E Cacy and Safety of Empagli Ozin Continuation in Patients with Type

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on Pulmonary Hypertension 2015 (TF08) - Task Force Members and Additional Contributors

Guidelines on Pulmonary Hypertension 2015 (TF08) - Task Force Members and Additional Contributors For ESC Guidelines: The report below lists declarations of interest as reported to the ESC by the experts covering the period of the Guidelines production, from Task Force creation to publication. Expert Type of Relationship with Industry Beghetti Maurice A - Direct Personal payment: Speaker fees, Honoraria, Consultancy, Advisory Board fees, Investigator, Committee Member, etc. - Novartis : Pulmonary hypertension imatinib (2012) - Pfizer : Pulmonary hypertension sildenafil (2012-2013) - Bayer Schering Pharma : Pulmonary hypertension riociguat (2012-2013-2014-2015) - Eli Lilly : Pulmonary hypertension tadalafil (2012-2013-2014-2015) - Actelion : Pulmonary hypertension, Tracleer, Macitentan, Selexipag (2012-2013-2014-2015) - GlaxoSmithKline : pulmonary hypertension Ambrisentan (2012-2015) - Novartis : Pulmonary hypertension riociguat (2013) - GlaxoSmithKline : ambrisentan (2014) D - Research funding (departmental or institutional). - Actelion : no relation to a specific product (2012-2013) - Bayer Schering Pharma : no relation to a specific product (2014-2015) Galie Nazzareno A - Direct Personal payment: Speaker fees, Honoraria, Consultancy, Advisory Board fees, Investigator, Committee Member, etc. - Eli Lilly : pulmonary hypertension (2012-2013) - Novartis : pulmonary hypertension (2012-2013) - Pfizer : pulmonary hypertension (2012-2013) - Actelion : pulmonary hypertension (2012-2013) - GlaxoSmithKline : pulmonary hypertension (2012-2013) -

Future Diagnostic & Therapeutic Targets in Cardiorenal Syndromes

Future Diagnostic & Therapeutic Targets in Cardiorenal Syndromes (Biomarkers, advanced monitoring, advanced imaging, novel therapies) EDGAR V. LERMA, MD Clinical Professor of Medicine Secon of Nephrology UIC/ Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn, IL May 27, 2017 Disclosure of Interests • Honoraria: UpToDate, McGraw-Hill Publishing, Elsevier Publishing, Springer Publishing, Wolters-Kluwer Publishing, ACP Smart Medicine, Emedicine • Editorial Boards: American Journal of Kidney Diseases, ASN Kidney News, Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Clinical Reviews in Bone and Mineral Metabolism, International Urology and Nephrology, Journal of Clinical Lipidology, Prescribers Letter, Renal and Urology News, Reviews in Endocrinology and Metabolic Disorders, Seminars in Dialysis • Speaker/ Advisory Board: Astute Medical, Mallinckrodt, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, ZS Pharma KDIGO Controversies Conference on Heart Failure in CKD May 25-28, 2017 | Athens, Greece Disclosure of ABIM Service: Edgar V. Lerma, M.D. ▪ I am a current member of the ABIM Self-Assessment Committee. ▪ To protect the integrity of certification, ABIM enforces strict confidentiality and ownership of exam content. ▪ My participation in this CME activity is allowed under ABIM policy and is subject to the following: • As a member of an ABIM test committee, I agreed to keep exam information confidential, as it is owned exclusively by ABIM. • As is true for any ABIM candidate who has taken an exam for certification, I have signed the Pledge of Honesty in which I have agreed -

Classification Decisions Taken by the Harmonized System Committee from the 47Th to 60Th Sessions (2011

CLASSIFICATION DECISIONS TAKEN BY THE HARMONIZED SYSTEM COMMITTEE FROM THE 47TH TO 60TH SESSIONS (2011 - 2018) WORLD CUSTOMS ORGANIZATION Rue du Marché 30 B-1210 Brussels Belgium November 2011 Copyright © 2011 World Customs Organization. All rights reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning translation, reproduction and adaptation rights should be addressed to [email protected]. D/2011/0448/25 The following list contains the classification decisions (other than those subject to a reservation) taken by the Harmonized System Committee ( 47th Session – March 2011) on specific products, together with their related Harmonized System code numbers and, in certain cases, the classification rationale. Advice Parties seeking to import or export merchandise covered by a decision are advised to verify the implementation of the decision by the importing or exporting country, as the case may be. HS codes Classification No Product description Classification considered rationale 1. Preparation, in the form of a powder, consisting of 92 % sugar, 6 % 2106.90 GRIs 1 and 6 black currant powder, anticaking agent, citric acid and black currant flavouring, put up for retail sale in 32-gram sachets, intended to be consumed as a beverage after mixing with hot water. 2. Vanutide cridificar (INN List 100). 3002.20 3. Certain INN products. Chapters 28, 29 (See “INN List 101” at the end of this publication.) and 30 4. Certain INN products. Chapters 13, 29 (See “INN List 102” at the end of this publication.) and 30 5. Certain INN products. Chapters 28, 29, (See “INN List 103” at the end of this publication.) 30, 35 and 39 6. Re-classification of INN products. -

The Evolution of Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction Pharmacotherapy: What Do We Have and Where Are We Going?

Pharmacology & Therapeutics 178 (2017) 67–82 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pharmacology & Therapeutics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pharmthera Associate editor: M. Curtis The evolution of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction pharmacotherapy: What do we have and where are we going? Ahmed Selim, Ronald Zolty, Yiannis S. Chatzizisis ⁎ Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA article info abstract Available online 21 March 2017 Cardiovascular diseases represent a leading cause of mortality and increased healthcare expenditure worldwide. Heart failure, which simply describes an inability of the heart to meet the body's needs, is the end point for many Keywords: other cardiovascular conditions. The last three decades have witnessed significant efforts aiming at the discovery Heart failure of treatments to improve the survival and quality of life of patients with heart failure; many were successful, Reduced ejection fraction while others failed. Given that most of the successes in treating heart failure were achieved in patients with re- Pharmacotherapy duced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF), we constructed this review to look at the recent evolution of Novel drugs HFrEF pharmacotherapy. We also explore some of the ongoing clinical trials for new drugs, and investigate poten- tial treatment targets and pathways that might play a role in treating HFrEF in the future. © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Contents 1. Introduction.............................................. -

Involvement of Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate-Dependent Protein Kinase I in Renal Antifibrotic Effects of Serelaxin

fphar-07-00195 July 9, 2016 Time: 13:1 # 1 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Frontiers - Publisher Connector ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 12 July 2016 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00195 Involvement of Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate-Dependent Protein Kinase I in Renal Antifibrotic Effects of Serelaxin Veronika Wetzl1,2†, Elisabeth Schinner1†, Frieder Kees1, Franz Hofmann3, Lothar Faerber1,2 and Jens Schlossmann1* 1 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany, 2 Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nuremberg, Germany, 3 Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany Introduction: Kidney fibrosis has shown to be ameliorated through the involvement of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and its dependent protein kinase I (cGKI). Serelaxin, the recombinant form of human relaxin-II, increases cGMP levels and has Edited by: Enno Klussmann, shown beneficial effects on kidney function in acute heart failure patients. Antifibrotic Max Delbrüeck Center for Molecular properties of serelaxin are supposed to be mediated via relaxin family peptide receptor Medicine, Germany 1 and subsequently enhanced nitric oxide/ cGMP to inhibit transforming growth factor- Reviewed by: Friedrich Wilhelm Herberg, b (TGF-b) signaling. This study examines the involvement of cGKI in the antifibrotic University of Kassel, Germany signaling of serelaxin. Choel Kim, Baylor College of Medicine, USA Methods and Results: Kidney fibrosis was induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction in *Correspondence: wildtype (WT) and cGKI knock-out (KO) mice. After 7 days, renal antifibrotic effects Jens Schlossmann of serelaxin were assessed. Serelaxin treatment for 7 days significantly increased [email protected] regensburg.de cGMP in the kidney of WT and cGKI-KO. -

Jimmunol.1800856.Full.Pdf

Healthy Donors Exhibit a CD4 T Cell Repertoire Specific to the Immunogenic Human Hormone H2-Relaxin before Injection This information is current as of September 26, 2021. Aurélien Azam, Yann Gallais, Sergio Mallart, Stephane Illiano, Olivier Duclos, Catherine Prades and Bernard Maillère J Immunol published online 17 May 2019 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2019/05/14/jimmun Downloaded from ol.1800856 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2019/05/14/jimmunol.180085 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Material 6.DCSupplemental Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists by guest on September 26, 2021 • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2019 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Published May 17, 2019, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1800856 The Journal of Immunology Healthy Donors Exhibit a CD4 T Cell Repertoire Specific to the Immunogenic Human Hormone H2-Relaxin before Injection Aure´lien Azam,*,† Yann Gallais,† Sergio Mallart,‡ Stephane Illiano,x Olivier Duclos,‡ Catherine Prades,* and Bernard Maille`re† H2-relaxin (RLN2) is a two-chain peptide hormone structurally related to insulin with a therapeutic potential in multiple indica- tions. -

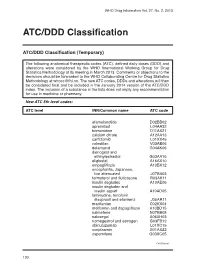

ATC/DDD Classification

WHO Drug Information Vol. 27, No. 2, 2013 ATC/DDD Classification ATC/DDD Classification (Temporary) The following anatomical therapeutic codes (ATC), defined daily doses (DDD) and alterations were considered by the WHO International Working Group for Drug Statistics Methodology at its meeting in March 2013. Comments or objections to the decisions should be forwarded to the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology at [email protected]. The new ATC codes, DDDs and alterations will then be considered final and be included in the January 2014 version of the ATC/DDD index. The inclusion of a substance in the lists does not imply any recommendation for use in medicine or pharmacy. New ATC 5th level codes: ATC level INN/Common name ATC code afamelanotide D02BB02 apremilast L04AA32 brimonidine D11AX21 calcium citrate A12AA13 carfilzomib L01XX45 colestilan V03AE06 delamanid G04AK06 dienogest and ethinylestradiol G03AA16 eliglustat A16AX10 empagliflozin A10BX12 encephalitis, Japanese, live attenuated J07BA03 formoterol and fluticasone R03AK11 insulin degludec A10AE06 insulin degludec and insulin aspart A10AD05 lamivudine, tenofovir disoproxil and efavirenz J05AR11 macitentan C02KX04 metformin and dapagliflozin A10BD15 nalmefene N07BB05 naloxegol A06AH03 nomegestrol and estrogen G03FB12 obinutuzumab L01XC15 ocriplasmin S01AX22 ospemifene G03XC05 Continued/ 130 WHO Drug Information Vol. 27, No. 2, 2013 ATC/DDD Classification ATC level INN/Common name ATC code pomalidomide L04AX06 serelaxin C01DX21 strontium ranelate and colecalciferol -

WO 2016/044447 Al 24 March 2016 (24.03.2016) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/044447 Al 24 March 2016 (24.03.2016) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: ue, Belmont, Massachusetts 02478 (US). IYER, Karthik; C07D 401/14 (2006.01) A61K 31/505 (2006.01) 30 Cambridge Park Drive, Apt. #6121, Cambridge, Mas C07D 413/14 (2006.01) A61K 31/519 (2006.01) sachusetts 02140 (US). IYENGAR, Rajesh R.; 23 Strat C07D 403/04 (2006.01) A61K 31/53 (2006.01) ford Road, West Newton, Massachusetts 02465 (US). IM, C07D 403/14 (2006.01) A61P 9/00 (2006.01) G-Yoon Jamie; 93 1 Massachusetts Avenue, Apt. 604, C07D 417/14 (2006.01) A61P 25/00 (2006.01) Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). C07D 487/04 (2006.01) A61P 15/00 (2006.01) (74) Agent: FREDERICKS, Kellie S.; Heslin Rothenberg Far C07D 491/10 (2006.01) A61P 3/00 (2006.01) ley & Mesiti P.C., 5 Columbia Circle, Albany, New York C07D 495/04 (2006.01) 12203 (US). (21) International Application Number: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every PCT/US20 15/050468 kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, (22) International Filing Date: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, 116 September 2015 (16.09.201 5) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (25) Filing Language: English HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (26) Publication Language: English KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (30) Priority Data: PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, 62/05 1,557 17 September 2014 (17.09.2014) US SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 62/204,710 13 August 2015 (13.08.2015) US TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Pharmacotherapies in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.13604 Pharmacotherapies in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Nischit Baral 1 , Swotantra Gautam 2 , Saroj A. Yadav 3 , Sangeeta Poudel 4 , Govinda Adhikari 5 , Rohit Rauniyar 5 , Pramod Savarapu 5 , Anjan Katel 6 , Anish C. Paudel 7 , Prem R. Parajuli 7 1. Internal Medicine, McLaren Health Care, Flint/Michigan State University, Michigan, USA 2. General Medicine, B. P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, NPL 3. General Medicine, Patan Academy of Health Sciences, Kathmandu, NPL 4. General Medicine, KIST Medical College/Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, NPL 5. Internal Medicine, McLaren Flint/Michigan State University, Flint, USA 6. Internal Medicine, Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences, Dhulikhel, NPL 7. Internal Medicine, Reading Hospital Tower Health, Reading, USA Corresponding author: Nischit Baral, [email protected] Abstract Background: Heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) causes significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. It is a growing problem in the developed world, especially, in the aging population. There is a paucity of data on the treatment of patients with HFpEF. We aimed to identify pharmacotherapies that improve peak oxygen consumption (peak VO2), cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalizations in patients with HFpEF. Methods: We conducted a systematic literature search for English studies in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google scholar. We searched databases using terms relating to or describing HFpEF, stage C HFpEF, and diastolic HF and included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs). RevMan 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020, London, UK) was used for data analysis, and two independent investigators performed literature retrieval and data-extraction. -

Reasanz; INN Serelaxin

22 May 2014 EMA/303748/2014 Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Assessment report Reasanz International non-proprietary name: serelaxin Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/002817 Note Assessment report as adopted by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. 30 Churchill Place ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 5EU ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 3660 6000 Facsimile +44 (0)20 3660 5520 Send a question via our website www.ema.europa.eu/contact An agency of the European Union Product information Name of the medicinal product: Reasanz Applicant: Novartis Europharm Ltd Wimblehurst Road Horsham West Sussex RH12 5AB UNITED KINGDOM Active substance: serelaxin International Nonproprietary Name/Common serelaxin Name: Pharmaco-therapeutic group (ATC Code): C01DX21 Therapeutic indication (as applied for) : Reasanz is indicated for the treatment of acute heart failure and to reduce mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Pharmaceutical form: Concentrate for solution for infusion Strengths: 1 mg/ml Route of administration: Intravenous use Packaging: vial (glass) Package size: 1 vial Assessment report EMA/303748/2014 Page 2/112 Table of contents 1. Background information on the procedure ............................................ 10 1.1. Submission of the dossier .................................................................................... 10 1.2. Steps taken for the assessment of the product ....................................................... 11 Steps taken for the re-examination procedure -

Relaxin As a Therapeutic Target for the Cardiovascular Complications of Diabetes

fphar-09-00501 May 10, 2018 Time: 18:15 # 1 MINI REVIEW published: 15 May 2018 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00501 Relaxin as a Therapeutic Target for the Cardiovascular Complications of Diabetes Hooi Hooi Ng1,2,3*, Chen Huei Leo1,4, Laura J. Parry1 and Rebecca H. Ritchie2,5 1 School of BioSciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2 Heart Failure Pharmacology, Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 3 Department of Human and Molecular Genetics, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, Miami, FL, United States, 4 Science and Math Cluster, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore, Singapore, 5 Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Cardiovascular complications are the major cause of mortality in patients with diabetes. This is closely associated with both macrovascular and microvascular complications of diabetes, which lead to organ injuries in diabetic patients. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated the beneficial effects of relaxin treatment for protection of the vasculature, with evidence of antioxidant and anti-remodeling actions. Relaxin enhances nitric oxide, prostacyclin and endothelium-derived hyperpolarization (EDH)- Edited by: Issy Laher, type-mediated relaxation in various vascular beds. These effects of relaxin on the University of British Columbia, systemic vasculature, coupled with its cardiac actions, reduce pulmonary capillary United States wedge pressure and pulmonary artery pressure. This results in an overall decrease in Reviewed by: Gaetano Santulli, systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance in heart failure patients. The anti-fibrotic Columbia University, United States actions of relaxin are well established, a desirable property in the context of diabetes. -

Pharmacokinetics of Serelaxin in Patients With

British Journal of Clinical DOI:10.1111/bcp.12572 Pharmacology Correspondence Dr Marion Dahlke, Novartis Pharma AG, Pharmacokinetics of serelaxin CH-4056 Basel, Switzerland. Tel.: +41 79 5590130 Fax: +41 61 3246623 in patients with hepatic E-mail: [email protected] ----------------------------------------------------------------------- impairment: a single-dose, Keywords cardiovascular disease, healthy subjects, hepatic, pharmacokinetics, therapeutics open-label, parallel ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Received 4 September 2014 group study Accepted 9 December 2014 Zhanna Kobalava,1 Svetlana Villevalde,1 Yulia Kotovskaya,1 Accepted Article 2 3 4 Published Online Holger Hinrichsen, Marc Petersen-Sylla, Andreas Zaehringer, 16 December 2014 Yinuo Pang,5 Iris Rajman,4 Jasna Canadi,4 Marion Dahlke,4 Peter Lloyd6 & Atef Halabi3 1Peoples Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia, 2Gastroenterologisch-Hepatologisches Zentrum Kiel, Kiel, 3Clinical Research Services, Kiel, Germany, 4Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Basel, Switzerland, 5Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Cambridge, MA, USA and 6KinDyn Consulting Ltd, Horsham, UK WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT • Data available from completed clinical studies of serelaxin, a recombinant form of AIMS human relaxin-2 currently in clinical Serelaxin is a recombinant form of human relaxin-2 in development for treatment of development for the treatment of acute acute heart failure. This study aimed to evaluate the pharmacokinetics