Slave Trade URL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Ghanaian Kindergarten Teachers' Use of Bilingual and Translanguaging Practices Joyce Esi Bronteng University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School June 2018 A Study of Ghanaian Kindergarten Teachers' Use of Bilingual and Translanguaging Practices Joyce Esi Bronteng University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Pre- Elementary, Early Childhood, Kindergarten Teacher Education Commons Scholar Commons Citation Bronteng, Joyce Esi, "A Study of Ghanaian Kindergarten Teachers' Use of Bilingual and Translanguaging Practices" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7668 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of Ghanaian Kindergarten Teachers’ Use of Bilingual and Translanguaging Practices by Joyce Esi Bronteng A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Curriculum and Instruction with a concentration in Early Childhood Education Department of Teaching and Learning College of Education University of South Florida Major Professor: Ilene Berson, Ph.D. Michael Berson, Ph.D. Sophia Han, Ph.D. Lisa Lopez, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 25, 2018 Keywords: Bilingual Education, Classroom Displays, Iconic Signs, Mother Tongue-Based Bilingual Medium of Instruction, Paralanguage, Symbolic Sign, Translanguaging Copyright © 2018, Joyce Esi Bronteng DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the following: My late grandparents Papa Ekow Gyan and Maame Bɔlɔ Twema (a.k.a. -

Focus Expressions in Foodo∗

Focus Expressions in Foodo∗ Ines Fiedler Humboldt University of Berlin This paper aims at presenting different ways of expressing focus in Foodo, a Guang language. We can differentiate between marked and unmarked focus strategies. The marked focus expressions are first syntactically characterized: the focused constituent is in sentence-ini- tial position and is second always marked obligatorily by a focus mar- ker, which is nɩ for non-subjects and N for subjects. Complementary to these structures, Foodo knows an elliptic form consisting of the focused constituent and a predication marker gɛ́. It will be shown that the two focus markers can be analyzed as having developed out of the homophone conjunction nɩ and that the constraints on the use of the focus markers can be best explained by this fact. Keywords: focus constructions, scope of focus, focus types, Foodo 1 Introduction In my paper I would like to point out the various possibilities of expressing the pragmatic category of focus in Foodo. Foodo is spoken in a relatively small area within the province of Donga in the Northeast of Benin close to the border to Togo. The number of Foodo speakers is about 20 – 25,000 (cf. Plunkett 1990, ∗ The data presented here was elicited during field research conducted in March 2005 in Semere, Benin, as part of the project “Focus in Gur and Kwa languages” belonging to the Collaborative research centre SFB 632 “Information structure”, funded by the German Research Foundation, to which I express my thanks for enabling this field work. I’m very grateful to my informants from Semere. -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

Emmanuel Nicholas Abakah. Hypotheses on the Diachronic

1 Hypotheses on the Diachronic Development of the Akan Language Group Emmanuel Nicholas Abakah, Department of Akan-Nzema, University of Education, Winneba [email protected] Cell: +233 244 732 172 Abstract Historical linguists have already established the constituent varieties of the Akan language group as well as their relationships with other languages. What remains to be done is to reconstruct the Proto- Akan forms and this is what this paper sets out to accomplish. One remarkable observation about language is that languages change through time. This is not to obscure the fact that it is at least conceivable that language could remain unchanged over time, as is the case with some other human institutions e.g. various taboos in some cultures or the value of smile as a nonverbal signal. Be that as it may, the mutually comprehensible varieties of the codes that constitute the Akan language group have evidently undergone some changes over the course of time. However, they lack adequate written material that can take us far back into the history of the Akan language to enable any diachronic or historical linguist to determine hypotheses on their development. Besides, if empirical data from the sister Kwa languages or from the other daughters of the Niger-Congo parent language were readily available, then the reconstruction of the Proto-Akan forms would be quite straightforward. But, unfortunately, these are also hard to come by, at least, for the moment. Nevertheless, to reconstruct a *proto-language, historical linguists have set up a number of methods, which include the comparative method, internal reconstruction, language universals and linguistic typology among others. -

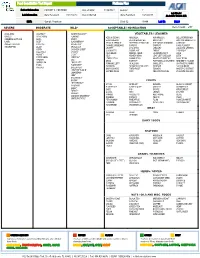

Platinum Plus Food Sensitivities Test Report

Food Sensitivities Test Report Platinum Plus Patient Information PATIENT II, PRETEND Date of Birth: 11/04/1977 Gender: F Lab Director Lab Information Date Received: 02/11/2010 Date Collected: Date Reported: 12/12/2017 Dr.Jennifer Spiegel, M.D. HCP: Sample Physician Clinic ID: 10804 Lab ID: 68220 SEVERE MODERATE MILD* ACCEPTABLE / NO REACTION Item Count: 237 AVOCADO ANCHOVY ACORN SQUASH* VEGETABLES / LEGUMES GARLIC ARTICHOKE ALMOND* ADZUKI BEANS ARUGULA ASPARAGUS BELL PEPPER MIX ICEBERG LETTUCE BASIL BISON* BLACK BEANS BLACK-EYED PEA BOK CHOY BOSTON BIBB LETTU LAMB BEEF BLACKBERRY* BRSSLS SPROUT BUTTERNUT SQUASH BUTTON MUSHROOM CABBAGE SWEET POTATO CATFISH BRAZIL NUT* CANNELLINI BEANS CAPERS CARROT CAULIFLOWER SWORDFISH CLAM BROCCOLI* CELERY CHICKPEA CHICORY COLLARD GREENS CORN CHICKEN LIVER* CUCUMBER EGGPLANT ENDIVE ESCAROLE EGG YOLK CHIVES* FAVA BEAN FENNEL SEED JALAPEÑO PEPP KALE MUSSEL CLOVE* KELP KIDNEY BEAN LEAF LETT (RED/GR LEEK PINTO BEAN CODFISH* LENTIL BEAN MUNG BEAN MUSTARD GREENS NAVY BEAN RADISH DILL* OKRA PARSNIP PORTOBELLO MUSHRM RED BEET / SUGAR SORGHUM EGG WHITE* ROMAINE LETT SCALLION SHALLOTS SHIITAKE MUSHRM TUNA FLOUNDER* SOYBEAN SPAGHETTI SQUASH SPINACH STRING BEAN WALNUT GREEN PEA* SWISS CHARD TARO ROOT TOMATO WATER CHESTNUT HONEYDEW MLN* WATERCRESS YAM YELLOW SQUASH ZUCCHINI SQUASH LIMA BEAN* LIME* MACADAMIA* ONION* FRUITS PEPPERMINT* APPLE APRICOT BANANA BLACK CURRANT RHUBARB* BLUEBERRY CANTALOUPE CHERRY CRANBERRY SAGE* DATE FIG GRAPE GRAPEFRUIT TURNIP* GUAVA KIWI LEMON LYCHEE VANILLA* MANGO MULBERRY NECTARINE OLIVE -

José Andrés Brings the Wonders of China and Peru to the Nation's

For immediate Release Contact: Maru Valdés (202) 638-1910 x 247 [email protected] José Andrés Brings the Wonders of China and Peru to the Nation’s Capital October 28, 2013 – José Andrés, the chef who introduced America to traditional Spanish tapas and championed the path of avant-garde cuisine in the U.S., is opening a modern Chinese- Peruvian concept, in the heart of Penn Quarter in downtown Washington, DC. The restaurant will feature Chifa favorites–the cuisine known throughout Peru, melding Chinese style and native ingredients–with his personal and creative take on Chinese classics and this South American style. José is no stranger to weaving cultures together in a dynamic dining experience, he is well known for his interpretation of Chinese and Mexican food, culture and traditions at his award-winning restaurant China Poblano at The Cosmopolitan of Las Vegas. At this new location, José and his talented culinary team will create authentic, yet innovative dishes inspired by their research and development trips to Asia and most recently to Peru, that have helped them master the various skills and techniques of this rising world cuisine. Highlighting the rich flavors, bold colors, diverse textures and unique aromas, the menu will apply time-honored Chinese techniques to Peruvian ingredients. From the classic Peruvian causas or ceviches, to Asian favorites like dim sums and sumais, the dishes will showcase Peru’s multi- cultural influences and ingredients in true Jose fashion. “Peru is an astonishing country. The people and the culture reveal so many traditions. The history with China is fascinating and the Chifa cuisine so unique,” said José. -

Focus Expressions in Foodo∗

Focus Expressions in Foodo∗ Ines Fiedler Humboldt University of Berlin This paper aims at presenting different ways of expressing focus in Foodo, a Guang language. We can differentiate between marked and unmarked focus strategies. The marked focus expressions are first syntactically characterized: the focused constituent is in sentence-ini- tial position and is second always marked obligatorily by a focus mar- ker, which is nɩ for non-subjects and N for subjects. Complementary to these structures, Foodo knows an elliptic form consisting of the focused constituent and a predication marker gɛ́. It will be shown that the two focus markers can be analyzed as having developed out of the homophone conjunction nɩ and that the constraints on the use of the focus markers can be best explained by this fact. Keywords: focus constructions, scope of focus, focus types, Foodo 1 Introduction In my paper I would like to point out the various possibilities of expressing the pragmatic category of focus in Foodo. Foodo is spoken in a relatively small area within the province of Donga in the Northeast of Benin close to the border to Togo. The number of Foodo speakers is about 20 – 25,000 (cf. Plunkett 1990, ∗ The data presented here was elicited during field research conducted in March 2005 in Semere, Benin, as part of the project “Focus in Gur and Kwa languages” belonging to the Collaborative research centre SFB 632 “Information structure”, funded by the German Research Foundation, to which I express my thanks for enabling this field work. I’m very grateful to my informants from Semere. -

Anufo Lessons

Peace Corps Anufo Workbook Oral proficiency Acknowledgement Peace Corps Togo is very pleased to present the first ever Anufo local language manual to Peace Corps Togo Trainees and Volunteers. This manual has become a reality due to the meticulous work of many people. The training team expresses its deepest gratitude to the Peace Togo Country Director Rebekah Brownie Lee having taken the initiative to have materials developed in local languages. His support is tremendous. The team is grateful to Peace Corps Togo Admin Officer, Kim Sanoussy and all the Administrative Staff for their logistical support and for having made funds available for this material development. A genuine appreciation to the language Testing Specialist Mildred Rivera-Martinez, the Training Specialist Rasa Edwards, to Stacy Cummings Technical Training Specialist, and all the Training Staff from the Center for their advice and assistance. A sincere gratitude to Peace Corps Togo Training Manager Blandine Samani-Zozo for her guidance and lively participation in the manual development. A word of recognition to all Peace Corps Volunteers who worked assiduously with the training team by offering their input. Congratulations to Trainers Salifou Koffi, Kossi Nyonyo, and the Training Secretary Jean B. Kpadenou who have worked diligently and conscientiously to develop this manual. i To the learner Congratulations to all of you Peace Corps Trainees and Volunteers for your acceptance to learn a new language. Of course learning a new language is not easy, but with dedication you will make it and achieve your goals. This manual is competency based and contains useful expressions related to all training components such as technique, health, safety and security. -

Laws of Attraction Northern Benin and Risk of Violent Extremist Spillover

Laws of Attraction Northern Benin and risk of violent extremist spillover CRU Report Kars de Bruijne Laws of Attraction Northern Benin and risk of violent extremist spillover Kars de Bruijne CRU Report June 2021 This is a joint report produced by the Conflict Research Unit of Clingendael – the Netherlands Institute of International Relations in partnership with the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). June 2021 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Julien Gerard Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the author Kars de Bruijne is a Senior Research Fellow with the Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit and a former Senior Researcher at ACLED. -

Uruguay - Country Fact Sheet

URUGUAY - COUNTRY FACT SHEET GENERAL INFORMATION Climate & Weather Summers and Winters Time Zone UTC – 3 hrs. are mild. Summer is from December to March and the most pleasant time of the year. Language Spanish. Currency UYU – Uruguayan Peso. Religion Catholic. International +598 Dialing Code Population 3,442,547 as of 2016. Internet Domain .uy Political System Presidential representative Emergency 911 democratic republic. Numbers Electricity 220 volts, 50 cycles/sec. Capital City Montevideo. What documents Passport, work permit Please confirm Monthly directly into a bank required to open (can’t be done prior to how salaries are account. a local Bank arrival as expats usually paid? (eg monthly Account? aren’t granted their work directly into a Can this be done permits until 2-3 weeks Bank Account) prior to arrival? after they arrive to start their assignments. 1 GENERAL INFORMATION Culture/Business Culture Meetings are extremely formal, but don't usually start on time. However, be sure to arrive on time. Greetings are warm and accompanied by a firm handshake. Health care/medical There is a public healthcare system, with hospitals and clinics across treatment the country. There is also a private healthcare system. Education Public schools are not recommended in Uruguay and most assignees chose private schools, however there are limitations in the availability in the private schools. Utilities Electricity, Gas, Water, Internet, Phone, Cable. These are not included in monthly rent and paid separately by the tenant. Food & Drink Uruguayan cuisine has a lot of European influence, especially from Italy and Spain. Chivito is a traditional Uruguayan sandwich. -

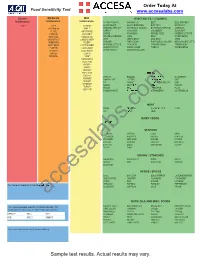

Sample Test Results. Actual Results May Vary. Order Today at Food Sensitivity Test 4 Day Rotation Diet

Order Today At Food Sensitivity Test www.accesalabs.com Severe Moderate Mild VEGETABLES / LEGUMES Intolerance Intolerance Intolerance !"# $ FRUITSTS # MEAT DAIRY / EGGS SEAFOOD abs.comab GRAINS / STARCHES HERBS / SPICES cesala You have no reaction to Candidaa Albicans.acceac NUTS/ OILS AND MISC. FOODS $ You have a severe reaction to Gluten/Gliadin, The foods listed below contain Gluten/Gliadin eliminate these foods: % # $ You have no reaction to Casein or Whey. Sample test results. Actual results may vary. Order Today At Food Sensitivity Test www.accesalabs.com 4 Day Rotation Diet DAY 1 DAY 2 DAY 3 DAY 4 STARCH STARCH STARCH STARCH VEGETABLES/LEGUMES VEGETABLES VEGETABLES VEGETABLES ! "##$% FRUIT FRUIT FRUIT FRUIT PROTEIN PROTEIN PROTEIN PROTEIN MISCELLANEOUSS MMISCELLANEOUS MISCELLANEOUS MISCELLANEOUS -

Making Investment Work for Africa: a Parliamentarian Response to “Land Grabs” July 21–22, 2011 Pan African Parliament, Midrand, South Africa

P PAN AFRICAN PARLEMENT P PARLIAMENT PANAFRICAIN -PARLAMENTO PAN البرلمان اﻷفريقي AFRICANO Making Investment Work for Africa: A parliamentarian response to “land grabs” July 21–22, 2011 Pan African Parliament, Midrand, South Africa Report from the seminar on foreign investment in agricultural land and water, organized by the Pan African Parliament in collaboration with the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS). The seminar was made possible through the generous support of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). October 2011 Making Investment Work for Africa: A parliamentarian response to “land grabs” Foreward by Joaquim Alberto Chissano, Former President of Mozambique and Chairman of the Africa Forum “I pressed my father’s hand and told him I would protect his grave with my life. My father smiled and passed away to the spirit land.” Chief Joseph of the wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) Indian Humanitarian and Peacemaker March 3, 1840–September 21, 1904 The report from the seminar Making Investment Work for Africa, organized by the Pan African Parliament in Midrand, South Africa from July 21-22, 2011, contains important recommendations on how best to implement the overall objectives of the Maputo Declaration commitments on the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), adopted in Maputo, the Republic of Mozambique, in 2003. The seminar, the first of its kind, organized in collaboration with the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS), brought together 40 parliamentarians, representatives from intergovernmental agencies including the African Union (AU) and the NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the African Development Bank, donor community, academics and a vibrant civil society.