Ontario Wine Industry: Moving Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada

MARKET INDICATOR REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2013 Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada Source: Planet Retail, 2012. Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INSIDE THIS ISSUE Canada’s population, estimated at nearly 34.9 million in 2012, Executive Summary 2 has been gradually increasing and is expected to continue doing so in the near-term. Statistics Canada’s medium-growth estimate for Canada’s population in 2016 is nearly 36.5 million, Market Trends 3 with a medium-growth estimate for 2031 of almost 42.1 million. The number of households is also forecast to grow, while the Wine 4 unemployment rate will decrease. These factors are expected to boost the Canadian economy and benefit the C$36.8 billion alcoholic drink market. From 2011 to 2016, Canada’s economy Beer 8 is expected to continue growing with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2% and 3% (Euromonitor, 2012). Spirits 11 Canada’s provinces and territories vary significantly in geographic size and population, with Ontario being the largest 15 alcoholic beverages market in Canada. Provincial governments Distribution Channels determine the legal drinking age, which varies from 18 to 19 years of age, depending on the province or territory. Alcoholic New Product Launch 16 beverages must be distributed and sold through provincial liquor Analysis control boards, with some exceptions, such as in British Columbia (B.C.), Alberta and Quebec (AAFC, 2012). New Product Examples 17 Nationally, value sales of alcoholic drinks did well in 2011, with by Trend 4% growth, due to price increases and premium products such as wine, craft beer and certain types of spirits. -

Ontario's Local Food Report

Ontario’s Local Food Report 2015/16 Edition Table of Contents Message from the Minister 4 2015/16 in Review 5 Funding Summary 5 Achievements 5 Why Local Food Matters 6 What We Want to Achieve 7 Increasing Awareness 9 Initiatives & Achievements 9 The Results 11 Success Stories 13 Increasing Access 15 Initiatives & Achievements 15 The Results 17 Success Stories 19 Increasing Supply and Sales 21 Initiatives & Achievements 21 The Results 25 Success Stories 27 The Future of Local Food 30 Message from the Minister Ontario is an agri-food powerhouse. Our farmers harvest an impressive abundance from our fields and farms, our orchards and our vineyards. And our numerous processors — whether they be bakers, butchers, or brewers — transform that bounty across the value chain into the highest-quality products for consumers. Together, they generate more than $35 billion in GDP and provide more than 781,000 jobs. That is why supporting the agri-food industry is a crucial component of the Ontario government’s four-part plan for building our province up. Ontario’s agri-food industry is the cornerstone of our province’s success, and the government recognizes not only its tremendous contributions today, but its potential for growth and success in the future. The 2013 Local Food Act takes that support further, providing the foundation for our Local Food Strategy to help increase demand for Ontario food here at home, create new jobs and enhance the economic contributions of the agri-food industry. Ontario’s Local Food Strategy outlines three main objectives: to enhance awareness of local food, to increase access to local food and to boost the supply of food produced in Ontario. -

Regulatory and Institutional Developments in the Ontario Wine and Grape Industry

International Journal of Wine Research Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article OrigiNAL RESEARCH Regulatory and institutional developments in the Ontario wine and grape industry Richard Carew1 Abstract: The Ontario wine industry has undergone major transformative changes over the last Wojciech J Florkowski2 two decades. These have corresponded to the implementation period of the Ontario Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) Act in 1999 and the launch of the Winery Strategic Plan, “Poised for 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Pacific Agri-Food Research Greatness,” in 2002. While the Ontario wine regions have gained significant recognition in Centre, Summerland, BC, Canada; the production of premium quality wines, the industry is still dominated by a few large wine 2Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of companies that produce the bulk of blended or “International Canadian Blends” (ICB), and Georgia, Griffin, GA, USA multiple small/mid-sized firms that produce principally VQA wines. This paper analyzes how winery regulations, industry changes, institutions, and innovation have impacted the domestic production, consumption, and international trade, of premium quality wines. The results of the For personal use only. study highlight the regional economic impact of the wine industry in the Niagara region, the success of small/mid-sized boutique wineries producing premium quality wines for the domestic market, and the physical challenges required to improve domestic VQA wine retail distribution and bolster the international trade of wine exports. Domestic success has been attributed to the combination of natural endowments, entrepreneurial talent, established quality standards, and the adoption of improved viticulture practices. -

2020 Canada Province-Level Wine Landscapes

WINE INTELLIGENCE CANADA PROVINCE-LEVEL WINE LANDSCAPES 2020 FEBRUARY 2020 1 Copyright © Wine Intelligence 2020 • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means) without the permission of the copyright owners. Application for permission should be addressed to Wine Intelligence. • The source of all information in this publication is Wine Intelligence unless otherwise stated. • Wine Intelligence shall not be liable for any damages (including without limitation, damages for loss of business or loss of profits) arising in contract, tort or otherwise from this publication or any information contained in it, or from any action or decision taken as a result of reading this publication. • Please refer to the Wine Intelligence Terms and Conditions for Syndicated Research Reports for details about the licensing of this report, and the use to which it can be put by licencees. • Wine Intelligence Ltd: 109 Maltings Place, 169 Tower Bridge Road, London SE1 3LJ Tel: 020 73781277. E-mail: [email protected]. Registered in England as a limited company number: 4375306 2 CONTENTS ▪ How to read this report p. 5 ▪ Management summary p. 7 ▪ Wine market provinces: key differences p. 21 ▪ Ontario p. 32 ▪ Alberta p. 42 ▪ British Colombia p. 52 ▪ Québec p. 62 ▪ Manitoba p. 72 ▪ Nova Scotia p. 82 ▪ Appendix p. 92 ▪ Methodology p. 100 3 CONTENTS ▪ How to read this report p. 5 ▪ Management summary p. 7 ▪ Wine market provinces: key differences p. 21 ▪ Ontario p. 32 ▪ Alberta p. 42 ▪ British Colombia p. 52 ▪ Québec p. -

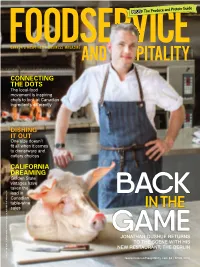

Connecting the Dots

CONNECTING THE DOTS The local-food movement is inspiring chefs to look at Canadian ingredients differently DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to dinnerware and cutlery choices CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden State vintages have taken the lead in Canadian table-wine sales JONATHAN GUSHUE RETURNS TO THE SCENE WITH HIS NEW RESTAURANT, THE BERLIN CANADIAN PUBLICATION MAIL PRODUCT SALES AGREEMENT #40063470 CANADIAN PUBLICATION foodserviceandhospitality.com $4 | APRIL 2016 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2016 CONTENTS 40 27 14 Features 11 FACE TIME Whether it’s eco-proteins 14 CONNECTING THE DOTS The 35 CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden or smart technology, the NRA Show local-food movement is inspiring State vintages have taken the lead aims to connect operators on a chefs to look at Canadian in Canadian table-wine sales host of industry issues ingredients differently By Danielle Schalk By Jackie Sloat-Spencer By Andrew Coppolino 37 DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit 22 BACK IN THE GAME After vanish - all when it comes to dinnerware and ing from the restaurant scene in cutlery choices By Denise Deveau 2012, Jonathan Gushue is back CUE] in the spotlight with his new c restaurant, The Berlin DEPARTMENTS By Andrew Coppolino 27 THE SUSTAINABILITY PARADIGM 2 FROM THE EDITOR While the day-to-day business of 5 FYI running a sustainable food operation 12 FROM THE DESK is challenging, it is becoming the new OF ROBERT CARTER normal By Cinda Chavich 40 CHEF’S CORNER: Neil McCue, Whitehall, Calgary PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY [NEIL M OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE FOODSERVICEANDHOSPITALITY.COM FOODSERVICE AND HOSPITALITY APRIL 2016 1 FROM THE EDITOR For daily news and announcements: @foodservicemag on Twitter and Foodservice and Hospitality on Facebook. -

GGO Newsletter

Newsletter - Volume 1 - January/February 2011 ...Dedicated to the Success of Ontario’s Grape Growers 2011 Grapes for Processing Pricing Agreement The Grape Growers of Ontario (GGO), Wine Council of Ontario (WCO) and Winery & Grower Alliance of Ontario (WGAO) have agreed to extend the 2010 pricing arrangement into 2011, which includes the Plateau Pricing model for four grape varieties - Chardonnay, Riesling, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. The changes for the 2011 Pricing Plan are outlined as follows: 2011 Pricing Plan The parties have agreed to a 1% increase over 2010V prices for all white varieties (Vinifera and Hybrid). The red varieties (Vinifera and Hybrid) remain stable at the current 2010V pricing. Pilot Plateau Pricing Model for 4 Varieties for 2011 It was agreed by all parties to continue the Plateau Pricing model on four varieties for 2011: Chardonnay, Ries- ling, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. It is important to note that any grapes purchased for Plateau Pricing in 2011 are not subject to tonnage restrictions and all processors participating in the program will need to work with their growers to ensure this parameter is applied. 2011 Grape Growers of Ontario Inside this issue: 2011 Pricing Agreement 1 Annual General Meeting Focus on the Grower 2 Wednesday April 6, 2011 at 7:00 pm Annual General Meeting 3 Savvy Farmer 4 Club Roma—125 Vansickle Road, St. Catharines CleanFARMS™ 5 IMPORTANT: Voter Registration from 6:00—6:45 pm In Memoriam 6 See page 3 for additional information Upcoming Events 7 Industry News/Classified 8 GGO Services Grape Pricing & Promotion Government Lobbying Nutrient Management Grape Research Government Policies & Regulations Crop Insurance Requirements Grape Inspection Farm Labour Legislation & Program Business Risk Management (CAIS & SDRM) Government & Industry Relations Chemical Registration Weather INnovations Incorporated (WIN) P.O. -

Favourite Wine Styles & Perfect Food Pairings

FAVOURITE WINE STYLES & PERFECT FOOD PAIRINGS WASHINGTON & OREGON WINES 33550 DISCOVER OUR LATEST COLLECTION, IN STORES AND ONLINE SATURDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2020 33550_Vin.Oct03_Covers.indd 3 2020-08-27 4:12 PM wines of the month welcomeoctober 3 Intriguing reds for fall contemplation pg.2 MONTGRAS INTRIGA CABERNET SAUVIGNON 2016 Maipo Valley, Chile 57901 (XD) 750 mL $22.95 MATCH TASTING NOTE: Intriga has been produced since the 2005 vintage, always with grapes MAKING from vineyards planted in the Linderos zone 70 years ago. The base of cabernet sauvignon amounts to 82% of the final blend this year, along with cabernet franc and a few drops of petit verdot. It was a cold year with heavy rains ... [that] gave rise to fresher, lighter wines, and this Intriga is a good example. The grapes that went into this blend were harvested before the Easter rains, and that made the character much pg.14 nervier than usual in a medium-bodied wine SHOP with deliciously bright acidity. Score: 94 BEST BY (Descorchados, 2020) LCBO.COM NORTHWEST Try Same-Day Pickup! Medium-bodied & Fruity See page 50 for details. plus... GODELIA MENCIA RED 2015 PRODUCT INFO & TASTING NOTES DO Bierzo, Spain pages 2949 368043 (XD) 750 mL $24.95 SHOPPING LIST TASTING NOTE: Black cherry, plum and pg.24 pages 5152 currant flavors give this red a rich core of FLAGSHIP EXCLUSIVES fruit, while leafy, licorice and mineral notes HOME FOR pages 5355 add complexity. Well-integrated tannins pg. 28 THANKSGIVING and gentle acidity focus the plush texture. LOCAL FIND VISIT THE GIN SHOP Harmonious, showing good depth. -

Winery & Grower Alliance of Ontario

Winery & Grower Alliance of Ontario 2011-2012 Annual Report Message from the Chair The 2011/12 year for the Winery In March of 2012 the WGAO and the GGO co-sponsored the & Grower Alliance of Ontario industry conference Insight 2012 in Niagara on the Lake. This (WGAO) was the first full year of conference brought together 130 representatives from across operation for the organization with the industry, government and the LCBO. This serves as just one management in place. As a new example of how the WGAO translates its Vision and Mission alliance we focused on building for the entire industry into action. strong relationships with provincial Based on feedback the WGAO created a category for Regional and federal governments as well as Association Membership. We are pleased that Essex Pelee other stakeholders in the industry. Island Coast (EPIC) Winegrowers Association (formerly The WGAO firmly believes that Southwestern Ontario Vintners Association) joined the WGAO Anthony Bristow, Chair the industry will grow and flourish this year. with wineries and grape growers Finally, we were extremely pleased to play a leadership role in working seamlessly together. In all of our Board of Directors establishing a new two year Plateau Pricing and fixed base brix discussions we evaluate policy and program advocacy positions structure and two year pricing schedule, which will provide based upon whether the entire industry will benefit, including much needed stability and predictability for both wineries and both grape growers and wineries. It is important to us that grape growers. we act based upon facts and information, and with complete transparency. -

Supporting 15 Years of Ontario Wine Industry Growth Taste the Place

VQA OntAriO Supporting 15 years of Ontario wine industry growth TASTE THE PLACE VQA is about place. Special places right here at home. Places like nowhere else in the world. Where the soil, the slope, the sunshine, the warmth, the rainfall and the craftsmanship all matter. Together, they give us better grapes. And better grapes give us better wine. 2015 17 155 97% 2015 17 155 97% 2015 17 155 97% 2000 4 44 80% 2000 4 44 80% 2000 4 44 80% Regulated 2015VQA Ontario Annual success appellations and members rate of VQA wine 97% sub-appellations 17 1approvals55 Regulated VQA Ontario Annual success Regulated VQAVQA Ontario Fast FactsAnnual success appellations and members rate of VQA wine appellations and members rate of VQA wine sub-appellations approvals sub-appellations approvals Each bottle of VQA wine sold in Ontario generates 73% ofin Ontario wine VQA $360 2015 $ in consumers know 12.29VQA QUALITYequ $ $ in 2015 $ MILLION VQA 3603602015 $2000 12.294 44 the term VQA andequ 80% o equ & ORIGIN MILLION 12.29 associate QUALITYit with ONTARIOQUALITY MILLION $ qualityin and origin. o 168 2008 & ORIGIN ECONOMY& ORIGIN ONTARIO o MILLION $ in ONTARIO 1$68 2008 in ECONOMYRegulated VQA Ontario Annual success MILLION168 2008 ECONOMYappellations and members rate of VQA wine MILLION sub-appellations approvals Wine consumers now $ in VQA 360 2015 associate$ a higher value equ MILLION with VQA wines12.29 that offer QUALITY a distinct sense of place. & ORIGIN ONTARIOo in $168 2008 ECONOMY MILLION $ $15 $20 26 VQA VQA VQA APPELLATION SUB- ONTARIO eg. NIAGARA APPELLATION PENINSULA eg. -

Culinary Chronicles

Culinary Chronicles The Newsletter of the Culinary Historians of Canada AUTUMN 2010 NUMBER 66 “Indian method of fishing on Skeena River,” British Columbia Dominion Illustrated Monthly, August 4, 1888 (Image courtesy of Mary Williamson) ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Contents President’s Message: We are now the In a Circular Line It All Comes Back Culinary Historians of Canada! 2 Vivien Reiss 16, 18 Members’ News 2 An Ode to Chili Sauce Indigenous Foodways of Northern Ontario Margaret Lyons 17, 18, 21 Connie H. Nelson and Mirella Stroink 3–5 Book Reviews: Speaking of Food, No. 2: More than Pachamama Caroline Paulhus 19 Pemmican: First Nations’ Food Words Foodies: Democracy and Distinction Gary Draper 6–8 in the Gourmet Foodscape Tea with an Esquimaux Lady 8 Anita Stewart 20 First Nation’s Ways of Cooking Fish 9 Just Add Shoyu Margaret Lyons 21 “It supplied such excellent nourishment” Watching What We Eat Dean Tudor 22 – The Perception, Adoption and Adaptation Punched Drunk Dean Tudor 22–23 of 17th-Century Wendat Foodways by the CHC Upcoming Events 23 French Also of Interest to Members 23 Amy Scott 10–15 About CHC 24 Lapin Braisé et Têtes de Violon 15 2 Culinary Chronicles _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ President’s Message: We are now the Culinary Historians of Canada! Thank you to everyone who voted on our recent resolution to change the Culinary Historians of Ontario to the Culinary Historians of Canada. This important decision deserved a vote from the whole membership, and it was well worth the effort of distributing and counting ballots. Just over 60% of members cast their ballots, favouring by a wide margin of 4:1 to change the organization's name. -

Canada's Wine Associations

Take a Tour: Canada’s Wine Associations NATIONAL Canadian Vintners Association – www.canadianvintners.com The Canadian Wine Institute was created in 1967 and renamed in 2000 to the Canadian Vintners Association (CVA) to better reflect the growth of this dynamic industry. Today, CVA represents over 90% of all wine produced in Canada, including 100% Canadian, Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) wines and International-Canadian Blended (ICB) wine products. Its members are also engaged in the entire wine value chain: from grape growing, farm management, grape harvesting, research, wine production, bottling, retail sales and tourism. CVA holds the trademarks to Vintners Quality Alliance, Icewine and Wines of Canada. Stated Mission: To provide focused national leadership and strategic coherence to enable domestic and international success for the Canadian wine industry. PROVINCIAL BRITISH COLUMBIA British Columbia Wine Institute – www.winebc.org The British Columbia Wine Institute (BCWI) was created by the Provincial Government to give the wine industry an industry elected voice representing the needs of the BC wine industry, through the British Columbia Wine Act in 1990. In 2006, BCWI members voted to become a voluntary trade association with member fees to be based on BC wine sales. Today, BCWI plays a key role in the growth of BC’s wine industry and its members represent 95% of total grape wine sales and 94% of total BC VQA wine sales in British Columbia. Stated Mission: To champion the interests of the British Columbia wine industry and BC VQA wine through marketing, communications and advocacy of its products and experiences to all stakeholders. Additional British Columbia wine-related organizations: British Columbia Wine Authority – www.bcvqa.ca The British Columbia Wine Authority (BCWA) is an independent regulatory authority to which the Province of British Columbia has delegated responsibility for enforcing the Province’s Wines of Marked Quality Regulation, including BC VQA Appellation of origin system and certification of 100% BC wine origins. -

List of Suppliers As of October 17, 2018

List of Suppliers as of October 17, 2018 1006547746 1 800 WINE SHOPCOM INC 525 AIRPARK RD NAPA CA 945587514 7072530200 1018334858 1 SPIRIT 3830 VALLEY CENTRE DR # 705-903 SAN DIEGO CA 921303320 8586779373 1017328129 10 BARREL BREWING CO 62970 18TH ST BEND OR 977019847 5415851007 1018691812 10 BARREL BREWING IDAHO LLC 826 W BANNOCK ST BOISE ID 837025857 5415851007 1001989813 14 HANDS WINERY 660 FRONTIER RD PROSSER WA 993505507 4254881133 1035490358 1849 WINE COMPANY 4441 S DOWNEY RD VERNON CA 900582518 8185813663 1006562982 21ST CENTURY SPIRITS 6560 E WASHINGTON BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 900401822 1016418833 220 IMPORTS LLC 3792 E COVEY LN PHOENIX AZ 850505002 6024020537 1008951900 3 BADGE MIXOLOGY 880 HANNA DR AMERICAN CANYON CA 945039605 7079968463 1016333536 3 CROWNS DISTRIBUTORS 534 MONTGOMERY AVE STE 202 OXNARD CA 930360815 8057972127 1039154000 503 DISTILLING LLC 275 BEAVERCREEK RD STE 149 OREGON CITY OR 970454171 5038169088 1039152554 5STAR ESPIRIT LLC 1884 THE ALAMEDA SAN JOSE CA 951261733 2025587077 1038066492 8 BIT BREWING COMPANY 26755 JEFFERSON AVE STE F MURRIETA CA 925626941 9516772322 1014665400 8 VINI INC 1250 BUSINESS CENTER DR SAN LEANDRO CA 945772241 5106758888 1014476771 88 SPIRITS CORP 1701 S GROVE AVE STE D ONTARIO CA 917614500 9097861071 1015273823 90+ CELLARS 499 MOORE LANE HEALDSBURG CA 95448 7075288500 1006630333 A HARDY USA LTD 1400 E TOUHY AVE STE 120 DES PLAINES IL 600183338 7079967135 1006578404 A RAFANELLI WINERY 4685 W DRY CREEK RD HEALDSBURG CA 954488124 7074331385 1006641998 A TO Z/REX HILL/FRANCIS TANNAHILL/