The Jazz-Blues Motif in James Baldwin's “Sonny's Blues”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocal Colour in Blue: Early Twentieth-Century Black Women Singers As Broadway's Voice Teachers

Document generated on 09/24/2021 8:30 p.m. Performance Matters Vocal Colour in Blue Early Twentieth-Century Black Women Singers as Broadway’s Voice Teachers Masi Asare Sound Acts, Part 1 Article abstract Volume 6, Number 2, 2020 This essay invokes a line of historical singing lessons that locate blues singers Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters in the lineage of Broadway belters. Contesting URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1075800ar the idea that black women who sang the blues and performed on the musical DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1075800ar stage in the early twentieth century possessed “untrained” voices—a pervasive narrative that retains currency in present-day voice pedagogy literature—I See table of contents argue that singing is a sonic citational practice. In the act of producing vocal sound, one implicitly cites the vocal acts of the teacher from whom one has learned the song. And, I suggest, if performance is always “twice-behaved,” then the particular modes of doubleness present in voice point up this Publisher(s) citationality, a condition of vocal sound that I name the “twice-heard.” In Institute for Performance Studies, Simon Fraser University considering how vocal performances replicate and transmit knowledge, the “voice lesson” serves as a key site for analysis. My experiences as a voice coach and composer in New York City over two decades ground my approach of ISSN listening for the body in vocal sound. Foregrounding the perspective and 2369-2537 (digital) embodied experience of voice practitioners of colour, I critique the myth of the “natural belter” that obscures the lessons Broadway performers have drawn Explore this journal from the blueswomen’s sound. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

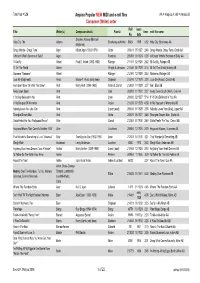

Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and E-Roll Files Composer

Total files = 536 Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and e-roll files AA = Ampico A, AB = Ampico B Composer (Writer) order Roll issue Title Writer(s) Composer details Pianist time midi file name No. date Stephen Adams (Michael Holy City, The Adams Brockway as Kmita 56824 1919 4:52 Holy City, Brockway AA Maybrick) Crazy Words - Crazy Tune Ager Milton Ager (1893-1979) Grofe 208611 05 1927 2:48 Crazy Words, Crazy Tune, Grofe AA I Wonder What's Become of Sally? Ager Fairchild 205191 09 1924 4:28 I Wonder What's Become of Sally AA I'll Get By Ahlert Fred E. Ahlert (1892-1953) Rainger 211171 02 1929 2:42 I'll Get By, Rainger AB I'll Tell The World Ahlert Wright & Johnston 211541 05 1929 3:14 I'll Tell The World (Ahlert) AB Marianne "Marianne" Ahlert Rainger 212191 12 1929 2:44 Marianne, Rainger AB Love Me (Deja) waltz Aivaz Morse-T. Aivaz (only item) Shipman 212241 12 1929 3:20 Love Me (Aivaz), Carroll AB Am I Blue? from "On With The Show" Akst Harry Akst (1894-1963) Arden & Carroll 212031 10 1929 3:37 Am I Blue AB Away Down South Akst Clair 203051 11 1922 2:37 Away Down South (Akst), Clair AA If I'd Only Believed In You Akst Lane 208383 02 1927 5:14 If I'd Only Believed In You AA In My Bouquet Of Memories Akst Arden 210233 07 1928 4:58 In My Bouquet of Memories AB Nobody Loves You Like I Do Akst Lopez (asst) 205531 01 1925 2:38 Nobody Loves You (Akst), Lopez AA Shanghai Dream Man Akst Grofe 208621 05 1927 3:48 Shanghai Dream Man, Grofe AA Gotta Feelin' For You "Hollywood Revue" Alter Carroll 212351 01 1930 2:49 Gotta Feelin' For You, Carroll AB Hugs and -

The Many Faces of “Dinah”: a Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of Its Recordings in the U.S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Many Faces of “Dinah” The Many Faces of “Dinah”: A Prewar American Popular Song and the Lineage of its Recordings in the U.S. and Japan Edgar W. Pope 「ダイナ」の多面性 ──戦前アメリカと日本における一つの流行歌とそのレコード── エドガー・W・ポープ 要 約 1925年にニューヨークで作曲された「ダイナ」は、1920・30年代のアメリ カと日本両国におけるもっとも人気のあるポピュラーソングの一つになり、 数多くのアメリカ人と日本人の演奏家によって録音された。本稿では、1935 年までに両国で録音されたこの曲のレコードのなかで、最も人気があり流 行したもののいくつかを選択して分析し比較する。さらにアメリカの演奏家 たちによって生み出された「ダイナ」の演奏習慣を表示する。そして日本人 の演奏家たちが、自分たちの想像力を通してこの曲の新しい理解を重ねる中 で、レコードを通して日本に伝わった演奏習慣をどのように応用していった かを考察する。 1. Introduction “Dinah,” published in 1925, was one of the leading hit songs to emerge from New York City’s “Tin Pan Alley” music industry during the interwar period, and was recorded in the U.S. by numerous singers and dance bands during the late 1920s and 1930s. It was also one of the most popular songs of the 1930s in Japan, where Japanese composers, arrangers, lyricists and performers, inspired in part by U.S. records, developed and recorded their own versions. In this paper I examine and compare a selection of the American and Japanese recordings of this song with the aim of tracing lines ─ 155 ─ 愛知県立大学外国語学部紀要第43号(言語・文学編) of influence, focusing on the aural evidence of the recordings themselves in relation to their recording and release dates. The analysis will show how American recordings of the song, which resulted from complex interactions of African American and European American artists and musical styles, established certain loose conventions of performance practices that were conveyed to Japan and to Japanese artists. It will then show how these Japanese artists made flexible use of American precedents, while also drawing influences from other Japanese recordings and adding their own individual creative ideas. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

Irving Berlin “This Is the Life!” The Breakthrough Years: 1909–1921 by Rick Benjamin “Irving Berlin remains, I think, America’s Schubert.” —George Gershwin It was a perfect late summer evening in 2015. A crowd had gathered in the park of a small Pennsylvania town to hear the high-school band. I was there to support my trombonist son and his friends. The others were also mostly parents and relatives of “band kids,” with a sprinkling of senior citizens and dog walkers. As the band launched its “covers” of current pop hits toward the treetops, some in the crowd were only half-listening; their digital devices were more absorbing. But then it happened: The band swung into a new tune, and the mood changed. Unconsciously people seemed to sit up a bit straighter. There was a smattering of applause. Hands and feet started to move in time with the beat. The seniors started to sing. One of those rare “public moments” was actually happening. Then I realized what the band was playing—“God Bless America.” Finally, here was something solid—something that resonated, even with these teenaged performers. The singing grew louder, and the performance ended with the biggest applause of the night. “God Bless America” was the grandest music of the concert, a mighty oak amongst the scrub. Yet the name of its creator—Irving Berlin—was never announced. It didn’t need to be. A man on a bench nearby said to me, “I just love those Irving Berlin songs.” Why is that, anyway? And how still? Irving Berlin was a Victorian who rose to fame during the Ragtime Era. -

Printed Music Collection (Single Sheet Music) Title Composer Publisher

Printed Music Collection (Single Sheet Music) Copyright / Publication Title Composer Publisher Date Physical description Other information Fine Art Edition, lyrics to the chorus are Daddy, You've Been A Mother To Me Fred Fisher McCarthy-Fisher Inc. 1920 9" x 12", 6 pages featured on the cover Dance of the "Whip-poor-whill", The Egbert Van Alstyne Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1910 10.5" x 13.5", 6 pages Popular Edition Dance of the Dwarfs Michael Aaron Harold Flammer, Inc 1928 9" x 12", 3 pages "Descriptive Educational Piano Pieces" lyrics by Harry B. Smith & Francis Dancing Fool Wheeler; music by Ted Snyder Waterson Berlin & Snyder Co. 1922 9" x 12", 2 pages Cover page only Danse Macabre (Symphonic Poem Camille Saint - Saens G. Schirmer, Inc 1934 9x12" 17 pages arr for piano by H. Cramer; edited by Carl Deis Ukelele arrangement by May Singhi Breen "The english lyrics by Joseph Kammen, music Ukelele Lady", featured by Emery Deutsch and Dark Eyes (Otchi-tchor-ni-ya, Очи ЧерньІR) by Jack Kammen J. & J. Kammen Music Co. 1929 9" x 12", 6 pages His Orchestra Darktown Strutters' Ball, The Shelton Brooks Leo Feist Inc. 1917 9" x 12", 6 pages Darling, Je Vous Aime Beaucoup Anna Sosenko Chappell & Co. Inc. 1935 9" x 12", 6 pages Featured by Hildegarde W. A. Mozart (English version by Dr. Th. Das Veilchen (The Violet) Baker) G. Schirmer Inc. 1903 9" x 12", 6 pages lyrics by Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby; Dawn music by Neil Moret Henry Waterson, Inc. 1925 9" x 12", 6 pages with ukelele arrangement by Jeanne Gravelle Day Dawn Polka, The T. -

CRAFTING a CAREER: ETHEL WATERS and CABIN in the SKY Briana Joy Frieda a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty at the University of No

CRAFTING A CAREER: ETHEL WATERS AND CABIN IN THE SKY Briana Joy Frieda A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology in the Music Department in the School of Music. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Jocelyn R. Neal Andrea Bohlman Chérie Ndaliko © 2015 Briana Joy Frieda ALL RIGHTS RESERV ED ii ABSTRACT Briana Joy Frieda: Crafting a Career: Ethel Waters and Cabin in the Sky (Under the direction of Jocelyn Neal) Ethel Waters (1896–1977) was a path-breaking African American entertainer whose career spanned nearly sixty years, moving from vaudeville to Hollywood. This thesis addresses the 1943 film Cabin in the Sky as a pivotal moment in Waters’s dramatic output, with her playing a role that served as culmination of the themes of her earlier career and as the transition to a new type of character. Beginning before Cabin , and moving through the end of her career, this analysis draws from biographical accounts in combination with close readings of the film to trace four main characteristics that govern her career and public persona: her assertion of creative control, her personal conflicts with female co-stars, her public expressions of religious piety, and her complex experiences with the racial politics of her era. Her oft-overlooked portrayal in Cabin offers insight into the tensions and contradictions that shaped her career and legacy. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 Writing Waters ........................................................................................................................ 3 Cabin in the Sky Summary ..................................................................................................... -

Tilo Hähnel, a Brief Portrait Of: Ethel Waters, October 4, 2012 Highschool of Music FRANZ LISZT Weimar Department of Musicology

Tilo Hähnel, a Brief Portrait of: Ethel Waters, October 4, 2012 Highschool of Music FRANZ LISZT Weimar Department of Musicology Weimar | Jena «Voices & Singing in Popular Music in the U.S.A. (1900–1960)» Research project funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) PF 669/4-1. Department of Musicology Weimar | Jena «Voices & Singing in Popular Music in the U.S.A. (1900–1960)»∗ a Brief Portrait of: ETHEL WATERS Tilo Hähnel Abstract «Sweet Mama Stringbean», as Waters was called in her early years, was a vaudeville star. Her singing style comprised a variety of vocal sounds and timbre, which she used to characterise the role she played on stage. She was able to scream and growl, but the most prominent features were a clear voice with a huge vibration, a clear pronunciation as well as an ironic and humorous approach to vocal expression. Her way to play with her voice seemed to be fun even for herself. Ethel Waters introduced many songs that became standards in the jazz repertoire, therefore she was one of the pioneers in jazz singing, too. 1 BIOGRAPHY Waters was born on 30th October, 1886 in Chester, Pennsylvania. In 1917 she entered the vaudeville stage and became famous in 1921 with her first recording «Down Home Blues». Her success was also a success for the record label Black Swan and was followed by a great tour through the US with Fletcher Henderson and Black Swan Masters. As a vaudeville star, Waters sung Blues and also recorded popular songs with the Columbia label since 1925 after Black Swan went bankrupt. -

Musical Movie Memories Discussion Guide for 1940S Music Run DVD Film Segments on a TV Or Projection TV System to an Assembled Group

DiMusicalscussion Guide forMovi 1920s-30se MusicMemories Run film segments one at a time on a TV or projection system. Pause on the 4 questions at the end of each so the viewers can respond and share their memories woken by the film. This Discussion Guide suggests additional questions to aid the session leader. All films in this special program are filled with music, singers and bands from the late 1920s through the 1930s. Music has proven helpful in bringing smiles and distant memories even to seniors with alzheimers. Unlike regular volumes of Movie Memories with their vast variety, there may not be that much to discuss with some of the films. You can tell by reactions whether the viewers enjoy the films. Standard questions which can be applied to each segment are: Did you like the song? Do you like jazz and swing bands? Do you remember ___________? Would you like to watch the film again? What is your favorite song from this era? Do you want to see more Bing Crosby musicals? Etc. Do not hesitate to ask these simple questions again and again! Disc #1 Al Jolson Trailers We just watched coming attractions for 3 Al Jolson films: Wonder Bar (1934), Go Into Your Dance (1935) and The Singing Kid (1936). These “trailers” showed the highlights of three of Al’s films from the mid-1930s. Have you ever see the first sound film -- The Jazz Singer -- with Al Jolson on TV? Do the trailers make you want to see the complete movies? Who are your favorite singers, stars or dancers from 1930s Hollywood musicals? Glorifying the American Girl This 1929 musical comedy was produced by Florenz Ziegfeld and highlights Ziegfeld’s current star, dancer Mary Eaton. -

James W. Phillips Collection

JAMES W. PHILLIPS COLLECTION RUTH T. WATANABE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SIBLEY MUSIC LIBRARY EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Processed by Gigi Monacchino, spring 2013 Revised by Gail E. Lowther, winter 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of Collection . 3 Description of Series . 5 INVENTORY Sub-Group I: Composer Subdivision Series 1: Irving Berlin . 7 Series 2: George Gershwin, Victor Herbert, and Jerome Kern . 35 Series 3: Jerome Kern and Cole Porter . 45 Series 4: Cole Porter and Richard Rodgers . 60 Series 5: Richard Rodgers . 72 Series 6: Richard Rodgers and Sigmund Romberg . 86 Sub-Group II: Individual Sheet Music Division . 92 Sub-Group III: Film and Stage Musical Songs . 214 Sub-Group IV: Miscellaneous Selections . 247 2 DESCRIPTION OF COLLECTION Accession no. 2007/8/14 Shelf location: C3B 7,4–6 Physical extent: 7.5 linear feet Biographical sketch James West Phillips (b. August 11, 1915; d. July 2, 2006) was born in Rochester, NY. He graduated from the University of Rochester in 1937 with distinction with a Bachelor of Arts in Mathematics; he was also elected to the academic honors society Phi Beta Kappa. In 1941, he moved to Washington, DC, to work in the Army Ordnance Division of the War Department as a research analyst. He left that position in 1954 to restore a house he purchased in Georgetown. Subsequently, in 1956, he joined the National Automobile Dealers Association as a research analyst and worked there until his retirement in 1972. He was an avid musician and concert-goer: he was a talented pianist, and he composed music throughout his life. -

Ella Fitzgerald Collection of Sheet Music, 1897-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p300477 No online items Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music, 1897-1991 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Bucher, Melissa Haley, Doug Johnson, 2015; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet PASC-M 135 1 music, 1897-1991 Title: Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music Collection number: PASC-M 135 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13.0 linear ft.(32 flat boxes and 1 1/2 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1897-1991 Abstract: This collection consists of primarily of published sheet music collected by singer Ella Fitzgerald. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. creator: Fitzgerald, Ella Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Music That Scared America: the Early Days of Jazz

Cover UNITED STATES HISTORY 1840-1930 Music That Scared America: The Early Days of Jazz Contents Cover Title Page Unit Introduction for Teachers Notes on the PDF California History-Social Science Standards Covered Key Terms PLEASE SEE Bibliography Student Worksheets NOTES ON THE List of Images PDF, PAGE 3. Acknowledgments Back Cover Title Page LESSONS IN US HISTORY By Matthew Mooney, Department of History, The University of California, Irvine Teacher Consultant, Sara Jordan, Segerstrom High, Santa Ana Additional feedback and guidance provided by Humanities Out There teacher partners Maria Castro and Roy Matthews (Santa Ana High School) and Chuck Lawhon (Century High School). Faculty Consultant, Alice Fahs, Associate Professor of History, The University of California, Irvine Managing Editor, Tova Cooper, Ph.D. The publication of this booklet has been made possible largely through funding from GEAR UP Santa Ana. This branch of GEAR UP has made a distinctive contribution to public school education in the U.S. by creating intellectual space within an urban school district for students who otherwise would not have access to the research, scholarship, and teaching represented by this collabora- tion between the University of California, the Santa Ana Partnership, and the Santa Ana Unified School District. Additional external funding in 2005-2006 has been provided to HOT by the Bank of America Foundation, the Wells Fargo Foundation, and the Pacific Life Foundation. THE UCI HISTORY-SOCIAL SCIENCE PROJECT The California History-Social Science Project (CH-SSP) of the University of California, Irvine, is dedicated to working with history teachers in Orange County to develop innovative approaches to engaging students in the study of the past.