Text (Redacted)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICC Playing Handbook 2011-12

playing handbook The official handbook for international cricket players, officials, administrators and media 2011–2012 www.icc-cricket.com ICC PLAYING HANDBOOK 2011 - 2012 The official handbook for international cricket players, officials, administrators and media SECTION 01 ICC Structure and Contacts 02 ICC Member Countries 03 Standard Test Match Playing Conditions 04 Standard One-Day International Match Playing Conditions 05 Standard Twenty20 International Match Playing Conditions 06 Duckworth-Lewis 07 Women’s Test Match Playing Conditions 08 Women’s One-Day International Playing Conditions 09 Women’s Twenty20 Playing Conditions 10 Standard ICC Intercontinental Cup and ICC Intercontinental Shield Playing Conditions 11 ICC 50-Over League Playing Conditions 12 Pepsi ICC World Cricket League Standard Playing Conditions 13 ICC Code of Conduct for Players and Player Support Personnel 14 ICC Code of Conduct for Umpires 15 ICC Anti-Racism Code for Players and Player Support Personnel 16 ICC Anti-Doping Code 17 ICC Anti-Corruption Code for Players and Player Support Personnel 18 ICC Regulations for the Review of Bowlers Reported with Suspected Illegal Bowling Actions 19 Clothing and Equipment Rules and Regulations 20 Other ICC Regulations All information valid at 20 September 2011 0.1 0.2 INTRODUCTION Welcome to the 2011-12 edition of the ICC Playing Handbook. This handbook draws together the main regulations that govern international cricket including the playing conditions for men’s and women’s Test Match, One-Day and Twenty20 cricket, as well as Development events, such as the Pepsi ICC World Cricket League and the ICC Intercontinental Cup, and also the Code of Conduct which regulates the behaviour of players and officials. -

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Committee on Foreign Affairs

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Committee on Foreign Affairs Brussels, 27 July 2004 REPORT OF AD HOC DELEGATION VISITS TO KASHMIR (8-11 DECEMBER 2003 AND 20-24 JUNE 2004) Introduction As part of the European Parliament's contribution to helping shape EU policy on the Kashmir issue, the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights, Common Security and Defence Policy decided to send a delegation to both parts of Kashmir, and to the respective national capitals of Pakistan and India. The delegation's objective was to meet with a wide spectrum of political and public opinion, to learn their views on current developments and hopes for the future, and to see the situation on the ground at first- hand. For timetabling and logistical reasons, it was decided that the visit to the two sides (Islamabad and Pakistan-administered Kashmir (known as Azaad Jammu and Kashmir - AJK - on the Pakistan side) -, and to New Delhi and Jammu and Kashmir - Indian- administered Kashmir, would have to take place separately. The first visit took place from 8-11 December 2003; the second, originally planned for the spring of 2004 was delayed because of the elections which were unexpectedly called in India, and finally took place from 20-25 June 2004. It was stressed throughout the preparatory phases that the two delegation visits should be undertaken by the same Members - which, with one exception, was the case - and that the two visits should aim to follow similar programmes in order to ensure continuity and for a balanced comparison to be made. The delegation was led by John Walls Cushnahan, and in December 2003 included Bob van den Bos, David Bowe, Glyn Ford, Jas Gawronski, Reinhold Messner and Luisa Morgantini. -

Islamophobia and Religious Intolerance: Threats to Global Peace and Harmonious Co-Existence

Qudus International Journal of Islamic Studies (QIJIS) Volume 8, Number 2, 2020 DOI : 10.21043/qijis.v8i2.6811 ISLAMOPHOBIA AND RELIGIOUS INTOLERANCE: THREATS TO GLOBAL PEACE AND HARMONIOUS CO-EXISTENCE Kazeem Oluwaseun DAUDA National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN), Jabi-Abuja, Nigeria Consultant, FARKAZ Technologies & Education Consulting Int’l, Ijebu-Ode [email protected] Abstract Recent events show that there are heightened fear, hostilities, prejudices and discriminations associated with religion in virtually every part of the world. It becomes almost impossible to watch news daily without scenes of religious intolerance and violence with dire consequences for societal peace. This paper examines the trends, causes and implications of Islamophobia and religious intolerance for global peace and harmonious co-existence. It relies on content analysis of secondary sources of data. It notes that fear and hatred associated with Islām and persecution of Muslims is the fallout of religious intolerance as reflected in most melee and growingverbal attacks, trends anti-Muslim of far-right hatred,or right-wing racism, extremists xenophobia,. It revealsanti-Sharī’ah that Islamophobia policies, high-profile and religious terrorist intolerance attacks, have and loss of lives, wanton destruction of property, violation led to proliferation of attacks on Muslims, incessant of Muslims’ fundamental rights and freedom, rising fear of insecurity, and distrust between Muslims and QIJIS, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2020 257 Kazeem Oluwaseun DAUDA The paper concludes that escalating Islamophobic attacks and religious intolerance globally hadnon-Muslims. constituted a serious threat to world peace and harmonious co-existence. Relevant resolutions in curbing rising trends of Islamophobia and religious intolerance are suggested. -

C.A. 767 2014.Pdf

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction) Present: MR. JUSTICE MUSHIR ALAM MR. JUSTICE QAZI FAEZ ISA MR. JUSTICE SARDAR TARIQ MASOOD Civil Appeal No. 767 of 2014 and C. M. A. No. 565-K/2013 (On appeal against the judgment dated 10.07.2013 passed by the High Court of Sindh, Karachi, in C.P.No. D-2643/2012) Sindh Revenue Board through its Chairman, Government of Sindh and another…………………….Appellants Versus The Civil Aviation Authority of Pakistan through its Airport Manager, Jinnah International Airport, Karachi…………………………Respondent For Appellant No. 1: Mr. Farooq H. Naek, Senior ASC For Appellant No. 2: Mr. Khalid Javed Khan, ASC Mr. Fouzi Zafar, ASC Raja Abdul Ghafoor, AOR For the Respondents: Syed Naveed Amjad Andrabi, ASC On behalf of Federation: Mr. Muhammad Waqar Rana, Additional Attorney General On behalf of Govt. of Sindh: Mr. Sabtain Mehmood, Additional Advocate General Dates of Hearing: April 6, 12 and 13, 2017 JUDGMENT Qazi Faez Isa, J: The High Court of Sindh at Karachi allowed a petition filed by the Civil Aviation Authority (“CAA”) under Article 199 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (“the Constitution”). The CAA, which was established under the Pakistan Civil Aviation Authority Ordinance, 1982 (“the CAA Ordinance”), had filed the said petition challenging the imposition of sales tax on services levied upon it under the Sindh Sales Tax on C. A. No. 767/2014. 2 Services Act, 2011 (hereinafter “the Act”) and the Sindh Sales Tax on Services Rules, 2011 (hereinafter “the Rules”). 2. The learned Division Bench of the High Court allowed the petition filed by CAA and declared that CAA was, “not liable to pay the tax under the Sindh Sales Tax on Services Act, 2011”, consequently, all demands made, proceedings initiated, orders passed or notices issued to CAA under the Act and the Rules were quashed and set aside. -

March 20, 2008 the Free-Content News Source That You Can Write! Page 1

March 20, 2008 The free-content news source that you can write! Page 1 Top Stories Top Stories Wikipedia Current Events Zenit rocket launches that "removing Saddam Hussein such autonomy...which could be DirecTV-11 satellite from power was the right decision seen as a move towards A Ukranian-built Zenit-3SL rocket — and this is a fight America can independence." The Foreign has had a and must win." The speech Ministry also linked the events in successful lift-off marked five years since the start Tibet with the declaration of from a Norwegian of the Iraq War. independence by Kosovo, launch platform to showing a growing movement of carry a groups seeking independence. communications •The Parliament of Pakistan elects satellite for DirecTV Wikinews interviews author Fahmida Mirza as its first female into orbit. and filmmaker John Gaspard speaker. Launching at Author and filmmaker John 22:47:59 (UTC) yesterday Gaspard spoke with Wikinews on evening, the mission marked the his three low budget feature films Hubble detects methane on 13th orbital launch of 2008 and and books. He told us how he distant planet the 25th commercial launch to be was able to make his latest NASA's Hubble Space Telescope conducted by the international movie, Grown Men, for under has detected methane in the Sea Launch consortium. $13,000 and how his popular atmosphere of a planet 63 light- book, Digital Filmmaking 101, years away, marking the first Three of Serbia's neighbors came to be. He even had a few discovery of an organic compound recognize Kosovo tips for the amateur filmmakers on a planet outside our Solar Croatia, Bulgaria and Hungary, all reading this. -

The Senate of Pakistan Debates Contents

THE SENATE OF PAKISTAN DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT Tuesday, November 13, 2012 (87th Session) Volume XI No. 04 (Nos.01-10) CONTENTS Pages 1. Recitation from the Holy Quran. .………....…….. 1 2. Questions and Answers …………………………. 2-24 3. Leave of Absence………………………………... 25 4. Presentation of Report of the Standing Committee on Defence and Defence Production……………... 26 5. Privilege Motion Misconduct of I.G. Punjab...................................... 27-28 6. Legislative Business The Intellectual Property Organization of Pakistan Bill, 2012………………………………………… 29 7. Point of Order Misappropriation in Senate Housing Society and other Societies…………………….................. 30-36 8. Resolution Felicitation to the Hindu Community of Pakistan on Diwali ……………………………………….. 37-44 Printed and Published by the Senate Secretariat, Islamabad. Volume XI SP.XI(04)/2012 No.04 15 SENATE OF PAKISTAN SENATE DEBATES Tuesday, November 13, 2012 The Senate of Pakistan met in the Senate Hall (Parliament House) Islamabad, at forty five minutes past four in the evening with Mr. Chairman (Syed Nayyar Hussain Bokhari) in the Chair. ---------------- Recitation from the Holy Quran ‰ ‰ ‰ ª‰ ª ª ‰‰ ‚‚ÂÂş ‰ - ‰ ‰ ‰ ª⁄ª ªªÂ‚ ‚ „ ‚ÂÂ!ª‹ #≈‹ ªč&' ª&‚‚‚ „‚ ‚ ‚ ‚‚ ‚ , ‚ ,!(ª)ª'* ª+'' , , . ("45) 6783 9!7 23 !()'* +'' / 0 # , ., , , . 1 1 C ( :;" 9 <5=!>25 9?2 +@AB, ,,, D " +@! , H =: '* EF " B#$&) +!7?G''* , , , , , /" 2! , , E;"M)''* , , / K "L1 1 1 OOO IG + % -

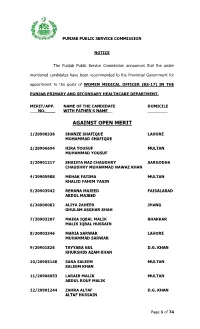

Against Open Merit

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION NOTICE The Punjab Public Service Commission announces that the under mentioned candidates have been recommended to the Provincial Government for appointment to the posts of WOMEN MEDICAL OFFICER (BS-17) IN THE PUNJAB PRIMARY AND SECONDARY HEALTHCARE DEPARTMENT. MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.____ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ AGAINST OPEN MERIT 1/20900338 SHANZE SHAFIQUE LAHORE MOHAMMAD SHAFIQUE 2/20906694 HIRA YOUSUF MULTAN MUHAMMAD YOUSUF 3/20901217 SHAISTA NAZ CHAUDHRY SARGODHA CHAUDHRY MUHAMMAD NAWAZ KHAN 4/20905988 MEHAK FATIMA MULTAN KHALID FAHIM YASIN 5/20903942 REHANA MAJEED FAISALABAD ABDUL MAJEED 6/20900082 ALIYA ZAHEER JHANG GHULAM ASGHAR SHAH 7/20903207 MAIRA IQBAL MALIK BHAKKAR MALIK IQBAL HUSSAIN 8/20903346 MARIA SARWAR LAHORE MUHAMMAD SARWAR 9/20901826 TAYYABA GUL D.G. KHAN KHURSHID AZAM KHAN 10/20905148 SARA SALEEM MULTAN SALEEM KHAN 11/20906053 LARAIB MALIK MULTAN ABDUL ROUF MALIK 12/20901244 ZAHRA ALTAF D.G. KHAN ALTAF HUSSAIN Page 1 of 74 From Pre-page 1315 posts of Women Medical Officer (BS-17) in the Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare Department MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.__ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ 13/20903132 ZAHRA MUSHTAQ RAWALPINDI MUHAMMAD MUSHTAQ AHMAD 14/20901604 MARIA FATIMA OKARA QURBAN ALI 15/20901854 HAFIZA AMMARA SIDDIQI FAISALABAD MUHAMMAD SIDDIQUE 16/20904115 QURAT-UL-AIN SARWAR LAHORE MANZOOR SARWAR CHAUDHARY 17/20901733 AALIA BASHIR D.G. KHAN SHEIKH DAUD ALI 18/20905234 FARVA KOMAL M. GARH GHULAM HAIDER KHAN 19/20901333 SADIA MALIK SARGODHA GHULAM MUHAMMAD 20/20904405 ZARA MAHMOOD RAWALPINDI MAHMOOD AKHTER 21/20900565 MARIA IRSHAD HAFIZABAD IRSHAD ULLAH 22/20902101 FARYAL ASIF SARGODHA ASIF ILYAS 23/20901525 MAHAM FATIMA M. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

P14 3 Layout 1

THURSDAY, AUGUST 10, 2017 SPORTS Ranatunga urges ICC to probe Sri Lanka chief COLOMBO: Former skipper Arjuna office at SLC, as well as at the Asian Cricket Ranatunga has blamed Sri Lanka’s string of Council and ICC. “I deny any involvement humiliating defeats on the country’s cricket personally, directly or indirectly with gam- chief and demanded his investigation by ing business,” Sumathipala told AFP. the International Cricket Council. In what could be the opening shots of a new bid to ‘THEY MESSED UP EVERYTHING’ head Sri Lanka Cricket, Ranatunga, 53, told He also slammed Ranatunga, Sri Lanka’s AFP there was no “proper discipline” in the minister of petroleum, for accusing President national team which has had a horror run Maithripala Sirisena’s government of failing of results. to protect the game. “If he wants to criticise The team lost by an innings and 53 runs the government, he must first resign,” in the second Test against India on Sunday, Sumathipala, said adding that allegations are after being crushed in the first match by frequently made against the board when the 304 runs. They are now fighting to avoid a national team performs badly. whitewash in the three-Test series. Sri “Every time the game is affected at the Lanka also suffered an early exit from the middle, Sri Lanka cricketers are not per- Champions Trophy, and lost a one-day forming to the expectation, we hear this series at home to bottom ranked kind of noise coming from the same quar- Zimbabwe last month. Ranatunga accused ter,” Sumathipala said. -

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths. -

Conflict Between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict

Conflict between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict Conflict between India and Pakistan Peter Lyon Conflict in Afghanistan Ludwig W. Adamec and Frank A. Clements Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia John B. Allcock, Marko Milivojevic, and John J. Horton, editors Conflict in Korea James E. Hoare and Susan Pares Conflict in Northern Ireland Sydney Elliott and W. D. Flackes Conflict between India and Pakistan An Encyclopedia Peter Lyon Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright 2008 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lyon, Peter, 1934– Conflict between India and Pakistan : an encyclopedia / Peter Lyon. p. cm. — (Roots of modern conflict) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57607-712-2 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-57607-713-9 (ebook) 1. India—Foreign relations—Pakistan—Encyclopedias. 2. Pakistan-Foreign relations— India—Encyclopedias. 3. India—Politics and government—Encyclopedias. 4. Pakistan— Politics and government—Encyclopedias. I. Title. DS450.P18L86 2008 954.04-dc22 2008022193 12 11 10 9 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Production Editor: Anna A. Moore Production Manager: Don Schmidt Media Editor: Jason Kniser Media Resources Manager: Caroline Price File Management Coordinator: Paula Gerard This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

Pakistani Politics 1243 Pakistani Politics the Lesson of Gramdan 1244 ERSONALITIES Count in the Politics of Every Country

(Established January 1949) September 28, 1957 Volume IX—No, 39 Price 50 Naye Paise EDITORIALS Pakistani Politics 1243 Pakistani Politics The Lesson of Gramdan 1244 ERSONALITIES count in the politics of every country. But in WEEKLY NOTES P Pakistan, politics seem to centre mainly around personalities. Thin Kandla Nearing Capacity- explains the frequent changes in party tactics and the policies of parties. Reassessment Necessary In such circumstances, as is only to be expected, political stability eludes —Pibul Goes — Welcome the country. It is tempting to draw a parallel between Pakistan and Rapprochement — P r o- Prance. There are some similarities in the underlying conditions in blem of Housing—Scarcity Pakistan and Indonesia. But there are limits beyond which such com of Material — U P's Tax parisons are misleading. Even as President Soekarno experiments with on Large Holdings Bank "guided democracy", President Iskander Mirza talks about "controlled Rate Change and India- democracy". But the Indonesian President's policy is based on an ideal Production of Radio Re whereas the Pakistani President's interference with the affairs of the ceivers 1247 State is solely justified on considerations of that country's integrity. LETTER TO THE EDITOR That also is the main, if not the only, binding force among parties and Chair-borne Critics 1250 politicians in Pakistan. A CALCUTTA DIARY Yet, experience and developing events make it increasingly evident Not by the Police Alone 1251 that Pakistan's march to progress cannot be ensured on such negative foundations as the country's integrity, annexation of Kashmir and the FROM THE LONDON END ever-present problem of maintaining a precarious balance between the Seven Per Cent and the country's two wings.