Legislative Relief for War Injuries in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

8904 SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 31St DECEMBER 1960

8904 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 31sT DECEMBER 1960 Most Excellent Order of the British Empire George Travis HARGREAVES, Esq., Intelligence (contd.) Officer, Grade I, British Services Security Ordinary Members of the Civil Division (contd.) Organisation, Germany. Joseph HARPER, Esq., Senior Executive Officer, Robin John GARLAND, Esq., Clerk to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Hamibledon Rural District Council, Surrey. George Albert HARRIS, Esq., M.V.O., Chief William Joseph GARRATT, Esq., J.P. For public Clerk, Central Chancery of the Orders of services in Staffordshire. Knighthood. Charles Joseph GAYTON, Esq., Higher Executive Henry HARTFORD, Esq., Higher Executive Officer, Officer, War Damage Commission. National Assistance Board. Miss Jean Wallace GEDDES, Head Teacher, Donald William HARVEY, Esq. For political ser- Phoenix Park Nursery School, Glasgow. vices in Cirencester and Tewkesbury. Gerard Henry GEILERN, Esq., Senior Warning George Thomas HARVEY, Esq., J.P., Chairman, Officer, York, United Kingdom Warning Aberdare Local Savings Committee. • Organisation. Harry Albert HASKELL, Esq., Chairman, Guild- Jean Margaret, Mrs. GENESE, Assistant Secretary ford and District War Pensions Committee. Royal Forestry Society of England and Wales. Edgar Warmiington HAWKEN, Esq., Senior Execu- The Reverend Spencer Walter GERHOLD, Rector, tive Officer, Air Ministry. S. Pierre Du Bois, Guernsey, Channel Islands. Percy James HAYDEN, Esq., lately Assistant For public services in Guernsey. Official Receiver, Board of Trade. John McDonald Frame GIBSON, Esq., Chairman, Godfrey HAYNES, Esq., Works Manager, Tyer East Renfrewshire Savings Committee. and Company, Ltd., Guildford. Thomas Arthur GIBSON, Esq., Clerk and Chief Harry HEAD, Esq., Trawler Skipper, Lowestoft. Fishery Officer, South Wales Sea Fisheries James Gerald HEAPS, Esq., Chief of Test and District Committee. -

BOARD of DEPUTIES of BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1944.Pdf

THE LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (iFOUNDED IN 1760) GENERALLY KNOWN AS THE BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1944 WOBURN HOUSE UPPER WOBURN PLACE LONDON, W.C.I 1945 .4-2. fd*׳American Jewish Comm LiBKARY FORM OF BEQUEST I bequeath to the LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (generally known as the Board of Deputies of British Jews) the sum of £ free of duty, to be applied to the general purposes of the said Board and the receipt of the Treasurer for the time being of the said Board shall be a sufficient discharge for the same. Contents List of Officers of the Board .. .. 2 List of Former Presidents .. .. .. 3 List of Congregations and Institutions represented on the Board .. .... .. 4 Committees .. .. .. .. .. ..10 Annual Report—Introduction .. .. 13 Administrative . .. .. 14 Executive Committee .. .. .. ..15 Aliens Committee .. .. .. .. 18 Education Committee . .. .. 20 Finance Committee . .. 21 Jewish Defence Committee . .. 21 Law, Parliamentary and General Purposes Committee . 24 Palestine Committee .. .. .. 28 Foreign Affairs Committee . .. .. ... 30 Accounts 42 C . 4 a פ) 3 ' P, . (OffuiTS 01 tt!t iBaarft President: PROFESSOR S. BRODETSKY Vice-Presidents : DR. ISRAEL FELDMAN PROFESSOR SAMSON WRIGHT Treasurer : M. GORDON LIVERMAN, J,P. Hon. Auditors : JOSEPH MELLER, O.B.E. THE RT. HON. LORD SWAYTHLING Solicitor : CHARLES H. L. EMANUEL, M.A. Auditors : MESSRS. JOHN DIAMOND & Co. Secretary : A. G. BROTMAN, B.SC. All communications should be addressed to THE SECRETARY at:— Woburn House, Upper Woburn Place, London, W.C.I Telephone : EUSton 3952-3 Telegraphic Address : Deputies, Kincross, London Cables : Deputies, London 2 Past $xmbmt% 0f tht Uoati 1760 BENJAMIN MENDES DA COSTA 1766 JOSEPH SALVADOR 1778 JOSEPH SALVADOR 1789 MOSES ISAAC LEVY 1800-1812 . -

Ariège's Development Conundrum

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 4-30-2014 Ariège’s Development Conundrum Alan Thomas Devenish Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Growth and Development Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Devenish, Alan Thomas, "Ariège’s Development Conundrum" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1787. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1786 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Ariège’s Development Conundrum by Alan Thomas Devenish A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geography Thesis Committee: Barbara Brower, Chair David Banis Daniel Johnson Portland State University 2014 © 2014 Alan Thomas Devenish i Abstract Since the latter half of the nineteenth century, industrialization and modernization have strongly shaped the development of the French department Ariège. Over the last roughly 150 years, Ariège has seen its population decline from a quarter million to 150,00. Its traditional agrarian economy has been remade for competition on global markets, and the department has relied on tourism to bring in revenue where other traditional industries have failed to do so. In this thesis I identify the European Union and French policies that continue to guide Ariège’s development through subsidies and regulation. -

Records Relating to the 1939 – 1945 War

Records Relating to the 1939 – 1945 War This is a list of resources in the three branches of the Record Office which relate exclusively to the 1939-1945 War and which were created because of the War. However, virtually every type of organisation was affected in some way by the War so it could also be worthwhile looking at the minute books and correspondence files of local councils, churches, societies and organisations, and also school logbooks. The list is in three sections: Pages 1-10: references in all the archive collections except for the Suffolk Regiment archive. They are arranged by theme, moving broadly from the beginning of the War to its end. Pages 10-12: printed books in the Local Studies collections. Pages 12-21: references in the Suffolk Regiment archive (held in the Bury St Edmunds branch). These are mainly arranged by Battalion. (B) = Bury Record Office; (I) = Ipswich Record Office; (L) = Lowestoft Record Office 1. Air Raid Precautions and air raids ADB506/3 Letter re air-raid procedure, 1940 (B) D12/4/1-2 Bury Borough ARP Control Centre, in and out messages, 1940-1945 (B) ED500/E1/14 Hadleigh Police Station ARP file, 1943-1944 (B) EE500/1/125 Bury Borough ARP Committee minutes, 1935-1939 (B) EE500/33/17/1-7 Bury Town Clerk’s files, 1937-1950 (B) EE500/33/18/1-6 Bury Town Clerk’s files re Fire Guard, 1938-1947 (B) EE500/44/155-6 Bury Borough: cash books re Government Shelter scheme (B) EE501/6/142-147 Sudbury Borough ARP registers, report books and papers, 1938-1945 (B) EE501/8/27(323, Plans of air-raid shelters, Sudbury, -

NZHC 3138 BETWEEN EARTHQUAKE COMMISSION Plaintiff

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND WELLINGTON REGISTRY CIV 2014-485-5698 [2014] NZHC 3138 BETWEEN EARTHQUAKE COMMISSION Plaintiff AND INSURANCE COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND INCORPORATED First Defendant CHRISTCHURCH CITY COUNCIL Second Defendant SOUTHERN RESPONSE EARTHQUAKE SERVICES LTD Third Defendant Hearing: 28, 29, 30 and 31 October 2014 (at Christchurch) Court: Heath, Kós and Gilbert JJ Counsel: J E Hodder QC, B A Scott, T D Smith and G K Rippingale for Plaintiff D J Goddard QC, J D Every-Palmer and S K Swinerd for First Defendant D A Ward for Second Defendant D J Friar and M Powell for Third Defendant D A Webb and S Goodwin for Flockton Cluster Group (Intervener) G D R Shand and J A Glucina for Ms D Culf (Intervener) T C Weston QC and K L Clark QC, amici curiae Judgment: 10 December 2014 JUDGMENT OF THE COURT This judgment was delivered by me on 10 December 2014 at 9.30am pursuant to Rule 11.5 of the High Court Rules Registrar/Deputy Registrar EARTHQUAKE COMMISSION v INSURANCE COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND INCORPORATED [2014] NZHC 3138 [10 December 2014] CONTENTS PART 1: INTRODUCTION The proceeding [1] The scheme of the Earthquake Commission Act 1993 [11] Agreed facts (a) The Canterbury earthquakes [22] (b) The relevant land [27] (c) Land classification in Christchurch since the earthquakes [31] (d) Flooding Vulnerability [35] The Commission’s Increased Flooding Vulnerability Policy (a) Development of the Policy [39] (b) The Policy in outline [45] (c) Assessment of Increased Flooding Vulnerability [46] (d) Settlement of Increased Flooding Vulnerability -

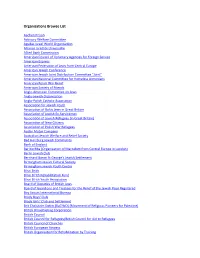

Organisations Browse List

Organisations Browse List Aachen Prison Advisory Welfare Committee Agudas Israel World Organisation Alliance Israélite Universelle Allied Bank Commission American Council of Voluntary Agencies for Foreign Service American Express American Federation of Jews from Central Europe American Jewish Conference American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee "Joint" American National Committee for Homeless Armenians American Polish War Relief American Society of Friends Anglo-American Committee on Jews Anglo-Jewish Organisation Anglo-Polish Catholic Association Association for Jewish Youth Association of Baltic Jews in Great Britain Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen Association of Jewish Refugees (in Great Britain) Association of New Citizens Association of Polish War Refugees Austin Motor Company Australian Jewish Welfare and Relief Society Bad Harzburg Jewish Community Bank of England Bar Kochba (Organisation of Maccabim from Central Europe in London) Berlin Jewish Club Bernhard Baron St George's Jewish Settlement Birmingham Jewish Cultural Society Birmingham Jewish Youth Centre B'nai Brith B'nai B'rith Rehabilitation Fund B'nai B'rith Youth Association Board of Deputies of British Jews Board of Guardians and Trustees for the Relief of the Jewish Poor Registered Boy Scouts International Bureau Brady Boys' Club Brady Girls' Club and Settlement Brit Chalutzim Datim (BaCHaD) (Movement of Religious Pioneers for Palestine) British Broadcasting Corporation British Council British Council for Refugees/British Council for Aid to Refugees British Council -

Harry Colmery Collection, 1911-1979

Overview of the Collection Repository Kansas State Historical Society Creator Harry W. Colmery Title The Harry W. Colmery Collection Dates c.a. 1911 – c.a. 1979 (bulk c.a. 1925 – c.a. 1965) Quantity 266 cu. ft. Abstract Harry Walter Colmery: lawyer, insurance agent, politician, legionnaire; of Topeka, Kan., Washington, D.C. Legal case files of Harry Colmery from more than five decades of practicing law, includes legal documents and correspondence with clients; insurance materials from Pioneer National Life Insurance Company of Topeka, insurance books and journals, and other material regarding Colmery’s work on the boards of insurance companies; political material from Colmery’s Senatorial run in 1950, work with the Republican Party, and work on campaigns for other Republican candidates, including John Hamilton, Wendell Willkie, and Barry Goldwater; materials concerning Colmery’s civic involvement in organizations like the Kiwanis Club, Topeka Chamber of Commerce, YMCA, YWCA, and Boy Scouts of America; material from Colmery’s service as Civilian Aide to the Secretary of the War for Kansas; material from Colmery’s involvement with Colonel Andres Soriano of the Philippines, including legal material, information on Soriano’s businesses, and other material regarding the Philippines; personal information relating to Colmery, including correspondence, scrapbooks, newspaper clippings, autobiographical sketches, and yearbooks; financial information, both personal and business, including records, receipts, bookkeeping, etc.; materials from Colmery’s involvement with the American Legion, including his service as National Commander, information on the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (the G.I. Bill of Rights), and work with the Kansas Department of the American Legion and Capitol Post No. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 1 January, 1951

20 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 1 JANUARY, 1951 William Ernest SPENCE, Esq., District Delegate, William Rueben WATSON, Esq., Assistant to Amalgamated .Society of Woodworkers, the .Commercial Superintendent, Eastern . Humber District. " ' - Region, Railway Executive. Algernon William STEVENS, Esq., Senior Miss Agnes Baillie WHITE, Executive Officer, . Executive Officer, Ministry of Transport. Allied Commission for Austria, British William STEVENS, Esq., Member 'of the . Element. ,- National Executive Council of the National Francis Henry WHITEHEAD, Esq., MrR.CS., Union of Public Employees. L.R.C.P., Chairman, Wandsworth and Robert STEWART, Esq., Staff Officer, Ministry Battersea War Pensions Committee. of Labour and National Insurance, Northern Miss Doris Lizzie Mary WHITEMAN, Higher Ireland. Executive Officer, War Damage Commission Alban Maurice STICKLAN, Esq., Warden, Wel- . and Central Land Board. fare Department of the London County John WHITESIDE, Esq., Vice-President, Bridling- 1 ' Council. ton and District Savings Committee. Reginald Henry STONE, Esq., lately Higher Dalby Walter Harry WICKSON, Esq., Passport Clerical Officer, Ministry of Supply. Officer in the Office of the United Kingdom Miss Marjorie Anne STOTESBURY, Higher High Commissioner, Cape Town. Executive Officer, Board of Trade. Benjamin Richard WILLIAMS, Esq., Higher William Alexander STUART, Esq., lately Higher • Executive Officer, National Assistance Executive Officer, Board of Trade. Board. Miss Dorothy STUTFIELD, Superintendent of Thomas Charles Richard WILLIS, Esq., Typists, Air Ministry. Assistant Regional Manager, London (South Captain Frederick SUMMERS, Master, s.s. Western) Region, War Damage Commission "Brika", F.C. Strick and Company. and Central Land Board. James John SYMONS, Esq., Chief Male Nurse, Miss .Winifred WILSON, Higher Clerical Officer, Warlingham Park Hospital, Surrey. Telephone Manager's Office, Middlesbrough, James TALBOT, Esq., Senior Executive Officer, Yorkshire. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 4 January, 1943

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 4 JANUARY, 1943 Desmond MacMahon, Esq., Mus.Doc., Fire Alfred German Rose, Esq., Governing Director Prevention Officer, Corporation of Birming- of Rose Bros., Ltd., and of the -Northern ham. For services to Civil Defence. Manufacturing Company, Ltd. Captain Robert Peter Mann (Lieutenant-Com- Arthur Poisue Kowe, Esq., Public Relations mander, R.A.N.R. (Ret'd.)), Master, Mer- Officer, War Damage Commission. chant Navy. Commodore of Fleet, Bibby Howard Percival Rowe, Esq., Cmef Engineer Line. Officer, Merchant Navy. George Ernest Martin, Esq., Borough Treasurer Albert Edgar Rowsell, Esq., M.M., Chief and Accountant, Poplar. Constable, City of Exeter. For services to Reginald Henry Mathews, Esq., Senior Meteor- Civil Defence. ological Officer, Bomber Command, Royal James Thomas Ruck, Esq., Regional Works Air Force. Adviser and Co-ordinating Officer, North Thomas Meehan, Esq., J.P., Divisional Officer, Midland Region, Ministry of Home Security. Middlesbrough, Iron and Steel Trades Con- Captain Denis Frank Satchwell (Flying Officer, federation. R.A.F.O.), British Overseas Airways Cor- Robert Milligan, Esq., Chief Engineer Officer, poration. Merchant Navy. Elaine, Mrs. Scott, Officer in Charge of the Captain William Milne, Master, Merchant Navy. Evacuation Department for Children under Captain Thomas Frederick Milner, R.D. five, Women's Voluntary Services for Civil (Lieutenant-Commander, R.N.R. (Ret'd.)), Defence. Master, Merchant Navy. Andrew Shearer, Esq., Town Clerk of Dun- Bertie Minto, Esq., Chief Engineer Officer, fermline. Merchant Navy. Captain Eric Cameron Shore, Master, Mer- Barclay Brown Murdoch, Esq., A.I.C., Assist- chant Navy. ant Director of Materials Production, Minis- Councillor Herbert Edwin Simpkins, J.P., try of Aircraft Production. -

Federal Home Loan Bank Review

Vol.7 pfe No. 8 FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK REVIEW MAY 1941 ISSUED BY FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK BOARD WASHINGTON D.C. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis CONTENTS FOR MAY 1941 ARTICLES Page FEDERAL BUSINESS PROMOTION EXPENDITURES OF SAVINGS AND LOAN ASSOCIATIONS 242 Substantial increase in participating associations—Size of business promotion expenditures—Distribution of the advertising dollar— The effect of size on advertising programs—The cost of obtaining HOME new business. PROPERTY INSURANCE AGAINST WAR RISKS 248 History of the British War Damage Bill—-Is war damage an insur able risk?—-Framework of the Bill—Contributions: the mortgagee's LOAN share—-Basis of compensation—Administration of the Bill. SHARE CAPITAL TURNOVER 251 Principal results of capital turnover study—Use of turnover data— Variations by asset and by community size groups—Repurchases compared with new investments—Repurchase ratios by asset and and by community size groups—Geographic variations—Further BANK studies needed. LIFE INSURANCE COMPANIES: THEIR INVESTMENT POLICIES DURING 1940 257 The 1940 investment program—The problem of investment out REVIEW lets—'The accumulation of savings in life insurance companies. THE ROOFS OVER AMERICAN HOMES 260 Questionnaire survey of roofing practices in the U. S.--Two regional surveys—Weathering qualities of roofing materials. Published Monthly by the FEDERAL HOME LOAN MONTHLY SURVEY BANK BOARD Highlights and summary 267 General business conditions 268 Foreclosures 268 John H. Fahey, Chairman Residential construction 268 T. D. Webb, Vice Chairman Building costs 269 F. W. Catlett W. H. Husband New mortgage-lending activity of savings and loan associations 269 F. -

Burial Board Minutes 1939-1951

Northwood Cemetery Burial Board Minute Book (1939-1951) Quarterly meeting of the Burial Committee, 25th July 1939 at 7:00pm Present Councillor F W B Baskett (Chairman) Councillor Captain J H Dibley, MC Councillor G H Hummel Apologies for non-attendance were received from the Chairman of the Council and Councillor Mason. Minutes The Minutes of the Quarterly Meeting of the Committee held on 25th April 1939 (a copy of which had been supplied to each Member) were read and confirmed. Curators’ Reports The Curators made their reports. Proposed by Councillor Hummel, seconded by Councillor Captain Dibley and resolved that the application of one of the men employed at Northwood Cemetery to be paid extra for working when necessary on Saturday afternoons (instead of being allowed time off in lieu of the time worked on Saturday afternoons) be not entertained. With regard to the application of the Curator, Northwood Cemetery have another man at the Northwood Cemetery in place of the man who was away sick, and on account of the fact that one man would soon be called up for service in the Territorial Army, it was proposed by Councillor Captain Dibley, seconded by Councillor Hummel and resolved that the matter be left in the hands of the Chairman of the Committee and the Surveyor to make the best possible arrangements. A letter (dated the 23rd instant) from the Curator of the East Cowes Cemetery apologising for his inability to be present at the meeting because he was away on annual holiday, and stating that W Clayden was acting as Curator during his absence, was read.