Tactile Impression: the Reemergence of Craft Through Letterpress in a Typographic Design Curriculum by Assistant Professor J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printing in Isaiah Thomas's Time

Printing in Isaiah Thomas’s Time Printing in Isaiah Thomas’ time had changed very little since Johannes Gutenberg first printed his Bible in 1455. The press that Isaiah first learned to use was essentially the same type of press used for centuries. It was made of wood and called a block or blaeu style press. It was operated by hand and took an enormous amount of strength to pull the handle or bar that turned a large metal screw that in turn pressed a square block of stone down on the type to make an impression. Printers would develop the muscles on the side of their body with which they pulled on the press. This overdevelopment of these muscles made them walk and move with what was called a printer’s gait. It was possible for printers to recognize another printer by the way he moved down the street. 1 The printing process started by setting type. Every character, including all letters, punctuation marks, and even blank spaces, were made out of individual pieces of metal. These pieces of type were often called faces , which was short for typefaces . These pieces of type would be placed in wooden boxes divided into little partitions for each letter, punctuation mark, or space. Much like a contemporary computer keyboard, these type cases were arranged for easy and quick access to those partitions containing the letters that were used most frequently. Printers were careful to make sure the individual characters were separated and in their proper partitions. Type that was all mixed up was called a printer’s pie. -

The Museum of Printing History Offers Hands-On Learning Opportunities for Students of All Ages

Welcome The Museum of Printing History offers hands-on learning opportunities for students of all ages. Visits to the Museum are appropriate for a wide range of subjects, whether the focus is science and technology or English Language Arts, history or fine arts and crafts. With exhibitions dedicated to the development of essential technologies, American and Texas history, the traditions of Western literature and art – as well as working galleries for crafts such as papermaking, printmaking, and bookbinding – the visiting student will encounter scholars and artists who are gifted at bringing the past to life. Museum of Printing History tours are customizable to the needs of any class. Discuss a course or unit topic with our Curator or Artist-in-Residence to develop a tour which fits the subject matter that the students are currently exploring. If suitable for the size of your group, it is also possible to introduce hands-on projects, such as a session printing in our lithography studio with Houston artist Charles Criner, or an introduction to book construction and history with one of our bookbinders. In addition to regularly scheduled classes, the Museum of Printing History can work with your school or community group to schedule workshops on a wide range of topics relating to the art of the book. We have a list of workshops available on demand, or we may work together to design something special for your group. For questions, or to schedule your outreach workshop, please contact Amanda Stevenson, Curator, [email protected], 713-522-4652, ext. 207. Contents Preparing for your Visit Maps & Directions 2 Tour Information 3 Museum Overview 4 Pre-Visit Discussions 5 Museum & Post Visit Activities 11 1 Preparing for Your Visit Convenient to downtown and to all major freeways, the Museum is located at 1324 West Clay, between Waugh Drive and Montrose, just south of Allen Parkway. -

Principles of Typesetting

h e H T a p p y T PREPARE y p e s e t t 1. Determine the longest line to be set. Keep in mind that if lines are staggered left e r or right, your line must run the entire length from most left to most right. 2. To determine the length of leading to use: add at least 48pts to the line length (to give room for large spacing on the ends of each line) and round up to the nearest convenient furniture length. 3. Set up your work area. Pull your type tray out carefully and set it on one of the work counters. Set a good amount of the leading length and thickness that you’ve chosen next to the type tray. Check your leading to make sure it is all the same length (no oddballs). 4. Clear out the spacing compartments in your tray. The spacing in these trays are often a bit jumbled. Sort them out before you begin. 5. Retrieve some word-spacers, ems, and quads from the appropriate spacing drawer, and sort them into the appropriate compartments in your type tray. If necessary, you may want to pull out the spacing drawer and set it along-side your type tray. 6. Hold the composing stick so that your wrist is as straight and relaxed as possible. Have your thumb or forefinger poised to hold type as you set it in the stick. BEGIN SETTING 1. Lay in a piece of leading. If the leading is too long to fit easily, check the leading length and check the placement of the “stop” on the composing stick. -

Type-Composing Machines of the Past, the Present, and the Future

Type-Composing Machines of The Past, the Present, and the Future. A PAPER Read before the Balloon Society of Great Britain, at St. James’ Hall, October 3rd, 1890. by JOHN SOUTHWARD, Editor “Paper and Printing Trades Journal”; Author of “The Dictionary of Typography.”, “Practical Printing,” “The Principles and Progress of Printing Machinery” Article, “Typography” in “Encyclopaedia Britannica” and “Printing” in “Chambers’s Encyclopaedia” Examiner (1878) in Printing to City and Guilds of London Institute for the Advancement of Technical Education. [COPYRIGHT.] LEICESTER: RAITHBY, LAWRENCE & CO., LIMITED, DE MONTFORT PRESS, 1891. ADVERTISEMENT. The following Paper is given as it was originally written. Owing to shortness of time, some passages had to he omitted in the reading. THE visitor to the composing department of a printing office finds a number of operatives engaged upon a process that is, apparently, extremely monotonous and fatiguing. Standing before a pair of shallow wooden trays, known as cases, inclined desk-like, the compositor holds in his left hand what is called a composing-stick a little iron or brass frame, one side of which is movable, so that it may be adjusted to the required width of the page or column which the workman has to set up. The "copy" from which he works rests on the least-used part of the upper case. The practised compositor takes in several words at a glance provided the author writes an intelligible hand, which virtue is by no means universal. One by one, then, the compositor puts the letters of each word and sentence into his stick, securing each letter with the thumb of his left hand, which is, therefore continually travelling from the beginning to the end of the line. -

Letterpress Terms

Letterpress Terms GENERAL TERMS Type High – The height of type from it’s base to it’s printing surface. .918 of an inch or 15/16th. Letterpress – A traditional way of printing, where a plate with the image standing proud Type High Gauge – Tool for measuring if type of the surface is inked and then impressed is at the correct height. onto the paper. Traditionally, it was not correct to indent the paper but it has now become fashionable to do so. Printing Press - A device that applies pressure that transfers ink form a surface to a medium. They revolutionized mass communication, changed the course of history & today call back to simpler times. Put simply, they are magic. Platen Press– A press with a flat plate which is pressed against a medium (paper) to cause an impression. These have an inking disc up top and a large flywheel on one side. Pied Type – Type which is in a jumbled mess. Proofing Press – A press used to prep a print for production. The bed of this press is parallel to the ground and either a roller moves on top of the bed or the entire bed itself can move. Letterpress Terms SETTING A FORM California Job Case – method of organization of the letters in a case. is a kind of type case: a Form – what you set to print, composed of compartmentalized wooden box used to store letters and or images. movable type used in letterpress printing. It was the most popular and accepted of the job case designs in America. -

Typesetting Techniques

NBS MONOGRAPH 99 Automatic Typographic-Quality Typesetting Techniques: A State-of-the-Art Review U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS —— THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards ' provides measurement and technical information services essential to the efficiency and effectiveness of the work of the Nation's scientists and engineers. The Bureau serves also as a focal point in the Federal Government for assuring maximum application of the physical and engineering sciences to the advancement of technology in industry- and commerce. To accomplish this mission, the Bureau is organized into three institutes covering broad program areas of research and services: THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS . provides the central basis within the United States for a complete and consistent system of physical measurements, coordinates that system with the measurement systems of other nations, and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. This Institute comprises a series of divisions, each serving a classical subject matter area: —Applied Mathematics—^Electricity—Metrology—Mechanics—-Heat—Atomic Physics Physical Chemistry—Radiation Physics—Laboratory Astrophysics ^—Radio Standards Laboratory,^ which includes Radio Standards Physics and Radio Standards Engineering- Office of Standard Reference Data. THE INSTITUTE FOR MATERIALS RESEARCH . conducts materials research and provides associated materials services including mainly reference materials and data on the properties of materials. Beyond its direct interest to the Nation's scientists and engineers, this Institute yields services which are essential to the advancement of technology in industry and commerce. This Institute is organized primarily by technical fields: —Analytical Chemistry—Metallurgy'—-Reactor Radiations—^Polymers—Inorganic Mate- rials—Cryogenics ^—Materials Evaluation Laboratory—Office of Standard Reference Materials. -

Introduction to Letterpress Printing

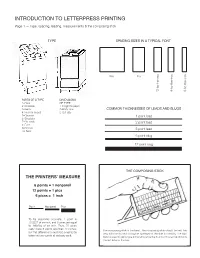

INTRODUCTION TO LETTERPRESS PRINTING Page 1 — Type, spacing, leading, measurements & the composing stick TYPE SPACING SIZES IN A TYPICAL FONT Em En 4-to-the-em 5-to-the-em *3-to-the-em PARTS OF A TYPE DIMENSIONS 1–Face OF TYPE 2–Crossbar 1–Height to paper 3–Serifs 2–Body size COMMON THICKNESSES OF LEADS AND SLUGS 4–Neck or beard 3–Set size 5–Counter 1 point lead 6–Shoulder 7–Pin mark 2 point lead 8–Feet 9–Groove 3 point lead 10–Nick 6 point slug 12 point slug THE COMPOSING STICK THE PRINTers’ Measure 6 points = 1 nonpareil 12 points = 1 pica 6 picas = 1 inch Point Nonpareil Pica To be absolutely accurate, 1 point is .013837 of an inch, and 6 picas are equal to .996264 of an inch. Thus, 72 picas really make 3 points less than 12 inches, The composing stick in the hand. The composing stick should be held this but this difference is much too small to be way, with the thumb holding the type against the side for stability. The right taken into account in all ordinary work. hand is used to place type in the stick while the thumb of the left hand holds the last letter in the line. INTRODUCTION TO LETTERPRESS PRINTING Page 2 — Parts of a Vandercook proofing press, locking up type in the bed of the press MAJOR COMPONENTS OF A CYLINDER PRESS Side guide Gripper Sheet follower or sheet finger Cylinder gear Distribution roller Cylinder bearer Form roller Rack Rail or bed bearer Register bar Bed Lock-up bar LOCK-UP FOR A CYLINDER PRESS THE BASIC CONTROLS ON A VANDERCOOK PRESS Ink power 4 2 1 4 3 4 Engage rollers 5 Print or Trip Paper or Gripper release The lock-up for a cylinder press should involve the longest furniture possible for stability. -

Dictionary of Typography and Its Accessory Arts

^-^ Ivi^ ^^^ t^^/.^ '/:^^w?y W6 Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2007 witin funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://ww.w.arcliive.org/details/dictionaryoftypoOOsout.uoft JOHAXN GUTKNBKlli; Frontispie.cf. , << li([tiajtarg 4 iUgpjrapItg ITS ACCESSORY ARTS, BY JOHN SO IT T II WA R D Corresponding Member of the FrnnkJin Societij of Chkarjo. ^jecmtb Ebitioit. LONDON: JOSEPH M. POWELL, PRINTEES' REGISTER OFFICE, ST. BRIDE STREET. 1875. : 1/^,L ; ?} ^ ^ \^ ^ LONDON PMNTBD BY JOSEPH M. POWELL, AT THE PRINl'ERS' REGISTER OFFICE, ST, BRIDE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS, E.G. PREFACE. This Dictionary of Tyj)ograpliy was originally compiled at the suggestion of the late Mr. Joseph M. Powell, and issued in monthly instalments with the Printers' Ileijister. On its comi^letion it was so well received, both by the Press and Printers generally, that a demand sprang up for copies which it was found impossible to satisfy. Mr. Powell then proposed a re-issue, and arranged with the author for the complete revision of the book. This second edition will, it is hoped, be found at least as useful to the trade as was the first. Simultaneously with its original publication in England, the Dictionary was published in the Printers' Circular of Philadelphia, United States, by the editor of which it was revised. The improvements made in this way have been adopted in preparing this edition for press. J. S. July, 1875. — list of SutliDititifs. Among the various works on the Art of Printing consulted in the compilation of this Dictionary may be named the following : Abridgments of Specifications relatinp to Printinpr. -

The Letter-Press Printer: a Complete Guide to the Art Of

University of California Berkeley f THE LETTER-PRESS PRINTER: A COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE ART OF PRINTING CONTAINING PKAOTICAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR LEARNERS AT CASE, PRESS, AND MACHINE. EMBRACING THE WHOLE PRACTICE OF BOOK-WORK.WITH DIAGRAM AND COMPLETE SCHEMES OF IMPOSITIONS; JOB WORK, WITH EXAMPLES; NEWS-WORK, COLOUR WORK, TO MAKE COLOURED INKS. TO WORK PRESS AND MACHINE, TO MAKE ROLLERS, INSTRUCTIONS IN STEREOTYPING, AND OTHER VALUABLE INFORMATION. BY JOSEPH GOULD, PRINTER. LONDON : E. MARLBOROUGH & Co., FARRINGTON & Co., 51, OLD BAILEY, E.G. 31, FETTER LANE, F&EET STREET MIDDLESBROUGH : J. GOULD, PRINTER, SOUTH STREET. (gnteb at SiH&mwre' fall STEREOTYPED BY J. QCOLO PREFACE. " THE First. Second and Third Editions of The Letter-Press " Printer having being disposed of, and a new edition inquired for, I have much pleasure in introducing to the trade a Fourth Edition. Of the First, Second and Third Editions over 9,000 copies were printed and sold, a quantity that has far exceeded my most sanguine expectations. This great success I attribute to the flattering notices of the trade journals, and to their warm recommendations of the work. I have done my utmost to improve the present edition in all the departments on which it proposes to afford instruction, and I hope my endeavours have been sufficiently successful to merit the continued approval of the trade. The Colour Printing section has been carefully read, cor- rected, and added to by a gentleman of great experience, who is at present managing one of the principal colour printing establishments in London. He pointed out some errors in that section of my First Edition, and kindly volunteered his gratuitor.s " " services to make Colour Printing more useful, reliable, and valuable in this edition. -

May 2007 Galley

INSIDE: Teaching letterpress discus- sion continues with two articles starting on... / p6 Is eBay good or bad for letterpress / p8 A monthly online publication devoted The history of to letterpress printingGalley (published Kelsey & Co. / p11 the first day of each month). GAB No. 5 / MAY 2007 OLD FLAMES MIS-MATCHED: True ofstories extinguishedTHE WHY AND HOW love OF PRINTING THE MATCHBOOKS seemed the obvious theme for a book of matches. I By Catherine Alice Michaelis was mostly concerned the whole thing was trite. t any one time there are probably about Matchbook. The name was a challenge to me. a dozen ideas careening around in my de- I had been thinking about pocketbooks, and oth- Asign mind. Structures, images, themes, and er words that suggested crossover possibilities. I influences all bouncing around until the had recently been involved in a printer’s exquisite right balls fall into the right slot in the right order. corpse project and I was still enchanted with the I am more of a writer than image-maker, so book possibilities of mix and match pages, and I had shapes and designs that get me around the image also long been contemplating Keith Smith’s ideas making process move faster through my design of an ephemeral book. process. Once the idea began evolving, old flames I spent a year thinking about printing on matches. © 2007 MIKE O’CONNOR GALLEY GAB PAGE TWO (See why faster is good?) It seemed really hard–the paper would be. I printed low on the matchsticks, matches splay at the top, could I compensate for trying to avoid as much of the chemicals as I could, that? I liked my idea a lot though, so one day on concerned they would degrade the ink. -

Historic Furnishings Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Media Services Harpers Ferry Center Historic Furnishings Report Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park Dayton, Ohio Print Shop, Hoover Block APPROVED: Lawrence Blake Superintendent, Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park February 18, 2006 Historic Furnishings Report Print Shop Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park Dayton, Ohio by Mary Grassick Staff Curator Media Services Harpers Ferry Center National Park Service, 2007 Cover: Exterior of the Hoover Block, c. 1893, Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORIC FURNISHINGS REPORT Contents Administrative Information 1 Management Background 3 Interpretive Objectives 4 Operating Plan 4 Prior Planning Documents 5 Historical Information 7 A Note on Sources 9 History of the Structure 10 Evidence Locating Print Shop on Second Floor of Hoover Block 12 Evidence of Room Finishes 13 Room 223: Composing Room 13 Room 221: Job Press Room 14 Room 222: Cylinder Press Room 15 Room 220: Hallway 15 Analysis of Historical Use and Occupancy 17 Evidence of Room Use and Furnishings 26 Printing Presses 26 Original Wright Objects 29 Imposing Table 29 Type Stands and Type Cases 29 Other Wright Materials 30 Other Printing Materials 31 Furnishings Plan 33 Print Shop Suite Floor Plan 35 List of Recommended Furnishings 36 Room 223: Composing Room 36 Room 222: Cylinder Press Room 40 Room 221: Job Press Room 42 Illustrations 45 Bibliography 103 PRINT SHOP, HOOVER BLOCK CONTENTS NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORIC FURNISHINGS REPORT Administrative Information 1 PRINT SHOP, HOOVER BLOCK ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION 2 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORIC FURNISHINGS REPORT Administrative Information Management Background to transfer the repair portion of their business 3 The Hoover Block in Dayton, Ohio, was to the print shop in the Hoover Block.2 In constructed by Zachary T. -

Two Rare Table-Top Presses at the Oxford University Museum Of

Two rare table-top presses Paul W. Nash at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History From the middle of the nineteenth century it was the regular (albeit not constant) practice of the Department of Entomology at the University of Oxford to identify specimens with printed labels, made in the Department, using a succession of small table- top presses. the first press: a ‘cowper’ The ‰rst press to be acquired was one of Edward Cowper’s ‘Parlour Presses’, manufactured and sold by Charles Holtzapƒel, as des- cribed on pages 5–48 above (see Fig. 1, 2, 5–7). At least 1,076 such presses were manufactured and sold, but very few survive. In 1971, when a facsimile of the accompanying manual, Printing apparatus for the use of amateurs, was published,1 only one had been traced (press 5 below), but now six are recorded, as follows: 1) Serial number 59. Private collection. Current whereabouts unknown. The standard model. This press had been identi‰ed by the mid-1980s when a number of replicas of press 5 (no. 940) were manufactured. The prospectus for the replicas notes the existence 1. Charles Holtzapƒel’s printing of press 59 (then in a collection in Bath, England) and describes 2 apparatus for the use of amateurs … it as ‘an earlier and frailer version’ than press 940, datable to 1840. edited by James Mosley & David However, since the press numbered 58 was sold in the spring of Chambers. London: Private Lib- 1839,3 number 59 was almost certainly manufactured and sold raries Association, 1971. 2.