Sunbathing by Great Crested Flycatchers, Myiarchus Crinitus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lesser Antilles Incuding Trinidad

The brilliant Lesser Antillean Barn Owl again showed superbly. One of several potential splits not yet recognized by the IOC (Pete Morris) THE LESSER ANTILLES INCUDING TRINIDAD 5 – 20/25 JUNE 2015 LEADERS: PETE MORRIS After our successful tour around the Caribbean in 2013, it was great to get back again this year. It all seemed pretty straightforward this time around, and once again we cleaned up on all of the available endemics, po- 1 BirdQuest Tour Report:The Lesser Antilles www.birdquest-tours.com The fabulous White-breasted Thrasher from Martinique (Pete Morris) tential splits and other goodies. For sure, this was no ordinary Caribbean holiday! During the first couple of weeks we visited no fewer than ten islands (Antigua, Barbuda, Montserrat, Dominica, Guadeloupe, Martinique, St Lucia, St Vincent, Barbados and Grenada), a logistical feat of some magnitude. With plenty of LIAT flights (the islanders refer to LIAT as ‘Leave Island any Time’ and ‘Luggage in Another Terminal’ to name but two of the many funny phrases coined from LIAT) and unreliable AVIS car hire reservations, we had our work cut out, but in the end, all worked out! It’s always strange birding on islands with so few targets, but with so many islands to pack-in, we were never really short of things to do. All of the endemics showed well and there were some cracking highlights, including the four smart endemic amazons, the rare Grenada Dove, the superb Lesser Antillean Barn Owl, the unique tremblers and White-breasted Thrashers, and a series of colourful endemic orioles to name just a few! At the end of the Lesser Antilles adventure we enjoyed a few days on Trinidad. -

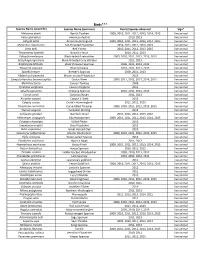

Flora and Fauna List.Xlsx

Birds*** Species Name (scientific) Species Name (common) Year(s) Species observed Sign* Melozone aberti Abert's Towhee 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Falco sparverius American Kestrel 2010, 2013 live animal Calypte anna Anna's Hummingbird 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Myiarchus cinerascens Ash‐throated Flycatcher 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Vireo bellii Bell's Vireo 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Thryomanes bewickii Bewick's Wren 2010, 2011, 2013 live animal Polioptila melanura Black‐tailed Gnatcatcher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Setophaga nigrescens Black‐throated Gray Warbler 2011, 2013 live animal Amphispiza bilineata Black‐throated Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Passerina caerulea Blue Grosbeak 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Spizella breweri Brewer's Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2013 live animal Myiarchus tryannulus Brown‐crested Flycatcher 2013 live animal Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Cactus Wren 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Melozone fusca Canyon Towhee 2009 live animal Tyrannus vociferans Cassin's Kingbird 2011 live animal Spizella passerina Chipping Sparrow 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Corvus corax Common Raven 2011, 2013 live animal Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk 2013 live animal Calypte costae Costa's Hummingbird 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Toxostoma curvirostre Curve‐billed Thrasher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Sturnus vulgaris European Starling 2012 live animal Callipepla gambelii Gambel's -

20100512 Myiarchus Flycatchers P304

Notes based on Joe Morlan’s Ornithology class lecture May 12 th , 2010. Joe Morlan is not responsible for these notes, any errors or omissions in them are mine. You can find Western Tanagers in flocks during migration. There have been occasional reports of large numbers of migrants very locally on certain ridges these last few weeks. Also a lot of reports of people seeing almost no migrants. It seems that migration is much more localized this year, not widespread. Some of the birds looked for during the class field trip to Briones did not show up. The wet winter may be a reason. Birds of arid valleys and deserts are not forced to go away from the dry interior, they may have enough water there to be able to nest locally instead of being pushed far. When there are invasions of species like Black-throated Sparrows there was usually a wet year followed by a draught. They have excellent breeding success during the wet year and then there are too many birds during the draught, they get pushed into areas where they would not normally be. Bird nest boxes come in different sizes and with different hole sizes that have been specified for particular birds. Also the height at which you put up the box can affect which species you get. Starlings do not like to nest in bird houses that are below six or seven feet from the ground. Bluebirds are well studied nest box users because of the big decline in bluebirds due to starlings occupying old woodpecker holes. -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

(Revised with Costs), Petrified Forest National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment Petrified Forest National Park (Revised with Costs) Natural Resource Report NPS/PEFO/NRR—2020/2186 The production of this document cost $ 112,132, including costs associated with data collection, processing, analysis, and subsequent authoring, editing, and publication. ON THE COVER Milky Way over Battleship Rock, Petrified Forest National Park Jacob Holgerson, NPS Natural Resource Condition Assessment Petrified Forest National Park (Revised with Costs) Natural Resource Report NPS/PEFO/NRR—2020/2186 J. Judson Wynne1 1 Department of Biological Sciences Merriam-Powell Center for Environmental Research Northern Arizona University Box 5640 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 November 2020 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

The Status and Occurrence of Ash-Throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus Cinerascens) in British Columbia. by Rick Toochin and Jamie Fenneman

The Status and Occurrence of Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Jamie Fenneman. Introduction and Distribution: The Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens) breeds from California north throughout eastern and southwestern Oregon and north into areas of central Washington along the eastern slopes of the Cascade Range north to Wenatchee (Wahl et al. 2005). It also breeds from southern Idaho, throughout Nevada, Utah, parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, southern Oklahoma and east to central Texas, as well as throughout northern and central Mexico (Sibley 2000, Dunn and Alderfer 2011). It winters in the southwestern United States in southern California and Arizona, as well as from Florida through the Gulf States to south coastal Texas south throughout western Mexico and the Pacific slope of northern Central America, south to Nicaragua, as well as along the coast of eastern Mexico (e.g., Tamaulipas, Veracruz) (Dunn and Alderfer 2011, Howell and Webb 2010). The Ash-throated Flycatcher is rare in Costa Rica (Howell and Webb 2010). It is a rare but regular vagrant to western Washington from both coastal locations and those on the western side of the Cascade Mountains (Wahl et al. 2005). In British Columbia, the Ash-throated Flycatcher is a rare to annual species that occurs in BC in small numbers each year, with over 80 records occurring throughout the spring to fall period (Toochin et al. 2013, Please see Table 1). There is a good single observer sight record for Alaska from Juneau in July 1999 (West 2008). Identification and Similar Species: The identification of Myiarchus flycatchers, which includes Ash-throated Flycatcher can, in some cases, be extremely challenging in many areas of North and South America, particularly where multiple species occur regularly together. -

Ontario Bird Records Committee Report

Ontario Bird Records Committee Report Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens) One Juvenile, Sex unknown “Breakwater Field Station”- Long Point, Norfolk, ON August 23, 2014 - 3:20-3:25pm August 24, 2014 – 9:00am-1:00pm Optics: Nikon Monarch 8x42 binoculars Lighting and Distance: The bird was observed at a variety of ranges from 30 ft to 15 ft. It was viewed in shadows of the trees and in the sunlight. Who first saw the bird? : Tim Lucas Who first identified the bird? : Tim Lucas Other observers: Abbi MacDonald, Joe Krawiec Weather: Aug. 23: 20 C Wind NE at 4 No precipitation 10% Cloud Cover Aug. 24: 15 C No Wind No precipitation Cloud cover 10% Lighting and Distance: The bird was observed at a variety of ranges from 30 ft to 15 ft. It was viewed in shadows of the trees and the sunlight. Photos/ sketches? Yes, I photographed the bird on the 23 Aug. briefly, then later the 24 of August. Sketches were taken in the field on the 23rd, and a few things were added as they were observed on the 24th. Photos are unedited and un-cropped. Please note on the first scanned doc. of the field notes, to ignore the House Finch notes on the previous page as the ATFL notes, it is something I can’t cut out. Circumstances: Aug. 23/14 I was dropped off to breakwater by boat around noon and after settling in, I was taken on a walk of the census area by Joe Krawiec and Abbi MacDonald, the two other volunteers staying at this location. -

Towards a Phylogenetic Framework for the Evolution of Shakes, Rattles, and Rolls in Myiarchus Tyrant-flycatchers (Aves: Passeriformes: Tyrannidae)

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 31 (2004) 139–152 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Towards a phylogenetic framework for the evolution of shakes, rattles, and rolls in Myiarchus tyrant-flycatchers (Aves: Passeriformes: Tyrannidae) Leo Joseph,a,* Thomas Wilke,a,1 Eldredge Bermingham,b Deryn Alpers,a,2 and Robert Ricklefsc a Department of Ornithology, The Academy of Natural Sciences, 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, PA 19103-1195, USA b Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 2072, Balboa, Panama c Department of Biology, University of Missouri – St. Louis, 8001 Natural Bridge Road, St. Louis, MO 63121-4499, USA Received 1 May 2003; revised 25 June 2003 Abstract A phylogeny of 19 of the 22 currently recognized species of Myiarchus tyrant-flycatchers is presented. It is based on 842 bp of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences from the ATPase subunit 8 and ATPase subunit 6 genes. Except for the morphologically distinct M. semirufus, mtDNAs of the remaining 18 species fall into either of two clades. One comprises predominantly Caribbean and Central and North American taxa (Clade I), and the other is of predominantly South American taxa (Clade II). The phylogeny is only very broadly concordant with some vocal characters and also with the limited morphological diversity for which the group is well known. Paraphyly in several species (M. swainsoni, M. tuberculifer, M. ferox, M. phaeocephalus, M. sagrae, M. stolidus) suggests that morphological evolution, albeit resulting in limited morphological diversity, has been more rapid than that of mtDNA, or that current taxonomy is faulty, or both. A South American origin for Myiarchus is likely. -

The Ash-Throated Flycatcher in the East: an Overview

DISTRIBUTION, IDENTIFICATION The Ash-throated Flycatcher in the East: A western-southwesternspecies formerly regarded as an accidental visitor in the East now apparently of regular occurrence William L. Murphy N SUNDAYDECEMBER I9, I979,I catchingthem in flight, althoughinsects guishthe speciesof Myiarchus flycatch- studied an Ash-throated Fly- were flying. Although I did not have an ers found in America north of Mexico catcher (Myiarchus cinerascens) for opportunity to photograph the fly- from the Ash-throated Flycatcher. more than an hour in a brushy backyard catcher,it was seenagain two dayslater in Haymarket, Prince William County, by David Smith of Haymarket, who in- HISTORICAL SIGHTINGS Virginia. The flycatcher was initially dependently identified the bird as an perchedlow in a silver maple tree (Acer Ash-throated Flycatcher. Reports of HEASH-THROATED FLYCATCHER IS saccharinurn L.) 12 m from a kitchen the sighting with substantiating notes an insectivorousspecies of the fam- window through which I was watching. from both observerswere subsequently ily Tyrannidaethat inhabitsthe temper- The bird then flew to within 2 m of the sent to the editor of the Raven and to the ate desert and scrub communities and window and perched on a chain link area compiler for American Birds. rangesinto the pine oak woodlandsof fence. My first impressionwas that the On Sunday, January 20, 1980, Ellen western North America. Its breeding bird resembled a Great Crested Fly- G' Fader of Arlington, Virginia, and I range extends from the southern tip of catcher (Myiarchus crinitus), the com- observed an Ash-throated Flycatcher the central plateau of Mexico (southern mon Myiarchus speciesin the East--a on Virginia Key, Dade County, Florida. -

Featured Photo FIRST RECORD of MELANISM in a MYIARCHUS FLYCATCHER DEBORAH J

FEATURED PHOTO FIRST RECORD OF MELANISM IN A MYIARCHUS FLYCATCHER DEBORAH J. HOUSE, 172 Summit Road, Bishop, California 93514; [email protected] On 25 May 2008, I observed an aberrantly plumaged Brown-crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus tyrannulus) at the China Ranch Date Farm near Tecopa, in southeastern Inyo County, California (35° 48´ N, 116° 11´ W). Apart from rufous flight and tail feathers, this bird was almost entirely brownish-black—see photo on the outside back cover of this issue of Western Birds. Although it was oddly plumaged, I identified this relatively large flycatcher with a disproportionally large head, bushy crest, heavy bill, and long tail as a Myiarchus flycatcher. Furthermore, the bird appeared to be a Brown-crested Flycatcher, because of its larger size and heavier bill relative to the Ash-throated Flycatcher (M. cinera- scens), the only other Myiarchus flycatcher that nests at this location. This individual called several times, giving what has been described as the “vibrato whistle” (Cardiff and Ditmann 2000). This aberrantly plumaged bird was paired with a normally plumaged Brown-crested Flycatcher and engaged in nest building. I initially encountered the melanistic bird as it was collecting nesting material, and then as it perched out in the open on shrubs and on a tractor. The nesting material appeared to consist of dried grasses, forbs, and twigs. Upon returning to the canopy of the adjacent dense riparian thicket, the melanistic flycatcher interacted with a normally plumaged Brown-crested Flycatcher, engaging in chases and calling. During the interaction with the other bird, I heard one of the birds sing several several short “THREE-for-you” phrases, a component of the dawn song. -

The Yucatan Peninsula (Mark Van Beirs)

The charming Yucatan Wren only occurs in the extreme north of the Yucatan Peninsula (Mark Van Beirs) THE YUCATAN PENINSULA 21 FEBRUARY – 4 MARCH 2018 LEADER: MARK VAN BEIRS A very well-behaved Lesser Roadrunner posing for scope views in a derelict meadow near Rio Lagartos became the Bird of the Tour on our 2018 Yucatan trip. Our explorations of the different habitats of the Yucatan Peninsula produced many more splendid observations. The very touristy island of Cozumel yielded cute Ruddy Crakes, White-crowned Pigeon, Mangrove Cuckoo, Cozumel Emerald, Yucatan Woodpecker, Yucatan Amazon, Cozumel and Yucatan Vireos, Black Catbird and Western Spindalis. The astounding waterbird spectacle at the lagoons and mangrove-lined creeks of Rio Lagartos, situated near the northernmost tip of Yucatan is always great fun. Highlights included glorious, endemic Mexican Sheartails, 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: The Yucatan Peninsula 2018 www.birdquest-tours.com Yucatan Bobwhite, Bare-throated Tiger and Boat-billed Herons, American White Pelican, Clapper Rail, Rufous-necked and Rufous-naped Wood Rails, Kelp Gull, Yucatan Nightjar, Yucatan Wren and Orange Oriole. The dry woodland of the Sian Ka’an reserve held Middle American Screech Owl, Pale-billed Woodpecker, Tawny-winged Woodcreeper, Stub-tailed Spadebill, Couch’s Kingbird, Yucatan Flycatcher, Yucatan Jay, Green-backed Sparrow, Rose-throated Tanager and Blue Bunting. Fabulous Grey-throated Chats gave excellent views in the semi-humid forests of the magnificent Mayan archaeological site of Calakmul, where we also found impressive Great Curassows, gaudy Ocellated Turkeys, Bicoloured Hawk, Yucatan Poorwill, Lesson’s Motmot, White-bellied Wren and interesting mammals like Grey Fox and Yucatan Black Howler and Geoffroy’s Spider Monkeys. -

Molecular Taxonomy of Brazilian Tyrant-Flycatchers (Passeriformes: Tyrannidae)

Molecular Ecology Resources (2008) 8, 1169–1177 doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02218.x DNABlackwell Publishing Ltd BARCODING Molecular taxonomy of Brazilian tyrant-flycatchers (Passeriformes: Tyrannidae) A. V. CHAVES, C. L. CLOZATO, D. R. LACERDA, E. H. R. SARI* and F. R. SANTOS Departamento de Biologia Geral, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, CP 486, 31270-901, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil Abstract The tyrannids are one of the most diverse groups of birds in the world, and the most numerous suboscine family in the Neotropics. Reflecting such diversity, many taxonomic issues arise in this group, mainly due to morphological similarities, even among phylogenetically distant species. Other issues appear at higher taxonomic levels, mostly brought up by genetic studies, making systematics a rather inconclusive issue. This study looks into the use of DNA barcodes method to discriminate and identify Tyrannidae species occurring in the Atlantic Forest and Cerrado biomes of Brazil. We analysed 266 individuals of 71 tyrant-flycatcher species from different geographical locations by sequencing 542 bp of the mtDNA COI gene. The great majority of the analysed species showed exclusive haplotypes, usually displaying low intraspecific diversity and high interspecific divergence. Only Casiornis fuscus and Casiornis rufus, suggested in some studies to belong to a single species, could not be phy- logenetically separated. High intraspecific diversity was observed among Elaenia obscura individuals, which can suggest the existence of cryptic species in this taxon. The same was also observed for Suiriri suiriri, considered by some authors to comprise at least two species, and by others to be divided into three subspecies.