Poems by Jidi Majia Jidi Majia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No.9 Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter June 1990

[Last updated: 28 April 1992] ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- No.9 Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter June 1990 This NEWSLETTER is edited by Gehan Wijeyewardene and published in the Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies; printed at Central Printery; the masthead is by Susan Wigham of Graphic Design (all of The Australian National University ).The logo is from a water colour , 'Tai women fishing' by Kang Huo Material in this NEWSLETTER may be freely reproduced with due acknowledgement. Correspondence is welcome and contributions will be given sympathetic consideration. (All correspondence to The Editor, Department of Anthropology, RSPacS, ANU, Box 4 GPO, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia.) Number Nine June 1990 ISSN 1032-500X The International Conference on Thai Studies, Kunming 1990 There was some question, in the post Tien An Men period, as to whether the conference would proceed. In January over forty members of Thammasart University faculty issued an open letter to the organizers, which in part read, A meeting in China at present would mean a tacit acceptance of the measures taken by the state, unless there will be an open critical review. Many north American colleagues privately expressed similar views. This Newsletter has made its views on Tien An Men quite clear, and we can sympathize with the position taken by our colleagues. Nevertheless, there seems to be some selectivity of outrage, when no word of protest was heard from some quarters about the continuing support given by the Chinese government to the murderous Khmer Rouge. This does not apply to the Thai academic community, sections of which were in the vanguard of the movement to reconsider Thai government policy on this issue. -

Research Degree and Professional Doctorate Students Output (July

RESEARCH DEGREE AND PROFESSIONAL DOCTORATE STUDENTS’ RESEARCH OUTPUT (July 2013 – June 2014) This report summarizes the research outputs of our research degree and professional doctorate students, and serves to recognize their hard work and perseverance. It also acts as a link between the University and the community, as it demonstrates the excellent research results that can benefit the development of the region. Chow Yei Ching School of Graduate Studies February 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OF RESEARCH OUTPUT PRODUCED BY PHD STUDENTS IN 2013-2014 ............................... IV SUMMARY OF RESEARCH OUTPUT PRODUCED BY MPHIL STUDENTS IN 2013-2014 ............................. V SUMMARY OF RESEARCH OUTPUT PRODUCED BY PROFESSIONAL DOCTORATE STUDENTS IN 2013- 2014 ............................................................................................................................................ VI SECTION A: PUBLICATIONS OF PHD STUDENTS ................................................................................... 7 COLLEGE OF BUSINESS .................................................................................................................................... 7 DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTANCY ......................................................................................................................... 7 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE ....................................................................................................... 7 DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS .......................................................................................................... -

China's NOTES from the EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who with National Culture

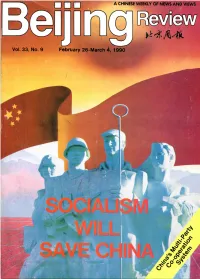

—Inspired by the Lei Feng* spirit of serving the people, primary school pupils of Harbin City often do public cleanups on their Sunday holidays despite severe winter temperature below zero 20°C. Photo by Men Suxian * Lei Feng was a squad leader of a Shenyang unit of the People's Liberation Army who died on August 15, 1962 while on duty. His practice of wholeheartedly serving the people in his ordinary post has become an example for all Chinese people, especially youfhs. Beijing««v!r VOL. 33, NO. 9 FEB. 26-MAR. 4, 1990 Carrying Forward the Cultural Heritage CONTENTS • In a January 10 speech. CPC Politburo member Li Ruihuan stressed the importance of promoting China's NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who With national culture. Li said this will help strengthen the coun• Sanctions? try's sense of national identity, create the wherewithal to better resist foreign pressures, and reinforce national cohe• EVENTS/TRENDS 5 8 sion (p. 19). Hong Kong Basic Law Finalized Economic Zones Vital to China NPC to Meet in March Sanctions Will Get Nowhere Minister Stresses Inter-Ethnic Unity • Some Western politicians, in defiance of the reahties and Dalai's Threat Seen as Senseless the interests of both China and their own countries, are still Farmers Pin Hopes On Scientific demanding economic sanctions against China. They ignore Farming the fact that sanctions hurt their own interests as well as 194 AIDS Cases Discovered in China's (p. 4). China INTERNATIONAL Upholding the Five Principles of Socialism Will Save China Peaceful Coexistence 9 Mandela's Release: A Wise Step o This is the first instalment of a six-part series contributed Forward 13 by a Chinese student studying in the United States. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

World Bank Document

Poverty Alleviation and Agriculture Development Demonstration in Poor Areas Project sichuan Procurement Plan Public Disclosure Authorized I. General 1. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan [Original: May 13, 2015: 1stRevision: May 11, 2018, 2nd Revision: November 27, 2018] 2. Date of General Procurement Notice: November 23, 2015 3. Period covered by this procurement plan: 2018 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: Procurement Method Prior Review Threshold Comments US$ 1. ICB and LIB (Goods) Above US$ 10million All 2. NCB (Goods) Above US$ 2million All 3. ICB (Works) Above US$ 40 million All 4. NCB (Works) Above US$ 10 million All Public Disclosure Authorized 5. (Non-Consultant Services) Above US$ 2million All [Add other methods if necessary] 2. Prequalification. Bidders for _Not applicable_ shall be prequalified in accordance with the provisions of paragraphs 2.9 and 2.10 of the Guidelines. 3. Proposed Procedures for CDD Components (as per paragraph. 3.17 of the Guidelines: [Yes, in procurement manual] 4. Reference to (if any) Project Operational/Procurement Manual: Yes Public Disclosure Authorized 5. Any Other Special Procurement Arrangements: no 6. Summary of the Procurement Packages planned: [List the Packages which require Bank’s prior review first and then the other packages] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ref. No. Description Estimated Packages Domestic Review Comments Preference Cost by Bank (yes/no) US$ million (Prior / Post) Summary of the ICB (Works) Summary of the ICB (Goods) Summary of the NCB (Works) Summary of the NCB (Goods) Summary of 2.2 23 No Post the Shopping (Works) Summary of 0.062 1 No Post the Shopping (Goods) Summary of the ICB (Non- Consultant Services) Summary of the NCB (Non- Consultant Services) Summary of the Shopping (Non- Consultant Services) III. -

Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau

IPP740 REV World Bank-financed Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Ethnic Minority Development Plan of the Yunnan Highway Assets Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau July 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized EMDP of the Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Summary of the EMDP A. Introduction 1. According to the Feasibility Study Report and RF, the Project involves neither land acquisition nor house demolition, and involves temporary land occupation only. This report aims to strengthen the development of ethnic minorities in the project area, and includes mitigation and benefit enhancing measures, and funding sources. The project area involves a number of ethnic minorities, including Yi, Hani and Lisu. B. Socioeconomic profile of ethnic minorities 2. Poverty and income: The Project involves 16 cities/prefectures in Yunnan Province. In 2013, there were 6.61 million poor population in Yunnan Province, which accounting for 17.54% of total population. In 2013, the per capita net income of rural residents in Yunnan Province was 6,141 yuan. 3. Gender Heads of households are usually men, reflecting the superior status of men. Both men and women do farm work, where men usually do more physically demanding farm work, such as fertilization, cultivation, pesticide application, watering, harvesting and transport, while women usually do housework or less physically demanding farm work, such as washing clothes, cooking, taking care of old people and children, feeding livestock, and field management. In Lijiang and Dali, Bai and Naxi women also do physically demanding labor, which is related to ethnic customs. Means of production are usually purchased by men, while daily necessities usually by women. -

Trilingual Literacy for Ethnic Groups in China a Case Study of Hani People in Yuanyang County of Yunnan

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 4, No. 4; December 2011 Trilingual Literacy for Ethnic Groups in China A case study of Hani People in Yuanyang County of Yunnan Yuanbing Duan School of Arts and Science, Yunnan Radio and TV University, Kunming, 650223, China Tel: 86-871-588-6817 E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 23, 2011 Accepted: June 13, 2011 Published: December 1, 2011 doi:10.5539/elt.v4n4p274 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n4p274 Abstract This paper examines the current trilingual literacy situation of Hani People in Yuanyang County of Yunnan, China, with significance of finding out specific problems which influence the trilingual education greatly. It also reports on the effects of training for trilingual teachers, ways of improving learner’s motivation and updating the trilingual education materials. Lastly, several possible solutions are provided for successful minority education. Keywords: Trilingual literacy, Trilingual education, Minority education 1. Introduction This paper will discuss one part of school literacy in China, to be specific, how do ethnic groups start learning English, their difficulties and problems in current situation, and suggested solutions are provided for guiding students’ literacy success. With the reform and open policy carried out in 1978, education in China has gained its growing concern; more and more people have had the consciousness of being literate. However, literacy means two different levels in countryside and in cities. In rural countryside, to complete middle school education owns the opportunity of attaining stable job to meet local demand, education at this level simply means having the ability to read and write; while in the big cities, pursuing higher degree, university education or post graduate education, highlight the functional meaning of literacy; being ‘knowledgeable’ at this high level requires the ability to read between lines and write academically. -

The History of the History of the Yi, Part II

MODERNHarrell, Li CHINA/ HISTORY / JULY OF 2003THE YI, PART II REVIEW10.1177/0097700403253359 Review Essay The History of the History of the Yi, Part II STEVAN HARRELL LI YONGXIANG University of Washington MINORITY ETHNIC CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE 1980S AND 1990S The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is, according to its constitution, “a unified country of diverse nationalities” (tongyide duominzu guojia; see Wang Guodong, 1982: 9). The degree to which this admirable political ideal has actually been respected has varied throughout the history of the PRC: taken seriously in the early and mid-1950s, it was systematically ignored dur- ing the twenty years of High Socialism from the late 1950s to the early 1980s and then revived again with the Opening and Reform policies of the past two decades (Heberer, 1989: 23-29). The presence of minority “autonomous” ter- ritories, preferential policies in school admissions, and birth quotas (Sautman, 1998) and the extraordinary emphasis on developing “socialist” versions of minority visual and performing arts (Litzinger, 2000; Schein, 2000; Oakes, 1998) all testify to serious attention to multinationalism in the cultural and administrative realms, even if minority culture is promoted in a homogenized socialist version and even if everybody knows that “autono- mous” territories are far less autonomous, for example, than an American state or a Swiss canton. But although the party state now preaches multinationalism and allows limited expression of ethnonational autonomy, it also preaches and promotes progress—and thus runs straight into a paradox: progress is defined in objectivist, modernist terms, which relegate minority cultures to a more MODERN CHINA, Vol. -

Hnewo Teyy – Posvátná Kniha Nuosuů

Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Karlovy v Praze HNEWO TEYY – POSVÁTNÁ KNIHA NUOSUŮ Vypracovala: Nina Vozková, obor SIN Vedoucí práce: Doc. PhDr. Olga Lomová, CSc. Nina Vozková Hnewo Teyy – posvátná kniha Nuosuů Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a že seznam použité literatury je kompletní. V Praze 28.4. 2006 Nina Vozková 1 Nina Vozková Hnewo Teyy – posvátná kniha Nuosuů Mé díky patří především vedoucí práce Doc. PhDr. Olze Lomové, která mi poskytla plnou podporu při výběru tématu a posléze se mnou pečlivě každou část práce konzultovala. Děkuji profesoru Luo Qingchunovi za jeho neúnavnou ochotu a pomoc při překladu, mému bratru za pomoc s ediční úpravou, sestře a paní Miroslavě Jirkové za korekturu. Děkuji také Hlávkově nadaci, která přispěla finančním příspěvkem na mou první cestu do Číny v letech 1998 až 1999. Rodiče mě trpělivě podporovali po celou dobu studia a i jim jsem za všechnu pomoc ze srdce vděčná. 2 Nina Vozková Hnewo Teyy – posvátná kniha Nuosuů OBSAH ENGLISH ABSTRACT ................................................................................................5 I. ÚVOD.........................................................................................................................6 Transkripce............................................................................................................................ 8 Literatura a další zdroje......................................................................................................... 8 II. KLASIFIKACE NÁRODNOSTÍ PO VZNIKU ČLR............................................11 -

The Position of Tusi Within Area of Liangshan

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Ústav Dálného východu Diplomová práce Bc. Jan Karlach Pomocí barbarů ovládat barbary: Postavení tusi v oblasti Liangshanu By Barbarians Control Barbarians: The Position of Tusi within Area of Liangshan konzultant: Praha 2014 Mgr. Jakub Hrubý, Ph.D. 1 Za vedení práce děkuji Mgr. Jakubu Maršálkovi, Ph.D. Za konstruktivní připomínky, neocenitelnou pomoc v podobě mnoha desítek hodin strávených nad textem a za všeobecnou výraznou podporu děkuji konzultantovi této práce, Mgr. Jakubu Hrubému, Ph.D., bez něhož by tato práce nemohla ve své stávající podobě vzniknout. Projektu Erasmus Mundus MULTI a s ním spojeným semestrálním pobytem na Hong Kong Polytechnic University vděčím za rychlý a snadný přístup k pramenům a literatuře, stejně jako za možnost načerpat energii v inspirativním a motivujícím akademickém prostředí. Sunim Choi, Ph.D., Mgr. Nině Kopp a Mgr. Ondřeji Klimešovi, Ph.D. vděčím za pomoc při hledání a určování vhodných pramenů a literatury, jakožto i za tematickou inspiraci a neutuchající podporu. RNDr. Ivaně Frolíkové pak za převedení ručních náčrtků map do vektorové elektronické podoby. Poděkování si zaslouží rovněž Devon Williams, M.A., ač permanentně vzdálen na druhé straně zeměkoule, nikdy ani na vteřinu neváhal podat pomocnou ruku, stejně jako Marc Todd, B.A. V neposlední řadě musím poděkovat Zheng Jianzhongovi 鄭建中 za pomoc při luštění mnohdy nečitelných znaků z moderních přetisků původních místních kronik. 2 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně, že jsem řádně citoval všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Hongkongu dne 1.1.2014 Bc. -

Poetry Planetariat No 5. PDF File

Poetry Planetariat IssueIssue 5, 2, Summer Fall 2019 2020 IstanbulIstanbul / / Medellin Medellin D. Payne PoetsPoets of ofthe the World World UniteUnite Against Against Injustice Injustice Copyright 2020 World Poetry Movement Publisher: World Poetry Movement www.wpm2011.org [email protected] Editor: Ataol Behramoğlu [email protected]/[email protected] Associate Editor: Pelin Batu [email protected] Editorial Board: Mohammed Al-Nabhan (Kuwait), Ayo Ayoola-Amalae (Nigeria), Francis Combes (France), Jack Hirschman (USA), Jidi Majia (China), Fernando Rendón (Colombia), Rati Saxena (India), Keshab Sigdel (Nepal) Paintings by Emmanuel Adekeye/Dorothy Payne Layout by Gülizar Ç. Çetinkaya [email protected] Adress: Tekin Publishing House Ankara Cad.Konak Han, No:15 Cağaloğlu-İstanbul/Turkey Tel:+(0212)527 69 69 Faks:+(0212)511 11 12 www.tekinyayinevi.com e-mail:[email protected] ISSN XXXXX Poetry Planetariat is published four times a year in Istanbul by the World Poetry Movement in cooperation with Ataol Behramoğlu-Pelin Batu and Tekin Publishing House CONTENTS WE NEED TO BREATHE/ATAOL BEHRAMOĞLU A LETTER TO MAYOR LONDON BREED AND SAN FRANCISCO BOARD OF SUPERVISORS(SARAH MENEFEE/ JACK HIRSCHMAN/ MARIA CRISTINA GUTIERREZ/ JESSICA G. AGUALLO-HURTADO) AN INTRODUCTION TO THE POETRY OF THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN POETS/JACK HIRSCHMAN I CAN’T BREATHE- MAKING HUMANITYDOOMED/ AYO AYOOLA-AMALE POETRY OPAL PALMER-ADISA/SAMAR ALİ/AYO AYOOLA-AMALE/ CHARLES BLACKWELL/ JAME CAG- NEY/ MAKETA SMITH –GROVES/ VİNCENT KOBELT/ DEVORAH MAJOR/ TONGO EISEN-MARTIN/ NGWATILO MAWIYOO/ ZOLANİ MKİVA/ NANCY MOREJON/ CHRİSTOPHER OKEMWA/ ODOH DİEGO OKONYONDO/GREG POND/ WOLE SOYİNKA/AXARO W THANİSEB/ MİCHAEL WARR/ ASHRAF ABAOUL YAZİD IN MEMORIAM LANGSTON HUGHES LEOPOLD SENGHOR JAMES BALDWIN MAYA ANGELOU AMIRI BARAKA WE NEED TO BREATHE/ATAOL BEHRAMOĞLU Choking is stay oxygen-free. -

Online Supplementary Document Song Et Al

Online Supplementary Document Song et al. Causes of death in children younger than five years in China in 2015: an updated analysis J Glob Health 2016;6:020802 Table S1. Description of the sources of mortality data in China National Mortality Surveillance System Before 2013, the Chinese CRVS included two systems: the vital registration system of the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) (the former Ministry of Health) and the sample-based disease surveillance points (DSP) system of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The vital registration system was established in 1973 and started to collect data of vital events. By 2012, this system covered around 230 million people in 22 provinces, helping to provide valuable information on both mortality and COD patterns, although the data were not truly representative for the whole China [55]. DSP was established in 1978 to collect data on individual births, deaths and 35 notifiable infectious diseases in surveillance areas [56]. By 2004, there were 161 sites included in the surveillance system, covering 73 million persons in 31 provinces. The sites were selected from different areas based on a multistage cluster sampling method, leading to a very good national representativeness of the DSP [57, 58]. From 2013, the above two systems were merged together to generate a new “National Mortality Surveillance System” (NMSS), which currently covers 605 surveillance points in 31 provinces and 24% of the whole Chinese population. The selection of surveillance points was based on a national multistage cluster sampling method, after stratifying for different socioeconomic status to ensure the representativeness [17, 58].