Lecture 22: Bivariate Normal Distribution Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applied Biostatistics Mean and Standard Deviation the Mean the Median Is Not the Only Measure of Central Value for a Distribution

Health Sciences M.Sc. Programme Applied Biostatistics Mean and Standard Deviation The mean The median is not the only measure of central value for a distribution. Another is the arithmetic mean or average, usually referred to simply as the mean. This is found by taking the sum of the observations and dividing by their number. The mean is often denoted by a little bar over the symbol for the variable, e.g. x . The sample mean has much nicer mathematical properties than the median and is thus more useful for the comparison methods described later. The median is a very useful descriptive statistic, but not much used for other purposes. Median, mean and skewness The sum of the 57 FEV1s is 231.51 and hence the mean is 231.51/57 = 4.06. This is very close to the median, 4.1, so the median is within 1% of the mean. This is not so for the triglyceride data. The median triglyceride is 0.46 but the mean is 0.51, which is higher. The median is 10% away from the mean. If the distribution is symmetrical the sample mean and median will be about the same, but in a skew distribution they will not. If the distribution is skew to the right, as for serum triglyceride, the mean will be greater, if it is skew to the left the median will be greater. This is because the values in the tails affect the mean but not the median. Figure 1 shows the positions of the mean and median on the histogram of triglyceride. -

1. How Different Is the T Distribution from the Normal?

Statistics 101–106 Lecture 7 (20 October 98) c David Pollard Page 1 Read M&M §7.1 and §7.2, ignoring starred parts. Reread M&M §3.2. The eects of estimated variances on normal approximations. t-distributions. Comparison of two means: pooling of estimates of variances, or paired observations. In Lecture 6, when discussing comparison of two Binomial proportions, I was content to estimate unknown variances when calculating statistics that were to be treated as approximately normally distributed. You might have worried about the effect of variability of the estimate. W. S. Gosset (“Student”) considered a similar problem in a very famous 1908 paper, where the role of Student’s t-distribution was first recognized. Gosset discovered that the effect of estimated variances could be described exactly in a simplified problem where n independent observations X1,...,Xn are taken from (, ) = ( + ...+ )/ a normal√ distribution, N . The sample mean, X X1 Xn n has a N(, / n) distribution. The random variable X Z = √ / n 2 2 Phas a standard normal distribution. If we estimate by the sample variance, s = ( )2/( ) i Xi X n 1 , then the resulting statistic, X T = √ s/ n no longer has a normal distribution. It has a t-distribution on n 1 degrees of freedom. Remark. I have written T , instead of the t used by M&M page 505. I find it causes confusion that t refers to both the name of the statistic and the name of its distribution. As you will soon see, the estimation of the variance has the effect of spreading out the distribution a little beyond what it would be if were used. -

Laws of Total Expectation and Total Variance

Laws of Total Expectation and Total Variance Definition of conditional density. Assume and arbitrary random variable X with density fX . Take an event A with P (A) > 0. Then the conditional density fXjA is defined as follows: 8 < f(x) 2 P (A) x A fXjA(x) = : 0 x2 = A Note that the support of fXjA is supported only in A. Definition of conditional expectation conditioned on an event. Z Z 1 E(h(X)jA) = h(x) fXjA(x) dx = h(x) fX (x) dx A P (A) A Example. For the random variable X with density function 8 < 1 3 64 x 0 < x < 4 f(x) = : 0 otherwise calculate E(X2 j X ≥ 1). Solution. Step 1. Z h i 4 1 1 1 x=4 255 P (X ≥ 1) = x3 dx = x4 = 1 64 256 4 x=1 256 Step 2. Z Z ( ) 1 256 4 1 E(X2 j X ≥ 1) = x2 f(x) dx = x2 x3 dx P (X ≥ 1) fx≥1g 255 1 64 Z ( ) ( )( ) h i 256 4 1 256 1 1 x=4 8192 = x5 dx = x6 = 255 1 64 255 64 6 x=1 765 Definition of conditional variance conditioned on an event. Var(XjA) = E(X2jA) − E(XjA)2 1 Example. For the previous example , calculate the conditional variance Var(XjX ≥ 1) Solution. We already calculated E(X2 j X ≥ 1). We only need to calculate E(X j X ≥ 1). Z Z Z ( ) 1 256 4 1 E(X j X ≥ 1) = x f(x) dx = x x3 dx P (X ≥ 1) fx≥1g 255 1 64 Z ( ) ( )( ) h i 256 4 1 256 1 1 x=4 4096 = x4 dx = x5 = 255 1 64 255 64 5 x=1 1275 Finally: ( ) 8192 4096 2 630784 Var(XjX ≥ 1) = E(X2jX ≥ 1) − E(XjX ≥ 1)2 = − = 765 1275 1625625 Definition of conditional expectation conditioned on a random variable. -

Multicollinearity

Chapter 10 Multicollinearity 10.1 The Nature of Multicollinearity 10.1.1 Extreme Collinearity The standard OLS assumption that ( xi1; xi2; : : : ; xik ) not be linearly related means that for any ( c1; c2; : : : ; ck ) xik =6 c1xi1 + c2xi2 + ··· + ck 1xi;k 1 (10.1) − − for some i. If the assumption is violated, then we can find ( c1; c2; : : : ; ck 1 ) such that − xik = c1xi1 + c2xi2 + ··· + ck 1xi;k 1 (10.2) − − for all i. Define x12 ··· x1k xk1 c1 x22 ··· x2k xk2 c2 X1 = 0 . 1 ; xk = 0 . 1 ; and c = 0 . 1 : . B C B C B C B xn2 ··· xnk C B xkn C B ck 1 C B C B C B − C @ A @ A @ A Then extreme collinearity can be represented as xk = X1c: (10.3) We have represented extreme collinearity in terms of the last explanatory vari- able. Since we can always re-order the variables this choice is without loss of generality and the analysis could be applied to any non-constant variable by moving it to the last column. 10.1.2 Near Extreme Collinearity Of course, it is rare, in practice, that an exact linear relationship holds. Instead, we have xik = c1xi1 + c2xi2 + ··· + ck 1xi;k 1 + vi (10.4) − − 133 134 CHAPTER 10. MULTICOLLINEARITY or, more compactly, xk = X1c + v; (10.5) where the v's are small relative to the x's. If we think of the v's as random variables they will have small variance (and zero mean if X includes a column of ones). A convenient way to algebraically express the degree of collinearity is the sample correlation between xik and wi = c1xi1 +c2xi2 +···+ck 1xi;k 1, namely − − cov( xik; wi ) cov( wi + vi; wi ) rx;w = = (10.6) var(xi;k)var(wi) var(wi + vi)var(wi) d d Clearly, as the variancep of vi grows small, thisp value will go to unity. -

Characteristics and Statistics of Digital Remote Sensing Imagery (1)

Characteristics and statistics of digital remote sensing imagery (1) Digital Images: 1 Digital Image • With raster data structure, each image is treated as an array of values of the pixels. • Image data is organized as rows and columns (or lines and pixels) start from the upper left corner of the image. • Each pixel (picture element) is treated as a separate unite. Statistics of Digital Images Help: • Look at the frequency of occurrence of individual brightness values in the image displayed • View individual pixel brightness values at specific locations or within a geographic area; • Compute univariate descriptive statistics to determine if there are unusual anomalies in the image data; and • Compute multivariate statistics to determine the amount of between-band correlation (e.g., to identify redundancy). 2 Statistics of Digital Images It is necessary to calculate fundamental univariate and multivariate statistics of the multispectral remote sensor data. This involves identification and calculation of – maximum and minimum value –the range, mean, standard deviation – between-band variance-covariance matrix – correlation matrix, and – frequencies of brightness values The results of the above can be used to produce histograms. Such statistics provide information necessary for processing and analyzing remote sensing data. A “population” is an infinite or finite set of elements. A “sample” is a subset of the elements taken from a population used to make inferences about certain characteristics of the population. (e.g., training signatures) 3 Large samples drawn randomly from natural populations usually produce a symmetrical frequency distribution. Most values are clustered around the central value, and the frequency of occurrence declines away from this central point. -

Linear Regression

eesc BC 3017 statistics notes 1 LINEAR REGRESSION Systematic var iation in the true value Up to now, wehav e been thinking about measurement as sampling of values from an ensemble of all possible outcomes in order to estimate the true value (which would, according to our previous discussion, be well approximated by the mean of a very large sample). Givenasample of outcomes, we have sometimes checked the hypothesis that it is a random sample from some ensemble of outcomes, by plotting the data points against some other variable, such as ordinal position. Under the hypothesis of random selection, no clear trend should appear.Howev er, the contrary case, where one finds a clear trend, is very important. Aclear trend can be a discovery,rather than a nuisance! Whether it is adiscovery or a nuisance (or both) depends on what one finds out about the reasons underlying the trend. In either case one must be prepared to deal with trends in analyzing data. Figure 2.1 (a) shows a plot of (hypothetical) data in which there is a very clear trend. The yaxis scales concentration of coliform bacteria sampled from rivers in various regions (units are colonies per liter). The x axis is a hypothetical indexofregional urbanization, ranging from 1 to 10. The hypothetical data consist of 6 different measurements at each levelofurbanization. The mean of each set of 6 measurements givesarough estimate of the true value for coliform bacteria concentration for rivers in a region with that urbanization level. The jagged dark line drawn on the graph connects these estimates of true value and makes the trend quite clear: more extensive urbanization is associated with higher true values of bacteria concentration. -

CONDITIONAL EXPECTATION Definition 1. Let (Ω,F,P)

CONDITIONAL EXPECTATION 1. CONDITIONAL EXPECTATION: L2 THEORY ¡ Definition 1. Let (,F ,P) be a probability space and let G be a σ algebra contained in F . For ¡ any real random variable X L2(,F ,P), define E(X G ) to be the orthogonal projection of X 2 j onto the closed subspace L2(,G ,P). This definition may seem a bit strange at first, as it seems not to have any connection with the naive definition of conditional probability that you may have learned in elementary prob- ability. However, there is a compelling rationale for Definition 1: the orthogonal projection E(X G ) minimizes the expected squared difference E(X Y )2 among all random variables Y j ¡ 2 L2(,G ,P), so in a sense it is the best predictor of X based on the information in G . It may be helpful to consider the special case where the σ algebra G is generated by a single random ¡ variable Y , i.e., G σ(Y ). In this case, every G measurable random variable is a Borel function Æ ¡ of Y (exercise!), so E(X G ) is the unique Borel function h(Y ) (up to sets of probability zero) that j minimizes E(X h(Y ))2. The following exercise indicates that the special case where G σ(Y ) ¡ Æ for some real-valued random variable Y is in fact very general. Exercise 1. Show that if G is countably generated (that is, there is some countable collection of set B G such that G is the smallest σ algebra containing all of the sets B ) then there is a j 2 ¡ j G measurable real random variable Y such that G σ(Y ). -

Conditional Expectation and Prediction Conditional Frequency Functions and Pdfs Have Properties of Ordinary Frequency and Density Functions

Conditional expectation and prediction Conditional frequency functions and pdfs have properties of ordinary frequency and density functions. Hence, associated with a conditional distribution is a conditional mean. Y and X are discrete random variables, the conditional frequency function of Y given x is pY|X(y|x). Conditional expectation of Y given X=x is Continuous case: Conditional expectation of a function: Consider a Poisson process on [0, 1] with mean λ, and let N be the # of points in [0, 1]. For p < 1, let X be the number of points in [0, p]. Find the conditional distribution and conditional mean of X given N = n. Make a guess! Consider a Poisson process on [0, 1] with mean λ, and let N be the # of points in [0, 1]. For p < 1, let X be the number of points in [0, p]. Find the conditional distribution and conditional mean of X given N = n. We first find the joint distribution: P(X = x, N = n), which is the probability of x events in [0, p] and n−x events in [p, 1]. From the assumption of a Poisson process, the counts in the two intervals are independent Poisson random variables with parameters pλ and (1−p)λ (why?), so N has Poisson marginal distribution, so the conditional frequency function of X is Binomial distribution, Conditional expectation is np. Conditional expectation of Y given X=x is a function of X, and hence also a random variable, E(Y|X). In the last example, E(X|N=n)=np, and E(X|N)=Np is a function of N, a random variable that generally has an expectation Taken w.r.t. -

Negative Binomial Regression

STATISTICS COLUMN Negative Binomial Regression Shengping Yang PhD ,Gilbert Berdine MD In the hospital stay study discussed recently, it was mentioned that “in case overdispersion exists, Poisson regression model might not be appropriate.” I would like to know more about the appropriate modeling method in that case. Although Poisson regression modeling is wide- regression is commonly recommended. ly used in count data analysis, it does have a limita- tion, i.e., it assumes that the conditional distribution The Poisson distribution can be considered to of the outcome variable is Poisson, which requires be a special case of the negative binomial distribution. that the mean and variance be equal. The data are The negative binomial considers the results of a se- said to be overdispersed when the variance exceeds ries of trials that can be considered either a success the mean. Overdispersion is expected for contagious or failure. A parameter ψ is introduced to indicate the events where the first occurrence makes a second number of failures that stops the count. The negative occurrence more likely, though still random. Poisson binomial distribution is the discrete probability func- regression of overdispersed data leads to a deflated tion that there will be a given number of successes standard error and inflated test statistics. Overdisper- before ψ failures. The negative binomial distribution sion may also result when the success outcome is will converge to a Poisson distribution for large ψ. not rare. To handle such a situation, negative binomial 0 5 10 15 20 25 0 5 10 15 20 25 Figure 1. Comparison of Poisson and negative binomial distributions. -

Section 1: Regression Review

Section 1: Regression review Yotam Shem-Tov Fall 2015 Yotam Shem-Tov STAT 239A/ PS 236A September 3, 2015 1 / 58 Contact information Yotam Shem-Tov, PhD student in economics. E-mail: [email protected]. Office: Evans hall room 650 Office hours: To be announced - any preferences or constraints? Feel free to e-mail me. Yotam Shem-Tov STAT 239A/ PS 236A September 3, 2015 2 / 58 R resources - Prior knowledge in R is assumed In the link here is an excellent introduction to statistics in R . There is a free online course in coursera on programming in R. Here is a link to the course. An excellent book for implementing econometric models and method in R is Applied Econometrics with R. This is my favourite for starting to learn R for someone who has some background in statistic methods in the social science. The book Regression Models for Data Science in R has a nice online version. It covers the implementation of regression models using R . A great link to R resources and other cool programming and econometric tools is here. Yotam Shem-Tov STAT 239A/ PS 236A September 3, 2015 3 / 58 Outline There are two general approaches to regression 1 Regression as a model: a data generating process (DGP) 2 Regression as an algorithm (i.e., an estimator without assuming an underlying structural model). Overview of this slides: 1 The conditional expectation function - a motivation for using OLS. 2 OLS as the minimum mean squared error linear approximation (projections). 3 Regression as a structural model (i.e., assuming the conditional expectation is linear). -

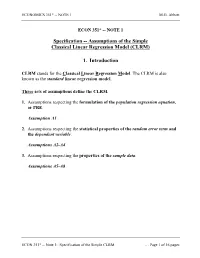

Assumptions of the Simple Classical Linear Regression Model (CLRM)

ECONOMICS 351* -- NOTE 1 M.G. Abbott ECON 351* -- NOTE 1 Specification -- Assumptions of the Simple Classical Linear Regression Model (CLRM) 1. Introduction CLRM stands for the Classical Linear Regression Model. The CLRM is also known as the standard linear regression model. Three sets of assumptions define the CLRM. 1. Assumptions respecting the formulation of the population regression equation, or PRE. Assumption A1 2. Assumptions respecting the statistical properties of the random error term and the dependent variable. Assumptions A2-A4 3. Assumptions respecting the properties of the sample data. Assumptions A5-A8 ECON 351* -- Note 1: Specification of the Simple CLRM … Page 1 of 16 pages ECONOMICS 351* -- NOTE 1 M.G. Abbott • Figure 2.1 Plot of Population Data Points, Conditional Means E(Y|X), and the Population Regression Function PRF Y Fitted values 200 $ PRF = 175 e, ur β0 + β1Xi t i nd 150 pe ex n o i t 125 p um 100 cons y ekl e W 75 50 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 260 Weekly income, $ Recall that the solid line in Figure 2.1 is the population regression function, which takes the form f (Xi ) = E(Yi Xi ) = β0 + β1Xi . For each population value Xi of X, there is a conditional distribution of population Y values and a corresponding conditional distribution of population random errors u, where (1) each population value of u for X = Xi is u i X i = Yi − E(Yi X i ) = Yi − β0 − β1 X i , and (2) each population value of Y for X = Xi is Yi X i = E(Yi X i ) + u i = β0 + β1 X i + u i . -

(Introduction to Probability at an Advanced Level) - All Lecture Notes

Fall 2018 Statistics 201A (Introduction to Probability at an advanced level) - All Lecture Notes Aditya Guntuboyina August 15, 2020 Contents 0.1 Sample spaces, Events, Probability.................................5 0.2 Conditional Probability and Independence.............................6 0.3 Random Variables..........................................7 1 Random Variables, Expectation and Variance8 1.1 Expectations of Random Variables.................................9 1.2 Variance................................................ 10 2 Independence of Random Variables 11 3 Common Distributions 11 3.1 Ber(p) Distribution......................................... 11 3.2 Bin(n; p) Distribution........................................ 11 3.3 Poisson Distribution......................................... 12 4 Covariance, Correlation and Regression 14 5 Correlation and Regression 16 6 Back to Common Distributions 16 6.1 Geometric Distribution........................................ 16 6.2 Negative Binomial Distribution................................... 17 7 Continuous Distributions 17 7.1 Normal or Gaussian Distribution.................................. 17 1 7.2 Uniform Distribution......................................... 18 7.3 The Exponential Density...................................... 18 7.4 The Gamma Density......................................... 18 8 Variable Transformations 19 9 Distribution Functions and the Quantile Transform 20 10 Joint Densities 22 11 Joint Densities under Transformations 23 11.1 Detour to Convolutions......................................