels in 1960. The programme reflects Clara Haskil’s vast repertoire through a recital, a chamber music performance and a concerto with orchestra. -

19Th September 2021

ZERMATT FESTIVAL ACADEMY 4 TH –19TH SEPTEMBER 2021 The village of Zermatt at the foot of the Matterhorn offers peace and relaxation in one of the most beautiful places in the world. This unique atmosphere, in the middle of a breath-taking natural landscape, enchanted Pablo Casals who regularly spent his summer holidays here in the 1950s and 60s. Together with Franz Seiler, General Manager of the Seiler Hotels Zermatt at that time, Casals founded the Zermatt summer concerts and master classes, to which he invited almost all of the famous musicians of his day as chamber music partners and teachers. This tradition in Zermatt was revived in 2005 with the creation of the Zermatt Music Festival. Chamber music and orchestral concerts are performed by the Scharoun Ensemble and other soloists of the Berliner Philharmoniker in the beautiful Riffelalp Kapelle located at 2’222 meters above sea level, as well as at other locations in Zermatt. Each year, highly gifted students are invited to take part in the Zermatt Festival Academy where they take lessons with members of the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin and perform alongside them in the Zermatt Festival Orchestra. Working intensively with these members of the Berliner Philharmoniker provides a unique educational experience at the highest possible level. After successfully participating in their first year of the academy, students have the opportunity to return for a second edition. By renewing this experience, they can continue to build on what they learnt the previous year. This year, Zermatt Festival Academy 2021 students will have the opportunity to perform in the run-up to the Zermatt Festival by accompanying the finalists of the Clara Haskil Piano Competition under the direction of Stanley Dodds in Vevey (1st–4th September 2021). -

Schoo} Ofmusic

I I \ SHEPHERD SCHOOL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA I LARRY RACHLEFF, music director SUSAN LORETTE DUNN, soprano STEPHEN KING, baritone Friday, April 2C 2007 8:00 p.rn. Stude Concert Hall RICE UNNERSITY Schoo}~~ ofMusic I PROGRAM Divertissement Jacques Ibert Introduction. Allegro vivo (1890-1962) Cortege. Moderato molto Nocturne. Lento Valse. Animato assai Parade. Tempo di marcia Finale. Quasi cadenza. Vivo. Tempo di galop Cristian Macelaru, conductor ) Don Quichotte a Dulcinee Maurice Ravel (Trios poemes de Paul Morand) (1875-1937) Chanson romanesque (Moderato) Chanson epique (Molto moderato) Chanson a boire (Allegro) Stephen King, soloist Cinq melodies populaires grecques Maurice Ravel / ( orchestrated by Maurice Ravel and Manuel Rosenthal) Le reveil de la mariee (Moderato mo/to) La-bas, vers l'eglise (Andante) Que! galant m'est comparable (Allegro) Chanson des cueilleuses de lentisques (Lento) Tout gai! (Allegro) Susan Lorette Dunn, soloist / INTERMISSION Symphony No. 103 in E-flat Major, Franz Joseph Haydn "Drum Roll" (1732-1809) Adagio - Allegro con spirito - Adagio Andante piu tosto Allegretto Menuet Allegro con spirito I The reverberative acoustics of Stude Concert Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Violin I Double Bass (cont.) Horn (cont.) J Freivogel, Evan Ha/loin Juliann Welch concertmaster Edward Merritt Amanda Chamberlain Trumpet Ying Fu Flute Greg Haro Kaoru Suzuki Hilary