Philadelphia Maestros: Ormandy, Muti, Sawallisch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

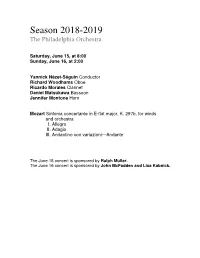

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

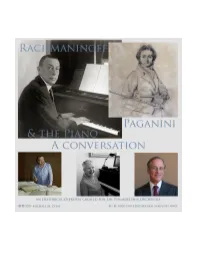

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation Tracks and clips 1. Rachmaninoff in Paris 16:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, Michael Rabin, EMI 724356799820, recorded 9/5/1958. b. Sergey Rachmaninoff (SR), Rapsodie sur un theme de Paganini, Op. 43, SR, Leopold Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (PO), BMG Classics 09026-61658, recorded 12/24/1934 (PR). c. Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (FC), Twelve Études, Op. 25, Alfred Cortot, Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG) 456751, recorded 7/1935. d. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, SR, Eugene Ormandy (EO), PO, Naxos 8.110601, recorded 12/4/1939.* e. Carl Maria von Weber, Rondo Brillante in E♭, J. 252, Julian Jabobson, Meridian CDE 84251, released 1993.† f. FC, Twelve Études, Op. 25, Ruth Slenczynska (RS), Musical Heritage Society MHS 3798, released 1978. g. SR, Preludes, Op. 32, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. h. Georges Enesco, Cello & Piano Sonata, Op. 26 No. 2, Alexandre Dmitriev, Alexandre Paley, Saphir Productions LVC1170, released 10/29/2012.† i. Claude Deubssy, Children’s Corner Suite, L. 113, Walter Gieseking, Dante 167, recorded 1937. j. Ibid., but SR, Victor B-24193, recorded 4/2/1921, TvJ35-zZa-I. ‡ k. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, Walter Gieseking, John Barbirolli, Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Music & Arts MACD 1095, recorded 2/1939.† l. SR, Preludes, Op. 23, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. 2. Rachmaninoff & Paganini 6:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, op. cit. b. PR. c. Arcangelo Corelli, Violin Sonata in d, Op. 5 No. 12, Pavlo Beznosiuk, Linn CKD 412, recorded 1/11/2012.♢ d. -

Program Notes | Yannick and Manny

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, November 29, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, November 30, at 8:00 Saturday, December 1, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Emanuel Ax Piano Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83 I. Allegro non troppo II. Allegro appassionato III. Andante—Più adagio—Tempo I IV. Allegretto grazioso—Un poco più presto Intermission Brown Perspectives United States premiere Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 I. Allegro maestoso II. Poco adagio III. Scherzo: Vivace IV. Finale: Allegro This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Elia D. Buck and Caroline B. Rogers. The November 29 concert is also sponsored by the Louis N. Cassett Foundation. The November 30 concert is sponsored by Alexandra Edsall and Robert Victor. The December 1 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us following the November 30 and December 1 concerts for a free Organ Postlude featuring Peter Richard Conte. Brahms Prelude, from Prelude and Fugue in G minor Brahms Fugue in A-flat minor Dvořák/transcr. Conte Humoresque, Op. 101, No. 7 Widor Toccata, from Organ Symphony No. 5 in F minor, Op. 42, No. 1 The Organ Postludes are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

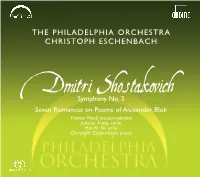

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

Festival of Strings 2017 Flier

Festival of Strings 2017 Five Consecutive days of Concerts and Master Classes with Internationally Recognized Artists and our own SHSU faculty Dylana Jenson (violin), The Solera String Quartet with Josu de Solaun (piano), The Kolonneh String Quartet (SHSU faculty) • Thursday, October 5, Concert Hall, 2:30-5:00 pm Master class with Dylana Jenson • Friday, October 6, Recital Hall 1:00-3:00 pm Master class with Dylana Jenson • Friday, October 6, Concert Hall, 7:30 pm SHSU Symphony Orchestra Concert with guest soloist Daniel Saenz (cello) VENUE CHANGE! • Saturday, October 7, Recital Hall, 7:30 pm University Heights Baptist Church Guest Artist Recital 2400 Sycamore Ave, Huntsville, TX 77340 Dylana Jenson, (violin) with Josu de Solaun (piano) •Sunday, October 8, Recital Hall, 3:30 pm Guest Artist Recital The Solera String Quartet with Josu de Solaun (piano) • Monday, October 9, Recital Hall, 7:30 pm The Kolonneh String Quartet www.shsu.edu/music/events Sam Houston State University Festival of Strings 2017 Guest Artists DYLANA JENSON Dylana Jenson has performed with most major orchestras in the United States and traveled to Europe, Australia, Japan and Latin America for concerts, recitals and recordings. After her triumphant success at the Tchaikovsky Competi- tion, where she became the youngest and first American woman to win the Silver Medal, she made her Carnegie Hall debut playing the Sibelius Concerto with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Following her most recent Carnegie Hall performance, Jenson again electrified both audience and critics in her per- formance of Karl Goldmark's violin concerto. According to Strad Magazine, "In Jenson's hands, even lyrical passages had an intense, tremulous quality.. -

N E W S R E L E A

N E W S R E L E A S E CONTACT: Katherine Blodgett Vice President of Public Relations and Communications Phone: 215.893.1939 E-mail: [email protected] Jesson Geipel Public Relations Manager FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Phone: 215.893.3136 DATE: October 18, 2012 E-mail: [email protected] YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN’S INAUGURAL SEASON AS MUSIC DIRECTOR OF THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA BEGINS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2012, WITH A GALA CONCERT FEATURING THE INCOMPARABLE RENÉE FLEMING Opening Weeks of Nézet-Séguin’s Tenure to Feature Verdi’s Requiem, His Carnegie Hall Debut, and Concerts with Violinist Joshua Bell (Philadelphia, October 18, 2012)—Yannick Nézet-Séguin officially begins his tenure as The Philadelphia Orchestra’s eighth music director with a gala Opening Concert on October 18, 2012, two weeks of subscription concerts at the Orchestra’s home in Verizon Hall at the Kimmel Center, and with his Carnegie Hall debut on October 23 in New York City. Nézet-Séguin was named music director designate of the legendary ensemble in 2010. The gala concert, featuring soprano Renée Fleming, includes Ravel’s Shéhérazade, Brahms’s Symphony No. 4, and “Mein Elemer!” from Arabella by Richard Strauss. For the Orchestra’s first subscription series at the Kimmel Center and for his Carnegie Hall debut, Nézet-Séguin has chosen Verdi’s Requiem, featuring soprano Marina Poplavskaya, mezzo-soprano Christine Rice, tenor Rolando Villazón, bass Mikhail Petrenko, and the Westminster Symphonic Choir. Philadelphia Orchestra Association President and CEO Allison Vulgamore said, “This is the launch of a new chapter for The Philadelphia Orchestra. We have been anticipating this moment for what seems a very long time, and the entire organization couldn’t be more thrilled that it is finally upon us. -

Mediation Is Provided by Our Management Staff

What We Do. By arrangement with Jack Price, Price Rubin & Partners has been a leader in the Artist Management, Concert Management, Music, Entertainment and Performing Arts Industries since 1984 providing direct marketing ser- vices to emerging and highly-credentialed classical, jazz, dance, cross-over, country, western, folk, new-age and film artists. Our roster includes some of the most-accomplished and awarded artists performing today. More than just traditional artist representation services, Premium Management delivers super-targeted direct marketing to concert presenters and performing arts organizations who engage performing artists. Our marketing staff makes approximately 3500-4000 calls each month to decision-makers who buy talent. Our clients receive highly-individ- ualized targeted marketing that focuses on branding and getting them much-needed considering from performing arts presenters who will be engaging artists in the future. When interest is expressed our managers take over the lead and work to establish a relationship between the presenter and artist. Contract mediation is provided by our management staff. We also offer various marketing services as well as patron marketing, public relations, adver- tising, fundraising, audience development, general artist management, PRPRadioOne and Price Rubin Music Television. Founder Jack Price. The indomitable Jack Price started Price Rubin & Partners in 1984 in response to his own career as an internationally renowned and celebrated concert pianist. Jack took on the role as manager -

THE KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION CHOPIN PIANO COMPETITION HISTORICAL OVERVIEW in 1949, to Mark the Centennial of the Death of Fryderyk

THE KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION CHOPIN PIANO COMPETITION HISTORICAL OVERVIEW In 1949, to mark the centennial of the death of Fryderyk Chopin, the Kosciuszko Foundation’s Board of Trustees authorized a National Committee to encourage observance of the anniversary through concerts and programs throughout the United States. Howard Hansen, then Director of the Eastman School of Music, headed this Committee, which included, among others, Claudio Arrau, Vladimir Horowitz, Serge Koussevitzky, Claire Booth Luce, Eugene Ormandy, Artur Rodzinski, George Szell, and Bruno Walter. The Chopin Centennial was inaugurated by Witold Malcuzynski at Carnegie Hall on February 14, 1949. A repeat performance was presented by Malcuzynski eight days later, on Chopin’s birthday, in the Kosciuszko Foundation Gallery. Abram Chasins, composer, pianist, and music director of the New York Times radio stations WQXR and WQWQ, presided at the evening and opened it with the following remarks: In seeking to do justice to the memory of a musical genius, nothing is so eloquent as a presentation of the works through which he enriched our musical heritage. … In his greatest work, Chopin stands alone … Throughout the chaos, the dissonance of the world, Chopin’s music has been for many of us a sanctuary … It is entirely fitting that this event should take place at the Kosciuszko Foundation House. This Foundation is the only institution which we have in America which promotes cultural relations between Poland and America on a non-political basis. It has helped to understand the debt which mankind owes to Poland’s men of genius. At the Chopin evening at the Foundation, two contributions were made. -

A Career Filled with High Notes

A Career Filled With High Notes Michael Tilson Thomas, now in the final season of his 25 years at the helm of the San Francisco Symphony, has left a profound imprint on both the orchestra and the city. By David Mermelstein March 3, 2020 Michael Tilson Thomas, music director of the San Francisco Symphony, in 2018 When Michael Tilson Thomas became music director of this city’s estimable but not very exciting or forward-looking symphony orchestra in 1995, he had been working in London and needed an American career boost, and the ensemble was looking for an energetic maestro who would elevate its profile and maybe even lend it “buzz.” A quarter-century later, their partnership stands as one of the great success stories in U.S. musical history, thanks in large part to Mr. Thomas’s searching intellect, fierce curiosity, and supreme repertorial fluency. His direct connection to musical history, unmatched in our time, hasn’t hurt, either. As a result, the 109-year-old San Francisco Symphony is now widely regarded as among this country’s finest orchestras—right up there with East Coast titans like the New York Philharmonic, the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra. West of Chicago, only the Los Angeles Philharmonic challenges San Francisco’s dominance. But nothing lasts forever, and Mr. Thomas, who turned 75 just before Christmas, is midway through his last season at the helm. Fittingly, the exit music, as it were, hearkens back to past triumphs. On Friday, Mr. Thomas and the orchestra will perform Mahler’s Symphony No. -

Elias String Quartet

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2013-2014 THE gERTRUDE cLARKE wHITTALL fOUNDATION IN THE LIBRARY oF CONGRESS eLIAS sTRING qUARTET Friday, March 7, 2014 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building In 1935 Gertrude Clarke Whittall gave the Library of Congress five Stradivari instruments and three years later built the Whittall Pavilion in which to house them. The GERTRUDE CLARKE WHITTALL FOUNDATION was established to provide for the maintenance of the instruments, to support concerts (especially those that feature her donated instruments), and to add to the collection of rare manuscripts that she had additionally given to the Library. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Friday, March 7, 2014 — 8 pm THE gERTRUDE cLARKE wHITTALL FOUNDATION In THE LIBRARY oF CONGRESS eLIAS sTRING QUARTET SARA BITLLOCH & DONALD GRANT, vIOLINS mARTIN sAVING, VIOLA mARIE bITLLOCH, CELLO • Program jOSEPH hAYDN (1732-1809) String Quartet in F major, op.