Narratives of Blindness in the Long Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins

早稲田大学国際教養学部 Waseda Global Forum No. 10 ( 2 0 1 4 )抜 刷 On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins Graham LAW ● Article ● On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins Graham LAW Abstract The increasing availability of digital editions of historical newspapers has recently brought to light claims regarding the provenance of two tales first appearing in the American press in June and October 1889, respectively. These narratives, both with American settings, are there attributed to the British novelist, Wilkie Collins, who died on September 23, 1889. The claims regarding the first tale“, The Only Girl at Overview,” are limited to a single newspaper and can be quickly dismissed. In the case of the second tale“, One August Night in ’61,” since there is no clear-cut documentary evidence to settle the case, reaching a judgment concerning provenance involves sifting a good deal of circumstantial detail, extending well beyond literary contents. The various strands relate to the American novelist who reportedly“ wrote up” up the sketch, the journals publishing and the agency distributing it, the contemporary record of payments into and out of the author’s bank account, as well as the linguistic qualities of a letter allegedly written by him, and his physical and mental condition at the time in question. In the end, though, with the insurmountable difficulty concerning the timing of the alleged letter in relation to the author’s medical condition, the balance of evidence suggests that Wilkie Collins probably had no hand in the composition not only of“ The Only Girl at Overview” but also o“f One August Night in ’61.” Though this incident tells us little about the literary practices of the aging Wilkie Collins, it reveals a good deal about the material and ideological conditions prevailing in the American popular press towards the end of the nineteenth century. -

RBWF Burns Chronicle Index

A Directory To the Articles and Features Published in “The Burns Chronicle” 1892 – 2005 Compiled by Bill Dawson A “Merry Dint” Publication 2006 The Burns Chronicle commenced publication in 1892 to fulfill the ambitions of the recently formed Burns Federation for a vehicle for “narrating the Burnsiana events of the year” and to carry important articles on Burns Clubs and the developing Federation, along with contributions from “Burnessian scholars of prominence and recognized ability.” The lasting value of the research featured in the annual publication indicated the need for an index to these, indeed the 1908 edition carried the first listings, and in 1921, Mr. Albert Douglas of Washington, USA, produced an index to volumes 1 to 30 in “the hope that it will be found useful as a key to the treasures of the Chronicle” In 1935 the Federation produced an index to 1892 – 1925 [First Series: 34 Volumes] followed by one for the Second Series 1926 – 1945. I understand that from time to time the continuation of this index has been attempted but nothing has yet made it to general publication. I have long been an avid Chronicle collector, completing my first full set many years ago and using these volumes as my first resort when researching any specific topic or interest in Burns or Burnsiana. I used the early indexes and often felt the need for a continuation of these, or indeed for a complete index in a single volume, thereby starting my labour. I developed this idea into a guide categorized by topic to aid research into particular fields. -

Wilkie Collins, a Biography

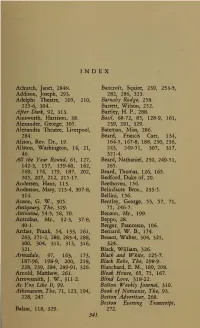

INDEX Achurch, Janet, 284n. Bancroft, Squire, 239, 253-5, Addison, Joseph, 293. 282, 286, 323. Adelphi Theatre, 205, 210, Barnaby Rudge, 258. 225-6, 304. Barrett, Wilson, 252. After Dark, 92, 313. Bartley, H. P., 288. Ainsworth, Harrison, 38. Basil, 68-72, 85, 128-9, 161, Alexander, George, 305. 239, 291, 329. Alexandra Theatre, Liverpool, Bateman, Miss, 286. 284. Beard, Francis Carr, 134, Alison, Rev. Dr., 19. 164-5, 167-8, 188, 230, 236, Allston, Washington, 14, 21, 243, 249-51, 307, 317, 46. 321-4. All the Year Round, 61, 127, Beard, Nathaniel, 230, 249-51, 142-3, 157, 159-60, 162, 265. 169, 174, 179, 187, 202, Beard, Thomas, 126, 165. 205, 207, 212, 215-17. Bedford, Duke of, 20. Andersen, Hans, 113. Beethoven, 156. Anderson, Mary, 213-4, 307-8, Belinfaute Bros., 233-5. 314. Bellini, 156. Anson, G. W., 305. Bentley, George, 53, 57, 71, Antiquary, The, 329. 75, 246-7. Antonina, 54-5, 58, 70. Benzon, Mr., 199. Antrobus, Mr., 32-3, 37-8, Beppo, 28. 40-1. Berger, Francesco, 106. Archer, Frank, 54, 133, 261, Bernard, W. B., 174. 263, 271-2, 280, 283-4, 288, Besant, Walter, 304, 321, 300, 304, 311, 313, 316, 324. 321. Black, William, 326. Armadale, 97, 163, 173, Black and White, 225-7. 187-96, 198-9, 200, 218, Black Robe, The, 298-9. 228, 239, 284, 289-91, 326. Blanchard, E. M., 189, 208. Arnold, Matthew, 261. Bleak House, 65, 75, 167. Arrowsmith, J. W., 311-2. Blind Love, 318-22. As You Like It, 99. Bolton Weekly Journal, 310. -

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church. -

Robert Burns and a Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 311 1st International Symposium on Education, Culture and Social Sciences (ECSS 2019) Robert Burns and A Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China. [email protected] Abstract. Robert Burns is a well-known Scottish poet and his poem A Red Red Rose prevails all over the world. This essay will first make a brief introduction of Robert Burns and make an analysis of A Red Red Rose in the aspects of language, imagery and rhetoric. Keywords: Robert Burns; A Red Red Rose; language; imagery; rhetoric. 1. Robert Burns’ Life Experience Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) is a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is one of the most famous poets of Scotland and is widely regarded as a Scottish national poet. Being considered as a pioneer of the Romantic Movement, Robert Burns became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism after his death. Most of his world-renowned works are written in a Scots dialect. And in the meantime, he produced a lot of poems in English. He was born in a peasant’s clay-built cottage, south of Ayr, in Alloway, South Ayrshire, Scotland in 1759 His father, William Burnes (1721–1784), is a self-educated tenant farmer from Dunnottar in the Mearns, and his mother, Agnes Broun (1732–1820), is the daughter of a Kirkoswald tenant farmer. Despite the poor soil and a heavy rent, his father still devoted his whole life to plough the land to support the whole family’s livelihood. -

The Burns Almanac for 1897

J AN U AR Y . “ ” This Tim e wi n ds 1 0 day etc . Composed 79 . 1 Letter to Mrs . Dunlop , 7 93 . f 1 Rev . Andrew Je frey died 795 . “ Co f G ra ha m py o Epistle to Robert , of Fintry , sent to 1 8 . Dr . Blacklock , 7 9 n 1 8 1 Al exa der Fraser Tytler , died 3 . ” t Copy of Robin Shure i n Hairst , se nt to Rober Ainslie, 1 789 . ’ d . Gilbert Burns initiate into St James Lodge , F A M 1 786 . fi e Th e poet de nes his religious Cr ed in a letter to Clarinda , 1 788 . ” Highland Mary , published by Alexander Gardner , 1 8 . Paisley , 94 1 1 8 . Robert Graham of Fintry , died 5 z 1 8 Dr . John Ma cken ie , died 3 7 . ’ o n t . d The p et presen t at Grand Maso ic Meeting , S An rew s 1 8 Lodge , Edinburgh , 7 7 . u z 1 8 . Y . Albany , (N ) Burns Cl b , organi ed 54 8 2 1 0 . Mrs . Burnes , mother of the poet , died The poet describes his favorite authors i n a letter to Joh n 1 8 . Murdoch , 7 3 U 1 0 . The Scottish Parliament san ctions the nion , 7 7 1 1 Letter to Peter Hill , 79 . ” B r 2 i a n a 1 1 . u n s v . u 8 , ol , iss ed 9 1 88 Letter to Clarinda , 7 . Mrs . Candlish , the Miss Smith of the Mauchline Belles , 1 8 died 54 . -

Ramsay's Pastoral and Its Legacy for the Literati A

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 28 2007 Old Bones Disinterred Once Again: Ramsay's Pastoral and its Legacy for the Literati A. M. Kinghorn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kinghorn, A. M. (2007) "Old Bones Disinterred Once Again: Ramsay's Pastoral and its Legacy for the Literati," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 382–390. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/28 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A. M. Kinghorn Old Bones Disinterred Once Again: Ramsay's Pastoral and its Legacy for the Literati Over half a century after it was fIrst published Hugh Blair accorded Allan Ramsay's Gentle Shepherd ex cathedra attention in his Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres (1783) by praising its variety in natural description and character and drawing attention to its superiority over English examples of the pastoral. Pope and Prior he dismissed as unoriginal imitators of Vergil, town dwellers whose notions of the country had little to do with the truth of nature. Ramsay on the other hand offered a landscape painter's realistic reconstruction of rural trials and tribulations perceived against a domestic background and peopled it with kenspeckle personalities -

Poor Miss Finch : a Novel

MBi 1^ m^ ^m^M^' UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN The person charging this material is responsible for its renewal or return to the library on or before the due date. The minimum fee for a lost item is $125.00, $300.00 for bound journals. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. Please note: self-stick notes may result in torn pages and lift some inks. Renew via the Telephone Center at 217-333-8400 846-262-1510 (toll-free) or [email protected]. Renew online by choosing the My Account option at- http://www.llbrary.uiuc.edu/catalog/ FEB I i^' ?T^ POOR MISS FINCH 31 ^0\)Zl WILKIE COLLINS, AUTHOR OF THE WOMAN IN WHITE," "NO NAME," "MAN AND WIFE, ETC.. ETC. IN THREE VOLUMES, VOL. I. LONDON: RICHARD BENTLEY AND SON. 1872. /.^// Rig/its reserved.) r\ . I ^Z2 V. / TO MRS. ELLIOT, (of the deanery, BRISTOL). ILL you honour me by accepting the Dedication of this book, in remembrance of an uninterrupted friendship of many years ? More than one charming bHnd girl, in fiction and in the drama, has preceded " Poor Miss Finch." But, so far as I know, bhnd- ness in these cases has been always exhibited, more or less exclusively, from the ideal and the sentimental point of view. The attempt ^ here made is to appeal to an interest of ^ another kind, by exhibiting blindness as it hr Dedication. really is. I have carefully gathered the in- formation necessary to the execution of this purpose from competent authorities of all sorts. -

Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins by Lisa Gay

Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins By Lisa Gay Mathews Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds: School of English 1993 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins By Lisa Gay Mathews Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds: School of English 1993 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. With Thanks To Alan Steele for supervising my work. To my parents for financial and moral support. To Ray and Geraldine Stoneham for teaching me to use a word processor. To Bill Forsythe of Exeter University for moral support and encouragement. And lastly, to my four beautiful cats for keeping me company whilst I wrote. Lisa Mathews: Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. October 1990 Abstract Although some good work on Collins is now beginning to emerge, complex and central elements in his fiction require fuller exploration. More consideration is due to the development of Collins's thinking and fictional techniques in the lesser-known novels, since out of a total of thirty-four published works most have received scant attention from scholars. This is particularly true of the later fiction. -

Hume Supplement

The Tattler Supplement The Jack Hume Heather & Thistle Poetry Competition June 2020 A s indicated in the main edition of O n the pages following are the sec- the Tattler, the wining entry in the 2020 ond place entry, also written by Jim Jack Hume Heather & Thistle Poetry McLaughlin, the equal third place en- competition was written by Jim tries, both written by previous winner McLaughlin of the Calgary Burns Club. Jim Fletcher of Halifax, and fifth place The epic entry of over 3,000 words is entry written by new RBANA President printed inside Henry Cairney 1 Scotland’s Bard, the Poet Robert Burns A Biography in Verse The date of January 25th in seventeen-fifty-nine, At first a shy retiring youth, and slow to court a lass, Is honoured all around the globe, this day for auld lang syne. Our lad would learn the art of love, and other friends surpass; Wi’ right guid cheer we celebrate and toast his name in turns, ‘Fair Enslavers’ could captivate, and oft times would infuse Scotland’s own Immortal Bard, the poet Robert Burns. His passionate, creative mind, that gave flight to his muse. His father William Burnes met his mother Agnes Broun A brash elan would soon emerge as youth was left behind, At a country fair in Maybole, more a village than a town. With age came self-assurance and an independent mind. Agnes kept another suitor waiting for seven years, He formed Tarbolton’s Bachelors’ Club, a forum for debate, Till she found he’d been unfaithful, confirming her worst fears. -

Wilkie Collins, the Woman in White

Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White Introduction to the Author: Wilkie Collins Wilkie Collins was born in London to William John Thomas and Harriet Collins January 8, 1824. Collins’ father was a well-known painter and the family changed houses and traveled overseas often during his childhood. After a few years in school and a short period of time as an apprentice for some tea merchants, he studied law at Lincoln’s Inn, “where he gained the legal knowledge that was to give him much material for his writing” (i). After the death of his father in February 1847, he published his first book, Memoirs of the Life of William Collins, Esq., RA in 1848. Unsure of what he wanted to do in life, Collins seriously considered becoming an artist and in 1849 he exhibited a painting at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition titled The Smuggler’s Retreat. With the publication of his first novel, Antonina; or the Fall of Rome (1850), Collins found his calling. Charles Dickens was impressed by his work and they quickly became close friends; Charles Allston Collins, Wilkie’s younger brother, would eventually marry Kate Dickens, Charles’ sister. Collins is mostly known for his novels, but his works also include short stories, plays, journalism, and biography. His close friend, Charles Dickens, actually acted and helped produce some of his plays. With the publication of The Woman in White (1860), Collins moved away from theater to focus more on novels that fell under the new genre he helped create: sensation fiction. After Dickens’ death in 1870, Collins “returned to the theatre, producing stage versions of his novels” (i).