1. How Different Is the T Distribution from the Normal?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 22: Bivariate Normal Distribution Distribution

6.5 Conditional Distributions General Bivariate Normal Let Z1; Z2 ∼ N (0; 1), which we will use to build a general bivariate normal Lecture 22: Bivariate Normal Distribution distribution. 1 1 2 2 f (z1; z2) = exp − (z1 + z2 ) Statistics 104 2π 2 We want to transform these unit normal distributions to have the follow Colin Rundel arbitrary parameters: µX ; µY ; σX ; σY ; ρ April 11, 2012 X = σX Z1 + µX p 2 Y = σY [ρZ1 + 1 − ρ Z2] + µY Statistics 104 (Colin Rundel) Lecture 22 April 11, 2012 1 / 22 6.5 Conditional Distributions 6.5 Conditional Distributions General Bivariate Normal - Marginals General Bivariate Normal - Cov/Corr First, lets examine the marginal distributions of X and Y , Second, we can find Cov(X ; Y ) and ρ(X ; Y ) Cov(X ; Y ) = E [(X − E(X ))(Y − E(Y ))] X = σX Z1 + µX h p i = E (σ Z + µ − µ )(σ [ρZ + 1 − ρ2Z ] + µ − µ ) = σX N (0; 1) + µX X 1 X X Y 1 2 Y Y 2 h p 2 i = N (µX ; σX ) = E (σX Z1)(σY [ρZ1 + 1 − ρ Z2]) h 2 p 2 i = σX σY E ρZ1 + 1 − ρ Z1Z2 p 2 2 Y = σY [ρZ1 + 1 − ρ Z2] + µY = σX σY ρE[Z1 ] p 2 = σX σY ρ = σY [ρN (0; 1) + 1 − ρ N (0; 1)] + µY = σ [N (0; ρ2) + N (0; 1 − ρ2)] + µ Y Y Cov(X ; Y ) ρ(X ; Y ) = = ρ = σY N (0; 1) + µY σX σY 2 = N (µY ; σY ) Statistics 104 (Colin Rundel) Lecture 22 April 11, 2012 2 / 22 Statistics 104 (Colin Rundel) Lecture 22 April 11, 2012 3 / 22 6.5 Conditional Distributions 6.5 Conditional Distributions General Bivariate Normal - RNG Multivariate Change of Variables Consequently, if we want to generate a Bivariate Normal random variable Let X1;:::; Xn have a continuous joint distribution with pdf f defined of S. -

Applied Biostatistics Mean and Standard Deviation the Mean the Median Is Not the Only Measure of Central Value for a Distribution

Health Sciences M.Sc. Programme Applied Biostatistics Mean and Standard Deviation The mean The median is not the only measure of central value for a distribution. Another is the arithmetic mean or average, usually referred to simply as the mean. This is found by taking the sum of the observations and dividing by their number. The mean is often denoted by a little bar over the symbol for the variable, e.g. x . The sample mean has much nicer mathematical properties than the median and is thus more useful for the comparison methods described later. The median is a very useful descriptive statistic, but not much used for other purposes. Median, mean and skewness The sum of the 57 FEV1s is 231.51 and hence the mean is 231.51/57 = 4.06. This is very close to the median, 4.1, so the median is within 1% of the mean. This is not so for the triglyceride data. The median triglyceride is 0.46 but the mean is 0.51, which is higher. The median is 10% away from the mean. If the distribution is symmetrical the sample mean and median will be about the same, but in a skew distribution they will not. If the distribution is skew to the right, as for serum triglyceride, the mean will be greater, if it is skew to the left the median will be greater. This is because the values in the tails affect the mean but not the median. Figure 1 shows the positions of the mean and median on the histogram of triglyceride. -

1 One Parameter Exponential Families

1 One parameter exponential families The world of exponential families bridges the gap between the Gaussian family and general dis- tributions. Many properties of Gaussians carry through to exponential families in a fairly precise sense. • In the Gaussian world, there exact small sample distributional results (i.e. t, F , χ2). • In the exponential family world, there are approximate distributional results (i.e. deviance tests). • In the general setting, we can only appeal to asymptotics. A one-parameter exponential family, F is a one-parameter family of distributions of the form Pη(dx) = exp (η · t(x) − Λ(η)) P0(dx) for some probability measure P0. The parameter η is called the natural or canonical parameter and the function Λ is called the cumulant generating function, and is simply the normalization needed to make dPη fη(x) = (x) = exp (η · t(x) − Λ(η)) dP0 a proper probability density. The random variable t(X) is the sufficient statistic of the exponential family. Note that P0 does not have to be a distribution on R, but these are of course the simplest examples. 1.0.1 A first example: Gaussian with linear sufficient statistic Consider the standard normal distribution Z e−z2=2 P0(A) = p dz A 2π and let t(x) = x. Then, the exponential family is eη·x−x2=2 Pη(dx) / p 2π and we see that Λ(η) = η2=2: eta= np.linspace(-2,2,101) CGF= eta**2/2. plt.plot(eta, CGF) A= plt.gca() A.set_xlabel(r'$\eta$', size=20) A.set_ylabel(r'$\Lambda(\eta)$', size=20) f= plt.gcf() 1 Thus, the exponential family in this setting is the collection F = fN(η; 1) : η 2 Rg : d 1.0.2 Normal with quadratic sufficient statistic on R d As a second example, take P0 = N(0;Id×d), i.e. -

On the Meaning and Use of Kurtosis

Psychological Methods Copyright 1997 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1997, Vol. 2, No. 3,292-307 1082-989X/97/$3.00 On the Meaning and Use of Kurtosis Lawrence T. DeCarlo Fordham University For symmetric unimodal distributions, positive kurtosis indicates heavy tails and peakedness relative to the normal distribution, whereas negative kurtosis indicates light tails and flatness. Many textbooks, however, describe or illustrate kurtosis incompletely or incorrectly. In this article, kurtosis is illustrated with well-known distributions, and aspects of its interpretation and misinterpretation are discussed. The role of kurtosis in testing univariate and multivariate normality; as a measure of departures from normality; in issues of robustness, outliers, and bimodality; in generalized tests and estimators, as well as limitations of and alternatives to the kurtosis measure [32, are discussed. It is typically noted in introductory statistics standard deviation. The normal distribution has a kur- courses that distributions can be characterized in tosis of 3, and 132 - 3 is often used so that the refer- terms of central tendency, variability, and shape. With ence normal distribution has a kurtosis of zero (132 - respect to shape, virtually every textbook defines and 3 is sometimes denoted as Y2)- A sample counterpart illustrates skewness. On the other hand, another as- to 132 can be obtained by replacing the population pect of shape, which is kurtosis, is either not discussed moments with the sample moments, which gives or, worse yet, is often described or illustrated incor- rectly. Kurtosis is also frequently not reported in re- ~(X i -- S)4/n search articles, in spite of the fact that virtually every b2 (•(X i - ~')2/n)2' statistical package provides a measure of kurtosis. -

Characteristics and Statistics of Digital Remote Sensing Imagery (1)

Characteristics and statistics of digital remote sensing imagery (1) Digital Images: 1 Digital Image • With raster data structure, each image is treated as an array of values of the pixels. • Image data is organized as rows and columns (or lines and pixels) start from the upper left corner of the image. • Each pixel (picture element) is treated as a separate unite. Statistics of Digital Images Help: • Look at the frequency of occurrence of individual brightness values in the image displayed • View individual pixel brightness values at specific locations or within a geographic area; • Compute univariate descriptive statistics to determine if there are unusual anomalies in the image data; and • Compute multivariate statistics to determine the amount of between-band correlation (e.g., to identify redundancy). 2 Statistics of Digital Images It is necessary to calculate fundamental univariate and multivariate statistics of the multispectral remote sensor data. This involves identification and calculation of – maximum and minimum value –the range, mean, standard deviation – between-band variance-covariance matrix – correlation matrix, and – frequencies of brightness values The results of the above can be used to produce histograms. Such statistics provide information necessary for processing and analyzing remote sensing data. A “population” is an infinite or finite set of elements. A “sample” is a subset of the elements taken from a population used to make inferences about certain characteristics of the population. (e.g., training signatures) 3 Large samples drawn randomly from natural populations usually produce a symmetrical frequency distribution. Most values are clustered around the central value, and the frequency of occurrence declines away from this central point. -

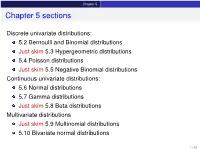

Chapter 5 Sections

Chapter 5 Chapter 5 sections Discrete univariate distributions: 5.2 Bernoulli and Binomial distributions Just skim 5.3 Hypergeometric distributions 5.4 Poisson distributions Just skim 5.5 Negative Binomial distributions Continuous univariate distributions: 5.6 Normal distributions 5.7 Gamma distributions Just skim 5.8 Beta distributions Multivariate distributions Just skim 5.9 Multinomial distributions 5.10 Bivariate normal distributions 1 / 43 Chapter 5 5.1 Introduction Families of distributions How: Parameter and Parameter space pf /pdf and cdf - new notation: f (xj parameters ) Mean, variance and the m.g.f. (t) Features, connections to other distributions, approximation Reasoning behind a distribution Why: Natural justification for certain experiments A model for the uncertainty in an experiment All models are wrong, but some are useful – George Box 2 / 43 Chapter 5 5.2 Bernoulli and Binomial distributions Bernoulli distributions Def: Bernoulli distributions – Bernoulli(p) A r.v. X has the Bernoulli distribution with parameter p if P(X = 1) = p and P(X = 0) = 1 − p. The pf of X is px (1 − p)1−x for x = 0; 1 f (xjp) = 0 otherwise Parameter space: p 2 [0; 1] In an experiment with only two possible outcomes, “success” and “failure”, let X = number successes. Then X ∼ Bernoulli(p) where p is the probability of success. E(X) = p, Var(X) = p(1 − p) and (t) = E(etX ) = pet + (1 − p) 8 < 0 for x < 0 The cdf is F(xjp) = 1 − p for 0 ≤ x < 1 : 1 for x ≥ 1 3 / 43 Chapter 5 5.2 Bernoulli and Binomial distributions Binomial distributions Def: Binomial distributions – Binomial(n; p) A r.v. -

Basic Econometrics / Statistics Statistical Distributions: Normal, T, Chi-Sq, & F

Basic Econometrics / Statistics Statistical Distributions: Normal, T, Chi-Sq, & F Course : Basic Econometrics : HC43 / Statistics B.A. Hons Economics, Semester IV/ Semester III Delhi University Course Instructor: Siddharth Rathore Assistant Professor Economics Department, Gargi College Siddharth Rathore guj75845_appC.qxd 4/16/09 12:41 PM Page 461 APPENDIX C SOME IMPORTANT PROBABILITY DISTRIBUTIONS In Appendix B we noted that a random variable (r.v.) can be described by a few characteristics, or moments, of its probability function (PDF or PMF), such as the expected value and variance. This, however, presumes that we know the PDF of that r.v., which is a tall order since there are all kinds of random variables. In practice, however, some random variables occur so frequently that statisticians have determined their PDFs and documented their properties. For our purpose, we will consider only those PDFs that are of direct interest to us. But keep in mind that there are several other PDFs that statisticians have studied which can be found in any standard statistics textbook. In this appendix we will discuss the following four probability distributions: 1. The normal distribution 2. The t distribution 3. The chi-square (2 ) distribution 4. The F distribution These probability distributions are important in their own right, but for our purposes they are especially important because they help us to find out the probability distributions of estimators (or statistics), such as the sample mean and sample variance. Recall that estimators are random variables. Equipped with that knowledge, we will be able to draw inferences about their true population values. -

Linear Regression

eesc BC 3017 statistics notes 1 LINEAR REGRESSION Systematic var iation in the true value Up to now, wehav e been thinking about measurement as sampling of values from an ensemble of all possible outcomes in order to estimate the true value (which would, according to our previous discussion, be well approximated by the mean of a very large sample). Givenasample of outcomes, we have sometimes checked the hypothesis that it is a random sample from some ensemble of outcomes, by plotting the data points against some other variable, such as ordinal position. Under the hypothesis of random selection, no clear trend should appear.Howev er, the contrary case, where one finds a clear trend, is very important. Aclear trend can be a discovery,rather than a nuisance! Whether it is adiscovery or a nuisance (or both) depends on what one finds out about the reasons underlying the trend. In either case one must be prepared to deal with trends in analyzing data. Figure 2.1 (a) shows a plot of (hypothetical) data in which there is a very clear trend. The yaxis scales concentration of coliform bacteria sampled from rivers in various regions (units are colonies per liter). The x axis is a hypothetical indexofregional urbanization, ranging from 1 to 10. The hypothetical data consist of 6 different measurements at each levelofurbanization. The mean of each set of 6 measurements givesarough estimate of the true value for coliform bacteria concentration for rivers in a region with that urbanization level. The jagged dark line drawn on the graph connects these estimates of true value and makes the trend quite clear: more extensive urbanization is associated with higher true values of bacteria concentration. -

The Normal Moment Generating Function

MSc. Econ: MATHEMATICAL STATISTICS, 1996 The Moment Generating Function of the Normal Distribution Recall that the probability density function of a normally distributed random variable x with a mean of E(x)=and a variance of V (x)=2 is 2 1 1 (x)2/2 (1) N(x; , )=p e 2 . (22) Our object is to nd the moment generating function which corresponds to this distribution. To begin, let us consider the case where = 0 and 2 =1. Then we have a standard normal, denoted by N(z;0,1), and the corresponding moment generating function is dened by Z zt zt 1 1 z2 Mz(t)=E(e )= e √ e 2 dz (2) 2 1 t2 = e 2 . To demonstate this result, the exponential terms may be gathered and rear- ranged to give exp zt exp 1 z2 = exp 1 z2 + zt (3) 2 2 1 2 1 2 = exp 2 (z t) exp 2 t . Then Z 1t2 1 1(zt)2 Mz(t)=e2 √ e 2 dz (4) 2 1 t2 = e 2 , where the nal equality follows from the fact that the expression under the integral is the N(z; = t, 2 = 1) probability density function which integrates to unity. Now consider the moment generating function of the Normal N(x; , 2) distribution when and 2 have arbitrary values. This is given by Z xt xt 1 1 (x)2/2 (5) Mx(t)=E(e )= e p e 2 dx (22) Dene x (6) z = , which implies x = z + . 1 MSc. Econ: MATHEMATICAL STATISTICS: BRIEF NOTES, 1996 Then, using the change-of-variable technique, we get Z 1 1 2 dx t zt p 2 z Mx(t)=e e e dz 2 dz Z (2 ) (7) t zt 1 1 z2 = e e √ e 2 dz 2 t 1 2t2 = e e 2 , Here, to establish the rst equality, we have used dx/dz = . -

A Family of Skew-Normal Distributions for Modeling Proportions and Rates with Zeros/Ones Excess

S S symmetry Article A Family of Skew-Normal Distributions for Modeling Proportions and Rates with Zeros/Ones Excess Guillermo Martínez-Flórez 1, Víctor Leiva 2,* , Emilio Gómez-Déniz 3 and Carolina Marchant 4 1 Departamento de Matemáticas y Estadística, Facultad de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad de Córdoba, Montería 14014, Colombia; [email protected] 2 Escuela de Ingeniería Industrial, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, 2362807 Valparaíso, Chile 3 Facultad de Economía, Empresa y Turismo, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and TIDES Institute, 35001 Canarias, Spain; [email protected] 4 Facultad de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad Católica del Maule, 3466706 Talca, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 19 August 2020; Published: 1 September 2020 Abstract: In this paper, we consider skew-normal distributions for constructing new a distribution which allows us to model proportions and rates with zero/one inflation as an alternative to the inflated beta distributions. The new distribution is a mixture between a Bernoulli distribution for explaining the zero/one excess and a censored skew-normal distribution for the continuous variable. The maximum likelihood method is used for parameter estimation. Observed and expected Fisher information matrices are derived to conduct likelihood-based inference in this new type skew-normal distribution. Given the flexibility of the new distributions, we are able to show, in real data scenarios, the good performance of our proposal. Keywords: beta distribution; centered skew-normal distribution; maximum-likelihood methods; Monte Carlo simulations; proportions; R software; rates; zero/one inflated data 1. -

Lecture 2 — September 24 2.1 Recap 2.2 Exponential Families

STATS 300A: Theory of Statistics Fall 2015 Lecture 2 | September 24 Lecturer: Lester Mackey Scribe: Stephen Bates and Andy Tsao 2.1 Recap Last time, we set out on a quest to develop optimal inference procedures and, along the way, encountered an important pair of assertions: not all data is relevant, and irrelevant data can only increase risk and hence impair performance. This led us to introduce a notion of lossless data compression (sufficiency): T is sufficient for P with X ∼ Pθ 2 P if X j T (X) is independent of θ. How far can we take this idea? At what point does compression impair performance? These are questions of optimal data reduction. While we will develop general answers to these questions in this lecture and the next, we can often say much more in the context of specific modeling choices. With this in mind, let's consider an especially important class of models known as the exponential family models. 2.2 Exponential Families Definition 1. The model fPθ : θ 2 Ωg forms an s-dimensional exponential family if each Pθ has density of the form: s ! X p(x; θ) = exp ηi(θ)Ti(x) − B(θ) h(x) i=1 • ηi(θ) 2 R are called the natural parameters. • Ti(x) 2 R are its sufficient statistics, which follows from NFFC. • B(θ) is the log-partition function because it is the logarithm of a normalization factor: s ! ! Z X B(θ) = log exp ηi(θ)Ti(x) h(x)dµ(x) 2 R i=1 • h(x) 2 R: base measure. -

Volatility Modeling Using the Student's T Distribution

Volatility Modeling Using the Student’s t Distribution Maria S. Heracleous Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics Aris Spanos, Chair Richard Ashley Raman Kumar Anya McGuirk Dennis Yang August 29, 2003 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Student’s t Distribution, Multivariate GARCH, VAR, Exchange Rates Copyright 2003, Maria S. Heracleous Volatility Modeling Using the Student’s t Distribution Maria S. Heracleous (ABSTRACT) Over the last twenty years or so the Dynamic Volatility literature has produced a wealth of uni- variateandmultivariateGARCHtypemodels.Whiletheunivariatemodelshavebeenrelatively successful in empirical studies, they suffer from a number of weaknesses, such as unverifiable param- eter restrictions, existence of moment conditions and the retention of Normality. These problems are naturally more acute in the multivariate GARCH type models, which in addition have the problem of overparameterization. This dissertation uses the Student’s t distribution and follows the Probabilistic Reduction (PR) methodology to modify and extend the univariate and multivariate volatility models viewed as alternative to the GARCH models. Its most important advantage is that it gives rise to internally consistent statistical models that do not require ad hoc parameter restrictions unlike the GARCH formulations. Chapters 1 and 2 provide an overview of my dissertation and recent developments in the volatil- ity literature. In Chapter 3 we provide an empirical illustration of the PR approach for modeling univariate volatility. Estimation results suggest that the Student’s t AR model is a parsimonious and statistically adequate representation of exchange rate returns and Dow Jones returns data.