The Defence of Contextual Truth and Hore Lacy: Struggling but Still Standing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Running Drama in Theatre of Public Shame

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Long-running drama in theatre of public shame MP Daryl Maguire and NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian in Wagga in 2017. Tom Dusevic OCTOBER 16, 2020 The British have epic soap Coronation Street. Latin Americans crave their telenovelas. The people of NSW must settle for the Independent Commission Against Corruption and its popular offshoot, Keeping Up with the Spivs. The current season is one of the most absorbing: bush huckster Daz Kickback ensnares Gladys Prim in his scams. At week’s end, our heroine is tied to railroad tracks as a steaming locomotive rounds the bend. Stay tuned. In recent years the public has heard allegations of Aldi bags stuffed with cash and delivered to NSW Labor’s Sussex Street HQ by Chinese property developer Huang Xiangmo. In 2013 corruption findings were made against former Labor ministers Eddie Obeid and Ian Macdonald. The following year, Liberal premier Barry O’Farrell resigned after ICAC obtained a handwritten note that contradicted his claims he did not receive a $3000 bottle of Grange from the head of Australian Water Holdings, a company linked to the Obeids. The same year ICAC’s Operation Spicer investigated allegations NSW Liberals used associated entities to disguise donations from donors banned in the state, such as property developers. Ten MPs either went to the crossbench or quit politics. ICAC later found nine Liberal MPs acted with the intention of evading electoral funding laws, with larceny charges recommended against one. Years earlier there was the sex-for- development scandal, set around the “Table of Knowledge” at a kebab shop where developers met officials from Wollongong council. -

1. Gina Rinehart 2. Anthony Pratt & Family • 3. Harry Triguboff

1. Gina Rinehart $14.02billion from Resources Chairman – Hancock Prospecting Residence: Perth Wealth last year: $20.01b Rank last year: 1 A plunging iron ore price has made a big dent in Gina Rinehart’s wealth. But so vast are her mining assets that Rinehart, chairman of Hancock Prospecting, maintains her position as Australia’s richest person in 2015. Work is continuing on her $10billion Roy Hill project in Western Australia, although it has been hit by doubts over its short-term viability given falling commodity prices and safety issues. Rinehart is pressing ahead and expects the first shipment late in 2015. Most of her wealth comes from huge royalty cheques from Rio Tinto, which mines vast swaths of tenements pegged by Rinehart’s late father, Lang Hancock, in the 1950s and 1960s. Rinehart's wealth has been subject to a long running family dispute with a court ruling in May that eldest daughter Bianca should become head of the $5b family trust. 2. Anthony Pratt & Family $10.76billion from manufacturing and investment Executive Chairman – Visy Residence: Melbourne Wealth last year: $7.6billion Rank last year: 2 Anthony Pratt’s bet on a recovering United States economy is paying off. The value of his US-based Pratt Industries has surged this year thanks to an improving manufacturing sector and a lower Australian dollar. Pratt is also executive chairman of box maker and recycling business Visy, based in Melbourne. Visy is Australia’s largest private company by revenue and the biggest Australian-owned employer in the US. Pratt inherited the Visy leadership from his late father Richard in 2009, though the firm’s ownership is shared with sisters Heloise Waislitz and Fiona Geminder. -

The Sydney Morning Herald's Linton Besser and the Incomparable

Exposed: Obeids' secret harbour deal Date May 19, 2012 Linton Besser, Kate McClymont The former ALP powerbroker Eddie Obeid hid his interests in a lucrative cafe strip. Moses Obeid. Photo: Kate Geraghty FORMER minister Eddie Obeid's family has controlled some of Circular Quay's most prominent publicly-owned properties by hiding its interests behind a front company. A Herald investigation has confirmed that Mr Obeid and his family secured the three prime cafes in 2003 and that for his last nine years in the upper house he failed to inform Parliament about his family's interest in these lucrative government leases. Quay Eatery, Wharf 5. Photo: Mick Tsikas For the first time, senior officials and former cabinet ministers Carl Scully and Eric Roozendaal have confirmed Mr Obeid's intervention in the lease negotiations for the quay properties, including seeking favourable conditions for the cafes, which the Herald can now reveal he then secretly acquired. Crucially, when the former NSW treasurer Michael Costa had charge of the waterfront, he put a stop to a public tender scheduled for 2005 that might have threatened the Obeids' control over two of the properties. Mr Obeid was the most powerful player inside the NSW Labor Party for the past two decades, and was described in 2009 by the deposed premier Nathan Rees as the party's puppet-master. Eddie Obeid. Photo: Jon Reid The Arc Cafe, Quay Eatery and Sorrentino, which are located in blue-ribbon positions on or next to the bustling ferry wharves at the quay, are all run by a $1 company called Circular Quay Restaurants Pty Ltd. -

Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45Th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief Lists

Barton Deakin Brief: Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief lists individuals and institutions on Twitter relevant to policy and political developments in the federal government domain. These institutions and individuals either break policy-political news or contribute in some form to “the conversation” at national level. Being on this list does not, of course, imply endorsement from Barton Deakin. This Brief is organised by categories that correspond generally to portfolio areas, followed by categories such as media, industry groups and political/policy commentators. This is a “living” document, and will be amended online to ensure ongoing relevance. We recognise that we will have missed relevant entities, so suggestions for inclusions are welcome, and will be assessed for suitability. How to use: If you are a Twitter user, you can either click on the link to take you to the author’s Twitter page (where you can choose to Follow), or if you would like to follow multiple people in a category you can click on the category “List”, and then click “Subscribe” to import that list as a whole. If you are not a Twitter user, you can still observe an author’s Tweets by simply clicking the link on this page. To jump a particular List, click the link in the Table of Contents. Barton Deakin Pty. Ltd. Suite 17, Level 2, 16 National Cct, Barton, ACT, 2600. T: +61 2 6108 4535 www.bartondeakin.com ACN 140 067 287. An STW Group Company. SYDNEY/MELBOURNE/CANBERRA/BRISBANE/PERTH/WELLINGTON/HOBART/DARWIN -

Legislative Council

22912 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday 19 May 2010 __________ The President (The Hon. Amanda Ruth Fazio) took the chair at 2.00 p.m. The President read the Prayers. APPROPRIATION (BUDGET VARIATIONS) BILL 2010 WEAPONS AND FIREARMS LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2010 Bills received from the Legislative Assembly. Leave granted for procedural matters to be dealt with on one motion without formality. Motion by the Hon. Tony Kelly agreed to: That the bills be read a first time and printed, standing orders be suspended on contingent notice for remaining stages and the second readings of the bills be set down as orders of the day for a later hour of the sitting. Bills read a first time and ordered to be printed. Second readings set down as orders of the day for a later hour. PRIVILEGES COMMITTEE Report: Citizen’s Right of Reply (Mrs J Passas) Motion by the Hon. Kayee Griffin agreed to: That the House adopt the report. Pursuant to standing orders the response of Mrs J. Passas was incorporated. ______ Reply to comments by the Hon Amanda Fazio MLC in the Legislative Council on 18 June 2009 I would like to reply to comments made by the Hon Amanda Fazio MLC on 18 June 2009 in the Legislative Council about myself. Ms Fazio makes two accusations, which adversely affect my reputation: That I am "an absolute lunatic"; and That apart from "jumping on the bandwagon of a genuine community campaign for easy access" at Summer Hill railway station, I did not have anything to do with securing the easy access upgrade at Summer Hill. -

Legislative Council

5243 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday 25 September 2002 ______ The President (The Hon. Dr Meredith Burgmann) took the chair at 11.00 a.m. The President offered the Prayers. DISTINGUISHED VISITORS The PRESIDENT: I welcome into the President's gallery the Ambassador for The Netherlands, Dr Hans Sondaal, and Mrs Els Sondaal and the Consul General of The Netherlands, Madelien de Planque. FARM DEBT MEDIATION AMENDMENT BILL CRIMES (ADMINISTRATION OF SENTENCES) FURTHER AMENDMENT BILL AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY SERVICES AMENDMENT (INTERSTATE ARRANGEMENTS) BILL Bills received and read a first time. Motion by the Hon. Michael Egan agreed to: That standing orders be suspended to allow the passing of the bills through all is remaining stages during the present or any one sitting of the House. LAND AND ENVIRONMENT COURT AMENDMENT BILL Message received from the Legislative Assembly agreeing to the Legislative Council's amendments. AUDIT OFFICE Report The President tabled, in accordance with the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, the performance audit report entitled "e-government: Electronic Procurement of Hospital Supplies" dated September 2002. Ordered to be printed. TABLING OF PAPERS The Hon. Carmel Tebbutt tabled the following papers: (1) Bank Mergers (Application of Laws) Act 1996—Treasurer's Report on the Statutory Five Year Review, dated September 2002. (2) Bank Mergers Act 1996—Treasurer's Report on the Statutory Report on the Statutory Five Year Review, dated September 2002. Ordered to be printed. BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE Withdrawal of Business Business of the House Notice of Motion No. 1, withdrawn by the Hon. Richard Jones. 5244 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL 25 September 2002 BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE Suspension of Standing and Sessional Orders Motion by the Hon. -

Scheme Booklet Registered with Asic

QMS Media Limited 214 Park Street South Melbourne, VIC 3205 T +61 3 9268 7000 www.qmsmedia.com ASX Release 13 December 2019 SCHEME BOOKLET REGISTERED WITH ASIC QMS Media Limited (ASX:QMS) refers to its announcement dated 12 December 2019 in which it advised that the Federal Court had made orders approving: • the dispatch of a Scheme Booklet to QMS shareholders in relation to the previously announced Scheme of Arrangement with Shelley BidCo Pty Ltd, an entity controlled by Quadrant Private Entity and its institutional partners (Scheme); and • the convening of meetings of QMS shareholders to consider and vote on the Scheme. The Scheme Booklet has been registered today by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. A copy of the Scheme Booklet, including the Independent Expert's Report and the notices of the Scheme Meetings, is attached to this announcement and will be dispatched to QMS' shareholders before Thursday 19 December 2019. Key events and indicative dates The key events (and expected timing of these) in relation to the approval and implementation of the Scheme are as follows: Event Date Scheme Booklet dispatched to QMS shareholders Before Thursday 19 December 2019 General Scheme Meeting 10.00am on Thursday 6 February 2020 Rollover Shareholders Scheme Meeting Thursday 6 February (immediately following the General Scheme Meeting) Second Court Hearing Monday 10 February 2020 Effective Date Tuesday 11 February 2020 Scheme Record Date 5.00pm on Friday 14 February 2020 Implementation Date Friday 21 February 2020 Note: All dates following the date of the General Scheme Meeting and the Rollover Shareholders Scheme Meeting are indicative only and, among other things, are subject to all necessary approvals from the Court and any other regulatory authority and satisfaction or (if permitted) waiver of all conditions precedent in the Scheme Implementation Deed. -

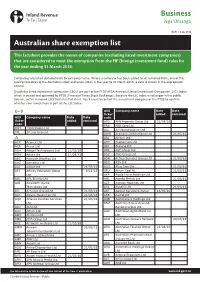

Australian Share Exemption List

Business Ngā Ūmanga IR871 | June 2016 Australian share exemption list This factsheet provides the names of companies (excluding listed investment companies) that are considered to meet the exemption from the FIF (foreign investment fund) rules for the year ending 31 March 2016. Companies are listed alphabetically by company name. Where a company has been added to, or removed from, one of the qualifying indices of the Australian stock exchange (ASX) in the year to 31 March 2016, a date is shown in the appropriate column. Qualifying listed investment companies (LICs) are part of the FTSE AFSA Australia Listed Investment Companies (LIC) Index which is owned and operated by FTSE (Financial Times Stock Exchange). Because the LIC index is no longer in the public domain, we’ve removed LICs from this factsheet. You’ll need to contact the investment company or the FTSE to confirm whether your investment is part of the LIC Index. 0–9 ASX Company name Date Date ticker added removed ASX Company name Date Date code ticker added removed APD APN Property Group Ltd 21/03/16 code ARB ARB Corp Ltd ONT 1300 Smiles Ltd ALL Aristocrat Leisure Ltd 3PL 3P Learning Ltd AWN Arowana International Ltd 21/03/16 A ARI Arrium Ltd ACX Aconex Ltd AHY Asaleo Care Ltd ACR Acrux Ltd AIO Asciano Ltd ADA Adacel Technologies Ltd 21/03/16 AFA ASF Group Ltd ADH Adairs Ltd 21/09/15 ASZ ASG Group Ltd ABC Adelaide Brighton Ltd ASH Ashley Services Group Ltd 21/03/16 AHZ Admedus Ltd ASX ASX Ltd ADJ Adslot Ltd 21/03/16 AGO Atlas Iron Ltd 21/03/16 AFJ Affinity Education Group 2/12/15 -

Federal Court of Australia

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA Fairfax Media PublicatÍons Pty Ltd v Reed International Books Australia Pty Lrd [2010] FCA 984 Citation: Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Reed International Books Australia Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 984 Parties: FAIRF'AX MEDIA PUBLICATIONS PTY LTD (ACN 003 357 720) v REED INTERNATIONAL BOOKS AUSTRALIA pTy LTD (ACN 001 002 357) T/A LEXIS.NEXIS File number: NSD 1306 of 2007 Judge: BENNETT J Date ofjudgment: 7 September 2010 Catchwords: COPYRIGHT - respondent reproduces headlines and creates abstracts of arlicles in the applicant's newspaper - whether reproduction of headlines constitutes copyright infringernent - whether copyright subsists in individual newspaper headlines, in an article with its headline, in the compilation of all the articles and headlines in a newspaper edition and in the compilation of the edition as a whole - literary work - copyright protection for titles - use of headline as citation to article - policy considerations - originality - authorship - whether presumption of originality for anonymous works available - whether work ofjoint authorship - whether the headlines constitute a substantial part of each compilation - whether the work of writing headlines is part of the work of compilation - whether fair dealing for the pu{pose of or associated with reporting news ESTOPPEL - whether applicant estopped from asserting copyright infringement by respondent - applicant has known for many years that heacllines of the applicant,s newspaper are reproduced in the abstracting service - applicant had -

Trust and Political Behaviour Jonathan O’Dea1 Member for Davidson in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Trust and Political Behaviour Jonathan O’Dea1 Member for Davidson in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly INTRODUCTION: THE DECLINE IN TRUST Trust is the most important asset in politics. Trust can generate community and business confidence, leading to economic growth and improved political success for an incumbent government. The more a government is trusted, the more people and business will generally spend and invest, boosting the economy. People are also more likely to pay their taxes and comply with regulations if they trust government. Trust promotes a social environment of optimism, cohesion and national prosperity. When trust is lost, it is difficult to win back. Where it is eroded, a general malaise can develop that is destructive to the essential fabric of society and operation of democracy. Unfortunately, in Australia and internationally, there has been a growing erosion of trust in politicians and in politics. People are losing trust in institutions including governments, charities, churches, media outlets and big businesses. In a recent Essential Poll, 45 percent of those surveyed said they had no trust in political parties, 29 percent had no trust in state parliaments and 32 percent had no trust in federal Parliament.2 Since 1969, when Australians were first surveyed about their trust in politicians, the proportion of voters saying government in Australia could be trusted has fallen from 51 percent to just 26 percent in 2016, while the number of voters who believe ‘people in government look after themselves’ has increased from 49 percent to 75 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Australasian Study of Parliament Group Conference held in Brisbane on 18-20 July 2018. -

Framing the NBN: an Analysis of Newspaper Representations

Framing the NBN: An Analysis of Newspaper Representations Rowan Wilken, Swinburne University of Technology Jenny Kennedy, University of Melbourne Michael Arnold, University of Melbourne Martin Gibbs, University of Melbourne Bjorn Nansen, University of Melbourne Abstract The National Broadband Network (NBN), Australia’s largest public infrastructure project, was initiated to deliver universal access to high-speed broadband. Since its announcement, the NBN has attracted a great deal of media coverage, coupled with at times divisive political debate around delivery models, costs and technologies. In this article we report on the results of a pilot study of print media coverage of the NBN. Quantitative and qualitative content analysis techniques were used to examine how the NBN was represented in The Age and The Australian newspapers during the period from 1 July 2008 to 1 July 2013. Our findings show that coverage was overwhelmingly negative and largely focused on the following: potential impacts on Telstra; lack of a business plan, and of cost-benefit analysis; problems with the rollout; cost to the federal budget; and implications for business stakeholders. In addition, there were comparatively few articles on potential societal benefits, applications and uses, and, socio-economic implications. Keywords: National Broadband Network, media representations, The Age, The Australian, newspaper coverage, content analysis Introduction The success of the National Broadband Network (NBN) in fulfilling its ambition to provide high-speed broadband to every business and household in the country, grow the digital economy, and support digital inclusion will be shaped by how it is understood, adopted, and appropriated by end-users. Since the project was announced on 7 April 2009 by the then- Labor Federal Government, the NBN has attracted a great deal of media coverage, coupled with, at times, divisive political debate around the model, costs and technology best fit for purpose. -

For Years Eddie Obeid Fended Off All Allegations. Now the Truth Can't Be

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For years Eddie Obeid fended off all allegations. Now the truth can’t be denied I was among those who first reported on Eddie Obeid’s dealings in the NSW Upper Hunter. Monday’s supreme court verdict is vindication for many who investigated him The NSW supreme court has found Eddie Obeid (pictured), his son Moses and former mineral resources minister Ian Macdonald guilty of conspiracy over the granting of the controversial coal exploration licence in the NSW Bylong Valley. Anne Davies Tue 20 Jul 2021 “If it is corruption, then it is corruption on a scale probably unexceeded since the days of the Rum Corps,” counsel assisting the NSW Independent Commission against Corruption, Geoffrey Watson SC, declared theatrically at the opening of the inquiry into the grant of a coal licence at Mount Penny in 2012. A decade later, the NSW supreme court has found the grant of the controversial coal exploration licence in the Bylong Valley was the result of a criminal conspiracy that resulted in the Obeid family making at least $30m. The conviction of former Labor power broker Eddie Obeid, 77, his son Moses, 51, and the former mineral resources minister Ian Macdonald brings to an end one of the most sordid and extraordinary sagas in NSW politics. The trio now each face up to seven years in jail after being convicted of a conspiracy to wilfully commit misconduct in public office. 2 Justice Elizabeth Fullerton found they had engaged in a conspiracy which involved Macdonald using his position as Labor resources minister in 2008 to influence the creation of a valuable coal exploration licence over land owned by the Obeid family and several associates.