As an Explanation of State Education Funding to Local School Districts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement 1

*^b THE BOOK OF THE STATES .\ • I January, 1949 "'Sto >c THE COUNCIL OF STATE'GOVERNMENTS CHICAGO • ••• • • ••'. •" • • • • • 1 ••• • • I* »• - • • . * • ^ • • • • • • 1 ( • 1* #* t 4 •• -• ', 1 • .1 :.• . -.' . • - •>»»'• • H- • f' ' • • • • J -•» J COPYRIGHT, 1949, BY THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS jk •J . • ) • • • PBir/Tfili i;? THE'UNIfTED STATES OF AMERICA S\ A ' •• • FOREWORD 'he Book of the States, of which this volume is a supplement, is designed rto provide an authoritative source of information on-^state activities, administrations, legislatures, services, problems, and progressi It also reports on work done by the Council of State Governments, the cpm- missions on interstate cooperation, and other agencies concepned with intergovernmental problems. The present suppkinent to the 1948-1949 edition brings up to date, on the basis of information receivjed.from the states by the end of Novem ber, 1948^, the* names of the principal elective administrative officers of the states and of the members of their legislatures. Necessarily, most of the lists of legislators are unofficial, final certification hot having been possible so soon after the election of November 2. In some cases post election contests were pending;. However, every effort for accuracy has been made by state officials who provided the lists aiid by the CouncJLl_ of State Governments. » A second 1949. supplement, to be issued in July, will list appointive administrative officers in all the states, and also their elective officers and legislators, with any revisions of the. present rosters that may be required. ^ Thus the basic, biennial ^oo/t q/7^? States and its two supplements offer comprehensive information on the work of state governments, and current, convenient directories of the men and women who constitute those governments, both in their administrative organizations and in their legislatures. -

Ttac E Tribution to the Florida Iffs Boys Ranch

TNE FLORIDA SHERIFFS ASSOCIATION SOLICITS NO ADYERTISING . PUBLISHED FOR AND DEDICATED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF GOOD LAW ENFORCEMENT IN FLORIDA Yol. 2, No. 9 TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA NOVEMBER, 1958 Record Cash Ranch ttift II et stem CLEARWATER —Ed C. Wright, well-known Pinellas County landowner, presented his personal check for S2,500 to Sherifl' Don Genung as a con- Sher- aw ttac e tribution to the Florida iffs Boys Ranch. PANAMA CITY—The Florida Sheriffs Budget System This is the largest cash con- tribution received to date for law which has won nation-wi de acclaim as a major advance the Ranch. Single donations of property and equipment valued in law enforcement has been attacked in circuit court here. at higher sums have been re- The Calhoun County Comm ission has filed a suit claiming ceived, however. Wright, who rarely allows his the law is unconstitutional an d asked the court to issue a name to be used when making a charitable contribution, de- temporary injunction which would prevent Sheriff W. C. clared he didn't mind publicity Reeder from receiving fund s to operate his department in this case because he was "so interested in what is being done under the budget system. Ranch. " at the Boys Sheriff Reeder, backed by the I He called upon all Florida Florida Sheriffs Association, as a general law, is actually a ( citizens to "come forth" and "this won the first round when Judge special act. They told the court support positive step" Clay Lewis denied the injunc- the law is unconstitutional be- against juvenile delinquency. -

MATTHEW T. CORRIGAN Conservative Hurricane How Jeb

WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING “A timely reminder that Jeb Bush was and remains a deep-dyed conservative who was not reluctant to magnify and use all the pow- ers of his office.”—MARTIN A. DYCKMAN, author of Reubin O’D. Askew and the Golden Age of Florida Politics “A detailed look at how Jeb Bush used enhanced consti- tutional executive powers, the first unified Republican state government elected to Tallahassee, and the force of his own personality and intellect to enact significant conservative political and policy changes in Flori- da.”—AUBREY JEWETT, coauthor of Politics in Florida, Third Edition For more information, contact the UPF Publicity Desk: (352) 392-1351 x 233 | [email protected] Available for purchase from booksellers worldwide. To order direct from the publisher, call the University Press of Florida: 1 (800) 226-3822. CONSERVATIVE HURRICANE 978-0-8130-6045-3 How Jeb Bush Remade Florida Cloth $26.95 MATTHEW T. CORRIGAN 248 pp., 9 tables UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA -OCTOBER 2014 MATTHEW T. CORRIGAN is professor and chair of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at the University of North Florida. His previous books are Race, Religion, and Economic Change and American Royalty, which focuses on the Clinton and Bush families. During the aftermath of the 2000 presidential election, he was a consultant to Duval County, Florida, and assisted county leaders in reforming the county’s voting system. During presidential and gubernatorial election nights, he works as a consultant for the Associated Press an- alyzing exit polls and turnout data for the state of Florida. -

Southern Regional Education Board Southern Regional Education Board

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by eGrove (Univ. of Mississippi) University of Mississippi eGrove Mississippi Education Collection General Special Collections 1957 Southern Regional Education Board Southern Regional Education Board Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_educ Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Southern Regional Education Board, "Southern Regional Education Board" (1957). Mississippi Education Collection. 5. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_educ/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the General Special Collections at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mississippi Education Collection by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Purpose Activities rs I l.J V] THE SoUTHERN REGIONAL EDUCATION BOARD is an agency of the Southern states, operating under an interstate compact among Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. The legislature of each of these states appropriates $20,000 a year for its operation. The states formed SREB for the purpose of making better use of colleges and universities by sharing resources for professional, technical, and graduate education. By sharing such resources, the states get more for their educational dollars. They can use college programs which already exist and do not have to establish duplicate programs in each state if such duplication is not needed. Also, the states and the institutions can jointly plan and establish new educational programs according to the needs of the region. * >I< * The Board is composed of the governors of the Southern states, ex officio, and four persons ap pointed by each. -

Reforming the Presidential Nominating Process

REFORMING THE PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATING PROCESS PAUL T. DAVID* It is the function of the presidential nominating process to identify the candidates who can be made the subject of a presidential election; it is the function of the general election to make the final choice. Because of this characteristic difference in function, the nominating process differs from the general election process in respects that are fundamental to the manner in which each should be conducted. An election for President, as long as the two-party system holds together, is essenti- ally a choice between two candidates, each of whom was formally identified some time in advance, has become familiar to the voters through active campaigning, and has the support in the election of a permanently organized national political party. None of these features is true of the nominating process. It has to begin in the first place by ascertaining the alternatives among whom a choice may be made, seldom deals with a choice between two candidates and only two, frequently involves a comparison between some candidates who are well known and others who are little known and goes on inside the political party from which support will be obtained-after the choice has been made. Much of what is most important in the nominating process occurs before there is any short list of definite candidates on whom to concentrate attention. These aspects of the process will be neglected here, moving on immediately to special char- acteristics of the nominating choice that become apparent after the field of candidates for a party nomination has become relatively clear.' SOME CHARACTErISTICs OF PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATING CHOICE I. -

Guide to the Leroy Collins Papers, 1945-1993

Guide to the Leroy Collins papers, 1945-1993 Descriptive Summary Title : Leroy Collins papers Creator: Collins, LeRoy (1909-1991) Dates : 1945-1993 ID Number : C31 Size: 471 boxes Language(s): English Repository: Special Collections University of South Florida Libraries 4202 East Fowler Ave., LIB122 Tampa, Florida 33620 Phone: 813-974-2731 - Fax: 813-396-9006 Contact Special Collections Administrative Summary Provenance: Collins, LeRoy, 1909-1991 Acquisition Information: Donation Accruals: Additional correspondence (1961-1968), film strips, tapes, and campaign materials for Collins' senatorial campaign in 1969 donated by Leroy Collins in December 1969. Access Conditions: None. The contents of this collection may be subject to copyright. Visit the United States Copyright Office's website at http://www.copyright.gov/ for more information. Processing History: Ready Preferred Citation: LeRoy Collins papers, Special Collections Department, Tampa Library, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida Related Material: Thomas LeRoy Collins Papers, Special Collections, Robert Manning Strozier Library, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida. Biographical Note LeRoy Collins was born in Tallahassee on March 10, 1909. He graduated from Leon High School in Tallahassee and received a degree in law from Cumberland University in Birmingham, Alabama. He returned to Tallahassee and married Mary Call Darby, the great-granddaughter of Richard Call who had twice served as Territorial Governor of Florida. Soon after his marriage to Mary Call, Collins was elected as the representative of Leon County to the Florida House of Representatives in 1934. He served in this position until 1940 when he filled the term of the late William Hodges in the Florida Senate. Collins purchased the Call family home "The Grove" in 1941 and shortly thereafter resigned his position from the Florida Senate to join the Navy in 1942. -

Fp37sum Leroy Collins This Is an Interview with Leroy Collins, Former Governor of Florida. the Interview Was Conducted in Tallah

FP37sum LeRoy Collins This is an interview with LeRoy Collins, former governor of Florida. The interview was conducted in Tallahassee, Florida, by Jack Bass and Walter De Vries on May 19, 1974. The interview is from the Southern Oral History Program in the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina Library, Chapel Hill. pp. 1-3: Collins opens the interview by discussing the senatorial race in 1968 in which he ran against Ed Gurney. He says the choice was simple: vote for a liberal--himself--or vote for a conservative--Ed Gurney. He adds that during the political campaign the liberal-conservative difference was based "almost wholly" on race. And it was the race issue that defeated him, he says. In the previous election, Collins recalls that the subject of race was not mentioned in the gubernatorial race, and blacks were not demanding political stances on this issue. Collins then describes George Wallace's popularity in Florida in 1968. He focuses on Wallace's well- financed and coordinated campaign, and the fact that a vote for Wallace was a vote against LeRoy Collins who stood as a liberal on the race issue. pp. 4-8: Collins refers to a speech he gave the previous evening to an audience filled with blacks and whites. The speech reviewed race relations since Brown versus The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954), and he paid tribute to blacks' progress. He also said in this speech that the gates opened to desegregation, civil rights, and opportunities as a result of people dying together, going to jail together, marching to Washington, and other such pressures to change. -

Guaranteeing Safe Passage

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. .... 7'i.: : 7-/7"?:7 ...... Guaranteeing • =:~;~'5#,:.< !:,., i:~-'~&~ ~ - . Safe Passage: The National Forum on Youth Violence made possible by 0 Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention California Wellness Foundation ? Criminal Justice Policy Foundation Cowles Charitable Trust [:. • 71• 4 %[7 " '""',-q" ~''<" ;" ..... [. • Annie E. Casey-F~r~datiOn : ii: ..... • ....: ,2. National Conference o~:S~;-~g~S{atures .[ .... '...... "~ :: '.-.;'".;"" ..... Police Executive l~esearch Forum :0 i i . Dil ¸ :. .2, ~:,~.~5 ~ ~ ~ : ~ .~,~-~.~ 7C ':~ ~'" ""' ~~;~ .... .,. ~ ~ ....... :.7..2!"~: , )~'i GuaranteeingSafePassage MateriaJs foi this Forum were prepared under Grant No. 95-JN-FX-0012 from the Office of Juvefiile Justice and Delinquency Preventio n, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U. S. Department of Justice. 0 Manual design and layout by Lisa A. Gilley, Developmental Research and Programs, Inc. Q 7:00 - 9:00 PM Dinner Dinner Speaker: Joe Marshall Agenda Views on Preventing Youth Violencefrom a Nationally Respected Youth Advocate Friday, June 2 8:00 - 9:00 AM Breakfast 9:00- 10:30 AM Panel: Balancing Enforcement and Prevention A discussion with prominent law enforcement officials who have implemented programs blending law enforcement and prevention approaches. 10:30 - 10:45 AM Break \ 10:45 - 12:15 PM Working Groups - Session III Youth Violence Prevention: What Works Youth Violence Prevention: What Doesn't Work Early Childhood Intervention Youth Speak Out Guaranteeing Safe Passage Q 12:15 - 1:45 PM Lunch Agenda Luncheon Speaker: Shay Bilchik Framing A National Agenda on Youth Violence 1:45 - 3:30 PM Panel: Next Steps - A Call to Action A discussion with Forum participants on future action steps. -

The Myth of the Cabinet System: the Need to Restructure Florida's Executive Branch

Florida State University Law Review Volume 19 Issue 4 Volume 19, Issue 4 Article 7 Spring 1992 The Myth of the Cabinet System: The Need to Restructure Florida's Executive Branch Joseph W. Landers, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Joseph W. Landers, Jr., The Myth of the Cabinet System: The Need to Restructure Florida's Executive Branch, 19 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 1089 (1992) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol19/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MYTH OF THE CABINET SYSTEM: THE NEED TO RESTRUCTURE FLORIDA'S EXECUTIVE BRANCH* JOSEPH W. LANDERS, JR.** C LAUDE Kirk became Florida's thirty-sixth Governor in 1966, the beneficiary of a bitter split between Democrats Haydon Burns and Robert King High. Kirk, a colorful and unpredictable Republican from Palm Beach, had a stormy four years, partly because of his peri- odic sniping at the six Democratic Cabinet members. The enmity was mutual; they called him "Claudius Maximus" and he called them the "six dwarfs." The first Republican governor since Reconstruction, Kirk openly ridiculed the Cabinet system. But he was neither the first nor the only governor to be critical of Florida's shared executive power. I. FLAWED SYSTEM Reubin Askew, as a member of the state Legislature -

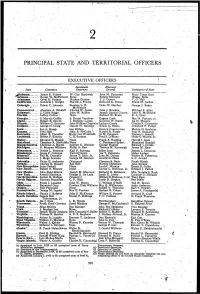

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

Complete Issue 1(4)

Speaker & Gavel Volume 1 Article 1 Issue 4 May 1964 Complete Issue 1(4) Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/speaker-gavel Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1964). Complete Issue 1(4). Speaker & Gavel, 1(4), 105-140. This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Speaker & Gavel by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. et al.: Complete Issue 1(4) k-^"-'-'. - '.3^' -*r.-i» -iix-z SPEAKER ¥0^ Jit: )l k ; % *s • is'^ 1' n ..aa'',' -.A \ i\i mM f % (U SR c-r nJSS %'£S ?S3 and asSS G A Volume 1 V Number 4 May E •»« xt* 1964 L ssu-flo^ air Published by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato,1 Speaker & Gavel, Vol. 1, Iss. 4 [], Art. 1 SPEAKER and GAVEL Official publicotion of Delta Sigma Rho-Tou Koppa Alpha National Honorary Forensic Society PUBLISHED AT LAWRENCE, KANSAS By THE ALLEN PRESS Editorial Address: Charles Goetzinger, Department of Speech and Droma Colorado University, Boulder, Colorado Second-class postage paid ot Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A. Issued in November, January, March ond May. The Journal carries no paid odvertising. TO SPONSORS AND MEMBERS Pleose send all communicotions relating The names of new members, those elected to initiation, certificotcs of membership, key between September of one year and Septem- orders, ond nomes of members to the ber of the following year, appear in Notional Secretary. -

A Guide to Civil Rights Studies

A Guide To Historical Holdings In the Eisenhower Library A Guide to Civil Rights Studies Compiled by Barbara Constable and Linda K. Smith Revised by Barbara Constable (12/03) (Library staff made additional revisions 9/04, 5/05, 4/08, 9/16, 6/17) INTRODUCTION The decade of the 1950s was an era of significant advances in the movement for racial equality for black Americans. It was the time of desegregation of the United States armed forces, desegregation of Washington, D.C., Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, and the Little Rock, Arkansas school integration crisis. This guide presents a survey of historical materials in the Eisenhower Library that relate to the civil rights movement of the late 1940s and the 1950s. Files documenting African-American experiences during World War II are also included as are collections containing information on civil rights during the 1960s and 1970s. The guide explores the extensive research potential for civil rights topics at the Eisenhower Library. It is not a complete and comprehensive account, but rather a survey of manuscript collections with high research potential, manuscript collections of lesser importance, oral history transcripts, and audiovisual materials. The guide should not be considered definitive, as the search for pertinent materials was conducted primarily at the folder title level and not for individual documents. There are, no doubt, additional references to civil rights topics in the papers of the Eisenhower Library, but locating them will require a visit to the Library and an intensive search by the researcher. A complete list of holdings is available upon request.