Vol. 17 No. 1 Pacific Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GSA TODAY Conference, P

Vol. 10, No. 2 February 2000 INSIDE • GSA and Subaru, p. 10 • Terrane Accretion Penrose GSA TODAY Conference, p. 11 A Publication of the Geological Society of America • 1999 Presidential Address, p. 24 Continental Growth, Preservation, and Modification in Southern Africa R. W. Carlson, F. R. Boyd, S. B. Shirey, P. E. Janney, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 5241 Broad Branch Road, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20015, USA, [email protected] T. L. Grove, S. A. Bowring, M. D. Schmitz, J. C. Dann, Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA D. R. Bell, J. J. Gurney, S. H. Richardson, M. Tredoux, A. H. Menzies, Department of Geological Sciences, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7700, South Africa D. G. Pearson, Department of Geological Sciences, Durham University, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK R. J. Hart, Schonland Research Center, University of Witwater- srand, P.O. Box 3, Wits 2050, South Africa A. H. Wilson, Department of Geology, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa D. Moser, Geology and Geophysics Department, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0111, USA ABSTRACT To understand the origin, modification, and preserva- tion of continents on Earth, a multidisciplinary study is examining the crust and upper mantle of southern Africa. Xenoliths of the mantle brought to the surface by kimber- lites show that the mantle beneath the Archean Kaapvaal Figure 2. Bouguer gravity image (courtesy of South African Council for Geosciences) craton is mostly melt-depleted peridotite with melt extrac- across Vredefort impact structure, South Africa. Color scale is in relative units repre- senting total gravity variation of 90 mgal across area of figure. -

Bislama Into Kwamera: Code-Mixing and Language Change on Tanna (Vanuatu)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Vol. 1, No. 2 (December 2007), pp. 216–239 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ Bislama into Kwamera: Code-mixing and Language Change on Tanna (Vanuatu) Lamont Lindstrom University of Tulsa People throughout Vanuatu frequently mix Bislama (that country’s national Pidgin) into their vernaculars. Extensive code-mixing is an obvious indicator, and sometime cause, of language change or even language replacement. This paper discusses several sorts of Bislama code-mixing on Tanna among speakers of that island’s Kwamera language. It assesses levels and kinds of Bislama use in four village debates, tape-recorded in 1982 and 1983. Among other uses, Kwamera speakers mix Bislama when interjecting, reiterating, reporting speech, neutralizing marked vernacular terms, and qualifying what they say. The paper concludes with some remarks on the phonological, morphological/syntactic, and lexical/semantic consequences of recurrent language mixing—on how Islanders’ insertions of Bislama into their oratorical and everyday talk may or may not be effecting linguistic change in Kwamera. Bislama, so far at least, has enriched more than it has impoverished Tanna’s linguistic ecology. Speakers’ frequent Bislama mixes have not yet seriously undermined their vernacular. 1. INTRODUCTION. On the island of Tanna, Vanuatu, many people say that they don’t speak their language the way they used to. This language is Kwamera—or, to give it its local name, Nɨninɨfe1 or Nɨfe (Lindstrom 1986; Lindstrom and Lynch 1994). Around 3,500 people living along Tanna’s southeastern coasts speak Kwamera. -

Re-Membering Quirós, Bougainville and Cook in Vanuatu

Chapter 3 The Sediment of Voyages: Re-membering Quirós, Bougainville and Cook in Vanuatu Margaret Jolly Introduction: An Archipelago of Names This chapter juxtaposes the voyages of Quirós in 1606 and those eighteenth-century explorations of Bougainville and Cook in the archipelago we now call Vanuatu.1 In an early and influential work Johannes Fabian (1983) suggested that, during the period which separates these voyages, European constructions of the ªotherº underwent a profound transformation. How far do the materials of these voyages support such a view? Here I consider the traces of these journeys through the lens of this vaunted transformation and in relation to local sedimentations (and vaporisations) of memory. Vanuatu is the name of this archipelago of islands declared at independence in 1980 ± vanua ªlandº and tu ªto stand up, endure; be independentº (see figure 3.1). Both words are drawn from one of the 110 vernacular languages still spoken in the group. But, alongside this indigenous name, there are many foreign place names, the perduring traces of the movement of early European voyagers: Espiritu Santo ± the contraction of Terra Austrialia del Espiritu Santo, the name given by Quirós in 1606;2 Pentecost ± the Anglicisation of Île de Pentecôte, conferred by Bougainville, who sighted this island on Whitsunday, 22 May 1768; Malakula, Erromango and Tanna ± the contemporary spellings of the Mallicollo, Erromanga and Tanna conferred by Cook who named the archipelago the New Hebrides in 1774, a name which, for foreigners at least, lasted from that date till 1980.3 Fortunately, some of these foreign names proved more ephemeral: the island we now know as Ambae, Bougainville called Île des Lepreux (Isle of Lepers), apparently because he mistook the pandemic skin conditions of tinea imbricata or leucodermia for signs of leprosy. -

0 Lunar and Planetary Institute Provided by the NASA Astrophysics Data System Mare Sereni Tatis Young, R.A

EVIDENCE FOR A SHALLOW REGIONAL SUBSURFACE DISCOt4TIN- UITY IN SOUTHERN MARE SERENITATIS. R.A. Young, Department of Geological Sciences, SUNY, Geneseo, N.Y. 14454. Several characteristics of south-central Mare Sereni tatis are unique to this basin and indicate that an unusual history may be recorded in the basin fill. Geologic evidence strongly supports a regional discontinuity beginning at depths greater than 40 m below the surface and extending to 250 m depths in some places. The following observations concerning the basin are pertinent to the discussion which follows: 1) The central porti on of Sereni tatis (brownish gray 1avas) represents much younger flooding than that which produced the older flows which ring the basin and form the highly cratered darker annulus of bluish gray lavas and mantling materials. A1 though the brownish gray lavas are approximately equivalent in age to large portions of the Imbrium basin surface (crater counts), most of the mare ridges in Sereni tatis experienced much 1ater growth and deforma- tion as demonstrated by their very sharp morphology and the un- usually large number of postmare craters filled by flows along the ridge flanks. 2) Despite the obvious 2-stage flooding of the basin there are few remnants of old flooded craters or ring structures, indicating either that the late stage filling was relatively deep or that some other deposit covered the surface before the most recent flooding. 3) The overturned strata in the rim flap of Bessel have exposed the bluish gray lavas found beneath the younger brownish gray surface rocks (1). The low depth/diameter ratio for Bessel (0.11) indicates that the con- tact zone must lie at a depth considerably shallower than the 1000 m depth of the crater floor below the surrounding surface. -

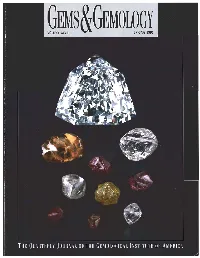

Spring 1991 Gems & Gemology

VOLUMEGEMS&GEMOLOGY XXVll SPRING 1991 SPRING 1991 Volume 27 No. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 The International Gemological Symposium: Facing the Future with GIA William E. Boyajian 2 Age, Origin, and Emplacement of Diamonds: Scientific Advances in the Last Decade Melissa B. IZirlzley, Iohn I. Gzlrney, and Alfred A. Levinson 26 Emeralds of the Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan Gary Bowersox, Lawrence W Snee, Eugene E. Foord, and Robert R. Seal II REGULARFEATURES 40 Gem Trade Lab Notes 46 Gem News 57 The Most Valuable Article Award and a New Look for Gems & Gemology I 59 Gems & Gemology Challenge - 61 Gemological Abstracts SPECIALSECTION: THE INTERNATIONAL GEMOLOGICALSYMPOSIUM Introduction 1 Abstracts of Feature Presentations 15 Panels and Panelists 17 Poster Session-A Marketplace of New Ideas ABOUT THE COVER: Diamonds are the heart of the jewelry industry Of critical importance is the continued supply of fine diamonds from the mines into the n~arlzetplace.The article on recenl research into the age, origin, and emplacement - of diamonds featured ~n this issue reviews new developments thul will be useful in the exploration and mining of diamonds for yeors to come. It cojncjdes with 1 the celebration of CIA'S diamond anniversary-60 years of service to the jewelry indrrstry In fi~tingtribute, this 89.01-ct D-internally flawless modified shield cut- the Guinea Star-sits above a group of fine rough diamonds that range from 0.74-12.76 ct. The faceted diamond is courtesy of William Goldberg Diamond Corp., New York; the other dicrmonds are courtesy of Cora Dinmond Corp., New York. Photo by Shone McClure. -

Nature. Vol. VI, No. 139 June 27, 1872

Nature. Vol. VI, No. 139 June 27, 1872 London: Macmillan Journals, June 27, 1872 https://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/LBXITYVRTMAPI83 Based on date of publication, this material is presumed to be in the public domain. For information on re-use, see: http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/Copyright The libraries provide public access to a wide range of material, including online exhibits, digitized collections, archival finding aids, our catalog, online articles, and a growing range of materials in many media. When possible, we provide rights information in catalog records, finding aids, and other metadata that accompanies collections or items. However, it is always the user's obligation to evaluate copyright and rights issues in light of their own use. 728 State Street | Madison, Wisconsin 53706 | library.wisc.edu NATURE — 157 The Committee has made three reports, namely, in THURSDAY, JUNE 27, 1872 1868, 1870, and 1871, the two first prepared by Sir W. Thomson, and the third by Mr. E. Roberts of the Nauti- | cal Alliance Office, under whose able superintendence the computations and deductions were placed. The ; three reports have been published zz eafenso by the THE TIDES AND THE TREASURY British Association in the volumes of the above-mentioned UR readers may have heard that England is a “sea- | years. They bring fully under view the theoretical basis O girt isle,” and that we are a maritime nation, pos- | of the investigation, an account of observations made by sessing a very powerful navy and an extensive commerce, | the Committee and by the authorities, some of the con- They also know that the ocean to which we owe these | clusions deduced therefrom, and a statement of the mea- peculiarities is a very restless fluid, its surface being ruffled | sures recommended in order to extend and perfect our by the wind, and its entire mass uplifted and depressed knowledge of the subject. -

Cult and Culture: American Dreams in Vanuatu1

PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. IV, No. 2 Spring 1981 CULT AND CULTURE: AMERICAN DREAMS IN VANUATU1 by Monty Lindstrom During the recent and troubled independence of Vanuatu, marred by se- cessionist attempts on two of its islands (Tanna and Santo), an “American connection” attracted international attention. This connection consisted of an idealized conception of America entertained by certain ni-Vanuatu (people of Vanuatu) and of a number of links between political organiza- tions in both countries, A singular concept of America as supreme source of Western material goods, knowledge and power, for example, has been a basic tenet of the John Frum Movement on the island of Tanna. John Frum, unusual for its longevity among South Pacific social movements, is one of those phenomena generally described as “cargo cults” (Worsley 1968, Burridge 1969). One of the factors sustaining the John Frum cult during the past forty years is the special relationship it claims with the United States. This relationship originated in a Tannese-American inter- action during 1942 to 1946 when the United States government estab- lished large military supply bases in the New Hebrides. The John Frum cult has evolved over the years through a number of organizational and ideological phases. The most recent of these was the participation by cult members in a revolt during May and June 1980 against the soon-to-be independent government of Vanuatu. This seces- sionist attempt on Tanna, and a companion one on the northern island Santo by members of a second organization called Nagriamel, received at 1Vanuatu, once the New Hebrides, achieved its independence on 30 July 1980. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

New Technologies and Language Shifting in Vanuatu

Pragmatics 23:1.169-179 (2013) International Pragmatics Association DOI: 10.1075/prag.23.1.08van NEW TECHNOLOGIES AND LANGUAGE SHIFTING IN VANUATU Leslie Vandeputte-Tavo Abstract During the last few years, mobile phones and social networks have deeply changed relationships and, insidiously, the use and representations of languages in Vanuatu. In spite of being very recent, it seems that new ways of communication imply changes regarding the various ways of using and adapting languages, amongst which are code-switching and language-shifting. Bislama, the national local lingua franca, is becoming more and more used in phone conversations. Internet and especially social networks (such as Facebook) are revealing new language strategies in social intercourses. This article examines interactions of languages that are mediated through social networks and mobile phone exchanges. More specifically, this paper discusses different language ideologies that are manifest in and deployed over forms of telecommunication. Keywords: Bislama; Pidgin; Ethnolinguistics; Mass media; Telecommunication; Linguistic ideology; Port-Vila; Vanuatu. 1. Introduction As many other small Pacific countries, Vanuatu has recently been the theater of an important telecommunication (mobiles, Internet) “revolution” which is currently still in progress. During the last few years, mobile phones and social networks (an Internet- based media program to make connections), have deeply changed social relationships and, insidiously, the use and representations of languages in Vanuatu. Digicel, the most important international telecommunication operator, arrived in Vanuatu in June 2008, giving Melanesians an easy access to mobile phones while experiencing its facilities and pernicious effects at the same time. The service is now available to over 80 percent of the population and « more and more ni-Vanuatu move to embrace the Digicel age1. -

Festschrift for Liz Pearce

School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies Linguistic travels in time and space: Festschrift for Liz Pearce Wellington Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 23, 2017 School33 of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies Linguistic travels in time and space: Festschrift for Liz Pearce Wellington Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 23, 2017 ISSN 1170-1978 (Print) ISSN 2230-4681 (Online) Linguistic travels in time and space: Festschrift for Liz Pearce Wellington Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 23, 2017 Edited by Heidi Quinn, Diane Massam, and Lisa Matthewson School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies Victoria University of Wellington P.O. Box 600 Wellington New Zealand Published 2017 Front cover image: Globe Master 3D, shared under CC-BY 3.0 license, http://en.globalquiz.org/quiz-image/indonesia-space-view/ Back cover photo: Diane Massam ISSN 1170-1978 (Print) ISSN 2230-4681 (Online) Linguistic travels in time and space: Festschrift for Liz Pearce Wellington Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 23, 2017 CONTENTS Editorial note Tabula congratulatoria Laurie Bauer How can you put Liz into a tree? 1 Sigrid Beck An alternative semantic cycle for universal 5 quantifiers Adriana Belletti Passive and movement of verbal chunks in a 15 V/head-movement language Guglielmo Cinque A note on Romance and Germanic past participle 19 relative clauses Nicola Daly and Julie Barbour Teachers’ understandings of the role of 29 translation in vernacular language maintenance in Malekula: some early thoughts William D. Davies Untangling multiple Madurese benefactives 35 Paul de Lacy Circumscriptive haplologizing reduplicants 41 Mark Hale Phonetics, phonology and syntax in synchrony 53 and diachrony Hans Henrich Hock Indo-European linguistics meets Micronesian and 63 Sunda-Sulawesi Leina Isno Nembangahu – The big stone 69 Richard S. -

Kimberlite-Hosted Diamond Deposits of Southern Africa: a Review Ore

Ore Geology Reviews 34 (2008) 33–75 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ore Geology Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/oregeorev Kimberlite-hosted diamond deposits of southern Africa: A review Matthew Field a,⁎, Johann Stiefenhofer b, Jock Robey c, Stephan Kurszlaukis d a DiaKim Consulting Limited, Mayfield, Wells Road, Wookey Hole Wells, Somerset, BA5 1DN, United Kingdom b De Beers Group Services (Pty) Limited, Mineral Resource Management, P.O. Box 82851, Southdale, 2135, South Africa c De Beers Group Services, PO Box 47, Kimberley, South Africa d De Beers Canada Inc. 65 Overlea Boulevard, Toronto, Ontario, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Following the discovery of diamonds in river deposits in central South Africa in the mid nineteenth century, it Received 21 November 2006 was at Kimberley where the volcanic origin of diamonds was first recognized. These volcanic rocks, that were Accepted 4 November 2007 named “kimberlite”, were to become the corner stone of the economic and industrial development of Available online 22 April 2008 southern Africa. Following the discoveries at Kimberley, even more valuable deposits were discovered in South Africa and Botswana in particular, but also in Lesotho, Swaziland and Zimbabwe. Keywords: A century of study of kimberlites, and the diamonds and other mantle-derived rocks they contain, has Diamond Kimberlite furthered the understanding of the processes that occurred within the sub-continental lithosphere and in Diatreme particular the formation of diamonds. The formation of kimberlite-hosted diamond deposits is a long-lived Pipe and complex series of processes that first involved the growth of diamonds in the mantle, and later their Dyke removal and transport to the earth's surface by kimberlite magmas. -

Downloaded From: Books at JSTOR, EBSCO, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, OAPEN, Project MUSE, and Many Other Open Repositories

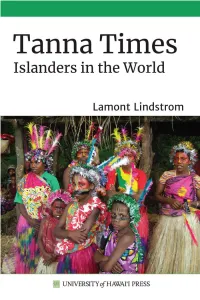

Tanna Times Islanders in the World • Lamont Lindstrom ‘ © University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Cover photo: Women and girls at a boy’s circumcision exchange, Ikurup village, . Photo by the author. is book is published as part of the Sustainable History Monograph Pilot. With the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Pilot uses cutting-edge publishing technology to produce open access digital editions of high-quality, peer-reviewed monographs from leading university presses. Free digital editions can be downloaded from: Books at JSTOR, EBSCO, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, OAPEN, Project MUSE, and many other open repositories. While the digital edition is free to download, read, and share, the book is under copyright and covered by the following Creative Commons License: CC BY-NC-ND. Please consult www.creativecommons.org if you have questions about your rights to reuse the material in this book. When you cite the book, please include the following URL for its Digital Object Identier (DOI): https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle// We are eager to learn more about how you discovered this title and how you are using it. We hope you will spend a few minutes answering a couple of questions at this url: https://www.longleafservices.org/shmp-survey/ More information about the Sustainable History Monograph Pilot can be found at https://www.longleafservices.org. for Katiri, Maui, and Nora Rika • Woe to those who are at ease in Zion and to those who feel secure on the mountain of Samaria.