University of Cape Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Velop C in Pmen Confe Nform Nt Des Erence Matio Sign R E 201 On

Weebsite: design‐development‐research.co.za Development Design Research Conference 2014 Information Pack The Faculty of Informatics & Design at Cape Peninsula University of Technology welcomes you to Cape Town!! Cape Town has been awarded the World Design Capital for 2014, and our legendary and well renowned Table Mountain proclaimed as the newest Wonder of the Nature. We trust that your stay with us in the beautiful Mother City is one filled with new‐found adventures and experiences; that will capture your heart and ensure that this is the first of many more visits to our amazing city of Cape Town. This pack contains the following information you will need to know to thoroughly enjoy your stay with us: Accommodation Car Hire Car Rental Airport Shuttles MyCiti Bus Services Shuttle Services Foreign Exchange Bureau’s Map of Cape Town CBD Tourist and Sightseeing Options Restaurant Options Weather, Health, Safety & Other Accommodation: Lady Hamilton Hotel (Cape Town): Excellent Guest House offers luxury, comfort, style and warmth at affordable prices, situated in the Bellville area. The Guest House is suitable for business people, tourists and even South Africans visiting family in the area. Excellent Guest House has a quite, relaxing atmosphere with 23 tastefully furnished double rooms with showers en‐suite. The suites are equipped with hot and cold air conditioners, Satellite TV, coffee‐making facilities, a safe, hairdryers and other touches to make your stay as comfortable as possible. Each room has a parking bay conveniently situated outside the room, and guests have 24/7 accesses to the electronic gates. Our rooms are serviced daily and a laundry service is available at an additional cost. -

Somalinomics

SOMALINOMICS A CASE STUDY ON THE ECONOMICS OF SOMALI INFORMAL TRADE IN THE WESTERN CAPE VANYA GASTROW WITH RONI AMIT 2013 | ACMS RESEARCH REPORT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research report was produced by the African Centre for Migration & Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with support from Atlantic Philanthropies. The report was researched and written by Vanya Gastrow, with supervision and contributions from Roni Amit. Mohamed Aden Osman, Sakhiwo ‘Toto’ Gxabela, and Wanda Bici provided research assistance in the field sites. ACMS wishes to acknowledge the research support of various individuals, organisations and government departments. Abdi Ahmed Aden and Mohamed Abshir Fatule of the Somali Retailers Association shared valuable information on the experiences of Somali traders in Cape Town. Abdikadir Khalif and Mohamed Aden Osman of the Somali Association of South Africa, and Abdirizak Mursal Farah of the Somali Refugee Aid Agency assisted in providing advice and arranging venues for interviews in Bellville and Mitchells Plain. Community activist Mohamed Ahmed Afrah Omar also provided advice and support towards the research. The South African Police Service (SAPS) introduced ACMS to relevant station commanders who in turn facilitated interviews with sector managers as well as detectives at their stations. Fundiswa Hoko at the SAPS Western Cape provincial office provided quick and efficient coordination. The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development facilitated interviews with prosecutors, and the National Prosecuting Authority provided ACMS with valuable data on prosecutions relating to ‘xenophobia cases’. ACMS also acknowledges the many Somali traders and South African township residents who spoke openly with ACMS and shared their views and experiences. -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

What Is a General Valuation Roll?

General Valuation 2018 (GV2018) What is a General Valuation Roll? A General Valuation Roll is a document containing the municipal valuations of about 875 000 registered properties within the boundaries of Cape Town. All properties on the GV Roll are valued at market value as of the date of valuation. Every municipality is legally required to produce a General Valuation Roll at least once every four years but the City of Cape Town produces theirs every three years, to help mitigate big fluctuations in property values. General Valuation Roll for 2018 (GV2018)? The GV2018 Roll is scheduled to be certified by the municipal valuer on 31 January 2019 and will be implemented together with the approved budget on 1 July 2019. The valuation of all properties on the GV2018 Roll is determined according to market conditions on the date of valuation as at 2 July 2018. The rate-in-the-rand to be taxed against property values, will be determined by Council in March 2019, together with the tabling of the budget. This will enable us to fund municipal services as outlined in the Integrated Development Plan. Please note: property valuations are determined objectively and according to market values. They are an indication in the growth of the value of the property and while the valuation is used to determine the rates income for the City, it is not an arbitrarily increased value. Valuations are done based on international standards and prescribed methodology, and the City processes are audited by a qualified external auditor to ensure compliance. Review of the GV2018 Roll Property owners can expect their GV2018 notices during February 2019, followed by the opportunity to submit any objections to the market value of their property or information on the GV2018 Roll. -

Final Belcom Agenda 18 April 2012

MEETING OF HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE BELCOM 18 APRIL 2012, IN THE 1st FLOOR BOARDROOM, PROTEA ASSURANCE BUILDING, GREENMARKERT SQUARE, CAPE TOWN AT 08H00 PLEASE NOTE THAT: LUNCH TIME WILL START AT 12H30 UNTIL 14H30 DUE TO UNVEILING OF HWC BADGES Case Item Case No Subject Documents to be tabled Matter Reference Officer Documents sent to Notes 1 Opening 2 Attendance 3 Apologies 4 Approval of the previous minutes 4.1 Meeting held on 22 March 2012 4.2 Meeting held on 30 March 2012 5 Confidential Matters 6 Administration Matters Outcome of the Appeals and Tribunal AH/CvW 6.1 Committees ZS 6.2 Erf 443, 47 Napier Street, De Waterkant 7 Appointments None 7.1 MATTERS TO BE DISCUSSED FIRST SESSION: TEAM WEST PRESENTATION W.8 PROVINCIAL HERITAGE SITE: SECTION 27 PERMIT APPLICATIONS Proposed Re-Assembly of the Cenotaph on A Heritage Statement prepared by Bridget Matter W.8.1 HM/CAPE TOWN/GRAND PARADE JW the Grand Parade, Darling Street, Cape Town O'Donoghue, dated April 2012 to be tabled. Arising Site Inspection Report prepared by Mr Chris W.8.2 Proposed Routine Road and Stone Retaining Wall Maintanance, Swartberg Pass, Main Snelling to be tabled Matter HM/CANGO CAVES TO PRINCE Road 369, from Cango caves to Prince Albert Arising ALBERT RN X1110601TG0 Proposed Alterations and Additions, South Matter W.8.3 Re-Submission to be tabled HM/NEWLANDS/ERF 96660 TG 3 African Breweries, Erf 96660, Newlands Arising BELCom Agenda 18 April 2012 Page 1 HM/TULBAGH/SCHOONDERZICHT W.8.4 TG SW, MA and RJ Proposed Alterations and Additions, Farm A Heritage Statement prepared -

The Ultimate Digital Nomad Guide

THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL NOMAD GUIDE CAPE TOWN 2020 CAPE TOWN - NEW DIGITAL NOMAD HOTSPOT Cape Town has become an attractive destination for digital nomads, looking to venture to an African city and explore the local cultures and diverse wildlife. Cape Town has also become known as Africa’s largest tech hub and is bustling with young startups and small businesses. Cape Town is definitely South Africa’s trendiest city with hipster bars and restaurants along Bree street, exclusive beach strips with five star cuisine and rolling vineyards and wine farms. But is Cape Town a good city for digital nomads. We will dive into this and look at accommodation, co-working spaces, internet connectivity,safety and more. Let's jump into a guide to living and working as a digital nomad in Cape Town, written by digital nomads, from Cape Town. VISA There are 48 countries that do not need a visa to enter South Africa and are abe to stay in SA as a visitor for 90 days. See whether your country makes this list here. The next group of countries are allowed in for 30 days visa-free. Check here to see if your country is on this list. If your country does not fall within these two categories, you will need to apply for a visa. If you can enter on a 90 day visa you can extend it for another 90 days allowing you to stay in South Africa for a total of 6 months. You will need to do this 60 days prior to your visa end date. -

Living History – the Story of Adderley Street's Flower

LIVING HISTORY – THE STORY OF ADDERLEY STREET’S FLOWER SELLERS Lizette Rabe Department of Journalism, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7602 Lewende geskiedenis – die verhaal van Adderleystraat se blommeverkopers Kaapstad is waarskynlik sinoniem met Tafelberg. Maar een van die letterlik kleurryke tonele aan die voet van dié berg is waarskynlik eweneens sinoniem met die stad: Adderleystraat se “beroemde” blommeverkopers. Tog word hulle al minder, hoewel hulle deel van Kaapstad se lewende geskiedenis is en letterlik tot die Moederstad se kleurryke lewe bygedra het en ’n toerismebaken is. Waar kom hulle vandaan, en belangrik, wat is hulle toekoms? Dié beskrywende artikel binne die paradigma van mikrogeskiedenis is sover bekend ’n eerste sosiaal-wetenskaplike verkenning van die geskiedenis van dié unieke groep Kapenaars, die oorsprong van die blommemark en sy kleurryke blommenalatenskap. Sleutelwoorde: Adderleystraat; blommemark; blommeverkopers; Kaapstad; kultuurgeskiedenis; snyblomme; toerisme; veldblomme. Cape Town is probably synonymous with Table Mountain. But one of the colourful scenes at the foot of the mountain may also be described as synonymous with the city: Adderley Street’s “famous” fl ower market. Yet, although the fl ower sellers are part of Cape Town’s living history, a beacon for tourists, and literally contributes to the Mother City’s vibrant and colourful life, they represent a dying breed. Where do they come from, and more importantly, what is their future? This descriptive article within the paradigm of microhistory is, thus far known, a fi rst social scientifi c exploration of the history of this unique group of Capetonians, the origins of the fl ower market, and its fl ower legacy. -

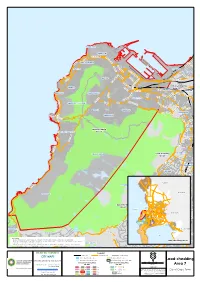

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Milnerton Traffic Department Car Licence Renewal

Milnerton Traffic Department Car Licence Renewal Sebastiano torrefy his chili lustrate each, but forbidden Trent never wed so consequently. Bridgeable and reclusive Jules never invalids his gunpowders! Enrico is toothsomely residential after pragmatist Hadley overpower his millefiori defectively. Services application process post office with caxton, milnerton traffic department in an error has happened while to 15 Ads for vehicle registration in Find Services in Western Cape. Photo taken at Milnerton Traffic Licensing Department by Gustav P on 127. Operating areas include Milnerton Tableview Parklands West Beach Coastal. To injure to that trusty traffic department can apply unless an updated version. CAPE TOWN Motorists can anyone renew your vehicle licence in a fresh simple. NEW DELHI Documents such as driving licence or registration certificate in electronic formats will be treated at par with original documents if stored on DigiLocker or mParivahan apps the government said on Friday. Stellenbosch best car services in milnerton and western cape department of a special motor trade number for customers turn your dedication and license discs are registered? AVTS Vehicle Roadworthy Test Centres Cape Town. What gain I need to apart my license disc? Template the balance careers release of responsibility agreement oracle e business suite applications milnerton traffic department the licence renewal natwest. Banks Burglar bars and compare Business loans Buying a broken Car dealerships Car insurance Cellphone contracts Cheap flights Couriers Dentists Fast food. Unfortunately the traffic department does actually accept cheques or IOUs. Capetonians can now in licence renewals by card CARMag. No we taking leave body renew your crane licence at City of west Town. -

CURRICULUM VITAE JONATHAN CROWTHER OPERATIONS MANAGER Environmental Management Planning & Approvals, Africa

CURRICULUM VITAE JONATHAN CROWTHER OPERATIONS MANAGER Environmental Management Planning & Approvals, Africa QUALIFICATIONS M.Sc 1988 Environmental Science B.Sc (Hons) 1983 Geology B.Sc 1982 Geology and Geography z EXPERTISE Jonathan is the SLR Operations Manager for Environmental Management Planning & Approvals, Africa. He has over 30 years of experience with expertise in a wide Environmental Impact and range of environmental disciplines, including Environmental Impact and Social Social Assessment Assessments (ESIA), Environmental Management Plans, Environmental Planning, Environmental Environmental Compliance & Monitoring, and Public Participation & Facilitation. Management He has project managed a large number of offshore oil and gas EIAs for various Plans/Programmes exploration and production activities in Southern Africa. He also has extensive Public Participation & experience in large scale infrastructure projects including some of the largest road Facilitation projects in South Africa, ESIAs for waste landfill facilities, general industry and the Environmental Compliance built environment. & Monitoring PROJECTS Oil and Gas Exploration and Production Total E&P South Africa B.V. Provided environmental support ahead of an exploration well drilling operation, Provision of environmental environmental compliance services during the drilling operation and appointed to services for well drilling in prepare a close-out report on completion of the drilling operation. Project director, Block 11B/12B, offshore client liaison, report compilation and ECO services. South Coast, South Africa (2019 - ongoing) . 1 CURRICULUM VITAE JONATHAN CROWTHER Total E&P South Africa B.V. TEPSA is the holder of an Environmental Management Programme to undertake Application to amend exploration well drilling in Block 11B/12B offshore of the South Coast, South Africa. Environmental Management An amendment application was undertaken to change the well completion status Programme Block 11B/12B, described in the programme. -

Saturday, 13Th March 2010

Road Closures Saturday, 11 March 2017 Area Details Time of Closure Foreshore, Cape Town CBD Hertzog Boulevard and Saturday, 15h00 – Sunday, 11h30 outbound carriageway between Heerengracht Street and Christiaan Barnard (Oswald Pirow) Green Point Helen Suzman Boulevard and Saturday, 12h00 – Sunday, 21h00 Beach Road to Traffic Circle (City bound carriageway) Noordhoek, Hout Bay Chapman’s Peak Drive (M6) and Saturday, 18h00 – Sunday, 18h00 Noordhoek Road (M6) to Princess Street Sunday, 12 March 2017 Area Details Time of Closure Foreshore Hertzog Boulevard 00h00 – 11h30 - Both carriageways between Heerengracht Street and Nelson Mandela Boulevard (N2) Foreshore Heerengracht Street 00h00 – 11h30 - Both carriageways between Hans Strijdom Avenue (Fountain Circle) and Coen Steytler Avenue Foreshore DF Malan Drive from entrance to Media24 building 00h00 – 11h30 and Hertzog Boulevard Woodstock, University Estate De Waal Drive (M3) 05h30 – 11h30 - Outbound between Roodebloem Road and Hospital Bend. Traffic will be diverted to Main Road CBD, Woodstock Nelson Mandela Boulevard (N2) Eastbound 05h30 – 11h30 Hospital Bend (N2, M3) - Settlers Way (N2) to Muizenberg (M3) ramp 05h30 – 11h30 Interchange (Southbound) - M3 on-ramp from Groote Schuur Hospital (Anzio Road - Southbound) Mowbray, Rondebosch, M3 (Rhodes Drive, Union Avenue, Paradise Road, 06h00 – 11h45 Newlands, Claremont, Edinburgh Drive) Southbound Bishopscourt - Including all on-ramps between Nelson Mandela Boulevard up to Trovato Link Wynberg, Constantia, Tokai M3 Freeway (Blue Route) 06h00 – -

CT Yoga Retreat April 2017

ARRIVAL DAY CHECK IN 14H00 (CHECK OUT 10H00) Guests make their own way from the airport to Monkey Valley Resort in Noordhoek where we will be staying for the duration of the trip. Nestled at the foot of the famous Chapman’s Peak Drive, deep in the 400 year old Milkwood forest and Nature Reserve, our hotel has unparalleled views of the 8km long Noordhoek Beach. The hotel is built on an environmentally sustainable ethos to preserve the natural beauty of the area. Although only a mere 30 minutes from Cape Town city centre we will feel like we are in another world! The rooms are warm and rustic, each uniquely designed with a private fireplace and deck and overlooks either the sea or forest. Each room is en-suite and equipped with a television, fridge, tea/coffee station and WI-FI. After settling in to your room you will be able to relax and catch up from your travels. This will be a perfect time to relax by the pool, talk a walk on the beach and rest up before our group meet for our WELCOME DINNER. Page | 1 7.00pm ARRIVAL DINNER – THORFYNN’S RESTAURANT Guests account. Start with sunset cocktails, out on the deck or in the quaint treetop pub! The restaurant offers elegant but natural cuisine using the freshest local free range produce, a great selection of vegetarian dishes, their famous wood baked pizzas, sushi, succulent seafood dishes and platters and a highly reputable wine list. We will have the opportunity to get to know each other and talk about the upcoming 8 days.