Identification Key : Unique Criterion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Literature Review

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1. BASIDIOMYCOTA (MACROFUNGI) Representatives of the fungi sensu stricto include four phyla: Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota and Zygomycota (McLaughlin et al., 2001; Seifert and Gams, 2001). Chytridiomycota and Zygomycota are described as lower fungi. They are characterized by vegetative mycelium with no septa, complete septa are only found in reproductive structures. Asexual and sexual reproductions are by sporangia and zygospore formation respectively. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are higher fungi and have a more complex mycelium with elaborate, perforate septa. Members of Ascomycota produce sexual ascospores in sac-shaped cells (asci) while fungi in Basidiomycota produce sexual basidiospores on club-shaped basidia in complex fruit bodies. Anamorphic fungi are anamorphs of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota and usually produce asexual conidia (Nicklin et al., 1999; Kirk et al., 2001). The Basidiomycota contains about 30,000 described species, which is 37% of the described species of true Fungi (Kirk et al., 2001). They have a huge impact on human affairs and ecosystem functioning. Many Basidiomycota obtain nutrition by decaying dead organic matter, including wood and leaf litter. Thus, Basidiomycota play a significant role in the carbon cycle. Unfortunately, Basidiomycota frequently 5 attack the wood in buildings and other structures, which has negative economic consequences for humans. 2.1.1 LIFE CYCLE OF MUSHROOM (BASIDIOMYCOTA) The life cycle of mushroom (Figure 2.1) is beginning at the site of meiosis. The basidium is the cell in which karyogamy (nuclear fusion) and meiosis occur, and on which haploid basidiospores are formed (basidia are not produced by asexual Basidiomycota). Mushroom produce basidia on multicellular fruiting bodies. -

Study on Species of Phylloporus I: Neotropics and North America

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/45279837 Study on species of Phylloporus I: Neotropics and North America Article in Mycologia · July 2010 DOI: 10.3852/09-215 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 11 203 2 authors: Maria Alice Neves Roy E Halling Federal University of Santa Catarina New York Botanical Garden 72 PUBLICATIONS 297 CITATIONS 141 PUBLICATIONS 1,496 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Boletinae of Australia View project Diversity and systematics of South-East Asian Boletineae View project All content following this page was uploaded by Roy E Halling on 29 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Mycologia, 102(4), 2010, pp. 923–943. DOI: 10.3852/09-215 # 2010 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Study on species of Phylloporus I: Neotropics and North America Maria Alice Neves1 (Halling 1989, Orijel-Garibay et al. 2008, Osmundson Departamento de Sistema´tica e Ecologia, Campus 1, et al. 2007). In Belize these forests occur at lower Universidade Federal da Paraı´ba, Cidade elevation, where members of the Boletaceae also are Universita´ria, Joa˜o Pessoa, PB, 58051-970, Brazil present and associated with these hosts (Ortiz- Roy E. Halling Santana et al. 2007). In Guyana species of Boletaceae Institute of Systematic Botany, The New York Botanical have been associated with Dicymbe species (Henkel et Garden, Bronx, New York, 10458-5126 al. 2002). Some of the areas that need more attention are the lowlands of central Amazonia, where Singer et al. -

MUSHROOMS of the OTTAWA NATIONAL FOREST Compiled By

MUSHROOMS OF THE OTTAWA NATIONAL FOREST Compiled by Dana L. Richter, School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI for Ottawa National Forest, Ironwood, MI March, 2011 Introduction There are many thousands of fungi in the Ottawa National Forest filling every possible niche imaginable. A remarkable feature of the fungi is that they are ubiquitous! The mushroom is the large spore-producing structure made by certain fungi. Only a relatively small number of all the fungi in the Ottawa forest ecosystem make mushrooms. Some are distinctive and easily identifiable, while others are cryptic and require microscopic and chemical analyses to accurately name. This is a list of some of the most common and obvious mushrooms that can be found in the Ottawa National Forest, including a few that are uncommon or relatively rare. The mushrooms considered here are within the phyla Ascomycetes – the morel and cup fungi, and Basidiomycetes – the toadstool and shelf-like fungi. There are perhaps 2000 to 3000 mushrooms in the Ottawa, and this is simply a guess, since many species have yet to be discovered or named. This number is based on lists of fungi compiled in areas such as the Huron Mountains of northern Michigan (Richter 2008) and in the state of Wisconsin (Parker 2006). The list contains 227 species from several authoritative sources and from the author’s experience teaching, studying and collecting mushrooms in the northern Great Lakes States for the past thirty years. Although comments on edibility of certain species are given, the author neither endorses nor encourages the eating of wild mushrooms except with extreme caution and with the awareness that some mushrooms may cause life-threatening illness or even death. -

Boletes from Belize and the Dominican Republic

Fungal Diversity Boletes from Belize and the Dominican Republic Beatriz Ortiz-Santana1*, D. Jean Lodge2, Timothy J. Baroni3 and Ernst E. Both4 1Center for Forest Mycology Research, Northern Research Station, USDA-FS, Forest Products Laboratory, One Gifford Pinchot Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53726-2398, USA 2Center for Forest Mycology Research, Northern Research Station, USDA-FS, PO Box 1377, Luquillo, Puerto Rico 00773-1377, USA 3Department of Biological Sciences, PO Box 2000, SUNY-College at Cortland, Cortland, New York 13045, USA 4Buffalo Museum of Science, 1020 Humboldt Parkway, Buffalo, New York 14211, USA Ortiz-Santana, B., Lodge, D.J., Baroni, T.J. and Both, E.E. (2007). Boletes from Belize and the Dominican Republic. Fungal Diversity 27: 247-416. This paper presents results of surveys of stipitate-pileate Boletales in Belize and the Dominican Republic. A key to the Boletales from Belize and the Dominican Republic is provided, followed by descriptions, drawings of the micro-structures and photographs of each identified species. Approximately 456 collections from Belize and 222 from the Dominican Republic were studied comprising 58 species of boletes, greatly augmenting the knowledge of the diversity of this group in the Caribbean Basin. A total of 52 species in 14 genera were identified from Belize, including 14 new species. Twenty-nine of the previously described species are new records for Belize and 11 are new for Central America. In the Dominican Republic, 14 species in 7 genera were found, including 4 new species, with one of these new species also occurring in Belize, i.e. Retiboletus vinaceipes. Only one of the previously described species found in the Dominican Republic is a new record for Hispaniola and the Caribbean. -

How to Distinguish Amanita Smithiana from Matsutake and Catathelasma Species

VOLUME 57: 1 JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2017 www.namyco.org How to Distinguish Amanita smithiana from Matsutake and Catathelasma species By Michael W. Beug: Chair, NAMA Toxicology Committee A recent rash of mushroom poisonings involving liver failure in Oregon prompted Michael Beug to issue the following photos and information on distinguishing the differences between the toxic Amanita smithiana and edible Matsutake and Catathelasma. Distinguishing the choice edible Amanita smithiana Amanita smithiana Matsutake (Tricholoma magnivelare) from the highly poisonous Amanita smithiana is best done by laying the stipe (stem) of the mushroom in the palm of your hand and then squeezing down on the stipe with your thumb, applying as much pressure as you can. Amanita smithiana is very firm but if you squeeze hard, the stipe will shatter. Matsutake The stipe of the Matsutake is much denser and will not shatter (unless it is riddled with insect larvae and is no longer in good edible condition). There are other important differences. The flesh of Matsutake peels or shreds like string cheese. Also, the stipe of the Matsutake is widest near the gills Matsutake and tapers gradually to a point while the stipe of Amanita smithiana tends to be bulbous and is usually widest right at ground level. The partial veil and ring of a Matsutake is membranous while the partial veil and ring of Amanita smithiana is powdery and readily flocculates into small pieces (often disappearing entirely). For most people the difference in odor is very distinctive. Most collections of Amanita smithiana have a bleach-like odor while Matsutake has a distinctive smell of old gym socks and cinnamon redhots (however, not all people can distinguish the odors). -

The Phylogeny of Selected Phylloporus Species, Inferred from NUC-LSU and ITS Sequences, and Descriptions of New Species from the Old World

The phylogeny of selected Phylloporus species, inferred from NUC-LSU and ITS sequences, and descriptions of new species from the Old World Maria Alice Neves, Manfred Binder, Roy Halling, David Hibbett & Kasem Soytong Fungal Diversity An International Journal of Mycology ISSN 1560-2745 Fungal Diversity DOI 10.1007/s13225-012-0154-0 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by The Mushroom Research Foundation. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy Fungal Diversity DOI 10.1007/s13225-012-0154-0 The phylogeny of selected Phylloporus species, inferred from NUC-LSU and ITS sequences, and descriptions of new species from the Old World Maria Alice Neves & Manfred Binder & Roy Halling & David Hibbett & Kasem Soytong Received: 12 November 2011 /Accepted: 11 January 2012 # The Mushroom Research Foundation 2012 Abstract The phylogeny of Phylloporus (Boletaceae) has of Phylloporus and includes 20 species from different not been well studied, and the taxonomic relationships of geographic regions. Six taxa of Phylloporus from the this genus have varied considerably among authors. The OldWorldareherepresented.Phylloporus cyanescens following study presents phylogenetic relationships of is a new combination for an Australasian taxon formerly Phylloporus based on two nuclear ribosomal DNA named as a variety of P. -

Fungus Among Us: Antrim As Mushroom Paradise George Caughey to Paraphrase Charles Dickens, 2018 Was the Worst of Going to See Every Kind of Mushroom Every Year

Fungus Among Us: Antrim as Mushroom Paradise George Caughey To paraphrase Charles Dickens, 2018 was the worst of going to see every kind of mushroom every year. That will times and then the best of times—fungally speaking—but depend on conditions and luck, and some varieties are rarely allow me to provide a bit of background before explaining encountered. Just because you don’t see a particular mush- further. room doesn’t mean it isn’t there, for much of the year most The fact that Antrim is mycologically blessed is not near- types lurk largely unseen as mycelium—the white, stringy ly as well-known as it could or should be. The same variety or cottony material you see inside a log or under a mat of of soils, exposures, drainage conditions and habitats—our leaves. Some years, if conditions are not right, the fungus, swamps, floodplains, pastures, shrubland, mature forest and although very much alive, may opt not to send up spore-pro- mountain balds, which support a range of wildlife and a par- ducing fruiting bodies at all, but just wait for better times. ticularly rich mix of plants and trees—also enable growth In 2018, by mid-summer, for many Antrim fungi, the time of many different types of fungi. Like most living things, was right. mushrooms and other varieties of fungi can be very particu- The late Spring and early Summer mushroom season lar about when and where they will grow. Many of the big started inauspiciously, with June and much of July being un- fleshy mushrooms that are familiar to anyone who walks our seasonably dry, despite occasional torrential downpours— woods grow in association with the roots of selected living not great conditions for fruiting. -

<I>Xerocomus Porophyllus</I>

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2013. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/124.255 Volume 124, pp. 255–262 April–June 2013 Xerocomus porophyllus sp. nov., morphologically intermediate between Phylloporus and Xerocomus Wen-Juan Yan, Tai-Hui Li *, Ming Zhang & Ting Li State Key Laboratory of Applied Microbiology, South China (The Ministry—Province Joint Development), Guangdong Institute of Microbiology, Guangzhou 510070, Guangdong, China *Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract— Xerocomus porophyllus, discovered from Dinghushan Biosphere Reserve in Guangdong province (southern China), is described as a new species. It is a morphologically intermediate taxon between Phylloporus and Xerocomus since its hymenophore is lamellate around the stipe but strongly anastomosing to distinctly faveolate or poroid towards pileus margin. Molecular analyses of nuclear rDNA ITS and LSU sequences, however, indicate that it has a closer genetic relationship with Xerocomus than with Phylloporus. Key words— Basidiomycota, Boletaceae, Boletales, phylogeny, taxonomy Introduction Phylloporus Quél. and Xerocomus Quél. belong to the family Boletaceae and have a close relationship, whether Phylloporus has been considered as a primitive group in the family (Corner 1972) or as a derived genus next to Xerocomus (Binder 1999; Binder & Hibbett 2006). Molecular data have shown the Xerocomus subtomentosus complex to be closely related to Phylloporus (Binder 1999). The lamellate hymenophore inPhylloporus and the wide poroid or tubular one in Xerocomus are still used as the main morphological characters for differentiating the two genera (Neves & Halling 2010; Neves et al. 2012). Worldwide, Phylloporus encompasses about 70 named species (Neves et al. 2012), 21 of which have been reported from China (Teng 1963; Zang & Zeng 1978; Li et al. -

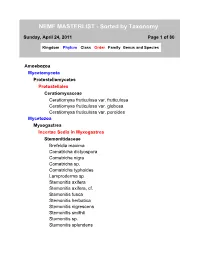

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy Sunday, April 24, 2011 Page 1 of 80 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus and Species Amoebozoa Mycetomycota Protosteliomycetes Protosteliales Ceratiomyxaceae Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. globosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. poroides Mycetozoa Myxogastrea Incertae Sedis in Myxogastrea Stemonitidaceae Brefeldia maxima Comatricha dictyospora Comatricha nigra Comatricha sp. Comatricha typhoides Lamproderma sp. Stemonitis axifera Stemonitis axifera, cf. Stemonitis fusca Stemonitis herbatica Stemonitis nigrescens Stemonitis smithii Stemonitis sp. Stemonitis splendens Fungus Ascomycota Ascomycetes Boliniales Boliniaceae Camarops petersii Capnodiales Capnodiaceae Capnodium tiliae Diaporthales Valsaceae Cryphonectria parasitica Valsaria peckii Elaphomycetales Elaphomycetaceae Elaphomyces granulatus Elaphomyces muricatus Elaphomyces sp. Erysiphales Erysiphaceae Erysiphe polygoni Microsphaera alni Microsphaera alphitoides Microsphaera penicillata Uncinula sp. Halosphaeriales Halosphaeriaceae Cerioporiopsis pannocintus Hysteriales Hysteriaceae Glonium stellatum Hysterium angustatum Micothyriales Microthyriaceae Microthyrium sp. Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Phaeocalicium polyporaeum Ostropales Graphidaceae Graphis scripta Stictidaceae Cryptodiscus sp. 1 Peltigerales Collemataceae Leptogium cyanescens Peltigeraceae Peltigera canina Peltigera evansiana Peltigera horizontalis Peltigera membranacea Peltigera praetextala Pertusariales Icmadophilaceae Dibaeis baeomyces Pezizales -

FUNGI of the SAND PRAIRIE-SCRUB OAK NATURE PRESERVE Illinois Nongame Wildlife Conservation Fund 1993-1994 Small Project Program Report

0 FUNGI OF THE SAND PRAIRIE-SCRUB OAK NATURE PRESERVE Illinois Nongame Wildlife Conservation Fund 1993-1994 Small Project Program Report August 10, 1994 0 Dr . Andrew S . Methven Botany Department . Eastern Illinois University Charleston, IL 61920 Introduction The vegetation found in the Sand Prairie-Scrub Oak Nature Preserve (nine miles south of Havana, between Bath and Kilbourne, Sec . 23 and parts of Secs . 14 and 26, T20N, R9W', 3PM, Mason Co) is a mosaic of three unique vascular plant communities - sand prairie, savanna, and closed forest . The closed forests in the preserve are dominated by a stable community of shade intolerant trees including black oak (Quercus velutina), blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica), black hickory, (Carya texana), and mockernut hickory (Carya tanentosa) which thrive under xeric conditions in acidic, sandy soils . Despite the number of floristic and ecological studies completed to date on these closed forests, there has been little effort to catalog the fungi which occur in these habitats and assess their ecological role in the maintenance and preservation of the forest . Although the importance of saprobic fungi as agents of decomposition and nutrient recycling is well-established, the role of fungi as mycorrhizal associates with vascular plants has only recently begun to be assessed and understood . Mycorrhizae are unique symbiotic associations which form between fungal hyphae and the roots of vascular plants . Since the fungal hyphae penetrate the soil to a mach greater extent than roots, they have a greater surface area in contact with soil moisture and nutrients than vascular plants . As such, the fungal hyphae facilitate the uptake of water and nutrients from the soil and transport to the plant host . -

Sporeprint, Winter 2002

LONG ISLAND MYCOLOGICAL CLUB VOLUME 10, NUMBER 4, WINTER, 2002 CHAMPIGNONS, CHATEAUS, AND CAMEMBERT FINDINGS AFIELD by George Davis by Joel Horman ll mushroomers In early October Karen and I accompanied members of the Long seem to have a par- A Island and New York mushroom clubs on a delightful mushroom tour of ticular fondness for boletes. France. The tour was organized by Claudine Michaud and Jacques Bro- Whether it is their unique stat- chard, members of both the LIMC and NYMS. We started in Paris with ure, their almost universal edi- a memorable evening of feasting and singing. bility, their vivid and evanescent coloration reactions, or their lim- ited seasonality- or all of the above- is a moot question. The fact that we continue to docu- ment previously unrecorded spe- cies in our area is another point in their favor. Moreover, we have a better chance of identifying such a visitant -thanks to the species keys and color photos of, " North American Boletes" by Alan Bessette, William Roody, and Ar- leen Bessette- than of, say, an errant species of Inocybe or Corti- narius. LIMC members: Jacques Brochard (kneeling,left),Claudine Michaud (Rt., & husband Henri, last row, Rt); George & Karen Davis (3rd & 4th from Rt.) with NYMS members. Next day we traveled by train and bus to Lavaveix-les-Mines in the Limousin region. There we were featured guests for their “Mushroom Celebration”, which began with forays led by the local mushroom club members including many pharmacists. (In France phar- macists are required to take two years of mycology courses and identify edible mushrooms for the public.) The collected mushrooms were identi- fied and organized into a large display similar to those found at NEMF or NAMA forays. -

A Sequence Database for the Identification of Ectomycorrhizal Basidiomycetes by Phylogenetic Analysis

Molecular Ecology (1998) 7, 257–272 A sequence database for the identification of ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes by phylogenetic analysis T. D. BRUNS,* T. M. SZARO,* M. GARDES,† K. W. CULLINGS,‡ J. J. PAN,§ D. L. TAYLOR,** T. R. HORTON,†† A. KRETZER,‡‡ M. GARBELOTTO,* and Y. LI§§ *Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California, Berkeley, 94720–3102, USA, †CESAC/CNRS, Université Paul Sabatier/Toulouse III, 29 rue Jeanne Marvig, 31055 Toulouse Cedex 4, France, ‡NASA-Ames Research Center, MS-239-4, Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000, §Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington IN 47405, USA, **Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA, ††USDA Forest Service, Forest Science Laboratory, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA, ‡‡Dept of Botany and Plant Pathology, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA, §§Fox Chase Cancer Center, 7701 Burholme Ave, Philadelphia, PA19911, USA Abstract We have assembled a sequence database for 80 genera of Basidiomycota from the Hymenomycete lineage (sensu Swann & Taylor 1993) for a small region of the mitochon- drial large subunit rRNA gene. Our taxonomic sample is highly biased toward known ectomycorrhizal (EM) taxa, but also includes some related saprobic species. This gene fragment can be amplified directly from mycorrhizae, sequenced, and used to determine the family or subfamily of many unknown mycorrhizal basidiomycetes. The method is robust to minor sequencing errors, minor misalignments, and method of phylogenetic analysis. Evolutionary inferences are limited by the small size and conservative nature of the gene fragment. Nevertheless two interesting patterns emerge: (i) the switch between ectomycorrhizae and saprobic lifestyles appears to have happened convergently several and perhaps many times; and (ii) at least five independent lineages of ectomycorrhizal fungi are characterized by very short branch lengths.