Federal Court of Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45Th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief Lists

Barton Deakin Brief: Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief lists individuals and institutions on Twitter relevant to policy and political developments in the federal government domain. These institutions and individuals either break policy-political news or contribute in some form to “the conversation” at national level. Being on this list does not, of course, imply endorsement from Barton Deakin. This Brief is organised by categories that correspond generally to portfolio areas, followed by categories such as media, industry groups and political/policy commentators. This is a “living” document, and will be amended online to ensure ongoing relevance. We recognise that we will have missed relevant entities, so suggestions for inclusions are welcome, and will be assessed for suitability. How to use: If you are a Twitter user, you can either click on the link to take you to the author’s Twitter page (where you can choose to Follow), or if you would like to follow multiple people in a category you can click on the category “List”, and then click “Subscribe” to import that list as a whole. If you are not a Twitter user, you can still observe an author’s Tweets by simply clicking the link on this page. To jump a particular List, click the link in the Table of Contents. Barton Deakin Pty. Ltd. Suite 17, Level 2, 16 National Cct, Barton, ACT, 2600. T: +61 2 6108 4535 www.bartondeakin.com ACN 140 067 287. An STW Group Company. SYDNEY/MELBOURNE/CANBERRA/BRISBANE/PERTH/WELLINGTON/HOBART/DARWIN -

Scheme Booklet Registered with Asic

QMS Media Limited 214 Park Street South Melbourne, VIC 3205 T +61 3 9268 7000 www.qmsmedia.com ASX Release 13 December 2019 SCHEME BOOKLET REGISTERED WITH ASIC QMS Media Limited (ASX:QMS) refers to its announcement dated 12 December 2019 in which it advised that the Federal Court had made orders approving: • the dispatch of a Scheme Booklet to QMS shareholders in relation to the previously announced Scheme of Arrangement with Shelley BidCo Pty Ltd, an entity controlled by Quadrant Private Entity and its institutional partners (Scheme); and • the convening of meetings of QMS shareholders to consider and vote on the Scheme. The Scheme Booklet has been registered today by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. A copy of the Scheme Booklet, including the Independent Expert's Report and the notices of the Scheme Meetings, is attached to this announcement and will be dispatched to QMS' shareholders before Thursday 19 December 2019. Key events and indicative dates The key events (and expected timing of these) in relation to the approval and implementation of the Scheme are as follows: Event Date Scheme Booklet dispatched to QMS shareholders Before Thursday 19 December 2019 General Scheme Meeting 10.00am on Thursday 6 February 2020 Rollover Shareholders Scheme Meeting Thursday 6 February (immediately following the General Scheme Meeting) Second Court Hearing Monday 10 February 2020 Effective Date Tuesday 11 February 2020 Scheme Record Date 5.00pm on Friday 14 February 2020 Implementation Date Friday 21 February 2020 Note: All dates following the date of the General Scheme Meeting and the Rollover Shareholders Scheme Meeting are indicative only and, among other things, are subject to all necessary approvals from the Court and any other regulatory authority and satisfaction or (if permitted) waiver of all conditions precedent in the Scheme Implementation Deed. -

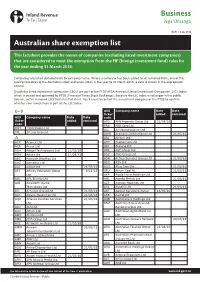

Australian Share Exemption List

Business Ngā Ūmanga IR871 | June 2016 Australian share exemption list This factsheet provides the names of companies (excluding listed investment companies) that are considered to meet the exemption from the FIF (foreign investment fund) rules for the year ending 31 March 2016. Companies are listed alphabetically by company name. Where a company has been added to, or removed from, one of the qualifying indices of the Australian stock exchange (ASX) in the year to 31 March 2016, a date is shown in the appropriate column. Qualifying listed investment companies (LICs) are part of the FTSE AFSA Australia Listed Investment Companies (LIC) Index which is owned and operated by FTSE (Financial Times Stock Exchange). Because the LIC index is no longer in the public domain, we’ve removed LICs from this factsheet. You’ll need to contact the investment company or the FTSE to confirm whether your investment is part of the LIC Index. 0–9 ASX Company name Date Date ticker added removed ASX Company name Date Date code ticker added removed APD APN Property Group Ltd 21/03/16 code ARB ARB Corp Ltd ONT 1300 Smiles Ltd ALL Aristocrat Leisure Ltd 3PL 3P Learning Ltd AWN Arowana International Ltd 21/03/16 A ARI Arrium Ltd ACX Aconex Ltd AHY Asaleo Care Ltd ACR Acrux Ltd AIO Asciano Ltd ADA Adacel Technologies Ltd 21/03/16 AFA ASF Group Ltd ADH Adairs Ltd 21/09/15 ASZ ASG Group Ltd ABC Adelaide Brighton Ltd ASH Ashley Services Group Ltd 21/03/16 AHZ Admedus Ltd ASX ASX Ltd ADJ Adslot Ltd 21/03/16 AGO Atlas Iron Ltd 21/03/16 AFJ Affinity Education Group 2/12/15 -

Framing the NBN: an Analysis of Newspaper Representations

Framing the NBN: An Analysis of Newspaper Representations Rowan Wilken, Swinburne University of Technology Jenny Kennedy, University of Melbourne Michael Arnold, University of Melbourne Martin Gibbs, University of Melbourne Bjorn Nansen, University of Melbourne Abstract The National Broadband Network (NBN), Australia’s largest public infrastructure project, was initiated to deliver universal access to high-speed broadband. Since its announcement, the NBN has attracted a great deal of media coverage, coupled with at times divisive political debate around delivery models, costs and technologies. In this article we report on the results of a pilot study of print media coverage of the NBN. Quantitative and qualitative content analysis techniques were used to examine how the NBN was represented in The Age and The Australian newspapers during the period from 1 July 2008 to 1 July 2013. Our findings show that coverage was overwhelmingly negative and largely focused on the following: potential impacts on Telstra; lack of a business plan, and of cost-benefit analysis; problems with the rollout; cost to the federal budget; and implications for business stakeholders. In addition, there were comparatively few articles on potential societal benefits, applications and uses, and, socio-economic implications. Keywords: National Broadband Network, media representations, The Age, The Australian, newspaper coverage, content analysis Introduction The success of the National Broadband Network (NBN) in fulfilling its ambition to provide high-speed broadband to every business and household in the country, grow the digital economy, and support digital inclusion will be shaped by how it is understood, adopted, and appropriated by end-users. Since the project was announced on 7 April 2009 by the then- Labor Federal Government, the NBN has attracted a great deal of media coverage, coupled with, at times, divisive political debate around the model, costs and technology best fit for purpose. -

Fairfax Media’S Digital Transformation

Case Study Cloudinary Delivers Simplified Image Management Workflow for Fairfax Media’s Digital Transformation “Cloudinaryhasanumberofcustomersthatweconsiderpeers,sowefeltconfidentinits capabilities and ability to scale to support our reader base. In addition, Cloudinary offered functionality that addressed our need to deliver content to different devices, across various channels, as well as enabling us to render images dynamically to support different image formats or aspect ratios in the future.” –Damian Cronan, CTO, Fairfax Media Solution The Cloudinary API enabled dynamic URL-based manipulations to original high-quality images, eliminating the need for the editorial team to manually create and store multiple variants of every image and streamlining the publishing workflow. Results 25% Reductioninfilesize LEADING Three millionimagesoptimized for performance MULTI-PLATFORM MEDIA COMPANY Faster time to market with improved productivity – both for the engineering team and editorial staff Get started for free: www.cloudinary.com © 2018 Cloudinary. All rights reserved. Case Study Company Fairfax Media Limited [ASX:FXJ] is one of the largest media companies in Australia and New Zealand that engages audiencesandcommunitiesviaprintanddigitalmedia.ItincludesrecognizablemastheadsincludingThe Australian Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. Fairfax Media operates numerous news and information websites, as well as tablet and smartphone apps, for online news sites. The Challenge: Future-Proof Image Management In2016,FairfaxMediabeganawide-rangingdigitaltransformationofitsnewsorganization,whichincludedstreamlining -

Privacy - Fairfax Media Limited

Privacy - Fairfax Media Limited PRIVACY You have come through to this page from a website which is published by a subsidiary of Fairfax Media Limited. In this policy, "us", "we" or "our" means Fairfax Media Limited (ABN 15 008 663 161) and its related bodies corporate, partnerships and joint venture entities. This policy sets out: • what is considered personal information; • what personal information we collect and hold; • how we collect, hold, use or disclose personal information; • the purposes for which we collect personal information; • what happens if we are not able to collect personal information; • how to seek access to and correct your personal information; • whether we disclose personal information outside Australia; and • how to contact us. We are bound by the Australian Privacy Principles contained in the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (subject to exemptions that apply to us under that Act). However, due to the nature of some of our business activities, from time to time, we will handle personal information relying on the media exemption in the Act where appropriate. Where we do so, we will ensure that we comply with the Australian Press Council Privacy Standards. We may also rely on related bodies corporate, employee records and other exemptions in the Act. If you require more information on the collection and use of personal information in the course of journalism, please visit the Australian Press Council Privacy Standards at www.presscouncil.org.au/privacy-principles. We may, from time to time, review and update this policy, including taking account of new or amended laws, new technology and/or changes to our operations. -

2020 Half Year Results Announcement

26 February 2020 ASX Markets Announcement Office ASX Limited 20 Bridge Street Sydney NSW 2000 2020 HALF YEAR RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT Attached is a copy of the ASX release relating to the 2020 Half Year Financial Results for Nine Entertainment Co. Holdings Limited Rachel Launders Company Secretary Authorised for release: Nine Board sub-committee Further information: Nola Hodgson Victoria Buchan Head of Investor Relations Director of Communications +61 2 9965 2306 +61 2 9965 2296 [email protected] [email protected] NINE ENTERTAINMENT CO. FY20 INTERIM RESULTS 26 February 2020: Nine Entertainment Co. (ASX: NEC) has released its H1 FY20 results for the 6 months to December 2019. On a Statutory basis, pre Specific Items, on Revenue of $1.2b, Nine reported Group EBITDA of $251m, and a Net Profit After Tax of $114m. Post Specific Items, the Statutory Net Profit was $102m. These numbers are stated excluding Discontinued Businesses. On a pre AASB16 and Specific Item basis, Nine reported Group EBITDA of $231m, down 8% on the Pro Forma results in H1 FY19 for its Continuing Businesses. On the same basis, Net Profit After Tax and Minority Interests was $115m, down 9%. Key takeaways include: • Strong growth from digital video businesses o $35m EBITDA improvement at Stan1, with subscribers exceeding 1.8m o 65% growth in EBITDA at 9Now1, with market leading BVOD share of ~50% o Further investment in 9Now to accelerate growth into the broader digital video market • Result was heavily impacted by challenging cycles o Broad based ad market weakness including a 7% decline in Metro FTA revenues o Housing market softness impacting Domain’s residential listing volumes • Stability in Metro Media earnings1 • Synergies of $9m identified following completion of the Macquarie Media acquisition • Nine expects FY20 EBITDA at a similar level to FY191 1 like-basis, pre AASB16 Hugh Marks, Chief Executive Officer of Nine Entertainment Co. -

Chapter 3 Section 5

SECTION 5: CHINA’S DOMESTIC INFORMATION CONTROLS, GLOBAL MEDIA INFLUENCE, AND CYBER DIPLOMACY Key Findings • China’s current information controls, including the govern- ment’s new social credit initiative, represent a significant es- calation in censorship, surveillance, and invasion of privacy by the authorities. • The Chinese state’s repression of journalists has expanded to target foreign reporters and their local Chinese staff. It is now much more difficult for all journalists to investigate politically sensitive stories. • The investment activities of large, Chinese Communist Par- ty-linked corporations in the U.S. media industry risk under- mining the independence of film studios by forcing them to consider self-censorship in order to gain access to the Chinese market. • China’s overseas influence operations to pressure foreign media have become much more assertive. In some cases, even without direct pressure by Chinese entities, Western media companies now self-censor out of deference to Chinese sensitivity. • Beijing is promoting its concept of “Internet sovereignty” to jus- tify restrictions on freedom of expression in China. These poli- cies act as trade barriers to U.S. companies through both cen- sorship and restrictions on cross-border data transfers, and they are fundamental points of disagreement between Washington and Beijing. • In its participation in international negotiations on global Inter- net governance, norms in cyberspace, and cybersecurity, Beijing seeks to ensure continued control of networks and information in China and to reduce the risk of actions by other countries that are not in its interest. Fearing that international law will be used by other countries against China, Beijing is unwilling to agree on specific applications of international law to cyberspace. -

Substantial Holding Notice

604 page 1/3 15 July 2001 Form 604 Corporations Act 2001 Section 671B Notice of change of interests of substantial holder To Company Name/Scheme Macquarie Media Limited ACN/ARSN ACN 063 906 927 1. Details of substantial holder (1) Name Nine Entertainment Co. Holdings Limited (Nine) and each of the entities set out in Annexure A ACN/ARSN (if applicable) ACN 008 663 161 This notice is given by Nine on behalf of itself, Fairfax Media Limited (Fairfax) and each of the entities set out in Annexure A (each a Nine Group Company and together, the Nine Group). There was a change in the interests of the 30 / 08 / 2019 substantial holder on This notice is given under section 671B(1)(c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act). The previous notice was given to the company on 10 / 12 / 2018 The previous notice was dated 10 /12 / 2018 2. Previous and present voting power The total number of votes attached to all the voting shares in the company or voting interests in the scheme that the substantial holder or an associate (2) had a relevant interest (3) in when last required, and when now required, to give a substantial holding notice to the company or scheme, are as follows: Previous notice Present notice Class of securities (4) Person’s votes Voting power (5) Person’s votes Voting power (5) 54.4% (based on 54.5% (based on Fully paid ordinary shares 171,204,556 93,196,512 171,002,774 ordinary shares 93,196,512 (Shares) ordinary shares on on issue) issue) 3. -

Chronology of Recent Events

AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 34 September 2005 Compiled for the ANHG by Rod Kirkpatrick, 13 Sumac Street, Middle Park, Qld, 4074. Ph. 07-3279 2279. E-mail: [email protected] 34.1 COPY DEADLINE AND WEBSITE ADDRESS Deadline for next Newsletter: 30 November 2005. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] The Newsletter is online through the “Publications” link of the University of Queensland’s School of Journalism & Communication Website at www.uq.edu.au/journ-comm/ and through the ePrint Archives at the University of Queensland at http://eprint.uq.edu.au/) CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS: METROPOLITAN 34.2 THE LEAVING OF LACHLAN Lachlan Murdoch has reignited interest in newspaper dynasties. Young Warwick Fairfax destroyed what his ancestors had built up in Sydney, mainly, over 150 years (well, about six weeks short of that time). Cameron O‘Reilly departed the family newspaper fold when chief executive officer of APN. Lachlan Murdoch, mentioned as a possible successor to his father at the helm of the family‘s worldwide media enterprise, has departed News Corporation‘s executive ranks at age 33 (the resignation as deputy chief operating officer took effect on 31 August). He announced that he would return to Australia to live with wife Sarah and son Kalan. The family has been living in New York City, but they have paid $7 million for a house at Bronte Beach, Sydney. Born in London, Lachlan Murdoch began working for News in the press hall of the Daily Mirror in Sydney. He graduated from Princeton University and began his executive career at the age of 21 as general manager of Queensland Newspapers Pty Ltd before being given responsibility for all of News‘s operations in Australia. -

Fairfax Media Nz

FAIRFAXFAIRFAX MEDIAMEDIA NZ:NZ: PAVINGPAVING THETHE ROADROAD FORFOR AA DIGITALDIGITAL FUTUREFUTURE New Zealand’s largest media company Fairfax NZ reaches 3.5 million New Zealanders every month (88% of population) via its digital and print brands FY18-21 Key Priorities 1 2 3 Grow engaged Diversify with Extend the and high value new digital runway for our audiences products and print products services ARPU Model - the Engine of Our Strategy Create premium products and new businesses Payers Subscriptions Selling our audience things E-Commerce & Transactions Retail, offers, coupons, vouchers Convert, engage Authenticated Audience and strengthen loyalty Audience targeting, data products, insights, content & audience partnerships Attract, acquire & Mass Audience develop our audience Display advertising, basic content marketing Growing Mass Audience How? Successes? Monthly audiences → Best coverage of major events 1.47m → 2.07m → Most comprehensive regional coverage Monthly volume → Social/SEO optimisation of stories 170m Pls → 198m Pls → Reticulate traffic Daily audiences 524,000 → 1.1m Attract, acquire & Mass Audience develop our 93% audience Display advertising, basic content marketing KPEX - Monetising MassMass AudienceAudience KPEX Monthly Revenue Growing Authenticated Audience How? Successes? → Develop capabilities in identity Stuff memberships* 104,000 → 960,000 and data management → Incentivise our audiences to sign Neighbourly memberships up or declare their data 62,000 → 500,000 Convert, engage Authenticated Audience and strengthen -

Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy Volume 8

Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy Volume 8 Issue 4 December 2020 Publisher: Telecommunications Association Inc. ISSN 2203-1693 Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy JTDE Volume 8, Number 4, December 2020 Table of Contents Editorial Ideology-Driven Telecommunications Market Leads to a Second-Rate Outcome ii Mark A Gregory Public Policy Should TV Move? 1 Giles Tanner, Jock Given On Australia’s Cyber and Critical Technology International Engagement Strategy Towards 6G 127 David Soldani The NBN Futures Forum: Towards a National Broadband Strategy for Australia, 2020-2030 180 Leith H. Campbell Special Interest Paper Towards a National Broadband Strategy for Australia, 2020-2030 192 Jim Holmes, John Burke, Leith Campbell, Andrew Hamilton Digital Economy Gap between Regions in the Use of E-Commerce by MSEs 37 Ida Busnetti, Tulus Tambunan Tax Risk Assessment and Assurance Reform in Response to the Digitalised Economy 96 Helena Strauss, Tyson Fawcett, Prof. Danie Schutte Review A Review of Current Machine Learning Approaches for Anomaly Detection in Network Traffic 64 Wasim A. Ali, Manasa K. N, Mohammed Fadhel Aljunid, Dr Malika Bendechache, Dr P. Sandhya History of Australian Telecommunications The Bellenden Ker Television Project 159 Simon Moorhead Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, ISSN 2203-1693, Volume 8 Number 4 December 2020 Copyright © 2020 i Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy Ideology-Driven Telecommunications Market Leads to a Second-Rate Outcome Editorial Mark A. Gregory RMIT University Abstract: Papers in the December 2020 issue of the Journal include a discussion about the parlous state of television broadcasting in Australia, 6G and the future of the National Broadband Network.