Season 2012-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

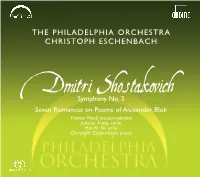

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

Connecting Analysis and Performance: a Case Study for Developing an Effective Approach

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 8 October 2013 Connecting Analysis and Performance: A Case Study for Developing an Effective Approach Annie Yih University of California, Santa Barbara Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Yih, Annie (2013) "Connecting Analysis and Performance: A Case Study for Developing an Effective Approach," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol6/iss1/8 This A Music-Theoretical Matrix: Essays in Honor of Allen Forte (Part IV), edited by David Carson Berry is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. CONNECTING ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE: A CASE STUDY FOR DEVELOPING AN EFFECTIVE APPROACH ANNIE YIH ne of the purposes of teaching music theory is to connect the practice of analysis with O performance. However, several studies have expressed concern over a lack of connec- tion between the two, and they have raised questions concerning the performative qualities of traditional analytic theory.1 If theorists are to achieve one of the objectives of analysis in provid- ing performers with information for making decisions, and to develop what John Rink calls “informed intuition,” then they need to understand what types of analysis—and what details in an analysis—can be of service to performers.2 As we know, notation is not music; notation must be realized as music, and the first step involves score study. -

Season 2012-2013

27 Season 2012-2013 Sunday, October 28, at 3:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra 28th Season of Chamber Music Concerts—Perelman Theater Mozart Duo No. 1 in G major, K. 423, for violin and viola I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Rondo: Allegro William Polk Violin Marvin Moon Viola Dvorˇák String Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 97 I. Allegro non tanto II. Allegro vivo III. Larghetto IV. Finale: Allegro giusto Kimberly Fisher Violin William Polk Violin Marvin Moon Viola Choong-Jin Chang Viola John Koen Cello Intermission Brahms Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25 I. Allegro II. Intermezzo: Allegro ma non troppo III. Andante con moto IV. Rondo alla zingarese: Presto Cynthia Raim Piano (Guest) Paul Arnold Violin Kerri Ryan Viola Yumi Kendall Cello This program runs approximately 2 hours. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and also those who enjoy the a strong partnership with The Philadelphia Orchestra’s other area the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Orchestra has cultivated performances at the Mann Festival. -

Overture November December 2018 2018 9/19/18 2:09 PM Page 1

NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2018 TURANGALÎLA-SYMPHONIE MARIN ALSOP AND THE BSO TAKE ON ONE OF THE 20TH CENTURY’S MOST MONUMENTAL SYMPHONIC WORKS MARIN ALSOP AND THE BSO NEW PROGRAM WIN OPUS KLASSIK FOR MAKES FREE TICKETS BERNSTEIN RECORDING AVAILABLE TO CHILDREN 15568-ad in Overture November December 2018_2018 9/19/18 2:09 PM Page 1 YULETIDE AT WINTERTHUR Open for holiday tours • November 17, 2018–January 6, 2019 Don’t miss this spectacular holiday showcase featuring tours of Henry Francis du Pont’s magnificent mansion decorated for Yuletide! Enjoy dining, shopping, musical and theatrical performances, and a full season of festive celebrations. Tickets at 800.448.3883 or visit winterthur.org/yuletide. Included with admission. Members free. Open New Year’s Day. Closed Thanksgiving and Christmas Day. Presented by r e i n r u o F n e B Winterthur is nestled in Delaware’s beautiful Brandywine Valley on Route 52, just minutes from I-95, Exit 7. 15568-ad in Overture November December 2018_2018 9/19/18 2:09 PM Page 1 NOVEMBER/ CONTENTS DECEMBER 2018 2 From the President 4 In Tempo: News of Note 6 BSO Live: Calendar of Events 7 Orchestra Roster 8 Turangalîla-symphonie Marin Alsop and the BSO take on one of the 20th century’s most monumental symphonic works 10 Poulenc Concerto for Two Pianos NOV 9–11 16 Copland Symphony No. 3 YULETIDE AT WINTERTHUR NOV 15 & 18 Off The Cuff: Copland Open for holiday tours • November 17, 2018–January 6, 2019 Symphony No. 3 Don’t miss this spectacular holiday showcase featuring tours of Henry Francis du Pont’s NOV 16 & 17 magnificent mansion decorated for Yuletide! Enjoy dining, shopping, musical and theatrical 20 Violinist Joshua Bell performances, and a full season of festive celebrations. -

The Chopin Foundation of the United States Presents Prizewinner of the Second American National Chopin Competition

RICE UNIVERSITY The Chopin Foundation of the United States presents ELlER SUAREZ, piano Prizewinner of the Second American National Chopin Competition Sunday, March 30, 1980 SSM 8:00p.m. in Hamman Hall 81 ._.30 iW~ PROGRA M -Oiapm eci1a1 - --..:.....;: - ._ Four Etudes: in .C-sharp minor, Dp. 2,5, No. 7 in A-flat, Op. _10, No. 10 in G-flat, GJp, lO, No. 5 in B-minor, Op. 25, No. 10 Nocturne in E-jlal Major, Op. 55, No. 2 Pownaise in F-sharp Minor, Op. 44 Interm ission Four Mazurkas, Op. 41 Sonata in B-f/a t Mi1zor, Op. 35 Grave .Scherzo Marche Funebre Finale: Presto Photographing and sound recording are prohibited. We further regret that audible paging devices not be used during performance. Paging armngtmJents may be made with ushers. ELlER SUAREZ was born in 1952 in Havana, Cubo. He received his Bachelor of Music from the University of Miami under full scholarship, and his Master of Music from The Juilliard School under Honorary Scholarship. He has studied with Eva Suarez, Claudina Mendez, Sergei Tamowsky, George Roth, Ivan Davis and Adele Marcus. Mr. Suarez has performed with both the Miami Beach Symphony and tile Miami Symphonic Society Orchestra, as well as the Dallas Symphony and ihe Florida Philharmonic. Currently, Mr. Suarez is a teaching assistant to Adele Marcus at The Juilliard School. THE INTERNATIONAL CHOPIN COMPETITION The first F. Chopin International Piano Competition was held in Jammry, 1927, at the hall of the Warsaw Philharmonic. The Jury consisted of a dozen eminent Polish pianists and pedagogues, and 17 of the 27 contestants were Polish. -

The Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra 2019–20 Season The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the world’s preeminent orchestras. It strives to share the transformative power of music with the widest possible audience, and to create joy, connection, and excitement through music in the Philadelphia region, across the country, and around the world. Through innovative programming, robust educational initiatives, and commitment to the community, the ensemble is on a path to create an expansive future for classical music, and to further the place of the arts in an open and democratic society. Artistic Leadership Yannick Nézet-Séguin is now in his eighth season as the eighth music director of The Philadelphia Orchestra. He joins a remarkable list of music directors spanning the Orchestra’s 119 seasons: Fritz Scheel, Carl Pohlig, Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormandy, Riccardo Muti, Wolfgang Sawallisch, and Christoph Eschenbach. Under this superb guidance The Philadelphia Orchestra has represented an unwavering standard of excellence in the world of classical music—and it continues to do so today. Yannick’s connection to the musicians of the Orchestra has been praised by both concertgoers and critics, and he is embraced by the musicians of the Orchestra, audiences, and the community. Your Philadelphia Orchestra Your Philadelphia Orchestra takes great pride in its hometown, performing for the people of Philadelphia year-round, from Verizon Hall to community centers, classrooms to hospitals, and over the airwaves and online. The Orchestra continues to discover new and inventive ways to nurture its relationship with loyal patrons. The Kimmel Center, for which the Orchestra serves as the founding resident company, has been the ensemble’s home since 2001. -

A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential Actf Ors in Performer Repertoire Choices

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 2020 A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential actF ors in Performer Repertoire Choices Yuan-Hung Lin Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Lin, Yuan-Hung, "A Study of Select World-Federated International Piano Competitions: Influential actF ors in Performer Repertoire Choices" (2020). Dissertations. 1799. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1799 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF SELECT WORLD-FEDERATED INTERNATIONAL PIANO COMPETITIONS: INFLUENTIAL FACTORS IN PERFORMER REPERTOIRE CHOICES by Yuan-Hung Lin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. Elizabeth Moak, Committee Chair Dr. Ellen Elder Dr. Michael Bunchman Dr. Edward Hafer Dr. Joseph Brumbeloe August 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Yuan-Hung Lin 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT In the last ninety years, international music competitions have increased steadily. According to the 2011 Yearbook of the World Federation of International Music Competitions (WFIMC)—founded in 1957—there were only thirteen world-federated international competitions at its founding, with at least nine competitions featuring or including piano. One of the founding competitions, the Chopin competition held in Warsaw, dates back to 1927. -

The Inaugural Season 23 Season 2012-2013

January 2013 The Inaugural Season 23 Season 2012-2013 Thursday, January 24, at 8:00 Friday, January 25, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Wagner Siegfried Idyll Intermission Bruckner Symphony No. 7 in E major I. Allegro moderato II. Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam— Moderato—Tempo I—Moderato—Tempo I III. Scherzo: Sehr schnell—Trio: Etwas langsamer—Scherzo da capo IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht schnell This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. 3 Story Title 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and also those who enjoy the a strong partnership with The Philadelphia Orchestra’s other area the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Orchestra has cultivated performances at the Mann Festival. an extraordinary history of Center, Penn’s Landing, artistic leaders in its 112 and other venues. The The ensemble maintains seasons, including music Philadelphia Orchestra an important Philadelphia directors Fritz Scheel, Carl Association also continues tradition of presenting Pohlig, Leopold Stokowski, to own the Academy of educational programs for Eugene Ormandy, Riccardo Music—a National Historic students of all ages. -

Included Services: CHOPIN EXCLUSIVE TOUR / Tour CODE A

Included services: CHOPIN EXCLUSIVE TOUR / Tour CODE A-6 • accommodation at Sofitel Victoria, 5* hotel - Warsaw [4 nights including buffet breakfast] Guaranteed Date 2020 • transportation by deluxe motor coach (up to 49pax) or minibus (up to 19 pax) throughout all the tour • English speaking tour escort throughout all the tour Starting dates in Warsaw Ending dates in Warsaw • Welcome and farewell dinner (3 meals with water+ coffee/tea) Wednesday Sunday • Lunch in Restaurant Przepis na KOMPOT • local guide for a visits of Warsaw October 21 October 25 • Entrance fees: Chopin Museum, Wilanow Palace, POLIN Museum, Żelazowa Wola, Nieborow • Chopin concert in the Museum of Archdiocese • Chocolate tasting • Concert of Finalists of Frederic Chopin Piano Competition • Ballet performance or opera at the Warsaw Opera House Mazurkas Travel Exclusive CHOPIN GUARANTEED DEPARTURE TOUR OCTOBER 21-25 / 2020 Guaranteed Prices 2020 Price per person in twin/double room EUR 992 Single room supplement EUR 299 Mazurkas Travel T: + 48 22 536 46 00 ul. Wojska Polskiego 27 www.mazurkas.com.pl 01-515 Warszawa [email protected] October 21 / 2020 - Wednesday October 22 / 2015 - Thursday October 23 / 2020 - Friday October 24 / 2020 - Saturday WARSAW WARSAW WARSAW WARSAW-ZELAZOWA WOLA- WARSAW (Welcome dinner) (Breakfast) (Breakfast) (Breakfast, lunch & farEwell dinner) After arrival, you will be met and transferred to your hotel in See the Krasinski Palace with the Chopin Drawing Room Morning visit to one of the most splendid residence of Drive to Zelazowa Wola. This is where on February 22, 1810 the heart of the city. where Chopin performed his etudes, some polonaises, and Warsaw, the Wilanow Palace and Royal Gardens. -

A Better Kind of Bank Presenting the World’S finest Classical Artists Since 1919 2016|2017

A Better Kind of Bank Presenting the world’s finest classical artists since 1919 2016|2017 INTERNATIONAL SERIES AT THE GRANADA THEATRE American Riviera Bank is your community bank; owned by our employees, customers and local shareholders — people just like you. We know our customers and they know us. It’s a different kind of relationship. Daniil Rabovsky It’s better. Come visit a branch, you’ll feel the difference when you walk in the door. ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA NIKOLAY ALEXEEV Conductor Santa Barbara Montecito Goleta Online Mobile App GARRICK OHLSSON Piano TUESDAY, MARCH 14, 2017, 8PM The Granada Theatre AmericanRivieraBank.com | 805.965.5942 (Santa Barbara Center for the Performing Arts) COMMUNITY ARTS MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF SANTA BARBARA, INC “Cottage’s iMRI technology offered me a different path to treat my brain tumor.” Shortly after her procedure, Corby was back to hiking her favorite trail. Corby Santa Maria JESSIE ARMS BOTKE (1883-1971) WHITE PEACOCK IN MAGNOLIA TREE WATERCOLOR AND GOUACHE ON PAPER || 15” HIGH X 13” WIDE When doctors diagnosed Corby with a brain tumor they believed was difficult to treat, they STEWART recommended an intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging procedure (iMRI). The Santa FINE ART Barbara Neuroscience Institute at Cottage is one of just a handful of hospitals in the nation ESTABLISHED 1986 DIANE WARREN STEWART who offer this specialized medicine. Our advanced imaging system provides neurosurgeons with the clearest images during brain surgery, helping them remove the most difficult to treat tumors. iMRI technology provides some patients with a different path and helps reduce Specializing in early California Plein the likelihood of an additional procedure. -

April 03, 2018

April 03, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “We have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak.” — Epictetus Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Vivaldi Violin Concerto in E, Op. 3 No. 12 Academy of Ancient Music/Hogwood L'Oiseau-Lyre 414 554 028941455420 Awake! 00:11 Buy Now! Chopin Four Nocturnes, Opp. 48 & 55 Garrick Ohlsson Arabesque Z6653 026724665325 00:40 Buy Now! German Welsh Rhapsody Scottish National Orchestra/Gibson EMI 69206 077776920627 00:59 Buy Now! Adam Overture ~ If I Were King Dresden State Orchestra/Vonk Ars Vivendi 036 4101380000492 01:08 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 084 in E flat Amsterdam Baroque/Koopman Erato 45807 022924580727 Johannesen/Radio Luxembourg 01:33 Buy Now! Saint-Saëns Piano Concerto No. 4 in C minor, Op. 44 Vox 7201 04716372012 Orchestra/Kontarsky 02:00 Buy Now! Corelli Concerto Grosso in B flat, Op. 6 No. 5 Cantilena/Shepherd Chandos 8336/7/8 N/A Castelnuovo- 02:13 Buy Now! Guitar Quintet, Op. 143 Yamashita/Tokyo String Quartet RCA 60421 090266042128 Tedesco Harpsichord Concerto No. 1 in D minor, BWV 02:38 Buy Now! Bach Pinnock/English Concert Archiv 415 991 028941599124 1052 03:01 Buy Now! My Life in Music 04:00 Buy Now! Grieg Lyric Pieces No. 1, Op. 12 Eva Knardahl BIS 104 7318590001042 04:14 Buy Now! Haydn Horn Concerto No. 1 in D Koster/L'Archibudelli Sony 68253 074646825327 Variations on a Hungarian Folksong, "The 04:33 Buy Now! Kodaly Chicago Symphony/Jarvi Chandos 8877 095115887721 Peacock" 04:59 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Hebrides Overture, Op. -

2010 Program This Year Marks the 15Th Miyazaki International Music Festival

15h Miyazaki International Music Festival 2010 15th MIYAZAKI INTERNATIONAL MUSIC FESTIVAL Sat 24 April – Sun 9 May 2010 at Medikit Arts Center (Miyazaki Prefectural Arts Center) Isaac Stern Hall and other venues Sponsors: Miyazaki Prefecture, Miyazaki Prefectural Arts Center, Japan Center for Local Autonomy Co-sponsor: Miyazaki Prefectural Board of Education Celebrating the Romance of Spring with Brilliant Blossoms of Music 2010 Program This year marks the 15th Miyazaki International Music Festival. As part of this grand celebration, this year will feature the elegant sounds of the Philidelphia Orchestra conducted by Charles Dutoit, the Juilliard String Quartet – one of the world's top quartets, internationally renowned violinists Julian Rachlin and Pavel Vernikov, and chamber music by a host of top artists from Japan and around the world. Their music will celebrate the success of past music festivals and bring forth new brilliant blossoms of music. We hope you enjoy the spectacular sounds that bloom when the goddess of music once again comes to Miyazaki. UMK Classics April 25 (Sun) Doors open 4:00pm Concert 1 Charles Dutoit, Elegant Sounds of Philadelphia Concert begins 5:00pm Venue: Medikit Arts Center Isaac Stern Hall Stravinsky: Firebird (1910 Ballet Score) Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring Conductor: Charles Dutoit with The Philadelphia Orchestra ~The Mysterious Power of Music~ Brought to You by Miyazaki Bank April 28 (Wed) Concert 2 Isaac Stern Memorial Concert Doors open 6:00pm Venue: Medikit Arts Center Isaac Stern Hall Concert begins 7:00pm Mozart: Piano Quartet No.2 in E-flat major, K.493 Piano: Yukio Yokoyama Violin: Tsugio Tokunaga Viola: Sachiko Suda Cello: Nobuo Furukawa Brahms: String Sextet No.1 in B-flat major, Op.18 Violin: Nicholas Eanet, Ronaldo Copes Viola: Samuel Rhodes, Masao Kawasaki Cello: Noboru Kamimura, Nobuo Furukawa Celebrating its 70th anniversary, April 29 (Thu) Miyazaki Nichinichi Shimbun opens the musical gates.