Long-Running Drama in Theatre of Public Shame

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inaugural Speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith

Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author would like to thank officers from both Houses for their comments on a draft of this paper, in particular Stephanie Hesford and Jonathan Elliott from the Legislative Assembly and Stephen Frappell and Samuel Griffith from the Legislative Council. Thanks, too, to Lenny Roth and Greig Tillotson for their comments and advice. Any errors are the author’s responsibility. ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 978 0 7313 1900 8 May 2013 © 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior consent from the Manager, NSW Parliamentary Research Service, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament by Gareth Griffith NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Manager, Politics & Government/Law .......................................... (02) 9230 2356 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Acting Senior Research Officer, Law ............................................ (02) 9230 3085 Lynsey Blayden (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ................................................................. (02) 9230 3085 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Social Issues/Law ........................................... (02) 9230 2484 Jack Finegan (BA (Hons), MSc), Research Officer, Environment/Planning..................................... (02) 9230 2906 Daniel Montoya (BEnvSc (Hons), PhD), Research Officer, Environment/Planning ..................................... (02) 9230 2003 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics ...................................................... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. -

1. Gina Rinehart 2. Anthony Pratt & Family • 3. Harry Triguboff

1. Gina Rinehart $14.02billion from Resources Chairman – Hancock Prospecting Residence: Perth Wealth last year: $20.01b Rank last year: 1 A plunging iron ore price has made a big dent in Gina Rinehart’s wealth. But so vast are her mining assets that Rinehart, chairman of Hancock Prospecting, maintains her position as Australia’s richest person in 2015. Work is continuing on her $10billion Roy Hill project in Western Australia, although it has been hit by doubts over its short-term viability given falling commodity prices and safety issues. Rinehart is pressing ahead and expects the first shipment late in 2015. Most of her wealth comes from huge royalty cheques from Rio Tinto, which mines vast swaths of tenements pegged by Rinehart’s late father, Lang Hancock, in the 1950s and 1960s. Rinehart's wealth has been subject to a long running family dispute with a court ruling in May that eldest daughter Bianca should become head of the $5b family trust. 2. Anthony Pratt & Family $10.76billion from manufacturing and investment Executive Chairman – Visy Residence: Melbourne Wealth last year: $7.6billion Rank last year: 2 Anthony Pratt’s bet on a recovering United States economy is paying off. The value of his US-based Pratt Industries has surged this year thanks to an improving manufacturing sector and a lower Australian dollar. Pratt is also executive chairman of box maker and recycling business Visy, based in Melbourne. Visy is Australia’s largest private company by revenue and the biggest Australian-owned employer in the US. Pratt inherited the Visy leadership from his late father Richard in 2009, though the firm’s ownership is shared with sisters Heloise Waislitz and Fiona Geminder. -

Annual Report 2006–07

annual report 2006–07 CEDA Level 5, 136 Exhibition Street Melbourne 3000 Australia Telephone: (03) 9662 3544 Fax: (03) 9663 7271 Email: [email protected] Web: ceda.com.au About this publication Annual Report 2006–07 © CEDA 2007 ISSN 1832-8822 This publication is available on CEDA’s website: ceda.com.au For an emailed or printed copy, please contact the national office on 03 9662 3544 or [email protected] Design: Robyn Zwar Graphic Design Photography: Sean Davey/BRW, iStockphoto, Jason McCormack, Paul Lovelace Photography, Photonet, Yusuke Sato contents What is CEDA? ...............................................................2 Chairman’s report...........................................................4 CEO’s report...................................................................5 Review of operations......................................................6 Membership .............................................................7 Research ...............................................................12 Events.....................................................................16 International activity.................................................23 Communications ....................................................25 Governance..................................................................28 Concise financial report................................................34 Overview.................................................................35 Directors’ report ......................................................38 Income statement....................................................41 -

The Sydney Morning Herald's Linton Besser and the Incomparable

Exposed: Obeids' secret harbour deal Date May 19, 2012 Linton Besser, Kate McClymont The former ALP powerbroker Eddie Obeid hid his interests in a lucrative cafe strip. Moses Obeid. Photo: Kate Geraghty FORMER minister Eddie Obeid's family has controlled some of Circular Quay's most prominent publicly-owned properties by hiding its interests behind a front company. A Herald investigation has confirmed that Mr Obeid and his family secured the three prime cafes in 2003 and that for his last nine years in the upper house he failed to inform Parliament about his family's interest in these lucrative government leases. Quay Eatery, Wharf 5. Photo: Mick Tsikas For the first time, senior officials and former cabinet ministers Carl Scully and Eric Roozendaal have confirmed Mr Obeid's intervention in the lease negotiations for the quay properties, including seeking favourable conditions for the cafes, which the Herald can now reveal he then secretly acquired. Crucially, when the former NSW treasurer Michael Costa had charge of the waterfront, he put a stop to a public tender scheduled for 2005 that might have threatened the Obeids' control over two of the properties. Mr Obeid was the most powerful player inside the NSW Labor Party for the past two decades, and was described in 2009 by the deposed premier Nathan Rees as the party's puppet-master. Eddie Obeid. Photo: Jon Reid The Arc Cafe, Quay Eatery and Sorrentino, which are located in blue-ribbon positions on or next to the bustling ferry wharves at the quay, are all run by a $1 company called Circular Quay Restaurants Pty Ltd. -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

Political Briefings: - Barry O’Farrell MP, NSW Leader of the Opposition: Thursday 27Th May 2010

Political Briefings: - Barry O’Farrell MP, NSW Leader of the Opposition: Thursday 27th May 2010 1) Libertarian and Progressive Conservatism: Concept/Strategy as stated to Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs, Julie Bishop MP, re Chief of Staff emails in late 2009 for then Federal Leader of Opposition, Malcolm Turnbull MP. 2) Tailored Policies/Programmes: Obviously the Federal and NSW political, economic, social and cultural circumstances are different or at least not exactly the same. Sydney’s “regionalism” has historical peculiarities as the “founding city” of the nation. Sydney always looked to the Mother Country, UK, and its colonial “off-shoots: in Tasmania, Victoria, New Zealand and Queensland, and through them to the Pacific Islands in the South West Pacific. NSW was predominantly Free Trade in persepective rather than Protectionist as in Victoria. 3) Political Parties in New South Wales: The ALP – since Sir William McKell MP, Premier 1941-47 a) McKell to Renshaw - Premiers 1941-65 b) Wran and Unsworth – Premiers 1976-88 c) Carr to Keneally – Premiers 1995-2011 The Liberal Party – since Sir Robert Askin MP, Premier 1965-75 a) Pre WW11 – Bertram Stevens 1932-39 b) The Bob Askin years - a decade of alleged “corruption”. c) Greiner and Fahey – 1988-1995 4) Barry O’Farrell – State Leader of the Opposition: a) Comment by Nick Greiner: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/opinion/election-is-the-only-opinion-poll-that- matters/story-e6frg6zo-1225869365983 b) The Rudd/Abbott contest for PM -2010 c) Three/four terms of ‘Good” Liberal Party Government – 2011/27 5) ACCCI Interests a) NSW is “in” the Trade Business – Ministry for Foreign Economic Relations b) Greater Sydney as a World City – one Mayor, many Deputies. -

Paul O'grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus O

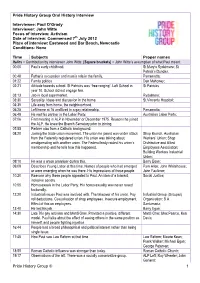

Pride History Group Oral History Interview Interviewee: Paul O’Grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus of interview: Activism Date of interview: Commenced 7th July 2012 Place of interview: Eastwood and Bar Beach, Newcastle Conditions: None Time Subjects Proper names Italics = Contribution by interviewer John Witte, [Square brackets] = John Witte’s assumption of what Paul meant. 00:00 Paul’s early childhood. St Mary’s Rydalmere; St Patrick’s Dundas; 00:48 Father’s occupation and mum’s role in the family. Parramatta; 01:22 Family politics. Dan Mahoney; 02:21 Attitude towards school. St Patricks was “free ranging”. Left School in St Patricks year 10. School did not engage him. 03:13 Job in local supermarket. Rydalmere; 03:30 Sexuality. Ideas and discussion in the home. St Vincents Hospital; 04:35 Life away from home, the neighbourhood. 05:25 Left home at 16 and lived in a gay relationship. Parramatta; 06:49 He met his partner in the Labor Party. Australian Labor Party; 07:06 First meeting in ALP in November or December 1975. Reasons he joined the ALP. He knew the Branch Secretary prior to joining. 07:55 Partner also from a Catholic background. 08:20 Joining the trade union movement. The union he joined was under attack Shop Branch, Australian from the Federally registered union. His union was talking about Workers’ Union; Shop amalgamating with another union. The Federal body raided his union’s Distributive and Allied membership and he tells how this happened. Employees Association; Building Workers Industrial Union; 09:10 He was a union organiser during this. -

Research Report on Trends in Police Corruption

COMMITTEE ON THE OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN AND THE POLICE INTEGRITY COMMISSION RESEARCH REPORT ON TRENDS IN POLICE CORRUPTION December 2002 COMMITTEE ON THE OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN AND THE POLICE INTEGRITY COMMISSION RESEARCH REPORT ON TRENDS IN POLICE CORRUPTION December 2002 Parliament House Macquarie Street Sydney 2000 Tel: (02) 9230 2737 Fax: (02) 9230 3309 ISBN 0 7347 6899 0 Table Of Contents COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP .........................................................................................................i CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD..........................................................................................................ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................iii INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE – A TYPOLOGY OF POLICE CORRUPTION........................................................ 3 1.1 A BRIEF REVIEW OF POLICING AND ETHICS LITERATURE.............................................................. 3 1.2 DEFINING POLICE CORRUPTION.............................................................................................. 6 1.3 ROTTEN APPLE VS ROTTEN BARREL ...................................................................................... 10 1.4 CYCLES OF CORRUPTION.................................................................................................... 12 1.5 CORRUPTION – AN ETHICAL OR ADMINISTRATIVE PROBLEM?.................................................... -

Neville Wran. Australian Biographical Monographs No. 5, by David Clune

158 Neville Wran. Australian Biographical Monographs No. 5, by David Clune. Cleveland (Qld): Connor Court Publishing, 2020. pp. 80, Paperback RRP $19.95 ISBN: 9781922449092 Elaine Thompson Former Associate Professor, University of New South Wales. It’s been many years since I’ve thought about Neville Wran, so I came to this monograph with an oPen mind, limited by two Personal judgements. The first was the belief that Wran was a giant of his time, a real leader and moderniser. The second was the tragedy (farce) of his last years. It was a reminder to us all that there are no guarantees that a great life will be rewarded with a kind death: for Neville Wran that was certainly not the case. Luckily, now with time we remember his leadershiP, his modernising Policies and his largely successful ability to dominate an extraordinarily Powerful Political Party with its deeP factions. David Clune’s monograph, through the use of first-hand materials and comments from Wran’s colleagues, takes us through Wran’s rise to Power, his successes as Premier and his fall via the web of corruPtion and scandal that ended his Premiership. Clune’s narrative is clear and remarkably free of value-judgements. It reminds us just how moribund the Politics and Parliament of NSW were at the time leading uP to Wran’s Government and of all the talent Wran brought with him, which transformed NSW Politics, Policy and Parliament. Of course, there were failures; things left incomPlete and the embedded corruPt culture of NSW Politics largely ignored. Nonetheless, in this monograph we gain a Picture of an extraordinary man leading Australia (via NSW) into the modern era. -

Legislative Council

22912 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday 19 May 2010 __________ The President (The Hon. Amanda Ruth Fazio) took the chair at 2.00 p.m. The President read the Prayers. APPROPRIATION (BUDGET VARIATIONS) BILL 2010 WEAPONS AND FIREARMS LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2010 Bills received from the Legislative Assembly. Leave granted for procedural matters to be dealt with on one motion without formality. Motion by the Hon. Tony Kelly agreed to: That the bills be read a first time and printed, standing orders be suspended on contingent notice for remaining stages and the second readings of the bills be set down as orders of the day for a later hour of the sitting. Bills read a first time and ordered to be printed. Second readings set down as orders of the day for a later hour. PRIVILEGES COMMITTEE Report: Citizen’s Right of Reply (Mrs J Passas) Motion by the Hon. Kayee Griffin agreed to: That the House adopt the report. Pursuant to standing orders the response of Mrs J. Passas was incorporated. ______ Reply to comments by the Hon Amanda Fazio MLC in the Legislative Council on 18 June 2009 I would like to reply to comments made by the Hon Amanda Fazio MLC on 18 June 2009 in the Legislative Council about myself. Ms Fazio makes two accusations, which adversely affect my reputation: That I am "an absolute lunatic"; and That apart from "jumping on the bandwagon of a genuine community campaign for easy access" at Summer Hill railway station, I did not have anything to do with securing the easy access upgrade at Summer Hill. -

Legislative Council

5243 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday 25 September 2002 ______ The President (The Hon. Dr Meredith Burgmann) took the chair at 11.00 a.m. The President offered the Prayers. DISTINGUISHED VISITORS The PRESIDENT: I welcome into the President's gallery the Ambassador for The Netherlands, Dr Hans Sondaal, and Mrs Els Sondaal and the Consul General of The Netherlands, Madelien de Planque. FARM DEBT MEDIATION AMENDMENT BILL CRIMES (ADMINISTRATION OF SENTENCES) FURTHER AMENDMENT BILL AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY SERVICES AMENDMENT (INTERSTATE ARRANGEMENTS) BILL Bills received and read a first time. Motion by the Hon. Michael Egan agreed to: That standing orders be suspended to allow the passing of the bills through all is remaining stages during the present or any one sitting of the House. LAND AND ENVIRONMENT COURT AMENDMENT BILL Message received from the Legislative Assembly agreeing to the Legislative Council's amendments. AUDIT OFFICE Report The President tabled, in accordance with the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, the performance audit report entitled "e-government: Electronic Procurement of Hospital Supplies" dated September 2002. Ordered to be printed. TABLING OF PAPERS The Hon. Carmel Tebbutt tabled the following papers: (1) Bank Mergers (Application of Laws) Act 1996—Treasurer's Report on the Statutory Five Year Review, dated September 2002. (2) Bank Mergers Act 1996—Treasurer's Report on the Statutory Report on the Statutory Five Year Review, dated September 2002. Ordered to be printed. BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE Withdrawal of Business Business of the House Notice of Motion No. 1, withdrawn by the Hon. Richard Jones. 5244 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL 25 September 2002 BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE Suspension of Standing and Sessional Orders Motion by the Hon. -

Trust and Political Behaviour Jonathan O’Dea1 Member for Davidson in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Trust and Political Behaviour Jonathan O’Dea1 Member for Davidson in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly INTRODUCTION: THE DECLINE IN TRUST Trust is the most important asset in politics. Trust can generate community and business confidence, leading to economic growth and improved political success for an incumbent government. The more a government is trusted, the more people and business will generally spend and invest, boosting the economy. People are also more likely to pay their taxes and comply with regulations if they trust government. Trust promotes a social environment of optimism, cohesion and national prosperity. When trust is lost, it is difficult to win back. Where it is eroded, a general malaise can develop that is destructive to the essential fabric of society and operation of democracy. Unfortunately, in Australia and internationally, there has been a growing erosion of trust in politicians and in politics. People are losing trust in institutions including governments, charities, churches, media outlets and big businesses. In a recent Essential Poll, 45 percent of those surveyed said they had no trust in political parties, 29 percent had no trust in state parliaments and 32 percent had no trust in federal Parliament.2 Since 1969, when Australians were first surveyed about their trust in politicians, the proportion of voters saying government in Australia could be trusted has fallen from 51 percent to just 26 percent in 2016, while the number of voters who believe ‘people in government look after themselves’ has increased from 49 percent to 75 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Australasian Study of Parliament Group Conference held in Brisbane on 18-20 July 2018.