Honji Suijaku Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Japan Redux 3

Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG February 2017 The cover painting is a section from 弱竹物語, National Diet Library. Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG, February 2017 Content Poem and Stories The Origins of Japan ……………………………………………… April Grace Petrascu 2 Journal of an Unnamed Samurai ………………………………… Myles Kristalovich 5 Holdout at Yoshino ……………………………………………………… Zachary Adrian 8 Memoirs of Ieyasu ……………………………………………………………… Selena Yu 12 Sword Tales ………………………………………………………………… Adam Cohen 15 Comics Creation of Japan …………………………………………………………… Karla Montilla 19 Yoshitsune & Benkei ………………………………………………………… Alicia Phan 34 The Story of Ashikaga Couple, others …………………… Qianhua Chen, Rui Yan 44 This is a collection of poem, stories and manga comics from the final reports submitted to Japanese Civilization, fall 2016. Please enjoy the young creativity and imagination! P a g e | 2 The Origins of Japan The Mythical History April Grace Petrascu At the beginning Izanagi and Izanami descended The universe was chaos Upon these islands The heavens and earth And began to wander them Just existed side by side Separately, the first time Like a yolk inside an egg When they met again, When heaven rose up Izanami called to him: The kami began to form “How lovely to see Four pairs of beings A man such as yourself here!” After two of genesis The first-time speech was ever used. Creating the shape of earth The male god, upset Izanagi, male That the first use of the tongue Izanami, the female Was used carelessly, Kami divided He once again circled the land By their gender, the only In an attempt to cool down Kami pair to be split so Once they met again, Both of these two gods Izanagi called to her: Emerged from heaven wanting “How lovely to see To build their own thing A woman like yourself here!” Upon the surface of earth The first time their love was matched. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What Is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura This ritual dance is performed to purify the kagura site, with the performer carrying a Since ancient times, people in Japan have believed torimono (prop) while remaining unmasked. Various props are carried while the dance is that gods inhabit everything in nature such as rocks and History of Izumo Kagura Shichiza performed without wearing any masks. The name shichiza is said to derive from the seven trees. Human beings embodied spirits that resonated The Shimane Prefecture is a region which boasts performance steps that comprise it, but these steps vary by region. and sympathized with nature, thus treasured its a flourishing, nationally renowned kagura scene, aesthetic beauty. with over 200 kagura groups currently active in the The word kagura is believed to refer to festive prefecture. Within Shimane Prefecture, the regions of rituals carried out at kamikura (the seats of gods), Izumo, Iwami, and Oki have their own unique style of and its meaning suggests a “place for calling out and kagura. calming of the gods.” The theory posits that the word Kagura of the Izumo region, known as Izumo kamikuragoto (activity for the seats of gods) was Kagura, is best characterized by three parts: shichiza, shortened to kankura, which subsequently became shikisanba, and shinno. kagura. Shihoken Salt—signifying cleanliness—is used In the first stage, four dancers hold bells and hei (staffs with Shiokiyome paper streamers), followed by swords in the second stage of Sada Shinno (a UNESCO Intangible Cultural (Salt Purification) to purify the site and the attendees. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Amaterasu - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

אמאטרסו أماتيراسو آماتراسو Amaterasu - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amaterasu Amaterasu From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Amaterasu (天照 ), Amaterasu- ōmikami (天照大 神/天照大御神 ) or Ōhirume-no-muchi-no-kami (大日孁貴神 ) is a part of the Japanese myth cycle and also a major deity of the Shinto religion. She is the goddess of the sun, but also of the universe. The name Amaterasu derived from Amateru meaning "shining in heaven." The meaning of her whole name, Amaterasu- ōmikami, is "the great august kami (god) who shines in the heaven". [N 1] Based on the mythological stories in Kojiki and Nihon Shoki , The Sun goddess emerging out of a cave, bringing sunlight the Emperors of Japan are considered to be direct back to the universe descendants of Amaterasu. Look up amaterasu in Wiktionary, the free Contents dictionary. 1 History 2 Worship 3 In popular culture 4 See also 5 Notes 6 References History The oldest tales of Amaterasu come from the ca. 680 AD Kojiki and ca. 720 AD Nihon Shoki , the oldest records of Japanese history. In Japanese mythology, Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun, is the sister of Susanoo, the god of storms and the sea, and of Tsukuyomi, the god of the moon. It was written that Amaterasu had painted the landscape with her siblings to create ancient Japan. All three were born from Izanagi, when he was purifying himself after entering Yomi, the underworld, after failing to save Izanami. Amaterasu was born when Izanagi washed out his left eye, Tsukuyomi was born from the washing of the right eye, and Susanoo from the washing of the nose. -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

The Making of an American Shinto Community

THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN SHINTO COMMUNITY By SARAH SPAID ISHIDA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2007 Sarah Spaid Ishida 2 To my brother, Travis 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people assisted in the production of this project. I would like to express my thanks to the many wonderful professors who I have learned from both at Wittenberg University and at the University of Florida, specifically the members of my thesis committee, Dr. Mario Poceski and Dr. Jason Neelis. For their time, advice and assistance, I would like to thank Dr. Travis Smith, Dr. Manuel Vásquez, Eleanor Finnegan, and Phillip Green. I would also like to thank Annie Newman for her continued help and efforts, David Hickey who assisted me in my research, and Paul Gomes III of the University of Hawai’i for volunteering his research to me. Additionally I want to thank all of my friends at the University of Florida and my husband, Kyohei, for their companionship, understanding, and late-night counseling. Lastly and most importantly, I would like to extend a sincere thanks to the Shinto community of the Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America and Reverend Koichi Barrish. Without them, this would not have been possible. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT.....................................................................................................................................7 -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

The Hachiman Cult and the Dokyo Incident Author(S): Ross Bender Source: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol

The Hachiman Cult and the Dokyo Incident Author(s): Ross Bender Source: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Summer, 1979), pp. 125-153 Published by: Sophia University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2384320 Accessed: 17-03-2016 17:03 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Sophia University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Monumenta Nipponica. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 77.80.42.241 on Thu, 17 Mar 2016 17:03:08 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Hachiman Cult and the D6ky6 Incident by Ross BENDER XO I NE of the gravest assaults ever made on the Japanese imperial institution was launched by the Buddhist priest D6ky6' in the 760s. Dokyo, who came from a clan of the low-ranking provincial aristocracy, gained the affection of the retired Empress K6ken2 in 761 and proceeded to gather political power to himself; by the end of the decade he stood as the paramount figure in the court bureaucracy and had already begun to usurp imperial prerogatives. It was in 769 that an oracle from the shrine of Hachiman in Kyushu was reported to Nara: the god prophesied peace in the realm if Dokyo were proclaimed em- peror. -

Japanese Myths and Rituals

97 Association of the Sun and the Rice in Japanese Myths and Rituals Atsuhiko Yoshida Key words:myth, ritual, Shinto, Amaterasu, Izanagi, Mikuratananokami, Susanowo, Ukemochi, Tsukiyomi, Okuninushi, Hononinigi, Amenouzume, Toyouke, Tent6, Daij6sai, Ise, A Izumo, Takachiho, Tsushim3. Summary:The Sun-goddess Amaterasu, being the supreme deity of Shintδ, is closely associated also with the rice crop throughout the mythology as well as in her cult celebrated at the Inner and Outer Shrines of Ise. She even obviously shows some of the characteristic traits common to the rice deities of the East Asian rice cultivators. A similar tendency to connect a solar deity with the rice is found also in folk beliefs and lores all around Japan;one of the conspicuous examples being the Tent6 festival of the island of Tstlshima, in which a straw bag containing grains of a special kind of holy red rice is most solemnly reverenced as an incarnation of a solar deity. The most prominent figure of Japanese mythology is the resplendent Sun-goddess Amatera- su(Glorious-Shiner-of-Heaven). She is claimed to be the divine ancestress of the Imperial Family and to rule universe sovereignly and magnanimously from her realm, the Plain of High Heaven(Takamagahara), where eight millions of celestial deities submit themselves willingly to her command. According to one version of the myth, she is one of the three last born and noblest children of her divine father, Izanagi. This god was sent down in primor・ dial times from Heaven with his sister, the goddess Izanami, who became -

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

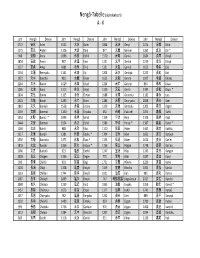

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō