Salamander Mating Behaviors and Their Consequences for Individuals and Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004A IE Reports

Contents Introduction…………………………………….…………………………………1 Using GIS to predict plant distributions: a new approach (Amy Lorang)……………………………………………………………………...3 Impacts of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid on Canadian and Carolina Hemlock Forests (Josh Brown)………………………………………………..……………………19 Effects of Adelgid-Induced Decline in Hemlock Forests on Terrestrial Salamander Populations of the Southern Appalachians: A Preliminary Study (Shelley Rogers)………………………………………………………………….37 Riparian zone structure and function in Southern Appalachian forested headwater catchments (Katie Brown)…………………………………………………………………….60 Successional Dynamics of Dulany Bog (Michael Nichols)………………………………………………………………...77 Mowing and its Effect on the Wildflowers of Horse Cove Road on the Highlands Plateau ((Megan Mailloux)……………………………………………………………….97 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………..114 1 Introduction In the Fall of 2004, twelve undergraduate students from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill had the opportunity to complete ecological coursework through the Carolina Environmental Program’s Highlands field site. This program allows students to learn about the rich diversity of plants and animals in the southern Appalachians. The field site is located on the Highlands Plateau, North Carolina, near the junction of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. The plateau is surrounded by diverse natural areas which create an ideal setting to study different aspects of land use change and threats to biodiversity. The Highlands Plateau is a temperate rainforest of great biodiversity, a patchwork of rich forests, granite outcrops, and wet bogs. Many rare or interesting species can be found in the area, with some being endemic to a specific stream or mountaintop. Some of these are remnants of northern species that migrated south during the last ice age; others evolved to suit a particular habitat, with a slightly different species in each stream. -

The Salamanders of Tennessee

Salamanders of Tennessee: modified from Lisa Powers tnwildlife.org Follow links to Nongame The Salamanders of Tennessee Photo by John White Salamanders are the group of tailed, vertebrate animals that along with frogs and caecilians make up the class Amphibia. Salamanders are ectothermic (cold-blooded), have smooth glandular skin, lack claws and must have a moist environment in which to live. 1 Amphibian Declines Worldwide, over 200 amphibian species have experienced recent population declines. Scientists have reports of 32 species First discovered in 1967, the golden extinctions, toad, Bufo periglenes, was last seen mainly species of in 1987. frogs. Much attention has been given to the Anurans (frogs) in recent years, however salamander populations have been poorly monitored. Photo by Henk Wallays Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra terrestris 2 Why The Concern For Salamanders in Tennessee? Their key role and high densities in many forests The stability in their counts and populations Their vulnerability to air and water pollution Their sensitivity as a measure of change The threatened and endangered status of several species Their inherent beauty and appeal as a creature to study and conserve. *Possible Factors Influencing Declines Around the World Climate Change Habitat Modification Habitat Fragmentation Introduced Species UV-B Radiation Chemical Contaminants Disease Trade in Amphibians as Pets *Often declines are caused by a combination of factors and do not have a single cause. Major Causes for Declines in Tennessee Habitat Modification -The destruction of natural habitats is undoubtedly the biggest threat facing amphibians in Tennessee. Housing, shopping center, industrial and highway construction are all increasing throughout the state and consequently decreasing the amount of available habitat for amphibians. -

Amphibian and Reptile Checklist

KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS ___ Eastern Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) – BLUE RIDGE (NC‐C, VA‐C) Habitat: Varies from rocky timbered hillsides to flat farmland. The following codes refer to an animal’s abundance in ___ Eastern Hog‐nosed Snake (Heterodon platirhinos) – PARKWAY suitable habitat along the parkway, not the likelihood of (NC‐R, VA‐U) Habitat: Sandy or friable loam soil seeing it. Information on the abundance of each species habitats at lower elevation. AMPHIBIAN & comes from wildlife sightings reported by park staff and ___ Eastern Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) – (NC‐U, visitors, from other agencies, and from park research VA‐U) Habitat: Generalist at low elevations. reports. ___ Northern Mole Snake (Lampropeltis calligaster REPTILE C – COMMON rhombomaculata) – (VA‐R) Habitat: Mixed pine U – UNCOMMON forests and open fields under logs or boards. CHECKLIST R – RARE ___ Eastern Milk Snake (Lampropeltis triangulum) – (NC‐ U, VA‐U) Habitat: Woodlands, grassy balds, and * – LISTED – Any species federally or state listed as meadows. Endangered, Threatened, or of Special Concern. ___ Northern Water Snake (Nerodia sipedon sipedon) – (NC‐C, VA‐C) Habitat: Wetlands, streams, and lakes. Non‐native – species not historically present on the ___ Rough Green Snake (Opheodrys aestivus) – (NC‐R, parkway that have been introduced (usually by humans.) VA‐R) Habitat: Low elevation forests. ___ Smooth Green Snake (Opheodrys vernalis) – (VA‐R) NC – NORTH CAROLINA Habitat: Moist, open woodlands or herbaceous Blue Ridge Red Cope's Gray wetlands under fallen debris. Salamander Treefrog VA – VIRGINIA ___ Northern Pine Snake (Pituophis melanoleucus melanoleucus) – (VA‐R) Habitat: Abandoned fields If you see anything unusual while on the parkway, please and dry mountain ridges with sandier soils. -

Biodiversity from Caves and Other Subterranean Habitats of Georgia, USA

Kirk S. Zigler, Matthew L. Niemiller, Charles D.R. Stephen, Breanne N. Ayala, Marc A. Milne, Nicholas S. Gladstone, Annette S. Engel, John B. Jensen, Carlos D. Camp, James C. Ozier, and Alan Cressler. Biodiversity from caves and other subterranean habitats of Georgia, USA. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 82, no. 2, p. 125-167. DOI:10.4311/2019LSC0125 BIODIVERSITY FROM CAVES AND OTHER SUBTERRANEAN HABITATS OF GEORGIA, USA Kirk S. Zigler1C, Matthew L. Niemiller2, Charles D.R. Stephen3, Breanne N. Ayala1, Marc A. Milne4, Nicholas S. Gladstone5, Annette S. Engel6, John B. Jensen7, Carlos D. Camp8, James C. Ozier9, and Alan Cressler10 Abstract We provide an annotated checklist of species recorded from caves and other subterranean habitats in the state of Georgia, USA. We report 281 species (228 invertebrates and 53 vertebrates), including 51 troglobionts (cave-obligate species), from more than 150 sites (caves, springs, and wells). Endemism is high; of the troglobionts, 17 (33 % of those known from the state) are endemic to Georgia and seven (14 %) are known from a single cave. We identified three biogeographic clusters of troglobionts. Two clusters are located in the northwestern part of the state, west of Lookout Mountain in Lookout Valley and east of Lookout Mountain in the Valley and Ridge. In addition, there is a group of tro- globionts found only in the southwestern corner of the state and associated with the Upper Floridan Aquifer. At least two dozen potentially undescribed species have been collected from caves; clarifying the taxonomic status of these organisms would improve our understanding of cave biodiversity in the state. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Terrestrial Ecosystems 3 Chapter 1

TERRESTRIAL Chapter 1: Terrestrial Ecosystems 3 Chapter 1: What are the history, Terrestrial status, and projected future of terrestrial wildlife habitat types and Ecosystems species in the South? Margaret Katherine Trani (Griep) Southern Region, USDA Forest Service ■ Since presettlement, there have insect infestation, advanced age, Key Findings been significant losses of community climatic processes, and distur- biodiversity in the South (Noss and bance influence mast yields. ■ There are 132 terrestrial vertebrate others 1995). Fourteen communities ■ The ranges of many species species that are considered to be are critically endangered (greater cross both public and private of conservation concern in the South than 98-percent decline), 25 are land ownerships. The numbers of by State Natural Heritage agencies. endangered (85- to 98-percent imperiled and endangered species Of the species that warrant conser- decline), and 11 are threatened inhabiting private land indicate its vation focus, 3 percent are classed (70- to 84-percent decline). Common critical importance for conservation. factors contributing to the loss of as critically imperiled, 3 percent ■ The significance of land owner- as imperiled, and 6 percent as these communities include urban development, fire suppression, ship in the South for the provision vulnerable. Eighty-six percent of species habitat cannot be of terrestrial vertebrate species exotic species invasion, and recreational activity. overstated. Each major landowner are designated as relatively secure. has an important role to play in ■ The remaining 2 percent are either The term “fragmentation” the conservation of species and known or presumed to be extinct, references the insularization of their habitats. or have questionable status. habitat on a landscape. -

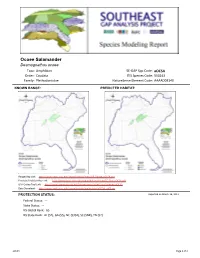

Ocoee Salamander

Ocoee Salamander Desmognathus ocoee Taxa: Amphibian SE-GAP Spp Code: aOCSA Order: Caudata ITIS Species Code: 550243 Family: Plethodontidae NatureServe Element Code: AAAAD03140 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_aOCSA.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_aOCSA.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=aOCSA Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/aOCSA_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: --- NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: AL (S2), GA (S5), NC (S3S4), SC (SNR), TN (S2) aOCSA Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 2,876.8 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 12,140.1 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 82,194.8 21 470.4 < 1 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 97,211.7 25 470.4 < 1 0.0 0 US Dept. of Energy US Nat. Park Service NOAA Other Federal Lands ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 34,140.2 9 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 282.7 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 34,422.8 9 0.0 0 0.0 0 Native Am. -

Intraerythrocytic Rickettsial Inclusions in Ocoee Salamanders (Desmognathus Ocoee): Prevalence, Morphology, and Comparisons with Inclusions of Plethodon Cinereus

Parasitol Res DOI 10.1007/s00436-010-1869-z ORIGINAL PAPER Intraerythrocytic rickettsial inclusions in Ocoee salamanders (Desmognathus ocoee): prevalence, morphology, and comparisons with inclusions of Plethodon cinereus Andrew K. Davis & Kristen Cecala Received: 4 December 2009 /Accepted: 1 April 2010 # Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Reports of an unusual intraerythrocytic pathogen Introduction in amphibian blood have been made for decades; these pathogens appear as membrane-bound vacuoles within Salamanders are hosts to a variety of parasites, including erythrocytes. It is now understood that the pathogen is a helminths (McAllister et al. 2008), arthropods (Westfall et Rickettsia bacteria, which are obligate intracellular para- al. 2008), and in particular, intracellular bacteria in the sites, and most are transmitted by arthropod vectors. In an order Rickettsiales (Davis et al. 2009a). All bacteria in this effort to further understand the host range and character- order are obligate, intracellular (usually within erythro- istics of this pathogen, we examined 20 Ocoee salamanders cytes) organisms that are transmitted by arthropod vectors (Desmognathus ocoee) from a site in southwest North (Rikihisa 2006). Most infections can be seen by examining Carolina for the presence of rickettsial inclusions and report stained blood smears with light microscopy and noting the the general characteristics of infections. Seven individuals presence of the characteristic inclusions that are formed (35%) were infected, and this level of prevalence was within blood cells. Such inclusions have been noted in consistent with all other members of this genus examined to amphibian blood cells for decades (Hegner 1921; Lehmann date. In contrast, infections within the genus Plethodon tend 1961; McAllister et al. -

Monitoring Amphibians in Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Monitoring Amphibians in Great Smoky Mountains National Park Circular 1258 U.S. Department of the Interior By C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr. U.S. Geological Survey Photographs by: Author unless otherwise noted, between 1998 and 2002. All animals were photographed within Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Color illustrations by: Jacqualine Grant, Cornell University. Layout: Patsy Mixson Graphic Design: Jim Tomberlin Monitoring Amphibians in Great Smoky Mountains National Park By C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1258 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, product, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. Tallahassee, Florida 2003 For additional information write to: C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr. Florida Integrated Science Center U.S. Geological Survey 7920 N.W. 71st Street Gainesville, Florida 32653 For additional copies please contact: U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Box 25286 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dodd, C. Kenneth. Monitoring Amphibians in Great Smoky Mountains National Park / by C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr. p. cm. — (U.S. Geological Survey circular ; 1258) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-607-93448-4 (alk. paper) 1. Amphibians — Monitoring — Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) 2. Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) I. Title. II. Series. -

Appalachian Salamander Cons

PROCEEDINGS OF THE APPALACHIAN SALAMANDER CONSERVATION WORKSHOP - 30–31 MAY 2008 CONSERVATION & RESEARCH CENTER, SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL ZOOLOGICAL PARK, FRONT ROYAL, VIRGINIA, USA Hosted by Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, facilitated by the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group © Copyright 2008 CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Gratwicke, B (ed). 2008. Proceedings of the Appalachian Salamander Conservation Workshop. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. To order additional copies of Proceedings of the Appalachian Salamander Conservation Workshop, contact the CBSG office: [email protected], 001-952-997-9800, www.cbsg.org. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Salamanders, along with many other amphibian species have been declining in recent years. The IUCN lists 47% of the world’s salamanders threatened or endangered, yet few people know that the Appalachian region of the United States is home to 14% of the world’s 535 salamander species, making it an extraordinary salamander biodiversity hotspot, and a priority region for salamander conservation. -

Activity Guide and Lesson Plan

Activity Guide and Lesson Plan Dear educators, The Southern Appalachian Mountains Region is not only stunningly beautiful, but one of the most biologically diverse regions in the world. To provide an example, more salamanders are found here than anywhere else on the planet. Unfortunately this biodiversity hotspot is under threat due to pollution, habitat loss and many other issues that affect many of our wild places. Instilling a passion for conservation and good stewardship towards our wild places is much needed and the Amphibian & Reptile Conservancy (ARC)- along with our sponsor, Georgia Pacific- created this packet to help our educators bring more nature into their classrooms and lesson planning . Thank you for your support by downloading this packet and sharing it with your students. We provide these resources for free and only ask for your feedback in return so we may use this information to better our education curriculums and advocate more organizations to support our education efforts. Please provide your feedback here. Southern Appalachian Awareness Campaign created by Mallory Lindsay of Ms. Mallory Adventures Salamanders of Southern Appalachian Mountains Links to digital resources Use the links below to make copies of all of these resources in Google Slides! Teacher Guide (lesson plans and printables): https://bit.ly/387g3qm Student activity slides: https://bit.ly/3kVtBZz Southern Appalachian Mountain Salamanders presentation: https://bit.ly/360KRXp Southern Appalachian Mountain Salamanders presentation video:(includes extra information about each slide!) https://bit.ly/37kJeV6 Permeable Skin Activity video: https://bit.ly/3o3Gv9h Printable coloring pages: https://bit.ly/361OgVC Southern Appalachian Awareness Campaign created by Mallory Lindsay of Ms. -

Monitoring Amphibians in Great Smoky Mountains National Park by C

Monitoring Amphibians in Great Smoky Mountains National Park By C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr. — Abstract — a national amphibian monitoring program on Federal lands, to develop the sampling techniques and bio- Amphibian species have inexplicably declined metrical analyses necessary to determine status and or disappeared in many regions of the world, and in trends, and to identify possible causes of amphibian some instances, serious malformations have been declines and malformations. observed. In the United States, amphibian declines The biological importance of Great Smoky frequently have occurred even in protected areas. Mountains National Park has been recognized by its Causes for the declines and malformations probably designation as an International Biosphere Reserve. are varied and may not even be related. The seem- As such, it is clearly the leading region of signifi- ingly sudden declines in widely separated areas, how- cance for amphibian research. Although no other ever, suggests a need to monitor amphibian region shares the wealth of amphibians as found in populations as well as identify the causes when the Great Smokies (31 species of salamanders, and declines or malformations are discovered. 13 of frogs), the entire southern and mid-section of In 2000, the President of the United States and the Appalachian Mountain chain is characterized by Congress directed Department of the Interior (DOI) a high diversity of amphibians, and inventories and agencies to develop a plan to monitor the trends in monitoring protocols developed in the Smokies likely amphibian populations on DOI lands and to conduct will be applicable to other Appalachian National Park research into possible causes of declines.