Enchanting Witch Hazels Enchanting Witch Hazels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flower Colors of Hardy Hybrid Rhododendrons

ARNOLDIA A continuation of the , BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 9 JULY 1, 1949 NUMBERS 7-8 FLOWER COLORS OF HARDY HYBRID RHODODENDRONS hybrid broad-leaved evergreen rhododendrons are most conspicuous dur- THEing early June. If grown in fertile, acid soil, mulched properly and pruned properly (see ARNOLDIA, Vol. 8, No. 8, September, 1948) they should pro- duce a bright display of flowers annually. The collection in the Arnold Arbore- tum is over fifty years old and has been added to continually from year to year. Rhododendron enthusiasts are continually studying this collection, noting the differences between the many varieties now being grown. Not all that are avail- able in the eastern United States nurseries are here, but many are, and it serves a valuable purpose, at the same time making a splendid display. It is most difficult to properly identify the many hardy rhododendron hybrids. The species are of course keyed out in standard botanical keys, but there is little easily available information about the identification of hybrids grown in the East. There are no colored pictures or paintings sufficiently accurate for this purpose, nor are there suitable descriptions of the flower colors. Articles for popular peri- odicals are numerous, but color descriptions in these are entirely too general. The term "crimson flowers" may cover a dozen or more varieties, each one of which does differ slightly from the others. Size of truss, of flower, markings on corolla and even the color of the stamens and pistils are all aides in identification. Consequently, we have started an attempt at the proper description of hybrid varieties, growing in our collection, by the careful comparison of colors of the flowers as they bloomed this year, with the colors of the Royal Horticultural Society’s Colour Chart. -

Super Cyclamen a Full Line-Up!

Cyclamen by Size MICRO MINI INTERMEDIATE STANDARD JUMBO Micro Verano Rembrandt XL Mammoth Mini Winter Allure Picasso Super Cyclamen A Full Line-up! Seed of the cyclamen series listed in this brochure are available through Sakata for shipment effective January 2015. In addition, the following series are available via drop ship directly from The Netherlands. Please contact Sakata or your preferred dealer for more information. Sakata Ornamentals Carino I mini Original I standard P.O. Box 880 Compact I mini Macro I standard Morgan Hill, CA 95038 DaVinci I mini Petticoat I mini 408.778.7758 Michelangelo I mini Merengue I intermediate www.sakataornamentals.com Jive I mini 10.2014 Super Cyclamen A Full Line-up! Sakata Seed America is proud to offer a complete line of innovative cyclamen series bred by the leading cyclamen experts at Schoneveld Breeding. From mini to jumbo, we’re delivering quality you can count on… Uniformity Rounded plant habit Central blooming Thick flower stems Abundant buds & blooms Long shelf life Enjoy! Our full line-up of cyclamen delivers long-lasting beauty indoors and out. Micro Verano F1 Cyclamen Micro I P F1 Cyclamen Mini I B P • Genetically compact Dark Salmon Pink Dark Violet Deep Dark Violet • More tolerant of higher temperatures • Perfect for 2-inch pot production • Well-known for fast and very uniform flowering • A great item for special marketing programs • Excellent for landscape use MINIMUM GERM: 85% MINIMUM GERM: 85% SEED FORM: Raw SEED FORM: Raw TOTAL CROP TIME: 27 – 28 Weeks TOTAL CROP TIME: 25 – 27 Weeks -

Print This Article

International Journal of Phytomedicine 6 (2014) 177-181 http://www.arjournals.org/index.php/ijpm/index Original Research Article ISSN: 0975-0185 The effect of Cyclamen coum extract on pyocyanin production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Zahra Ahmadbeigi1*, Azra Saboora1, Ahya Abdi-Ali1 *Corresponding author: Abs tract Researches have shown that some plants possess antimicrobial activity and the ability to overcome Zahra Ahmadbeigi drug-resistant pathogens. Their frequent used in treatment of microbial infections has been led to isolation of the active compounds and evaluation of their antimicrobial properties. Cyclamen coum Miller is one of these plants with a secondary metabolite called saponin which has antimicrobial 1Department of Biology, Faculty of activity. Pyocyanin is one of the virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic Science, University of Alzahra, Tehran pathogen, causing lung diseases. The present study indicates the effect of cyclamen saponin 1993893973, Iran extracts on pyocyanin production by P. aeruginosa. We prepared three different types of plant extracts (ethanolic, aqueous and butanolic) from tuber of C. coum. The effect of 0, 10 and 20 mg of cyclamen saponin were tested by agar disk diffusion technique. Pyocyanin purification was done from microbial broth culture and the extracted pyocyanin was measured by spectrophotometric method. Results showed that the production of pyocyanin was remarkably reduced by ethanolic extract of saponin. In addition increased saponin concentration led to further decrease in pyocyanin content. Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Cyclamen coum; Pyocyanin; Antimicrobial activity es Bacterial cells communicate with each other through producing Introduction signaling factors named inducers. When bacterial cell density increases, the inducers bind to the receptors and alter the Extensive In vitro studies on plants used in traditional medicine expression of certain genes. -

2020 Appendixes

Forcing Bulbs to Bloom in Winter A wonderful way to bring a bit of spring into your home In the dead of winter, spring blooming bulbs are especially welcome in the house. They fill any room with lively color (and maybe scent) and remind us that spring is just around the corner. Narcissus Forcing Narcissus in Water: • Place bulbs in a shallow bowl filled with gravel; mound gravel around sides of bulbs. • Add water so it barely touches bulbs. • Place bowl in a cool, dark location. • When roots start to grow, keep water below bulbs. • When top growth grows, move bowl to bright light but out of direct sunlight. • Bulbs bloom in about 6 weeks. Narcissus also grow well in vases with just water. Bulbs should be firm, without soft spots or scars. Bulbs with two "noses", or tips, will produce two stems. Forcing Narcissus in Soil: • Choose a wide pot about 6” deep with drainage holes in the bottom. Fill the pot loosely with potting mix. Set bulbs side by side, close but not touching, pointed end up, so that the tips are even with the pot rim. Do not press the bulbs into the mix. It should be loose to allow the roots to grow through it easily. Cover with additional potting mix, so the noses are barely covered. • Water thoroughly and empty drainage tray. • Daffodils need a cold treatment for 8-10 weeks. If you pre-chilled bulbs, you can skip this step. Move pot to a dark, cool (40-45°F) location such as a basement, unheated garage or refrigerator. -

Hardy Cyclamen. Thomas Hood Wrote a Poem Which Neatly Sums up How Most of Us Feel About This Time of the Year

Hardy Cyclamen. Thomas Hood wrote a poem which neatly sums up how most of us feel about this time of the year. It starts: ‘No sun - no moon! No morn -no noon! No dawn- no dusk! No proper time of day!’ The poem finishes: ‘No shade, no shine, no butterflies, no bees No fruits, no flowers, no leaves, no birds, November!’ Of course we have fruits and flowers at the moment and leaves too, they are hanging on late this year, but the glorious fire of Autumn leaves collapses into a soggy mush this month and many of the flowers that are left are the brave and pathetic last ditch attempts of summer flowering plants. Cyclamen hederifolium though, is still looking good after making its first appearance as early as August. This plant used to be called Cyclamen neapolitanum but is no longer known by that name. It is a little gem with ivy shaped leaves, hence the name ‘hederifolium’ which means ivy-leafed. The heart-shaped leaves differ enormously in shape and size; most of them are exquisitely marbled in grey or silver. Sometimes the leaves appear before the flowers, sometimes the flowers appear first, and sometimes they come together. The flowers have five reflex petals and they come in varying shades of pink with a deep v-shaped magenta blotch at the base. There is enormous variation in the shape and size of the flowers. Some of mine are as big as the florist’s cyclamen, Cyclamen persicum which of course is not hardy. The lovely white form is equally desirable. -

Review of Species Selected from the Analysis of 2004 EC Annual Report

Review of species selected from the Analysis of 2005 EC Annual Report to CITES (Version edited for public release) Prepared for the European Commission Directorate General E - Environment ENV.E.2. – Development and Environment by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre May, 2008 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK ABOUT UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the world‘s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision- makers recognize the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre‘s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP, the European Commission or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Cyclamen Purpurascens Mill.) TUBERS

Advanced technologies 7(1) (2018) 05-10 BIOACTIVE COMPOUNDS AND MINERAL COMPOSITON OF THE AQUEOUS EXTRACT FROM WILD CYCLAMEN (Cyclamen purpurascens Mill.) TUBERS * Ljiljana Stanojević , Dragan Cvetković, Saša Savić, Sanja Petrović, Milorad Cakić (ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER) UDC 582.689.1:66.061.34:543.5 University of Niš, Faculty of Technology, Leskovac, Serbia doi:10.5937/savteh1801005S Wild cyclamen tubers (Cyclamen purpurascens Mill.) (Kukavica mountain, south- east Serbia) was used as an extraction material in this study. The aqueous extract has been obtained by reflux extraction at the boiling temperature with hydromodu- lus 1:20 m/v during 180 minutes. The identification of bioactive components in the Keywords: Wild cyclamen tubers, Aque- extract was performed by using UHPLC–DAD–HESI–MS analysis. The concentra- ous extract, UHPLC–DAD–HESI–MS tions of macro- and microelements in the extract were determined by Inductively analysis, Micro- and Macroelements. Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES). Isocyclamin and des- glucocyclamin I were identified in the obtained extract. Potassium was in the highest concentration - 10241.65 mg/kg of the plant material, while zinc was present in the highest concentration (11.57 mg/kg of plant material) among heavy metals. Pre- sented results have shown that the obtained extract from wild cyclamen tubers is a potential source of triterpenoide saponin components isocyclamin and desglucocy- clamin I, as well as macro- and microelements. Introduction Wild cyclamen (Cyclamen purpurascens Mill.; Syn. Cy- Besides the main bioactive components identification, clamen europaeum L.), or purple cyclamen, is a species macro- and microelements in the aqueous extract of wild in the Cyclamen genus of the Primulaceae family [1]. -

Cyclamen Persicum

The Canadian Botanical Association Bulletin Bulletin de l'Association Botanique du Canada Vol. 53 Number 1, March/mars 2020 Highlights in this issue: 2020 CBA Annual Top Ornamental Plants: Meeting Cyclamen page 4 page 5 In this issue: President’s Message 3 2020 CBA Conference Update 4 Top Canadian Ornamental Plants. 25. Cyclamen 5 The Canadian Botanical Association Bulletin Bulletin de l’Association Botanique du Canada The CBA Bulletin is issued three times a year (March, Septem- Le Bulletin de I’ABC paraît trois fois par année, normalement en ber and December) and is freely available on the CBA website. mars, septembre et décembre. Il est envoyé à tous les membres Hardcopy subscriptions are available for a fee. de I’ABC. Information for Contributors Soumission de textes All members are welcome to submit texts in the form of pa- Tous les membres de I’Association sont invités à envoyer des pers, reviews, comments, essays, requests, or anything related textes de toute natureconcernant la botanique et les botanistes to botany or botanists. For detailed directives on text submis- (articles, revues de publication, commentaires,requêtes, essais, sion please contact the Editor (see below). For general informa- etc.). Tous les supports de texte sont acceptés. Pour des ren- tion about the CBA, go to the web site: www.cba-abc.ca seignements détaillés sur la soumission de textes, veuillez con- sulter le rédacteur (voir ci-dessous). Infos générales sur I’ABC à Editor l’url suivant: www.cba-abc.ca Dr. Tyler Smith K.W. Neatby Building, 960 Carling Avenue Rédacteur Ottawa ON, K1A 0C6 Dr. -

Plant Perennials This Fall to Enjoy Throughout the Year Conditions Are Perfect for Planting Perenni - Esque Perennials Like Foxglove, Delphinium, Next

Locally owned since 1958! Volume 26 , No. 3 News, Advice & Special Offers for Bay Area Gardeners FALL 2013 Ligularia Cotinus Bush Dahlias Black Leafed Dahlias Helenium Euphorbia Coreopsis Plant perennials this fall to enjoy throughout the year Conditions are perfect for planting perenni - esque perennials like Foxglove, Delphinium, next. Many perennials are deer resistant (see als in fall, since the soil is still warm from the Dianthus, Clivia, Echium and Columbine steal our list on page 7) and some, over time, summer sun and the winter rains are just the show. In the summertime, Blue-eyed need to be divided (which is nifty because around the corner. In our mild climate, Grass, Lavender, Penstemon, Marguerite and you’ll end up with more plants than you delightful perennials can thrive and bloom Shasta Daisies, Fuchsia, Begonia, Pelargonium started with). throughout the gardening year. and Salvia shout bold summer color across the garden. Whatever your perennial plans, visit Sloat Fall is when Aster, Anemone, Lantana, Garden Center this fall to get your fall, win - Gaillardia, Echinacea and Rudbeckia are hap - Perennials are herbaceous or evergreen ter, spring or summer perennial garden start - pily flowering away. Then winter brings magi - plants that live more than two years. Some ed. We carry a perennial plant, for every one, cal Hellebores, Cyclamen, Primrose and die to the ground at the end of each grow - in every season. See you in the stores! Euphorbia. Once spring rolls around, fairy- ing season, then re-appear at the start of the Inside: 18 favorite Perennials, new Amaryllis, Deer resistant plants, fall clean up and Bromeliads Visit our stores: Nine Locations in San Francisco, Marin and Contra Costa Richmond District Marina District San Rafael Kentfield Garden Design Department 3rd Avenue between 3237 Pierce Street 1580 Lincoln Ave. -

PDF Document

Cyclamen Notes by Wilhelm (Bill) Bischoff Flowers of Atlantis? Page 2 Cyclamen Blooming Times Page 4 Cyclamen Species, Subspecies, Page 5 Forma, & Varieties in Alphabetical Order Cyclamen Descriptions Page 6 (photos referenced are not included) Wilhelm (Bill) Bischoff is available for lectures & garden tours for Cyclamen & Hardy Orchids 604-589-6134 wbischoff @ shaw.ca The Flowers of Atlantis? By Wilhelm (Bill) Bischoff / member BC Council of Garden Clubs If you can accept that the island called Santorini in the central Mediterranean, also known as Thira / Tera, is the original Island of Atlantis; if you also can agree that this Island had a terrific volcanic explosion more than 3,000 years ago, than I can share with you an equally fantastic botanical story with you. That today’s Thira is the remnant of an exploded volcano is quite evident when one looks at a map of this region of the Mediterranean. Located as part of the Aegean Islands, just north of Crete, it shows the unmistakable shape of a water filled volcanic caldera with a center-cone island. Scientists have identified volcanic ash taken from the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, close to the Lebanese coast, as originating from Thira. The time frame of some 3300 years ago also coincides with the beginning of a rather tumultuous time in this part of the ancient world, the end of the “Bronze Age”. The possible cause of that could well have been a natural disaster, in the very heart of the ancient world as we know it. Now that I have your attention and possibly have whetted your curiosity, let me introduce you to one of the small wonders of this very ancient world, the beautiful Cyclamen, all 22 species of them. -

Landscaping Without Harmful Invasive Plants

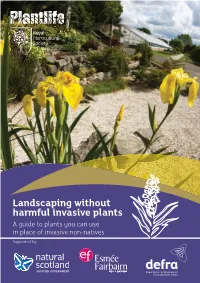

Landscaping without harmful invasive plants A guide to plants you can use in place of invasive non-natives Supported by: This guide, produced by the wild plant conservation Landscaping charity Plantlife and the Royal Horticultural Society, can help you choose plants that are without less likely to cause problems to the environment harmful should they escape from your planting area. Even the most careful land managers cannot invasive ensure that their plants do not escape and plants establish in nearby habitats (as berries and seeds may be carried away by birds or the wind), so we hope you will fi nd this helpful. A few popular landscaping plants can cause problems for you / your clients and the environment. These are known as invasive non-native plants. Although they comprise a small Under the Wildlife and Countryside minority of the 70,000 or so plant varieties available, the Act, it is an offence to plant, or cause to damage they can do is extensive and may be irreversible. grow in the wild, a number of invasive ©Trevor Renals ©Trevor non-native plants. Government also has powers to ban the sale of invasive Some invasive non-native plants might be plants. At the time of producing this straightforward for you (or your clients) to keep in booklet there were no sales bans, but check if you can tend to the planted area often, but it is worth checking on the websites An unsuspecting sheep fl ounders in a in the wider countryside, where such management river. Invasive Floating Pennywort can below to fi nd the latest legislation is not feasible, these plants can establish and cause cause water to appear as solid ground. -

RHS Gardening in a Changing Climate Report

Gardening in a Changing Climate Acknowledgements The RHS and University of Reading would like to acknowledge the support provided by Innovate UK through the short Knowledge Transfer Partnership KTP 1000769 from November 2012 to September 2013. The RHS is grateful to the Trustees of Spencer Horticultural Trust, who supported the project to revise the Gardening in the Global Greenhouse report. The RHS would also like to thank: The authors of the 2002 report, Richard Bisgrove and Professor Paul Hadley, for building the foundations for this updated report. The contributors of this report: Dr John David (RHS), Dr Ross Cameron (University of Sheffield), Dr Alastair Culham (University of Reading), Kathy Maskell (Walker Institute, University of Reading) and Dr Claudia Bernardini (KTP Research Associate). Dr Mark McCarthy (Met Office) and Professor Tim Sparks (Coventry University) for their expert consultation on the climate projections and phenology chapters, respectively. This document is available to download as a free PDF at: Gardening in a www.rhs.org.uk/climate-change Citation Changing Climate Webster E, Cameron RWF and Culham A (2017) Gardening in a Changing Climate, Royal Horticultural Society, UK. Eleanor Webster, About the authors Ross Cameron and Dr Eleanor Webster is a Climate Scientist at the Royal Horticultural Alastair Culham Society Dr Ross Cameron is a Senior Lecturer in Landscape Management, Ecology & Design at the University of Sheffield Dr Alastair Culham is an Associate Professor of Botany at the University of Reading Gardening in a Changing Climate RHS 2 3 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 3.4 The UK’s variable weather and its implications for projections of future climate .......................................................