Status and Occurrence of Great Crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus Crinitus) in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lesser Antilles Incuding Trinidad

The brilliant Lesser Antillean Barn Owl again showed superbly. One of several potential splits not yet recognized by the IOC (Pete Morris) THE LESSER ANTILLES INCUDING TRINIDAD 5 – 20/25 JUNE 2015 LEADERS: PETE MORRIS After our successful tour around the Caribbean in 2013, it was great to get back again this year. It all seemed pretty straightforward this time around, and once again we cleaned up on all of the available endemics, po- 1 BirdQuest Tour Report:The Lesser Antilles www.birdquest-tours.com The fabulous White-breasted Thrasher from Martinique (Pete Morris) tential splits and other goodies. For sure, this was no ordinary Caribbean holiday! During the first couple of weeks we visited no fewer than ten islands (Antigua, Barbuda, Montserrat, Dominica, Guadeloupe, Martinique, St Lucia, St Vincent, Barbados and Grenada), a logistical feat of some magnitude. With plenty of LIAT flights (the islanders refer to LIAT as ‘Leave Island any Time’ and ‘Luggage in Another Terminal’ to name but two of the many funny phrases coined from LIAT) and unreliable AVIS car hire reservations, we had our work cut out, but in the end, all worked out! It’s always strange birding on islands with so few targets, but with so many islands to pack-in, we were never really short of things to do. All of the endemics showed well and there were some cracking highlights, including the four smart endemic amazons, the rare Grenada Dove, the superb Lesser Antillean Barn Owl, the unique tremblers and White-breasted Thrashers, and a series of colourful endemic orioles to name just a few! At the end of the Lesser Antilles adventure we enjoyed a few days on Trinidad. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

The Physiological Implications of Ingesting Fresh-Water Mussel Shells to Great Crested Flycatchers

The Physiological Implications of Ingesting Fresh-water Mussel Shells to Great Crested Flycatchers Nathan H. Rice1 and Alex J. Cohen2 Introduction The Great Crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus contained two Asian clam (Corbicula fluminea) shells crinitus) is a migratory songbird that breeds in the (ca. 8 x 8 mm) that were common along the stream in eastern half of North America and winters in Central this area. America (Lanyon 1997). Like other tyrannids, the Great Crested Flycatcher feeds primarily on flying Discussion insects that are captured during characteristic sorties Beal (1912) reported on the stomach contents from upper canopy perches. Here we report on of 265 Great Crested Flycatchers and found that unusual foraging and diet by female Great Crested 93.7% of them contained animal matter (primarily Flycatchers during the breeding season. insects). Interestingly, three individuals were found to have lizard bones in their stomachs. During times We conducted field work along the Neshaminy of drought and decreased insect numbers, Brown- Creek near Newtown (40°13´45´´N, 74°56´14´´W) crested Flycatchers (M. tyrannulus) have been in eastern Bucks County, Pennsylvania, from 11-17 observed catching and eating lizards and May 2000. The field site is primarily agricultural hummingbirds (Cardiff and Dittman 2000, Gamboa (corn) with old second growth hardwood forests 1977, Snider 1971a, 1971b). Thus, it appears that (Quercus, Acer, and Carya) intermingled with the during times of physical stress (migration, drought, agricultural fields. Forests along this portion of etc.), Myiarchus flycatchers may shift their diets from Neshaminy Creek are tall (ca. 30 meters) with a primarily insectivorous to include opportunistically complete canopy, although generally not more than small vertebrate prey items. -

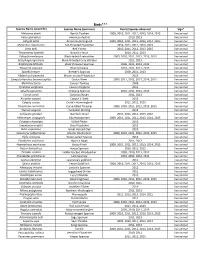

Flora and Fauna List.Xlsx

Birds*** Species Name (scientific) Species Name (common) Year(s) Species observed Sign* Melozone aberti Abert's Towhee 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Falco sparverius American Kestrel 2010, 2013 live animal Calypte anna Anna's Hummingbird 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Myiarchus cinerascens Ash‐throated Flycatcher 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Vireo bellii Bell's Vireo 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Thryomanes bewickii Bewick's Wren 2010, 2011, 2013 live animal Polioptila melanura Black‐tailed Gnatcatcher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Setophaga nigrescens Black‐throated Gray Warbler 2011, 2013 live animal Amphispiza bilineata Black‐throated Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Passerina caerulea Blue Grosbeak 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Spizella breweri Brewer's Sparrow 2009, 2011, 2013 live animal Myiarchus tryannulus Brown‐crested Flycatcher 2013 live animal Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Cactus Wren 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 live animal Melozone fusca Canyon Towhee 2009 live animal Tyrannus vociferans Cassin's Kingbird 2011 live animal Spizella passerina Chipping Sparrow 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Corvus corax Common Raven 2011, 2013 live animal Accipiter cooperii Cooper's Hawk 2013 live animal Calypte costae Costa's Hummingbird 2011, 2012, 2013 live animal Toxostoma curvirostre Curve‐billed Thrasher 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015 live animal Sturnus vulgaris European Starling 2012 live animal Callipepla gambelii Gambel's -

20100512 Myiarchus Flycatchers P304

Notes based on Joe Morlan’s Ornithology class lecture May 12 th , 2010. Joe Morlan is not responsible for these notes, any errors or omissions in them are mine. You can find Western Tanagers in flocks during migration. There have been occasional reports of large numbers of migrants very locally on certain ridges these last few weeks. Also a lot of reports of people seeing almost no migrants. It seems that migration is much more localized this year, not widespread. Some of the birds looked for during the class field trip to Briones did not show up. The wet winter may be a reason. Birds of arid valleys and deserts are not forced to go away from the dry interior, they may have enough water there to be able to nest locally instead of being pushed far. When there are invasions of species like Black-throated Sparrows there was usually a wet year followed by a draught. They have excellent breeding success during the wet year and then there are too many birds during the draught, they get pushed into areas where they would not normally be. Bird nest boxes come in different sizes and with different hole sizes that have been specified for particular birds. Also the height at which you put up the box can affect which species you get. Starlings do not like to nest in bird houses that are below six or seven feet from the ground. Bluebirds are well studied nest box users because of the big decline in bluebirds due to starlings occupying old woodpecker holes. -

ITC Iowa Environmental Overview: Rare Species and Habitats Linn County, IA June 8Th, 2016 SCHEDULE

ITC IOWA ENVIRONMENTAL OVERVIEW: RARE SPecies AND HABITAts Linn County, IA June 8th, 2016 SCHEDULE MEETING PLACE: Days Inn and Suites of Cedar Rapids (Depart at 7:00 am) • 2215 Blairs Ferry Rd NE, Cedar Rapids, IA 52402 STOP 1: Highway 100 Extension Project and Rock Island Botanical Preserve (7:15 am-10:45 am) • Ecosystems: Emergent Wetland, Dry Sand Prairie, Sand Oak Savanna, River Floodplain Forest • T&E Species : Northern long-eared bat, Prairie vole, Western harvest mouse, Southern flying squirrel, Blanding’s turtle, Bullsnake, Ornate box turtle, Blue racer, Byssus skipper, Zabulon skipper, Wild Indigo duskywing, Acadian hairstreak, Woodland horsetail, Prairie moonwort, Northern Adder’s-tongue, Soft rush, Northern panic-grass, Great Plains Ladies’-tresses, Glomerate sedge, Goats-rue, Field sedge, Flat top white aster • Invasive Species: Garlic mustard, Common buckthorn, Eurasian honeysuckles, Autumn-olive, Yellow & White sweet-clover, Common mullein, Bouncing bet, Kentucky bluegrass, Siberian elm, Japanese barberry, White mulberry, Smooth brome LUNCH: BurgerFeen (11:00 am – 12:00 pm) • 3980 Center Point Rd NE, Cedar Rapids, IA 52402 STOP 2: McLoud Run (12:15 pm – 2:45 pm) • Current Ecosystems: Disturbed Floodplain Forest • T&E Species: none • Invasive Species: Black locust, Bird’s-foot trefoil, Bouncing bet, Crown vetch, Cut-leaved teasel, Eurasian Honeysuckles, Garlic mustard, Japanese knotweed, Reed canary grass, Siberian elm, Tree-of-heaven, White mulberry, Wild parsnip RETURN TO HOTEL (3:00 pm) Martha Holzheuer, LLA, CE, CA Matt -

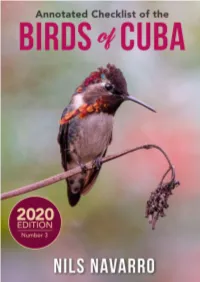

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Florida Field Naturalist Published by the Florida Ornithological Society

Florida Field Naturalist PUBLISHED BY THE FLORIDA ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOL. 42, NO. 2 MAY 2014 PAGES 45-90 Florida Field Naturalist 42(2):45-53, 2014. GREAT CRESTED FLYCATCHER (Myiarchus crinitus) NEST-SITE SELECTION AND NESTING SUCCESS IN TREE CAVITIES KARL E. MILLER1 Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, P.O. Box 110430, Gainesville, Florida 32611 1Current address: Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, 1105 SW Williston Road, Gainesville, Florida 32601 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Nesting ecology of the Great Crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus crinitus) has rarely been studied, even though the species is widespread and relatively common. I provide here the first study of Great Crested Flycatcher nesting ecology and nest-site selection in tree cavities in the eastern United States. I monitored 44 Great Crested Flycatcher nests in a mosaic of slash pine plantations and longleaf pine sandhills in Clay County, Florida. Nest sites were located in slash pine (52%), turkey oak (39%), longleaf pine (7%), and unknown pine species (2%). Most (73%) Great Crested Flycatcher nests were located in abandoned tree cavities excavated by various species, especially the Red-bellied Woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus). Cavity entrance diameters averaged 6.2 (± 2.5) cm, with most (55%) measured entrances smaller than the minimum previ- ously reported for the species. These findings are contrary to earlier characterizations of the species as showing a strong affinity for large naturally occurring hollows in live trees. Only 19 of 44 Great Crested Flycatcher nests (43%) were successful in fledging≥ 1 young. Mean cavity height was greater for successful nests than for unsuccessful nests, and the primary cause of nest failure was predation. -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

(Revised with Costs), Petrified Forest National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment Petrified Forest National Park (Revised with Costs) Natural Resource Report NPS/PEFO/NRR—2020/2186 The production of this document cost $ 112,132, including costs associated with data collection, processing, analysis, and subsequent authoring, editing, and publication. ON THE COVER Milky Way over Battleship Rock, Petrified Forest National Park Jacob Holgerson, NPS Natural Resource Condition Assessment Petrified Forest National Park (Revised with Costs) Natural Resource Report NPS/PEFO/NRR—2020/2186 J. Judson Wynne1 1 Department of Biological Sciences Merriam-Powell Center for Environmental Research Northern Arizona University Box 5640 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 November 2020 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

The Status and Occurrence of Ash-Throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus Cinerascens) in British Columbia. by Rick Toochin and Jamie Fenneman

The Status and Occurrence of Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Jamie Fenneman. Introduction and Distribution: The Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens) breeds from California north throughout eastern and southwestern Oregon and north into areas of central Washington along the eastern slopes of the Cascade Range north to Wenatchee (Wahl et al. 2005). It also breeds from southern Idaho, throughout Nevada, Utah, parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, southern Oklahoma and east to central Texas, as well as throughout northern and central Mexico (Sibley 2000, Dunn and Alderfer 2011). It winters in the southwestern United States in southern California and Arizona, as well as from Florida through the Gulf States to south coastal Texas south throughout western Mexico and the Pacific slope of northern Central America, south to Nicaragua, as well as along the coast of eastern Mexico (e.g., Tamaulipas, Veracruz) (Dunn and Alderfer 2011, Howell and Webb 2010). The Ash-throated Flycatcher is rare in Costa Rica (Howell and Webb 2010). It is a rare but regular vagrant to western Washington from both coastal locations and those on the western side of the Cascade Mountains (Wahl et al. 2005). In British Columbia, the Ash-throated Flycatcher is a rare to annual species that occurs in BC in small numbers each year, with over 80 records occurring throughout the spring to fall period (Toochin et al. 2013, Please see Table 1). There is a good single observer sight record for Alaska from Juneau in July 1999 (West 2008). Identification and Similar Species: The identification of Myiarchus flycatchers, which includes Ash-throated Flycatcher can, in some cases, be extremely challenging in many areas of North and South America, particularly where multiple species occur regularly together.