St Marylebone and the Portman Estate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buses from Knightsbridge

Buses from Knightsbridge 23 414 24 Buses towardsfrom Westbourne Park BusKnightsbridge Garage towards Maida Hill towards Hampstead Heath Shirland Road/Chippenham Road from stops KH, KP From 15 June 2019 route 14 will be re-routed to run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Warren towards Warren Street please change at Charing Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampstead Heath. 14 towards Willesden Bus Garage for Little Venice from stop KB, KD, KW 24 from stops KE, KF Maida Vale 23 414 Clifton Gardens Russell 24 Square Goodge towards Westbourne Park Bus Garage towards Maida Hill 74 towards Hampstead HeathStreet 19 452 Shirland Road/Chippenham Road towards fromtowards stops Kensal KH, KPRise 414From 15 June 2019 route 14from will be stops re-routed KB, KD to, KW run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Finsbury Park 22 TottenhamWarren Ladbroke Grove from stops KE, KF, KJ, KM towards Warren Street please change atBaker Charing Street Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampsteadfor Madame Heath. Tussauds from 14 stops KJ, KM Court from stops for Little Venice Road towards Willesden Bus Garage fromRegent stop Street KB, KD, KW KJ, KM Maida Vale 14 24 from stops KE, KF Edgware Road MargaretRussell Street/ Square Goodge 19 23 52 452 Clifton Gardens Oxford Circus Westbourne Bishop’s 74 Street Tottenham 19 Portobello and 452 Grove Bridge Road Paddington Oxford British Court Roadtowards Golborne Market towards Kensal Rise 414 fromGloucester stops KB, KD Place, KW Circus Museum Finsbury Park Ladbroke Grove from stops KE23, KF, KJ, KM St. -

Full Brochure

CONTENTS 04 Introduction 08 The History 20 The Building 38 The Materials 40 The Neighbourhood 55 Floor Plans 61 The Team 66 Contact 1 The scale of a full city block With its full city block setting, Marylebone Square is a rare chance to develop a bold and beautiful building on a piece of prime, storied real estate in a district rich in culture and history. Bound by Aybrook, Moxon, Cramer and St. Vincent Streets, Marylebone Square is reintroducing a long-lost local street pattern to the area. MARYLEBONE SQUARE INTRODUCTION A Rare London Find What is it about Marylebone? Perhaps it’s the elegance of its architecture and the charm of its boutiques and eateries – or the surprising tranquillity of its tree-lined streets, a world away from the bustle of nearby Oxford Street. In the end, it might be the sense of community and leisurely pace of life that sets this neighbourhood apart. As the city buzzes with its busy schedules, Marylebone takes its time – savouring sit-down coffees in local cafés and loungy lunches in the park. It’s easy to forget you’re just a short stroll away from transport hubs, tourist attractions and all the trappings of big city life. As you find yourself “Marylebone Square idling around the shops on chic Chiltern Street, exchanging hellos with the butcher at the Ginger Pig or sunbathing in a quiet corner of Paddington Square is a collection Gardens, you quickly realise that this is a place where people actually live – of 54 high-end not just commute to, pass through, or visit for a few hours a day. -

Star Wars at MT

NEW STAR WARS AT MADAME TUSSAUDS UNIQUE INTERACTIVE STAR WARS EXPERIENCE OPENS MAY 2015 A NEW multi-million pound experience opens at Madame Tussauds London in May, with a major new interactive Star Wars attraction. Created in close collaboration with Disney and Lucasfilm, the unique, immersive experience brings to life some of film’s most powerful moments featuring extraordinarily life- like wax figures in authentic walk-in sets. Fans can star alongside their favourite heroes and villains of Star Wars Episodes I-VI, with dynamic special effects and dramatic theming adding to the immersion as they encounter 16 characters in 11 separate sets. The attraction takes the Madame Tussauds experience to a whole new level with an experience that is about much more than the wax figures. Guests will become truly immersed in the films as they step right into Yoda's swamp as Luke Skywalker did in Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back or feel the fiery lava of Mustafar as Anakin turns to the dark side in Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith. Spanning two floors, the experience covers a galaxy of locations from the swamps of Dagobah and Jabba’s Throne Room to the flight deck of the Millennium Falcon. Fans can come face-to-face with sinister Stormtroopers; witness Luke Skywalker as he battles Darth Vader on the Death Star; feel the Force alongside Obi-Wan Kenobi and Qui-Gon Jinn when they take on Darth Maul on Naboo; join the captive Princess Leia and the evil Jabba the Hutt in his Throne Room; and hang out with Han Solo in the cantina before stepping onto the Millennium Falcon with the legendary Wookiee warrior, Chewbacca. -

St Marylebone Parish Church Records of Burials in the Crypt 1817-1853

Record of Bodies Interred in the Crypt of St Marylebone Parish Church 1817-1853 This list of 863 names has been collated from the merger of two paper documents held in the parish office of St Marylebone Church in July 2011. The large vaulted crypt beneath St Marylebone Church was used as place of burial from 1817, the year the church was consecrated, until it was full in 1853, when the entrance to the crypt was bricked up. The first, most comprehensive document is a handwritten list of names, addresses, date of interment, ages and vault numbers, thought to be written in the latter half of the 20th century. This was copied from an earlier, original document, which is now held by London Metropolitan Archives and copies on microfilm at London Metropolitan and Westminster Archives. The second document is a typed list from undertakers Farebrother Funeral Services who removed the coffins from the crypt in 1980 and took them for reburial at Brookwood cemetery, Woking in Surrey. This list provides information taken from details on the coffin and states the name, date of death and age. Many of the coffins were unidentifiable and marked “unknown”. On others the date of death was illegible and only the year has been recorded. Brookwood cemetery records indicate that the reburials took place on 22nd October 1982. There is now a memorial stone to mark the area. Whilst merging the documents as much information as possible from both lists has been recorded. Additional information from the Farebrother Funeral Service lists, not on the original list, including date of death has been recorded in italics under date of interment. -

Mystery on Baker Street

MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET BRUTAL KAZAKH OFFICIAL LINKED TO £147M LONDON PROPERTY EMPIRE Big chunks of Baker Street are owned by a mysterious figure with close ties to a former Kazakh secret police chief accused of murder and money-laundering. JULY 2015 1 MYSTERY ON BAKER STREET Brutal Kazakh official linked to £147m London property empire EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The ability to hide and spend suspect cash overseas is a large part of what makes serious corruption and organised crime attractive. After all, it is difficult to stuff millions under a mattress. You need to be able to squirrel the money away in the international financial system, and then find somewhere nice to spend it. Increasingly, London’s high-end property market seems to be one of the go-to destinations to give questionable funds a veneer of respectability. It offers lawyers who sell secrecy for a living, banks who ask few questions, top private schools for your children and a glamorous lifestyle on your doorstep. Throw in easy access to anonymously-owned offshore companies to hide your identity and the source of your funds and it is easy to see why Rakhat Aliyev. (Credit: SHAMIL ZHUMATOV/X00499/Reuters/Corbis) London’s financial system is so attractive to those with something to hide. Global Witness’ investigations reveal numerous links This briefing uncovers a troubling example of how between Rakhat Aliyev, Nurali Aliyev, and high-end London can be used by anyone wanting to hide London property. The majority of this property their identity behind complex networks of companies surrounds one of the city’s most famous addresses, and properties. -

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

Timeline: 2-14 Baker Street Date Event Notes

Timeline: 2-14 Baker Street Parties: British Land, McAleer & Rushe. Bank of Ireland, NAMA, Portman Estate Topic: 2-14 Baker Street - in London which was subject to a loan from Bank of Ireland Timeline: Date Event Notes August Several media articles report on This was the second reported purchase by and agreement between British Land and McAleer & Rushe from British Land – the September McAleer & Rushe for the sale (by BL) previous deal was for the Swiss Centre in 2005 of 2-14 Baker Street. Leicester Square. Guide price for the 2-14 Baker Street property was UK£47.5m with British Land offering it as a potential 150,000 sq. ft development opportunity. 5th 2-14 Baker Street purchased by Travers Smith acted for McAleer & Rushe October McAleer & Rushe by British Land for Group on the acquisition. 2005 UK£57.2m. The existing building tenants: Purchase funded with a Bank of Offices let on a lease expiring in December Ireland loan. 2009. Retail accommodation let under four separate leases all expiring by December 2009 The property comprised 94,000 sq. ft. held on a 98 year headlease from the Portman Estate. 16th Planning Application submitted to Planning application filed by Gerald Eve, December Westminster City Council listing Chartered Surveyors and Property Consultants 2008 Owners pf 2-14 Baker Street as: Contact person: James Owens 1. Portman Estate (freeholder) [email protected] 2. Mourant & Co Trustees Ltd and Mourant Property Trustees Ltd Baker Street Unit Trust is owned by McAleer & as Trustees of the Baker Street Rushe with a Jersey address. -

8904 SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 31St DECEMBER 1960

8904 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 31sT DECEMBER 1960 Most Excellent Order of the British Empire George Travis HARGREAVES, Esq., Intelligence (contd.) Officer, Grade I, British Services Security Ordinary Members of the Civil Division (contd.) Organisation, Germany. Joseph HARPER, Esq., Senior Executive Officer, Robin John GARLAND, Esq., Clerk to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Hamibledon Rural District Council, Surrey. George Albert HARRIS, Esq., M.V.O., Chief William Joseph GARRATT, Esq., J.P. For public Clerk, Central Chancery of the Orders of services in Staffordshire. Knighthood. Charles Joseph GAYTON, Esq., Higher Executive Henry HARTFORD, Esq., Higher Executive Officer, Officer, War Damage Commission. National Assistance Board. Miss Jean Wallace GEDDES, Head Teacher, Donald William HARVEY, Esq. For political ser- Phoenix Park Nursery School, Glasgow. vices in Cirencester and Tewkesbury. Gerard Henry GEILERN, Esq., Senior Warning George Thomas HARVEY, Esq., J.P., Chairman, Officer, York, United Kingdom Warning Aberdare Local Savings Committee. • Organisation. Harry Albert HASKELL, Esq., Chairman, Guild- Jean Margaret, Mrs. GENESE, Assistant Secretary ford and District War Pensions Committee. Royal Forestry Society of England and Wales. Edgar Warmiington HAWKEN, Esq., Senior Execu- The Reverend Spencer Walter GERHOLD, Rector, tive Officer, Air Ministry. S. Pierre Du Bois, Guernsey, Channel Islands. Percy James HAYDEN, Esq., lately Assistant For public services in Guernsey. Official Receiver, Board of Trade. John McDonald Frame GIBSON, Esq., Chairman, Godfrey HAYNES, Esq., Works Manager, Tyer East Renfrewshire Savings Committee. and Company, Ltd., Guildford. Thomas Arthur GIBSON, Esq., Clerk and Chief Harry HEAD, Esq., Trawler Skipper, Lowestoft. Fishery Officer, South Wales Sea Fisheries James Gerald HEAPS, Esq., Chief of Test and District Committee. -

BOARD of DEPUTIES of BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1944.Pdf

THE LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (iFOUNDED IN 1760) GENERALLY KNOWN AS THE BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1944 WOBURN HOUSE UPPER WOBURN PLACE LONDON, W.C.I 1945 .4-2. fd*׳American Jewish Comm LiBKARY FORM OF BEQUEST I bequeath to the LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (generally known as the Board of Deputies of British Jews) the sum of £ free of duty, to be applied to the general purposes of the said Board and the receipt of the Treasurer for the time being of the said Board shall be a sufficient discharge for the same. Contents List of Officers of the Board .. .. 2 List of Former Presidents .. .. .. 3 List of Congregations and Institutions represented on the Board .. .... .. 4 Committees .. .. .. .. .. ..10 Annual Report—Introduction .. .. 13 Administrative . .. .. 14 Executive Committee .. .. .. ..15 Aliens Committee .. .. .. .. 18 Education Committee . .. .. 20 Finance Committee . .. 21 Jewish Defence Committee . .. 21 Law, Parliamentary and General Purposes Committee . 24 Palestine Committee .. .. .. 28 Foreign Affairs Committee . .. .. ... 30 Accounts 42 C . 4 a פ) 3 ' P, . (OffuiTS 01 tt!t iBaarft President: PROFESSOR S. BRODETSKY Vice-Presidents : DR. ISRAEL FELDMAN PROFESSOR SAMSON WRIGHT Treasurer : M. GORDON LIVERMAN, J,P. Hon. Auditors : JOSEPH MELLER, O.B.E. THE RT. HON. LORD SWAYTHLING Solicitor : CHARLES H. L. EMANUEL, M.A. Auditors : MESSRS. JOHN DIAMOND & Co. Secretary : A. G. BROTMAN, B.SC. All communications should be addressed to THE SECRETARY at:— Woburn House, Upper Woburn Place, London, W.C.I Telephone : EUSton 3952-3 Telegraphic Address : Deputies, Kincross, London Cables : Deputies, London 2 Past $xmbmt% 0f tht Uoati 1760 BENJAMIN MENDES DA COSTA 1766 JOSEPH SALVADOR 1778 JOSEPH SALVADOR 1789 MOSES ISAAC LEVY 1800-1812 . -

Derwent London/Portman Estate Jv Completes Lettings at George Street Office

3PRESS RELEASE PRESS RELEASE 21 April 2008 Derwent London plc (“Derwent London”/ “Company”) DERWENT LONDON/PORTMAN ESTATE JV COMPLETES LETTINGS AT GEORGE STREET OFFICE Derwent London and The Portman Estate are pleased to announce that their joint venture company has completed two lettings of the entire office accommodation at the recently refurbished 100 George Street in Marylebone, London, W1. The Company has just completed a substantial refurbishment comprising a total of 13,119 sq ft (1,219 sq m) at basement, ground floor reception and first floor, together with a spectacular new penthouse office at fourth floor to create modern, well-designed offices created by ORMS Architects. The second and third floors at the property are residential. The details of the lettings are as follows: • London & Newcastle has taken 9,890 sq ft (919 sq m) at basement and first floor on a lease expiring in March 2018, at a rent of £60 per sq ft (£540,000 per annum), subject to a nine month rent free period and a review at the fifth year. • Argent Construction has taken the entire fourth floor, totalling 3,229 sq ft (300 sq m) on a lease expiring in March 2018, at a rent of £85 per sq ft (£274,465 per annum), subject to a five month rent free period and a review at the fifth year. Through the joint venture with The Portman Estate, George Street is part of Derwent London’s growing Baker Street and Marylebone portfolio, which forms part of its strategy to extend its presence in the villages immediately surrounding London’s West End. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Document.Pdf

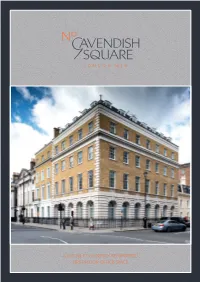

6,825 SQ FT OF NEWLY REFURBISHED FIRST FLOOR OFFICE SPACE Introducing 6,825 sq ft of newly refurbished, bright open plan office accommodation overlooking leafy Cavendish Square. CONVENIENTLY LOCATED WITH QUICK ACCESS ACROSS CENTRAL LONDON Oxford Circus Commissionaire Shower Newly Raised access 2 mins walk facilities and refurbished flooring WC spacious WCs to Cat A Bond Street* FLOOR PLAN 7 mins walk WC 6,825 sq ft Goodge Street 11 mins walk 643.06 sq m Suspended 3.4m floor to Excellent Fitted ceiling ceiling height natural light kitchenette *Elizabeth Line opens 2018 19 LOCAL AMENITIES NEW CAVENDISH STREET 15 1. The Wigmore 2. The Langham HARLEY STREET GLOUCESTER PLACE The Wallace 18 BBC 3. The Riding House Café Collection Broadcasting PORTLAND PLACE 6 House MARYLEBONE HIGH STREET 4. Pollen St Social BAKER STREET QUEEN ANNE STREET MANCHESTER SQUARE 5. Beast 19 2 3 10 PORTMAN SQUARE 8 MARYLEBONE LANE 1 6. The Ivy Café 16 7 17 7. Les 110 de Taillevent WIGMORE STREET CAVENDISH PLACE STREET CHANDOS 8. Cocoro Marble CAVENDISH Arch SQUARE 9. Swingers 14 19 11 HENRIETTA PLACE MARGARET STREET 10. Kaffeine DUKE STREET 9 11. Selfridges OXFORD STREET Bond Street 13 12. Carnaby St OXFORD STREET 5 13. John Lewis Oxford 14. St Christopher’s Place Circus PARK STREET REGENT STREET 15. Daylesford Bonhams NEW BOND STREET HANOVER SQUARE 16. Sourced Market GROSVENOR SQUARE BROOK STREET HANOVER STREET DAVIES STREET DAVIES 4 Liberty 17. Psycle GROSVENOR SQUARE 12 18. Third Space Marylebone MADDOX STREET 19. Q Park TERMS FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Sublease available until Matt Waugh Ed Arrowsmith December 2022 0207 152 5515 020 7152 5964 07912 977 980 07736 869 320 Rent on application [email protected] [email protected] Cushman & wakefield copyright 2018.