Poor Miss Finch : a Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins

早稲田大学国際教養学部 Waseda Global Forum No. 10 ( 2 0 1 4 )抜 刷 On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins Graham LAW ● Article ● On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins Graham LAW Abstract The increasing availability of digital editions of historical newspapers has recently brought to light claims regarding the provenance of two tales first appearing in the American press in June and October 1889, respectively. These narratives, both with American settings, are there attributed to the British novelist, Wilkie Collins, who died on September 23, 1889. The claims regarding the first tale“, The Only Girl at Overview,” are limited to a single newspaper and can be quickly dismissed. In the case of the second tale“, One August Night in ’61,” since there is no clear-cut documentary evidence to settle the case, reaching a judgment concerning provenance involves sifting a good deal of circumstantial detail, extending well beyond literary contents. The various strands relate to the American novelist who reportedly“ wrote up” up the sketch, the journals publishing and the agency distributing it, the contemporary record of payments into and out of the author’s bank account, as well as the linguistic qualities of a letter allegedly written by him, and his physical and mental condition at the time in question. In the end, though, with the insurmountable difficulty concerning the timing of the alleged letter in relation to the author’s medical condition, the balance of evidence suggests that Wilkie Collins probably had no hand in the composition not only of“ The Only Girl at Overview” but also o“f One August Night in ’61.” Though this incident tells us little about the literary practices of the aging Wilkie Collins, it reveals a good deal about the material and ideological conditions prevailing in the American popular press towards the end of the nineteenth century. -

DETECTIVE NARRATIVE and the PROBLEM of ORIGINS in 19 CENTURY ENGLAND by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning Bachelor of Arts, West Chest

DETECTIVE NARRATIVE AND THE PROBLEM OF ORIGINS IN 19TH CENTURY ENGLAND by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning Bachelor of Arts, West Chester University, 1992 Master of Arts, West Virginia University, 1995 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The English Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH This dissertation was presented by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning It was defended on March 1st, 2006 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished University Service Professor, English Department, Film Studies, and the Cultural Studies Program James Seitz, Associate Professor, English Department Nancy Condee, Associate Professor, Slavic Languages and Literature and Director of the Program for Cultural Studies Dissertation Director: Colin MacCabe, Distinguished University Professor, English Literature, Film Studies, and the Cultural Studies Program ii Copyright © by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning 2006 iii DETECTIVE NARRATIVE AND THE PROBLEM OF ORIGINS IN 19TH CENTURY ENGLAND Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Working with Fredric Jameson’s understanding of genre as a “formal sedimentation” of an ideology, this study investigates the historicity of the detective narrative, what role it plays in bourgeois, capitalist culture, what ways it mediates historical processes, and what knowledge of these processes it preserves. I begin with the problem of the detective narrative’s origins. This is a complex and ultimately -

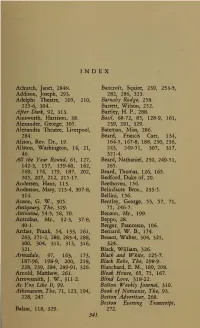

Wilkie Collins, a Biography

INDEX Achurch, Janet, 284n. Bancroft, Squire, 239, 253-5, Addison, Joseph, 293. 282, 286, 323. Adelphi Theatre, 205, 210, Barnaby Rudge, 258. 225-6, 304. Barrett, Wilson, 252. After Dark, 92, 313. Bartley, H. P., 288. Ainsworth, Harrison, 38. Basil, 68-72, 85, 128-9, 161, Alexander, George, 305. 239, 291, 329. Alexandra Theatre, Liverpool, Bateman, Miss, 286. 284. Beard, Francis Carr, 134, Alison, Rev. Dr., 19. 164-5, 167-8, 188, 230, 236, Allston, Washington, 14, 21, 243, 249-51, 307, 317, 46. 321-4. All the Year Round, 61, 127, Beard, Nathaniel, 230, 249-51, 142-3, 157, 159-60, 162, 265. 169, 174, 179, 187, 202, Beard, Thomas, 126, 165. 205, 207, 212, 215-17. Bedford, Duke of, 20. Andersen, Hans, 113. Beethoven, 156. Anderson, Mary, 213-4, 307-8, Belinfaute Bros., 233-5. 314. Bellini, 156. Anson, G. W., 305. Bentley, George, 53, 57, 71, Antiquary, The, 329. 75, 246-7. Antonina, 54-5, 58, 70. Benzon, Mr., 199. Antrobus, Mr., 32-3, 37-8, Beppo, 28. 40-1. Berger, Francesco, 106. Archer, Frank, 54, 133, 261, Bernard, W. B., 174. 263, 271-2, 280, 283-4, 288, Besant, Walter, 304, 321, 300, 304, 311, 313, 316, 324. 321. Black, William, 326. Armadale, 97, 163, 173, Black and White, 225-7. 187-96, 198-9, 200, 218, Black Robe, The, 298-9. 228, 239, 284, 289-91, 326. Blanchard, E. M., 189, 208. Arnold, Matthew, 261. Bleak House, 65, 75, 167. Arrowsmith, J. W., 311-2. Blind Love, 318-22. As You Like It, 99. Bolton Weekly Journal, 310. -

Wilkie Collins, a Biography

CHAPT ER TEN cc No Name " The next twelve months or so were among the happiest of Wilkie Collins' life. At the age of 36 he was no longer, as many had regarded him, just one of ' Mr. Dickens' young men,' but a celebrity in his own right. He had learned to enjoy success without losing his balance. His domestic life was happy and seemed relatively stable, if unconventional. He had no monetary cares and for a brief period his health was better than for some time past. He lived, as he liked to do, a full social life, and invitations to public functions, musi- cal evenings and private dinner parties showered upon him. In the winter of I860 we find him staying for the first time with those literary lion-hunters, the Monckton Milnes, at Fryston, in Yorkshire. He also came into touch with George Eliot and G. H. Lewes, and frequently attended their musical ' Saturday afternoons ' at their house near Regent's Park. The musical evening—or afternoon—was an established feature of social life in the London of the Sixties, and Wilkie was known to be a keen music-lover. His understanding of the subject was not particularly profound and we have Dickens' word, for what it is worth, that he was virtually tone-deaf, but at least it is to his credit that his favourite composer was Mozart. If music appears in one of his novels, it is almost sure to be Mozart. Laura Fairlie and Walter Hartwright play Mozart piano-duets; Uncle Joseph's— musical box plays—rather too often, one must confess ' Batti, batti,' the air from Don Giovanni; the blind Lucilla in Poor Miss 135 : 136 WILKIE COLLINS Finch plays a Mozart sonata on the piano. -

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church. -

Disabilities and Gender in the Novels of Wilkie Collins

Disabilities and Gender in the Novels of Wilkie Collins by ELIZABETH L. AGNEW Submitted to the Office of Honors Programs and Academic Scholarships Texas ARM University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for 1998-99 UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FELLOWS PROGRAM April 15, 1999 Approved as to style and content by: Pa A. Parrish, Facul Advisor Department of English Susanna Finnell, Executive Director Honors Programs and Academic Scholarships Fellows Group: Humanities Gender and Disabilities in the Novels of Wilkie Collins Elizabeth L. Agnew, (Dr. Paul A. Parrish) University Undergraduate Fellow, 1998-99, Texas A&M University, Department of English Many Victorian novelists sought to promote the importance of the individual by placing their characters in situations that allowed them to go outside society's pre-established boundaries. In spite of these novelists' intentions, a closer study of their works reveals that the writers who tried to move beyond society's expectations were often inherently trapped within them. My thesis argues that Wilkie Collins's representations of characters with disabilities show that even though Collins intended for disabilities to help characters supercede societyk expectations for them, thc Victorian context in which he was writing prevented him from completely achieving his goals. In particular, my thesis examines the ways in which Victorian attitudes toward gender influenced Co11ins's portrayals of characters with disabilities. Disabilities served to empower Collins's female characters who either physically embodied Victorian ideals of beauty and purity or who were financially independent. In contrast, women who did not fulfill these expectations were hurt by disabilities, as were all of Collins's male characters. -

GENDER and POWER in MARY ELIZABETH BRADDON's LADY AUDLEY's SECRET and WILKIE COLLINS's NO NAME by Rebecca Ann S

POWER POLITICS: GENDER AND POWER IN MARY ELIZABETH BRADDON'S LADY AUDLEY'S SECRET AND WILKIE COLLINS'S NO NAME by Rebecca Ann Smith A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to my family, friends, and committee members for their continuous support throughout this project. To my thesis chair, Dr. Oliver Buckton, I offer my sincerest appreciation for his mentorship and support throughout not only the thesis process, but throughout my academic career as both an undergraduate and as a graduate student. Dr. Buckton's literary works, along with the courses I have taken with him over the years, were the inspiration for this thesis, and I am so grateful for having the opportunity to work with him on this project. To Dr. Steven Blakemore, I am thankful for his valuable and honest commentary as it helped me to improve upon this thesis. To Dr. Magdalena Ostas, I am appreciative for her genuine interest in this manuscript and for her encouraging words along the way. I would also like to thank Dr. Johnnie Stover, Dr. Mark Scroggins, Dr. Jeffrey Galin, Dr. John Leeds, and Dr. Barclay Barrios, whose lectures, mentorship, and genuine kindness have been inspiring and encouraging. Last (but certainly not least), I am thankful to my family, my parents, my grandparents, my siblings, and my significant other, for their encouragement and love. iii ABSTRACT Author: Rebecca A. -

Sarahkmarr Awttc HC.Pdf

A Warning to the Curious Montague Rhodes James photographs and annotations Sarah K. Marr This is a high contrast version of “The Annotated Warning to the Curious”, for people who may otherwise have difficulty reading it. All the main text and annotations are black against a white background (rather than a mixture of black and grey). This does, however, make it slightly more difficult to separate the story text from accompanying notes. For general use, the original document is recommended: download it from sarahkmarr.com. Curiosity about a Warning Introduction The place on the east coast which the reader is adaptation’s success in capturing the atmosphere asked to consider is Aldeburgh. It is not very of the story. different now from what M.R. James remembered So much for place. As for time, I have used it to have been when he was a child. the dates supplied by James in his original If you have not read M.R. James’s story, “A manuscript. They are by no means definitive, and Warning to the Curious”, then I urge you to skip James himself discarded them before publication. ahead now and read it, slowly, savouring every Whatever the year, however, the mention of the word of his and ignoring all of mine. Then come full Paschal moon places the reburial of the crown back here. I, like William Ager, will wait for you. within the seven days prior to Easter Sunday. I am acutely aware of the failings of this document and in no way make the claim that it is My mother was taking a break from chemotherapy definitive. -

Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins by Lisa Gay

Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins By Lisa Gay Mathews Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds: School of English 1993 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins By Lisa Gay Mathews Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds: School of English 1993 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. With Thanks To Alan Steele for supervising my work. To my parents for financial and moral support. To Ray and Geraldine Stoneham for teaching me to use a word processor. To Bill Forsythe of Exeter University for moral support and encouragement. And lastly, to my four beautiful cats for keeping me company whilst I wrote. Lisa Mathews: Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. October 1990 Abstract Although some good work on Collins is now beginning to emerge, complex and central elements in his fiction require fuller exploration. More consideration is due to the development of Collins's thinking and fictional techniques in the lesser-known novels, since out of a total of thirty-four published works most have received scant attention from scholars. This is particularly true of the later fiction. -

Wilkie Collins, the Woman in White

Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White Introduction to the Author: Wilkie Collins Wilkie Collins was born in London to William John Thomas and Harriet Collins January 8, 1824. Collins’ father was a well-known painter and the family changed houses and traveled overseas often during his childhood. After a few years in school and a short period of time as an apprentice for some tea merchants, he studied law at Lincoln’s Inn, “where he gained the legal knowledge that was to give him much material for his writing” (i). After the death of his father in February 1847, he published his first book, Memoirs of the Life of William Collins, Esq., RA in 1848. Unsure of what he wanted to do in life, Collins seriously considered becoming an artist and in 1849 he exhibited a painting at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition titled The Smuggler’s Retreat. With the publication of his first novel, Antonina; or the Fall of Rome (1850), Collins found his calling. Charles Dickens was impressed by his work and they quickly became close friends; Charles Allston Collins, Wilkie’s younger brother, would eventually marry Kate Dickens, Charles’ sister. Collins is mostly known for his novels, but his works also include short stories, plays, journalism, and biography. His close friend, Charles Dickens, actually acted and helped produce some of his plays. With the publication of The Woman in White (1860), Collins moved away from theater to focus more on novels that fell under the new genre he helped create: sensation fiction. After Dickens’ death in 1870, Collins “returned to the theatre, producing stage versions of his novels” (i). -

Dead Secret UNABRIDGED WILKIE COLLINS Read by Nicholas Boulton

The COMPLETE CLASSICS Dead Secret UNABRIDGED WILKIE COLLINS Read by Nicholas Boulton A masterful blend of Gothic drama and romance, Wilkie Collins’s mystery novel is an exploration of illegitimacy and inheritance. Set in Cornwall, the plot foreshadows The Woman in White with its themes of doubtful identity and deception, and involves a broad array of characters. The ‘secret’ of the book’s title is the true parentage of the book’s heroine, Rosamond Treverton, which has been written down and kept in an unused room at Porthgenna Tower. This is where, 20 years later, much of the novel’s action is set. Nicholas Boulton graduated from The Guildhall School of Music and Drama, winning the BBC Carleton Hobbs Award for Radio. He has since featured in countless BBC radio dramas, narrated a plethora of award- winning audiobooks, and died a thousand deaths in various video games. Film, TV and theatre appearances include Shakespeare in Love, Total running time: 13:20:40 Game of Thrones and Wolf Hall (RSC). View our full range of titles at n-ab.com 1 The Dead Secret 10:41 27 Chapter 6: Another Surprise 14:24 2 Mrs Treverton’s bed-chamber was a large, lofty room… 11:46 28 Book 4. Chapter 1: A Plot Against the Secret 7:58 3 Sarah started to her feet with a faint scream. 12:57 29 Uncle Joseph shook his head at these last words, and… 12:21 4 Chapter 2: The Child 11:25 30 Uncle Joseph looked all round the room inquiringly… 9:03 5 Chapter 3: The Hiding of the Secret 9:49 31 ‘Ah! we are getting back into the straight road at last.’ 8:24 6 She knelt down, putting the letter on the boards… 11:10 32 Chapter 2: Outside the House 9:32 7 Book 2. -

Narratives of Blindness in the Long Nineteenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa SYMPATHETIC IMAGINATION AND THE CONCEPT OF FACE: NARRATIVES OF BLINDNESS IN THE LONG NINETEENTH CENTURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH AUGUST 2018 By Madoka Nagado Dissertation Committee: Craig Howes, Chairperson Cynthia Franklin Peter H. Hoffenberg Joseph O’Mealy John Zuern CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .......................................................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter I: Recognizing Blindness .................................................................................................. 32 Section 1 Sympathy, Imagination, and Tears in Thomas Blacklock’s Poems ........................... 32 Section 2 The Self-/Portraits of Blindness: James Wilson’s Auto/biography .......................... 52 Chapter II: Representing Blindness .............................................................................................