The Poor and Voluntary Long Term Contractual Savings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equity-Fund.Pdf

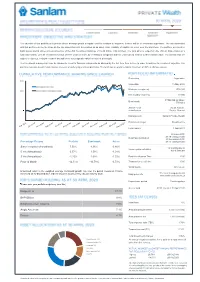

The objective of this portfolio is to provide above average growth in capital over the medium to long term. Income will be of secondary importance. The risk associated with this portfolio will be the same as the risk associated with SA equities as an asset class. Volatility of capital can occur over the short term. The portfolio will invest in liquid assets and in shares across all sectors of the JSE Securities Exchange of South Africa, (JSE Limited). The fund aims to outperform the JSE All Share Index on a total return basis, over an investment horizon of three years or more, by investing in companies that are undervalued relative to their intrinsic value. The investments are subject to rigorous, in-depth research and adhere to our pragmatic value investment philosophy. The investment manager will also be allowed to invest in financial instruments as allowed by the Act from time to time in order to achieve its investment objective. The portfolio may also invest in participatory interests of underlying unit trust portfolios. The fund may at any time hold a maximum of 30% in offshore assets. Risk rating Aggressive Issue date 16 May 2020 Minimum investment R30 000 Min monthly recurring R1000 FTSE/JSE All Share Benchmark TR Index ASISA Fund South African– classification Equity -General Management Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolio manager David Lerche Fund launch 1 April 2011 30 June 2019: 23.49 cents per unit Bi-annual distribution 31 December 2019: Percentage Returns Portfolio Benchmark Active 28.47 cents per unit Since Inception (Annualised) 7.50% 8.36% -0.86% 1st working day in Income payment dates 5 Yrs (Annualised) 0.57% 1.58% -1.01% July & January 3 Yrs (Annualised) -1.25% 1.08% -2.33% Portfolio valuation Time 15:00 Past 12 Month -14.51% -10.78% -3.73% Transaction cut-off time 15:00 Withdrawals On request Annualised return is the weighted average compound growth rate over the period measured. -

George Hallett

GEORGE HALLETT Born 1942, District Six, Western Cape, South Africa Lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa EDUCATION 1959-63 Artists’ Cooperative Workshop Apprenticeships at Art Foundry of Block and Leo Wald, Sculpture, Pottery, and Plastics 1967 Transvaal Art Academy 1980-83 Graduate Programme in Film and Television, New York University 1986 Visiting Artist, University of Massachusetts SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 George Hallett, Gallery MOMO, Johannesburg, South Africa 2018 George Hallett, Gallery MOMO Cape Town, South Africa 2013 George Hallett: A Nomad’s Harvest, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa 2010 1994 Elections and Mandela’s Vision, various locations, Germany Impressions of Italy, Artscape, Cape Town, South Africa Portraits from Exile, Bonhams, London 2007 Portraits of African Writers, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa 2006 Portraits of African Writers, Cape Town International Book Fair, Cape Town, South Africa 2005 South African Exiles of the ‘70s and ‘80s in Europe, Spitz Gallery, London 2004 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Exhibition, Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry, UK 2001 Dance for All, The Aschegach Gallery, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2000 Dance for All, Maidenhead Cultural Centre, UK 1999 The Face of Bo-Kaap, Bo-Kaap Museum, Cape Town, South Africa 1995 Transformation, 1994 Elections, Irma Stern Museum, Cape Town, South Africa 1989 Afrika Centrum, Cadier en Keer, Maastricht, Netherlands 1988 Künstforum der Sozialdemokratie, Bonn, Germany 1985 University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, -

Sanlam Global Funds Plc

SANLAM GLOBAL FUNDS PLC SANLAM GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Unaudited condensed interim financial statements for the six months ended 30 June 2020 SANLAM GLOBAL FUNDS PLC UNAUDITED CONDENSED INTERIM FINANCIAL STATEMENTS for the six months ended 30 June 2020 Contents Page(s) Company information 1 - 4 Directors’ report 5 - 10 Economic & market review 11 - 13 Investment Manager’s reports 14 - 39 Statement of comprehensive income of the Company 40 of the Funds 41 - 48 Statement of financial position of the Company 49 of the Funds 50 - 57 Statement of changes in net assets attributable to participating shareholders of the Company 58 of the Funds 59 - 66 Statement of cash flows of the Company 67 of the Funds 68 - 75 Portfolio of investments Sanlam Global Balanced Fund 76 Sanlam Global Equity Fund 77 Sanlam BIFM World Equity Fund 78 Sanlam BIFM Global Fixed Income Fund 79 Mpile Global Equity Fund 80 Sanlam Private Wealth Global Balanced Fund 81 - 82 Counterpoint Global Equity Fund 83 - 85 Independent Global Flexible Fund 86 - 87 Counterpoint Global Owner Managed Flexible Fund 88 - 89 Excalibur Global Managed Fund 90 Northstar Global Flexible Fund 91 - 93 Absa Global Best Blend Fund 94 Absa Global Access Fund 95 Notes to and forming part of the unaudited condensed interim financial statements 96 - 128 AIFMD Periodic Disclosures 129 SANLAM GLOBAL FUNDS PLC COMPANY INFORMATION Directors of Sanlam Global Paul Dobbyn1 – Irish Funds Plc (the “Company”) Thomas Murray1 – Irish Haydn Franckeiss – South African Richard Aslett – British All Directors are non-executive -

Khayelitsha Western Cape Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & Dplg, 2007 Khayelitsha Context

Nodal Economic Profiling Project Khayelitsha Western Cape Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & dplg, 2007 Khayelitsha Context IInn 22000011,, SSttaattee PPrreessiiddeenntt TThhaabboo MMbbeekkii aannnnoouunncceedd aann iinniittiiaattiivvee ttoo aaddddrreessss uunnddeerrddeevveellooppmmeenntt iinn tthhee mmoosstt sseevveerreellyy iimmppoovveerriisshheedd aarreeaass rruurraall aanndd uurrbbaann aarreeaass ((““ppoovveerrttyy nnooddeess””)),, wwhhiicchh hhoouussee aarroouunndd tteenn mmiilllliioonn ppeeooppllee.. TThhee UUrrbbaann RReenneewwaall PPrrooggrraammmmee ((uurrpp)) aanndd tthhee IInntteeggrraatteedd SSuussttaaiinnaabbllee RRuurraall Maruleng DDeevveellooppmmeenntt PPrrooggrraammmmee Sekhukhune ((iissrrddpp)) wweerree ccrreeaatteedd iinn 22000011 Bushbuckridge ttoo aaddddrreessss ddeevveellooppmmeenntt iinn Alexandra tthheessee aarreeaass.. TThheessee iinniittiiaattiivveess Kgalagadi Umkhanyakude aarree hhoouusseedd iinn tthhee DDeeppaarrttmmeenntt ooff PPrroovviinncciiaall aanndd Zululand LLooccaall GGoovveerrnnmmeenntt ((ddppllgg)).. Maluti-a-Phofung Umzinyathi Galeshewe Umzimkhulu I-N-K Alfred Nzo Ukhahlamba Ugu Central Karoo OR Tambo Chris Hani Mitchell’s Plain Mdantsane Khayelitsha Motherwell UUP-WRD-Khayelitsha Profile-301106-IS 2 Nodal Economic Profiling Project Business Trust & dplg, 2007 Khayelitsha Khayelitsha poverty node z Research process Activities Documents z Overview People z Themes – Residential life – Commercial activity – City linkages z Summary z Appendix UUP-WRD-Khayelitsha Profile-301106-IS 3 Nodal -

The Youth Book. a Directory of South African Youth Organisations, Service Providers and Resource Material

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 432 485 SO 029 682 AUTHOR Barnard, David, Ed. TITLE The Youth Book. A Directory of South African Youth Organisations, Service Providers and Resource Material. INSTITUTION Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria (South Africa). ISBN ISBN-0-7969-1824-4 PUB DATE 1997-04-00 NOTE 455p. AVAILABLE FROM Programme for Development Research, Human Sciences Research Council, P 0 Box 32410, 2017 Braamfontein, South Africa; Tel: 011-482-6150; Fax: 011-482-4739. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Developing Nations; Educational Resources; Foreign Countries; Schools; Service Learning; *Youth; *Youth Agencies; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Service Providers; *South Africa; Youth Service ABSTRACT With the goal of enhancing cooperation and interaction among youth, youth organizations, and other service providers to the youth sector, this directory aims to give youth, as well as people and organizations involved and interested in youth-related issues, a comprehensive source of information on South African youth organizations and related relevant issues. The directory is divided into three main parts. The first part, which is the background, is introductory comments by President Nelson Mandela and other officials. The second part consists of three directory sections, namely South African youth and children's organizations, South African educational institutions, including technical training colleges, technikons and universities, and South African and international youth organizations. The section on South African youth and children's organizations, the largest section, consists of 44 sectoral chapters, with each organization listed in a sectoral chapter representing its primary activity focus. Each organization is at the same time also cross-referenced with other relevant sectoral chapters, indicated by keywords at the bottom of an entry. -

Sanlam 2020 About Us

0202 Sanlam Integrated Report 2020 A snapshot of Sanlam // A snapshot of Sanlam About us Sanlam was established as a life insurance company in South Africa but has since transformed into a diversified financial services group operating across Africa, India and selected emerging and developed markets, with listings on the Johannesburg, A2X and Namibian stock exchanges. The Group has been operating for more than 100 years, most of which as a mutual insurer. Sanlam demutualised and listed on the Johannesburg and Namibian stock exchanges in 1998. e offer our clients a large and diversified Our purpose is to empower generations range of solutions. Omni-channel distribution ensures that clients are reached and serviced to be financially confident, secure and through their preferred channel, with prosperous. Our vision is to distinguish increased focus on developing our digital ourselves as the most admired financial capability. Read more on page 10. services group in Africa. Our purpose W and vision is enabled through our Our main sources of earnings are the net operating profit strategy, which we discuss in more (net result from financial services) we earn from our different lines of business and the net income we earn from investing detail on page 30. our capital in the financial markets (net investment return). Current and expected future growth in these sources of Our strategy guides our long-term earnings is the main driver behind shareholder value creation as measured by Return on Group Equity Value (RoGEV), our thinking. main financial performance indicator. Read more about the drivers behind our main sources of earnings and RoGEV from page 67. -

Newsletter No. 42

NEWSLETTER 42 2014/15 tO OUR www.abalimi.org.za Co-ordinating Office:c\o The Business Place Philippi, Cwango Crescent (Cnr New www.harvestofhope.co.za Eisleben Rd and Lansdowne Rd, behind Shoprite Centre) Philippi, 7785, Cape Town, FRIENDS www.farmgardentrust.org PO Box 44, Observatory, 7935. 021 3711653 Fax: 086 6131178 Khayelitsha Garden Centre 021 3613497 Nyanga Garden Centre 021 3863777 Seeds grow and become seedlings, which become tasty mama pat PaSses FlAme nutritious vegetables. Seeds also give birth to other seeds and so keep going the magic To her graNddaughteR cycle of life. a larger micro-farm soon. Zandile is proud of her first harvest for HoH (Harvest of Hope) last September. She attended the training of ABALIMI and then took the course of Applied Permaculture Training at SEED. “I am happy to be part of the community of ABALIMI farmers. I know that ABALIMI wants more young people as farmers and I am proud to be part of this new young micro- farming generation” she said. Her grandmother, Mama Patricia Palishe, is her inspiration. Mama Pat has her own garden in Khayelitsha which keeps her healthy and active. mama paT “I don’t want to stay sitting at home. I need ZaNDIlE to keep moving, wake up in the morning and always be fresh up. I do not sit and wait for death!” ABALIMI BEZEKHAYA inspires the Youth to take up the farming life just like their elders did before them. Hard work does not put off The two women often work together in Mama Pat’s garden and also the ambitious young women and men that now come to train to be help out in the HoH packshed. -

Commercial Property Report Master

COMMERCIAL PROPERTY REPORT February 2016 This report highlights property transactions with a value of more than R5million that have occurred since January 2012 and should be viewed in conjunction with the Property section in www.sarevealed.co.za which carries all the transactions in a spatial environment. SA Revealed has taken every care in compiling information and material for this report, but will not be held responsible for any loss, damage or inconvenience caused as a result of any inaccuracy or error contained in this report Tel: +27 11 463 6327Fax: +27 11 706 1804www.sarevealed.co.za Moraine House, The Braes,193 Bryanston Drive Bryanston, Johannesburg, South Africa SA Revealed (Pty) Ltd Registration Number 2011/112308/07 OVERVIEW OF REPORT AND WEBSITE This COMMERCIAL PROPERTY REPORT and the PROPERTY section of the SA Revealed website www.co.za should be used in conjunction, and provides a comprehensive view of the Commercial Property environment in South Africa EVERYTHING IN THE REPORT CAN BE EXAMINED IN DETAIL ON THE WEBSITE The website is updated by the fifth of every month and the report is published by the tenth of the month. The updates are governed by the feed date of the transactions from the Deeds Office The segmentation of location ³Node´ and buyer ³Owner´ are reflected in the Report and can be viewed by selection on the Website Large Transactions and Large Bonds ±These sections of the website focus on data from January 2013, where the property owner is a non-person, and the purchase or bond value is greater than R5million. -

Cape Town Philharmonic U.S. Tour Brochure

CAPE TOWN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA UNITED STATES TOUR 12 February – 6 March 2011 Daytona Beach (FL) Sarasota (FL) Avon Park (FL) Vero Beach (FL) Palm Beach (FL) Fort Lauderdale (FL) Gainesville (FL) St Augustine (FL) Clemson (SC) Platteville (WI) Kansas City (MO) Lincoln (NE) Ames (IA) Worcester (MA) Lancaster (PA) Lewisburg (PA) Lansdale (PA) Geneva (NY) CAPE TOWN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA SOUTH AFRICA CAPE TOWN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA CAPE TOWN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA CAPE TOWN FOUNDING DONORS GOLD BENEFACTORS PHILHARMONIC (R500 00 – R999 999) (R10 000 –R49 999) ORCHESTRA Artscape ADMINISTRATION: Caltex Friends of Orchestral Music A & M Pevsner Charitable Trust City of Cape Town Joan St Leger Lindbergh Ackerman Family Trust CHIEF EXECUTIVE: Caroline van Zyl Charitable Trust* Alma Finch Louis Heyneman Department of Arts & Culture Michael Blersch Estate Altron Distell Old Mutual Anonymous ARTISTIC EXECUTIVE: Jan S de Villiers PriceWaterhouseCoopers (in memory of Mrs Rupert) CAPE TOWN Sergei Burdukov Naspers (in kind) Anonymous PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Robin Hamilton Rand Merchant Bank Fund (in loving memory of CORPORATE Rupert-Musiekstigting Rolf-Stephan Nussbaum Rosanna Strauss) FUNDRAISING EXECUTIVE: Sanlam Foundation Austrian Consulate General Karin Blumer Ton Vosloo Werksmans (in kind) Brian Dix-Hart Estate Western Cape Cultural Cedric Reid GENERAL MANAGER: Commission *managed by BOE Private Clients Consol Glass CAPE TOWN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Ivan Christian Count & Countess Labia PARTNERS SILVER Delia Scott PR & MARKETING MANAGER: (Cumulative -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 | 2017 is an isiXhosa word, meaning • South African Museum and Planetarium IZIKO ‘hearth’, traditionally and • South African National Gallery symbolically the social centre of the home; a place • Maritime Centre, including the museum ship, associated with warmth, kinship and ancestral SAS Somerset spirits. Here food is prepared and shared, stories • Slave Lodge Museum are told and knowledge passed from one generation • William Fehr Collection (at the Castle of Good Hope) Photographs for this report supplied by: to the next. Similarly, the museums that make up • Michaelis Collection (at the Old Town House) Sky-Skan: Front cover; inside front cover; title page; Iziko are spaces for cultural interaction. We are • Rust en Vreugd Museum 2–3; 4–5; 22–23; 34–35; 51–51; 64–65; 134–135; proud to ignite connections between our shared • Bertram House Museum inside back cover; back cover history, our heritage, and each other. • Koopmans-de Wet House Museum • Groot Constantia Museum Iziko Photographer, Nigel Pamplin: 8–9; 10; 12; 14–15; 18 b; 19; 46–47; 48–49; 56–57; 58; 67; 136–137; • Bo-Kaap Museum 138–139; 142; 143; 146 b; 150 a; Marc Smith (UCT Honours in Curatorship student): 18 a Jonathan Riordan: 146 a; 147 b Thando Ngcangisa: 151 a CONTENTS 1 General Information 4 5 Financial Information 64 1.1 Strategic Overview 6 Statement of Responsibility 66 1.2 Legislative and Other Mandates 7 Report of the Audit and Risk Committee 67 1.3 Organisational Structure 8 Report of the Auditor-General 70 1.4 Foreword by the Chairman 10 Accounting -

(021) 6971613 6070078 Western Cape Athlone Cape Town 31

CONTACT PRACTICE PROVINCE PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL ADDRESS PHARMACY NAME NUMBER NUMBER WESTERN CAPE ATHLONE CAPE TOWN 29 OLD KLIPFONTEIN ATHLONE PHARMACY (021) 6971613 6070078 ROAD WESTERN CAPE ATHLONE CAPE TOWN 31 LAWRENCE ROAD BRAUDES PHARMACY (021) 6969820 612219 WESTERN CAPE ATHLONE CAPE TOWN VANGUARD DRIVE CLICKS PHARMACY VANGATE (021) 6381289 227951 MALL WESTERN CAPE ATHLONE CAPE TOWN 111 REPULSE ROAD FIR-KEM PHARMACY (021) 6911142 6045901 WESTERN CAPE ATHLONE CAPE TOWN CORNER HAZEL AND MEDIGATE DISPENSARY (021) 6378824 6083471 CLINIC ROADS WESTERN CAPE ATHLONE CAPE TOWN 77 BELGRAVIA ROAD MEDI-KEM PHARMACY ATHLONE (021) 6967557 70343 WESTERN CAPE ATLANTIS CAPE TOWN INNERING STREET ATLANTIS PHARMACY (021) 5725552 441694 WESTERN CAPE ATLANTIS CAPE TOWN WESFLEUR CIRCLE CLICKS PHARMACY ATLANTIS (021) 5723496 618136 WESTERN CAPE ATLANTIS CAPE TOWN CORNER ARION AND MEDIRITE PHARMACY ATLANTIS (021) 5728921 182354 RYGERSDAL ROADS WESTERN CAPE AURORA DURBANVILLE CORNER BURTON AND PHARMACY@SPAR AURORA (021) 9760570 615145 AURORA STREETS WESTERN CAPE BEACON VALLEY MITCHELLS PLAIN 17 KORFBAL STREET CHEMCARE PHARMACY (021) 3765805 426547 WESTERN CAPE BEAUFORT WEST BEAUFORT WEST CORNER DANIE THERON CLICKS PHARMACY BEAUFORT (023) 4153042 390526 AND N1 ROADS WEST WESTERN CAPE BEAUFORT WEST BEAUFORT WEST 47 DONKIN STREET NUWEVELD PHARMACY (023) 4142152 6000150 WESTERN CAPE BELHAR BELHAR CORNER BELHAR AND BEL- AIR PHARMACY (021) 9526129 452645 STELLENBOSCH DRIVES GEMS REO NETWORK PHARMACY – WESTERN CAPE Page 1 of 28 CONTACT PRACTICE -

Access the Repository

REGENT BUSINESS SCHOOL Data Base of all Research and Research Presentations and Allied Research Activities conducted by the REGENT Business School’s Directorate of Research and Innovation for the period 2002 to December 2016: A REPOSITORY OF ALL RESEARCH CONDUCTED AND UNDERTAKEN 1. INTRODUCTION Humble beginnings by REGENT Business School in Respect to Research: Advancing the South African Research Agenda Against all Odds in a Sustained, Coordinated and Professional Manner. It is our pleasure to document all of the research and allied activities including journal articles published and, undertaken by the REGENT Business School for the period 2002 to December 2016 (A period of 14 Years). It was a difficult task to assemble the data because, this exercise was conducted for the first time and, some of the data was not easily accessible going back to the year 2002, or was not on record within the school. The initial years saw the school finding its feet and, it was a period when research was at a very rudimentary stage and level of development and engagement. i In spite of the difficulties encountered in assembling the data, it was an exercise and, effort that achieved the desired effect of obtaining the maximum data of most of the research conducted by the institution, including allied research activities, over a period of nearly two decades. It was a grueling exercise and we are happy with our efforts of creating a more than adequate data base for scrutiny by management, staff, and outside organizations and formations, including the regulatory authority in the form of the Council on Higher Education (CHE) and the Department of Higher Education.