Makin' Shavin's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPTIMIZATION of BURNISHING PROCESS PARAMETERS on DIFFERENTLY HARDENED 20Mncr5 STEEL

OPTIMIZATION OF BURNISHING PROCESS PARAMETERS ON DIFFERENTLY HARDENED 20MnCr5 STEEL 1HIMANSHU KHANNA, 2HARISH PUNGOTRA, 3SANDEEP GANDOTRA 1M.TECH. STUDENT, BEANT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY GURDASPUR, PUNJAB 2ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING, BEANT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, GURDASPUR - 143521, PUNJAB, INDIA 3ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING, BEANT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, GURDASPUR - 143521, PUNJAB, INDIA E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Surface finish designates the geometry and microstructural superiority of the machined surface. Different operations such as grinding, lapping, honing, buffing, barrel rolling, polishing, super finishing, and burnishing are required to be performed to achieve the high surface finish. Amongst all, burnishing is a process where the hard roller or a ball tool is engaged to the workpiece to get the better surface finish. In the present study, using Taguchi approach preliminary plan is made for the experimentation then according to it a roller burnishing of the 20MnCr5 workpiece at different input conditions is performed. From the analysis, it is concluded that the hardness of the material is the main contributing factor for burnishing process. Keywords - Burnishing, Depth of penetration, Feed, Speed, Hardness, Surface roughness. I. INTRODUCTION Morimoto & Tamamura (1991) compared different types of ball burnishing tools and concluded that the For reliable performance and prolonged life of cemented carbide and silicon nitride ceramic ball-tool contemporary machinery, its components require not tool showed best results regarding surface roughness. only high geometrical and dimensional geometrical Hassan et al. (1996) compared machined and accuracy but also with low surface roughness. The burnished specimens of commercially pure surface roughness has a vital role in functional aluminium and brass material. -

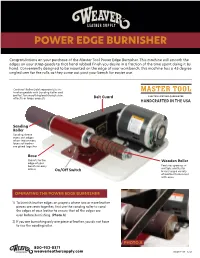

Power Edge Burnisher

POWER EDGE BURNISHER Congratulations on your purchase of the Master Tool Power Edge Burnisher. This machine will smooth the edges on your strap goods to that hand rubbed finish you desire in a fraction of the time spent doing it by hand. Conveniently designed to be mounted on the edge of your workbench, this machine has a 45 degree angled arm for the rolls so they come out past your bench for easier use. Cordura® Roller (sold separately) is in- terchangeable with Sanding Roller and perfect for smoothing back/rough side LIMITED LIFETIME GUARANTEE of belts or larger projects Belt Guard HANDCRAFTED IN THE USA Sanding Roller Sanding sleeve evens out edges when two or more layers of leather are glued together Base Mounts to the Wooden Roller edge of your bench for easy Features grooves in access multiple widths for On/Off Switch burnishing a variety of leather thicknesses with ease OPERATING THE POWER EDGE BURNISHER 1) To burnish leather edges on projects where two or more leather pieces are sewn together, first use the sanding roller to sand the edges of your leather to ensure that all the edges are even before burnishing. (Photo A) 2) If you are burnishing only one piece of leather, you do not have to use the sanding roller. PHOTO A 800-932-8371 weaverleathersupply.com INSERT-137 6/21 OPERATING THE MACHINE 3) Next, apply Gum Tragacanth (item #50-2074) or Tokonole (50210-500-212) on the edges of your leather by using a wool dauber or a bottle with a small tip. -

Mirage 27” Propane Burnisher IMPORTANT MACHINE INFORMATION

Parts and Instruction Manual - Mirage 27” Propane Burnisher IMPORTANT MACHINE INFORMATION DATE OF PURCHASE: _________________________________________________________ PURCHASED FROM: __________________________________________________________ ADDRESS: __________________________________________________________________ CITY: ____________________________STATE:_____________________ZIP:____________ PHONE: __________________________ CONTACT: ________________________________ MACHINE MODEL #:___________________ SERIAL #:_______________________________ ENGINE MODEL #:_______________________ SERIAL #:_____________________________ OWNERS INFORMATION NAME: ___________________________BUSINESS NAME: __________________________ PHONE #:________________________EMAIL ADDRESS: ____________________________ Parts and Instruction Manual - Mirage 27” Propane Burnisher Page I INTRODUCTION Operators Manual Mirage 27” Propane Burnisher This book has important information for the use and safe operation of propane powered floor burnishers. Failure to read this book prior to operating or attempting any service or maintenance procedure to your Minuteman machine could result in injury to you or to other personnel. Damage to the machine or to other property could occur as well. You must have training in the operation of this machine before using it. If your operator(s) cannot read English please have this manual explained fully before attempting to operate this machine. Este libro contiene información importante para el uso correcto y seguro de gas propano máquinas abrillantadoras. -

Repivoting Arbors - Slip Fit & Loctite Method Also “The Polishing and Burnishing of Arbors”

Repivoting Arbors - Slip fit & Loctite Method Also “The Polishing and Burnishing of Arbors” Another of the more advanced clockmaking tasks is the repivoting of arbors to replace worn or broken pivots. As with many aspects of clockmaking, there are a couple of approaches to this task. Ultimately, the replacement pivot needs to be concentric and properly burnished and this article discusses the “slip fit & Loctite method” which is the approach I used to successfully pass that part of my AWCI Certified Clockmaker exam. SECTION I: Repivoting Arbors Step 1: Determine Original Dimensions: Measure pivot diameter, pivot length, arbor shoulder to shoulder. Goal is to replicate the original dimensions for the certification test. This is not as critical in real practice as one can re-bush the pivot hole. a. Use the Vernier calipers to measure the shoulder to shoulder dimension. b. Use the micrometer for pivot diameter c. Use 1/100th or 1/64th ruler for pivot length Step 2: Check Lathe for Truth: Place male centers in headstock and tailstock to check for alignment. If they are not perfectly aligned, Loosen headstock & tailstock, realign until the male centers are pointed directly at each other and then snug up the headstock & tailstock. Recheck the male centers and if aligned, remove the male centers. If not aligned, which can happen after snugging them up, repeat the aforementioned re-alignment process. Step 3: Check Wheel for Truth: Fit up wheel in lathe & check wheel, arbor and remaining pivot for truth. Oppose arbor and pivot against a male center in the tailstock and adjust them as necessary. -

Sharpen a Scraper... and Put It to Work Turn a Hook and Watch the Shavings fl Y by Andy Rae

Sharpen a Scraper... and Put It To Work Turn a hook and watch the shavings fl y By Andy Rae When smoothing wood, I reach for a rectangle of steel called a card scraper. Despite its humble appearance, a card scraper is remarkably versatile remove hardened glue, smooth at re�ining surfaces. It will exposed joints, and smooth and level dif�icult woods and it more maneuverable than a planea �inish. for Its reaching small size into makes tight spots, so you can preserve your supply of sandpaper. A scraper does it better, faster and without annoying dust. Scrapers come in all sorts beof shapesused in and specially sizes, includingdesigned planescurved and and scraper pro�iled. holders. Some can But my daily scraper is the card scraper, either thin (0.020- 0.025") or thick (0.30-.0.040") depending on the job at hand. Thinner scrapers excel at delicate work, where light cuts and 24 woodcraftmagazine.com Oct/Nov 2015 Sharpen a Scraper... and Put It To Work Scraper job descripti on scrapers are best for heavier work:�inesse smoothing are required. tabletops, Thicker removing milling marks, and the like. For most applications, the scraping work is done by a small hook along the working edge. With a little practice, you can use this tool to produce tiny shavings, even on hard and when worked with a plane. �igured woods that show tearout Smoothing fi gured wood is Leveling between coats enables to work properly, and I’ll show the perfect scraper assignment you to remove drips and other youScrapers how this require can be sharpening done with a because planing the workpiece surface irregulariti es in order to few basic tools. -

Antares, Inc. Fact Sheets Surface Engraving © 2011 - Antares, Inc

Antares, Inc. Fact Sheets Surface Engraving © 2011 - Antares, Inc. Section One - Burnishing Description Burnishing is a surface marking technique intended for coated metals - usually lacquered brass - where the coating is removed to expose the bare metal. It is a method of rotary engraving on metals that tends to bridge the gap between diamond drag (scratch engraving) and routing. The biggest advantage of burnishing is that it enables the engraver to produce wider line widths than are obtainable with a diamond graver with- out having to cut deeply into the metal. Burnishers can be used with single and multiple line fonts, and are excellent for producing detailed line and logo work on metal. Burnishing offers the ability to create enhanced effects on both lettering and graphics and is relatively simple process. Rotating Tools Non-Rotating Point Variable Tip Sizes Tip Only Cutting with Depth Surface Marking Only Application The most common application is on the brass plates on trophies and plaques. This “trophy brass” is a rela- tively hard material that yields excellent burnishing results. It is available in various gold tones with clear or colored lacquer coatings. When burnishing the gold material, the lacquer is removed exposing the bare metal. The burnished areas can then be oxidized or blackened resulting in a gold plate with contrasting black letters. (See “Color Filling Fact Sheet”). When burnishing the colored materials, the result is a colored plate with contrasting gold letters without the need for further treatment. Burnishing can also be done on materials other than brass. However, much of the success or failure de- pends on the hardness of the material. -

Roberson Etching Plates Roberson Etching

Roberson Etching Plates Roberson Etching Presses Size MOQ ExVat IncVat Size ExVat IncVat Roberson Zinc Jet Plate – 1.0 mm Discount Code B Studio Etching Press with Stand. No Gear. Discount Code NET Pre-backed plate, polished on one side. Stop out varnish not Type of Print: All intaglio/etching engraving and woodcuts. All required. Thickness: 1.0 mm relief, linocuts and collographs. Made to order. CR96050 50 x 50 mm 1 6.08 7.30 T52100B Bed size: 52 x 100 cm 1,850.00 2,220.00 CR96100 100 x 100 mm 1 7.67 9.20 Rollers Diameter 110 mm CR96150 150 x 100 mm 1 10.67 12.80 Weight 89 kg CR96200 200 x 150 mm 1 18.50 22.20 £50 delivery within UK mainland CR96250 250 x 200 mm 1 28.92 34.70 CR96300 300 x 250 mm 1 41.08 49.30 CR96400 400 x 300 mm 1 64.00 76.80 CR96450 450 x 300 mm 1 72.17 86.60 CR96500 500 x 400 mm 1 100.67 120.80 CR96000 1000 x 500 mm 1 242.58 291.10 Roberson Polished Copper – 1.0 mm Discount Code B Protected mirror finish. Thickness: 1.0 mm CR97050 50 x 50 mm 1 3.08 3.70 CR97100 100 x 100 mm 1 5.17 6.20 CR97150 150 x 100 mm 1 6.92 8.30 CR97200 200 x 150 mm 1 11.00 13.20 CR97250 250 x 200 mm 1 16.25 19.50 CR97300 300 x 200 mm 1 18.58 22.30 CR97305 300 x 250 mm 1 22.92 27.50 CR97450 450 x 300 mm 1 38.67 46.40 CR97500 500 x 400 mm 1 54.67 65.60 CR97600 600 x 450 mm 1 71.67 86.00 CR97000 1200 x 600 mm 1 171.00 205.20 Discount Code NET Professional Studio Press with Stand. -

Advance PBU Burnisher Service Manual 04-2015

For cleaning machines, parts & supplies click/visit www.southeasternequipment.net PBU Propane Floor Burnisher 21 KACAT 27 KACAT Base Model Base Model 21 KACAT CLDC 27 KACAT CLDC Dust Control Model Dust Control Model Service Manual Model Numbers: 56384165 PBU 21KACAT 56384167 PBU 21KACATCLDC 56384166 PBU 27KACAT 56384168 PBU 27KACATCLDC English 04/15 Form No. 56043169 For cleaning machines, parts & supplies click/visit www.southeasternequipment.net Service Manual – PBU Propane Floor Burnisher Contents ii Contents General Information 4 General Machine Description 4 Service Manual Purpose and Application 4 Other Reference Manuals and Information Sources 4 Document Revision History 4 Safety Information 4 Symbols 4 General Safety Messages 5 Nameplate 6 Component Locations 6 Specifications 7 Maintenance Schedule 8 Burnishing System 9 Functional Description 9 Component Locations 9 Troubleshooting 10 Clutch Circuit Troubleshooting 10 Removal and Installation 11 Burnishing Pad Holder 11 Drive Belt 12 Burnishing Clutch 13 Clutch Switch 13 Engine System 14 Component Locations 14 Maintenance and Adjustments 15 Maintenance Specifications 15 Cooling Air Filter 15 Intake Air Filter 16 Oil and Filter Change 17 Spark Plug Change 18 Troubleshooting 19 Fuel System 24 Throttle Cable Position 24 Throttle High Idle Position 25 Carburetor Low Idle 25 Fuel Regulator/Fuel Mixture 26 Low Idle Mixture 27 High Idle (Full Load) Mixture 27 Intake Manifold 28 Exhaust System 29 Muffler/Exhaust Manifold 29 Ignition/Electrical System 30 Starter 30 Voltage Regulator 31 -

Lustersheen the Burnisher Aka the Pine Brush

Lustersheen 866 – 3 4 3 – 3 3 7 7 The Burnisher aka the Pine Brush There is no better tool for working with wax than this brush. If you are trying to achieve a high, hard luster with the European hard finish waxes like Briwax, Lustra and Classic this is the tool to do it with. Not only is it a real time and labor saver, but it does bring the wax to a higher and harder luster than can usually be achieved by hand. The Tampico bristles push deep into recesses of carvings and moldings, and also deep into the pores of an open surface, which results in more of the wax being burnished and brought to a luster. Often, when buffing by hand on porous surfaces, a cloth or lamb’s wool rides above and glides on the high points. These high points are burnished, but the lows are left untouched. That is why when buffed and burnished with "The Burnisher" there is more luster because in actuality more surface area of the wax has been burnished. Remember, if you are trying to achieve a high, hard lustrous wax finish, the key is applying an optimally thin coat / film or application. It is this thin film which should then be buffed and burnished to a luster. Excess wax needs to be removed, and makes for streaks and a gummy wax film which easily “prints” and picks up marks, condensation rings and finger prints. Finishing waxes are at their highest, hardest luster when optimally thin. 1) Apply the finishing wax, usually with #0000 steel wool, to a thin film, working it on to the substrate thoroughly. -

The Anarchist's Tool Chest" by Christopher Schwarz

An Index To "The Anarchist's Tool Chest" By Christopher Schwarz A List of Photographs & Illustrations A List of Personages Mentioned Notable Quotes Index created by Suzanne Ellison Published by Lost Art Press LLC Copyright 2011 An Index to "The Anarchist's Tool Chest" -- A -- Anarchy: 10, 24-27, 339-353, 459-460 aesthetics 10, 346-347 Cincinnati Time Store 343-344 craftsmanship 349-350 design 350-351 'Josiah Warren: The First American Anarchist' (quote) 347-348 'Native American Anarchism' (quote) 24, 347 switching from money to time 342-346 tools 351-353 tool chests 353 woodworker's perspective 24-27 Appendices: 463-471 tool list comparison (1658-1973) 463-466 tool dealers & organizations 467-471 Appliances for the workshop: 283-306 bench hook 283-285 cork-backed sanding block 293-294 end grain shooting board 287-290 long grain shooting board 290-291 mitre box 286-287 mitre shooting board 291-293 sawbenches 285-286 workbench & rules for 294-306, see Workbench Arkansas Chris Schwarz and 35, 44-46, 187 oilstones hard & soft 269-270 Auger bits: 30, 218-222 auger bit file 221 cleaning 220 cutting lip 221-222 lead screws 219-222 spirals 222 spurs 221 Awls: 31, 224-226 birdcage 31, 224-225 brad 225 marking 225-226 -- B -- Band saw: 42-43, 182 Bailey (style) plane: 63 Bathing suit area: 51 Beading plane, see Planes Beckets: see Exterior Add-ons under Tool Chest Bench hook: 31, 283-285 Bench planes, see Planes Belt sander: 41 Birdcage awl, see Awl Block plane, see Planes Boat building expressions: 115-116 Bombproof (or bulletproof) joinery: 350, 361, 419 Bowsaw, see Saws Boxwood rules: 130-132 buying 130-131 graduations 131 left & right reading 132 lightening the boxwood 132 Brace: 30, 212-216 chuck 214 features 213-214 pad 216 ratcheting 215 sweep 214-215 Brad point bits: 32, 223-224 HSS (high speed steel) 223 quality 223-224 Burning an inch: 133 Burnisher (for card scraper): 30, 279-281, see Sharpening Systems Buying tools: 50-56, 62, 467-471 Appendix 467-471 bench planes 62 new tools 53-55 vintage tools 50-53 -- C -- Cabinet scraper (No. -

Handwork the Only Hand Tools I Really Need from Milling and Layout to Fitting Joints and Smoothing, This Tidy Kit Does It All

handwork The only hand tools I really need FROM MILLING AND LAYOUT TO FITTING JOINTS AND SMOOTHING, THIS TIDY KIT DOES IT ALL BY GARRETT HACK am fortunate to teach woodworking classes around the United States, in Canada, and in faraway places such as Japan and Germany. I learned early on that I need my own tools with me when I teach, ones that I know well and that are dependable, perfectly tuned, and sharp. Through the years, I’ve worked to minimize Ithe number of tools in my kit. It has to be complete enough to build a whole project, yet light enough to carry through airports and on buses and trains. Although I am still fine-tuning my kit—replacing a tool with a lighter version, for example—it’s proven to be lean and capable of a wide range of work. When it comes to hand tools, this kit contains all I need. Garrett Hack is a contributing editor. COPYRIGHT 2017 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted. • Fine Woodworking #265 - Tools & Shops Winter 2018 LOW-ANGLE JACK PLANE AND EXTRA BLADE Good for everything from jointing stock to smoothing and shooting. The extra blade is cambered for smoothing. PLANES AND SCRAPERS CARD SCRAPERS Choosing planes to include in the kit was tough, because they should be few AND BURNISHER in number but able to perform a wide variety of work. A jack plane and two Card scrapers level block planes can handle just about any planing task outside of joinery, and a surfaces and clean shoulder plane gets the job done there. -

Cabinet Scraper

Cabinet Scraper 05P32.05 The Veritas® Cabinet Scraper is a very versatile tool, capable of both rough and fi ne work. As supplied, both edges of the blade are ground at 45° and need only burnishing for rough work such as removing paint, glue squeeze-out prior to planing, dirt or old fi nish. By honing the blade before burnishing the edges, the scraper can be used to smooth highly fi gured wood with no danger of tear-out, producing a surface that can rival a fi ne smoothing plane. The double-edged blade halves the number of sharpening sessions. The handles are designed to allow an effective two-handed grip with the force of the stroke directly in line with the cutting edge. The type of cutting action generated by this tool is ideal for hardwood but generally unsuitable for fi ne work on soft woods such as pine, butternut, basswood and cedar, although Blade Clamp Screw Camber Screw Body Clamp Bar Figure 1: Cabinet scraper components. it will still be useful for rough work such as cleaning off glue. Sharpening Remove the lacquer coating on a new blade. The scraper blade is supplied with both its edges ground at 45°. Depending on the type of work you will be doing with the cabinet scraper and the condition of the blade, you may not need to follow all the steps detailed below. For example, if you wish to get started on rough work, go directly to Step 3 — Burnishing. For fi ne work with a new blade, start with Step 2 — Honing, but for sharpening 2 a used blade, start with Step 1 — Preparation.