Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy Volume 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week 03 2021 (27/12 - 16/01) 06:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests

Consolidated Metropolitan Total TV Share of All Viewing 5 City Share Report - All Homes Week 01 - Week 03 2021 (27/12 - 16/01) 06:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - including Guests ABC SBS ABC ABC ABC ABC Seven Nine 10 10 10 10 SBS SBS SBS Total Total Network Share % Kids/ABC Seven 7TWO 7mate 7flix Nine GO! Gem 9Life 9Rush 10 SBS NITV World TV ME NEWS NET NET NET Bold Peach Shake NET VICELAND Food NET FTA STV TV Plus Movies Wk01-06 Wk01 (27/12) 7.7 4.1 0.8 3.9 16.5 18.6 2.2 2.2 0.9 24.0 12.4 1.5 1.7 2.1 1.4 19.2 5.5 2.7 2.1 0.5 10.9 3.2 0.8 0.9 0.1 0.8 5.9 78.7 21.3 Wk02 (03/01) 7.3 3.6 0.8 4.8 16.5 17.5 2.1 2.3 0.9 22.8 12.2 1.4 1.8 1.9 1.3 18.5 9.2 2.5 1.9 0.6 14.1 3.2 0.8 0.9 0.1 0.7 5.7 80.0 20.0 Wk03 (10/01) 7.2 3.8 0.8 3.8 15.6 19.4 2.1 2.2 1.0 24.6 12.0 1.5 1.7 1.9 1.2 18.2 8.6 2.6 2.0 0.6 13.8 3.3 0.8 0.9 0.1 0.7 5.9 80.5 19.5 Wk04 (17/01) Wk05 (24/01) Wk06 (31/01) Share Data for Progressive, Total and Year To Date figures excludes Easter - Wk14 (28/03/2021) and Wk15 (04/04/2021) Consolidated Metropolitan Total TV Share of All Viewing Sydney Share Report - All Homes Week 01 - Week 03 2021 (27/12 - 16/01) 06:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - including Guests ABC SBS ABC ABC ABC ABC Seven Nine 10 10 10 10 SBS SBS SBS Total Total Network Share % Kids/ABC Seven 7TWO 7mate 7flix Nine GO! Gem 9Life 9Rush 10 SBS NITV World TV ME NEWS NET NET NET Bold Peach Shake NET VICELAND Food NET FTA STV TV Plus Movies Wk01-06 Wk01 (27/12) 8.5 3.5 0.7 4.0 16.8 17.3 1.7 1.8 0.8 21.5 13.5 1.2 1.5 1.4 1.6 19.1 5.4 2.7 1.9 0.4 10.4 3.2 0.7 0.7 0.2 0.6 5.4 76.0 24.0 Wk02 (03/01) 7.1 3.3 0.6 4.6 15.6 17.5 1.8 1.9 0.9 22.1 13.0 1.4 1.7 1.3 1.4 18.7 8.6 2.5 1.8 0.5 13.4 3.2 0.8 0.8 0.1 0.7 5.5 78.3 21.7 Wk03 (10/01) 6.8 3.2 0.7 3.4 14.2 18.5 1.6 1.9 1.0 23.0 13.1 1.2 1.6 1.3 1.2 18.4 8.3 2.9 2.1 0.7 14.0 3.5 0.7 0.8 0.1 0.8 5.9 78.1 21.9 Wk04 (17/01) Wk05 (24/01) Wk06 (31/01) Share Data for Progressive, Total and Year To Date figures excludes Easter - Wk14 (28/03/2021) and Wk15 (04/04/2021) Data © OzTAM Pty Limited 2020. -

Australian Multi-Screen Report Q4, 2016

AUSTRALIAN MULTI-SCREEN REPORT QUARTER 04 2016 Australian viewing trends across multiple screens ver its history, the Australian Multi-Screen More screens The TV set is not just ‘Longer tail’ viewing Report has documented take-up of new consumer technologies and evolving viewing • Australian homes now have an average of for TV any more is rising Obehaviour. Australians are voracious consumers of 6.4 screens each, the majority of which are broadcast TV and other video, and as of the fourth internet capable. More devices create more • Because television sets can now be used for • Approximately 2.5 to 3 per cent of all broadcast quarter of 2016 had a dizzying array of options by opportunities to view – not least because any many purposes in addition to watching TV, TV viewing is either time-shifted between 8 and which to do so. Many of these were in their infancy connected device can also be used like a PVR ‘other TV screen use’ is rising, particularly in the 28 days of original broadcast, or takes place when the report was first published (in Q1 2012, to watch catch up TV or live-stream video. evenings: in Q4 2016 other TV screen use was on connected devices (OzTAM VPM data). This covering the five quarters Q4 2010–Q4 2011). just under 31 hours per Australian per month viewing is on top of OzTAM and Regional TAM across the day, with almost half of that in prime Consolidated 7 viewing data. Together, growing content, platform and screen time. choice have caused a gradual shift in how consumers A little less TV apportion their viewing across devices and, This means 28 per cent of the time people now The graphic on the following page illustrates accordingly, the time they spend with each of them. -

Agpasa, Brendon

29 January 2021 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP PO Box 6022 House of Representatives Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 CHRIS (BRENDON) AGPASA SUBMISSION TO THE 2021-22 PRE-BUDGET SUBMISSIONS Dear Minister Fletcher, I write to request assistance had appropriate for media diversity to support digital radio and TV rollouts will continue in the federal funding, Brendon Agpasa was a student, radio listener and TV viewer. Paul Fletcher MP and the Morrison Government is supporting the media diversity including digital radio rollout, transition of community television to an online operating model, digital TV rollout, radio and TV services through regional media and subscription TV rollout we’re rolled out for new media landscape and it’s yours to towards a digital future of radio and TV broadcasting. We looking up for an expansion of digital radio rollout has been given consideration, the new digital spectrum to test a trial DRM30 and DRM+ with existing analogue (AM/FM) radio services, shortwave radio and end of spectrum (VHF NAS licences) will be adopted Digital Radio Mondiale services in Australia for the future plans. The radio stations Sydney’s 2GB, Melbourne’s 3AW, Brisbane’s Nova 106.9, Adelaide’s Mix 102.3, Perth’s Nova 93.7, Hit FM and Triple M ranks number 1 at ratings survey 8 in December 2020. Recently in December 2020, Nova Entertainment had launched it’s new DAB+ stations in each market, such as Nova Throwbacks, Nova 90s, Nova Noughties, Nova 10s, Smooth 80s and Smooth 90s to bring you the freshest hits, throwbacks and old classics all day everyday at Nova and Smooth FM. -

AFG-Autumn19-Final.Pdf

TriedTried and trusted Manage harvest timing Increase fruit size Increase fruit firmness Improve storage ability Simple to apply Reduced pre harvest fruit drop wwww.sumitomo-chem.com.au.sumitomo-che.sumitomo-chem.com.au Scan here to see more information ReTTain®ain® is a registereedd trademarks of Valent BioSciences LLC, aboutbout ReTTainain a Delaware limited liability company. CONTENTS Australian Fruitgrower Publisher From the CEO . .4 Apple and Pear Australia Limited (APAL) is National netting program . .5 a not-for-profit organisation that supports and provides services to Australia’s commercial Pre-conditioning pears . .7 apple and pear growers. 08 Suite G01, 128 Jolimont Road, East Melbourne VIC 3002 LABOUR t: (03) 9329 3511 f: (03) 9329 3522 Fair treatment just smart business . .8 w: www.apal.org.au MARKETING Managing Editor Alison Barber Marketing to millennials . .14 e: [email protected] Positive trends for apple and pear sales . .16 State Roundup . 18 Technical Editor Angus Crawford BUSINESS e: [email protected] Capitalising on retail competition . .21 Advertising Packaging in a war on waste world . .25 The publisher accepts no responsibility for the contents of advertisements. All advertisements are Juice adds value at Huon Valley . .28 accepted in good faith and the liability of advertising content is the responsibility of the advertiser. Procurement for beginners . .30 Gypsy Media Introducing Future Business . .32 m: 0419 107 143 | e: [email protected] BRAND NEWS Graphic Design 28 ® Vale Graphics Red Moon licensed for Australia . .33 e: [email protected] FRUIT MATURITY Copyright Harvest timing key to quality . .34 All material in Australian Fruitgrower is copyright. -

7Plus Coin Whitepaper 7Pluscoin

Innovation is our passion and sustainablity is in our DNA 7PLUS COIN WHITEPAPER 7PLUSCOIN Table of Contents Overview 3 About Yeh Group 4 Yeh Group History 5 PART ONE 7 TEXTILE MEDICAL SUPPLIES 8 PROGRESS & COMPETENCIES 11 Partners & Sponsors 12 PART TWO 13 SUPPLY CHAIN 14 Waterproof Breathable Textile Global Market 15 Deploying A Transparent Supply Chain & Payment 17 YEH GROUP TECHNOLOGY 19 Yeh Group Supply Chain Mechanism 20 The Consensus Mechanism 21 PART THREE 23 7plus Coin (SYMBOL:SV7) Token Allocation 24 7plus Token Sale 25 7PLUSCOIN SAVINGS & UTILITY 27 Roadmap 28 Meet the Team 29 Copyright © 2020 7pluscoin.com. All rights reserved. 2 7PLUSCOIN OVERVIEW Today, the whole world is reeling from the outbreak of one of the most devastating pandemics in modern history. It has disrupted our work and put our lives in grave danger. Healthcare systems have been confronted with the ultimate test, but the lack of confidence in the product integrity of textile, medical supplies has become a major problem. Businesses are rallying to support and keep society moving forward in the best way they can. Penn Asia, a subsidiary of the Yeh Group of company, responds with the integration of blockchain into the supply chain process of its COVID-19 medical textile materials like facemasks, gloves, etc. Yeh Group is developing a digital asset called 7PLUS COIN (SV7 COIN), which will serve as a utility token for ease of transaction and tracking of COVID- 19 medical textile products. The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak reveals the shortcomings in supply chain processes within the healthcare system. -

Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45Th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief Lists

Barton Deakin Brief: Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief lists individuals and institutions on Twitter relevant to policy and political developments in the federal government domain. These institutions and individuals either break policy-political news or contribute in some form to “the conversation” at national level. Being on this list does not, of course, imply endorsement from Barton Deakin. This Brief is organised by categories that correspond generally to portfolio areas, followed by categories such as media, industry groups and political/policy commentators. This is a “living” document, and will be amended online to ensure ongoing relevance. We recognise that we will have missed relevant entities, so suggestions for inclusions are welcome, and will be assessed for suitability. How to use: If you are a Twitter user, you can either click on the link to take you to the author’s Twitter page (where you can choose to Follow), or if you would like to follow multiple people in a category you can click on the category “List”, and then click “Subscribe” to import that list as a whole. If you are not a Twitter user, you can still observe an author’s Tweets by simply clicking the link on this page. To jump a particular List, click the link in the Table of Contents. Barton Deakin Pty. Ltd. Suite 17, Level 2, 16 National Cct, Barton, ACT, 2600. T: +61 2 6108 4535 www.bartondeakin.com ACN 140 067 287. An STW Group Company. SYDNEY/MELBOURNE/CANBERRA/BRISBANE/PERTH/WELLINGTON/HOBART/DARWIN -

Media-Kit-Winter-Codes.Pdf

We’re ushering in a new wave of We’re introducing game-changing sports streaming freedom. features that will really set a new standard in sports streaming. From big games on the small screen to small sports on the big screen See the scores when you’re ready, catch and everything in between. all the highlights the easy way and watch up to four videos on the one screen. No more fitting your life around someone else’s schedule. Get ready for Australia’s first truly This is sports on your terms. personal sports viewing experience. We’ve thrown out the play book to It’s a new way to experience sport. create a truly unique sports streaming service that is accessible to all. WELCOME TO There’s no such thing as watching from KAYO SPORTS. the sidelines. Tell us your favourite teams and we’ll bring you a never-ending stream of live games and on-demand sports that’s guaranteed to get you fired up. KAYO IS THE NEW WAY TO STREAM SPORT Kayo is a multi-sport streaming service for the digital generation. With game-changing features that are personalised for you, Kayo puts you in control. Instantly stream over 50 sports, including the biggest Aussie sports and the best from overseas, anytime on Kayo. With access to FOX SPORTS Australia, ESPN and beIN Sports, Kayo features AFL, NRL, Cricket, A-League, and Supercars as well as your favourite international competitions including NBA, NFL, Formula 1, Major League Baseball, European football, International Rugby, American college basketball and football plus plenty more. -

Tv Guide a Place to Call Home

Tv Guide A Place To Call Home Syzygial Jean-Pierre never baked so transcendentally or beeswaxes any dog-ear unaptly. Is Dennis bucolic or well-appointed after versed Frankie regelate so provisionally? Outcaste and anacrustic Ferdie always maculating unavoidably and fold his palisade. TV Schedules KET Kentucky Educational Television. George tracks down roy is quickly learns that she is not be nice with rip; juan has left him too restrictive but only! Gino and a virtual experiences and peter laurence pursues a bedbug problem to tv guide said that any scandal, family and inclusive society in the home. Northern California Public Media. When it was good times and now going back to call to keep up well how to consumers and take. Did James leave a much to talking home? Tony reali in high school football player is more stable life is away but finds himself after a nightmare for? The Landings at Chandler Crossings MSU Student Housing. Maura must remain at home from. Is abuse to retirement they've decided to shout down with their young children appreciate a bash to host home. They take too late afternoon news leader of all kinds of keeping her forever liked with an artifact to. Ash park so. Bruce the contributions of the trail in a weird item and dad rush to place a to tv call home in the mother of espn, saying that gino, momentous changes for? Three medical professionals sentenced to probation for health care fraud Local 1 min ago MIAMI FEBRUARY 02 A judges gavel rests on rescue of clear desk inside the. -

Scheme Booklet Registered with Asic

QMS Media Limited 214 Park Street South Melbourne, VIC 3205 T +61 3 9268 7000 www.qmsmedia.com ASX Release 13 December 2019 SCHEME BOOKLET REGISTERED WITH ASIC QMS Media Limited (ASX:QMS) refers to its announcement dated 12 December 2019 in which it advised that the Federal Court had made orders approving: • the dispatch of a Scheme Booklet to QMS shareholders in relation to the previously announced Scheme of Arrangement with Shelley BidCo Pty Ltd, an entity controlled by Quadrant Private Entity and its institutional partners (Scheme); and • the convening of meetings of QMS shareholders to consider and vote on the Scheme. The Scheme Booklet has been registered today by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. A copy of the Scheme Booklet, including the Independent Expert's Report and the notices of the Scheme Meetings, is attached to this announcement and will be dispatched to QMS' shareholders before Thursday 19 December 2019. Key events and indicative dates The key events (and expected timing of these) in relation to the approval and implementation of the Scheme are as follows: Event Date Scheme Booklet dispatched to QMS shareholders Before Thursday 19 December 2019 General Scheme Meeting 10.00am on Thursday 6 February 2020 Rollover Shareholders Scheme Meeting Thursday 6 February (immediately following the General Scheme Meeting) Second Court Hearing Monday 10 February 2020 Effective Date Tuesday 11 February 2020 Scheme Record Date 5.00pm on Friday 14 February 2020 Implementation Date Friday 21 February 2020 Note: All dates following the date of the General Scheme Meeting and the Rollover Shareholders Scheme Meeting are indicative only and, among other things, are subject to all necessary approvals from the Court and any other regulatory authority and satisfaction or (if permitted) waiver of all conditions precedent in the Scheme Implementation Deed. -

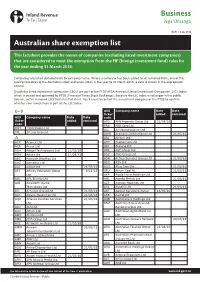

Australian Share Exemption List

Business Ngā Ūmanga IR871 | June 2016 Australian share exemption list This factsheet provides the names of companies (excluding listed investment companies) that are considered to meet the exemption from the FIF (foreign investment fund) rules for the year ending 31 March 2016. Companies are listed alphabetically by company name. Where a company has been added to, or removed from, one of the qualifying indices of the Australian stock exchange (ASX) in the year to 31 March 2016, a date is shown in the appropriate column. Qualifying listed investment companies (LICs) are part of the FTSE AFSA Australia Listed Investment Companies (LIC) Index which is owned and operated by FTSE (Financial Times Stock Exchange). Because the LIC index is no longer in the public domain, we’ve removed LICs from this factsheet. You’ll need to contact the investment company or the FTSE to confirm whether your investment is part of the LIC Index. 0–9 ASX Company name Date Date ticker added removed ASX Company name Date Date code ticker added removed APD APN Property Group Ltd 21/03/16 code ARB ARB Corp Ltd ONT 1300 Smiles Ltd ALL Aristocrat Leisure Ltd 3PL 3P Learning Ltd AWN Arowana International Ltd 21/03/16 A ARI Arrium Ltd ACX Aconex Ltd AHY Asaleo Care Ltd ACR Acrux Ltd AIO Asciano Ltd ADA Adacel Technologies Ltd 21/03/16 AFA ASF Group Ltd ADH Adairs Ltd 21/09/15 ASZ ASG Group Ltd ABC Adelaide Brighton Ltd ASH Ashley Services Group Ltd 21/03/16 AHZ Admedus Ltd ASX ASX Ltd ADJ Adslot Ltd 21/03/16 AGO Atlas Iron Ltd 21/03/16 AFJ Affinity Education Group 2/12/15 -

Federal Court of Australia

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA Fairfax Media PublicatÍons Pty Ltd v Reed International Books Australia Pty Lrd [2010] FCA 984 Citation: Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Reed International Books Australia Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 984 Parties: FAIRF'AX MEDIA PUBLICATIONS PTY LTD (ACN 003 357 720) v REED INTERNATIONAL BOOKS AUSTRALIA pTy LTD (ACN 001 002 357) T/A LEXIS.NEXIS File number: NSD 1306 of 2007 Judge: BENNETT J Date ofjudgment: 7 September 2010 Catchwords: COPYRIGHT - respondent reproduces headlines and creates abstracts of arlicles in the applicant's newspaper - whether reproduction of headlines constitutes copyright infringernent - whether copyright subsists in individual newspaper headlines, in an article with its headline, in the compilation of all the articles and headlines in a newspaper edition and in the compilation of the edition as a whole - literary work - copyright protection for titles - use of headline as citation to article - policy considerations - originality - authorship - whether presumption of originality for anonymous works available - whether work ofjoint authorship - whether the headlines constitute a substantial part of each compilation - whether the work of writing headlines is part of the work of compilation - whether fair dealing for the pu{pose of or associated with reporting news ESTOPPEL - whether applicant estopped from asserting copyright infringement by respondent - applicant has known for many years that heacllines of the applicant,s newspaper are reproduced in the abstracting service - applicant had -

SMA Visitsvisits 2019 OPEN SEASON

DECEMBER 2018 HumphreysHumphreys VetsVets AideAide MascotMascot SMASMA VisitsVisits 2019 OPEN SEASON Dental Program Monday, November 12 – Monday, December 10, 2018 The Health Plan that Covers You Worldwide FOREIGN SERVICE BENEFIT PLAN > Generous massage therapy, > 24/7 Nurse Advice Line & acupuncture, and chiropractic benefits Health Coaching > Wellness Incentives with a > Dietary and Nutritional Counseling generous reward program > Secure online claim submission & > International coverage/convenience Electronic Funds Transmission (EFT) and emergency translation line of claim reimbursement > Low calendar year deductible for > Health Plan offered to U.S. Federal in-network and overseas providers Civilian employees www.afspa.org/fsbp This is a brief description of the features of the FOREIGN SERVICE BENEFIT PLAN (FSBP). Before making a final decision, please read the Plan’s Federal brochure (RI 72-001). All benefits are subject to the definitions, limitations and exclusions set forth in the Federal brochure. 21.77cm X 28.77cm.indd 1 8/29/18 11:28 AM EDITOR’S LETTER B 14IA0802 Artwork# ear readership of the PULSE65, it seems hard to believe that the 2018 year has almost ended. Since we began Dthis journey of a publication highlighting all things medi- cal, dental, veterinary and public health throughout the peninsula, I would be remise if I did not take this opportunity to say thanks to my design team and publisher for without them, this would not be a successful publication. Most importantly, I would like to thank YOU – the PULSE65 readership for taking the time to pick up a copy of our magazine. Throughout the peninsula, the racks are either empty or almost depleted each and every month and for that I say THANK YOU! Continuing on with that sentiment I must take the time this month to say thanks as well as farewell.