On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilkie Collins, a Biography

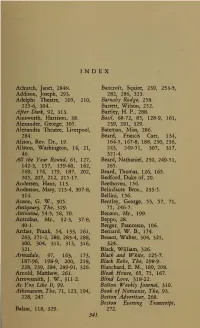

INDEX Achurch, Janet, 284n. Bancroft, Squire, 239, 253-5, Addison, Joseph, 293. 282, 286, 323. Adelphi Theatre, 205, 210, Barnaby Rudge, 258. 225-6, 304. Barrett, Wilson, 252. After Dark, 92, 313. Bartley, H. P., 288. Ainsworth, Harrison, 38. Basil, 68-72, 85, 128-9, 161, Alexander, George, 305. 239, 291, 329. Alexandra Theatre, Liverpool, Bateman, Miss, 286. 284. Beard, Francis Carr, 134, Alison, Rev. Dr., 19. 164-5, 167-8, 188, 230, 236, Allston, Washington, 14, 21, 243, 249-51, 307, 317, 46. 321-4. All the Year Round, 61, 127, Beard, Nathaniel, 230, 249-51, 142-3, 157, 159-60, 162, 265. 169, 174, 179, 187, 202, Beard, Thomas, 126, 165. 205, 207, 212, 215-17. Bedford, Duke of, 20. Andersen, Hans, 113. Beethoven, 156. Anderson, Mary, 213-4, 307-8, Belinfaute Bros., 233-5. 314. Bellini, 156. Anson, G. W., 305. Bentley, George, 53, 57, 71, Antiquary, The, 329. 75, 246-7. Antonina, 54-5, 58, 70. Benzon, Mr., 199. Antrobus, Mr., 32-3, 37-8, Beppo, 28. 40-1. Berger, Francesco, 106. Archer, Frank, 54, 133, 261, Bernard, W. B., 174. 263, 271-2, 280, 283-4, 288, Besant, Walter, 304, 321, 300, 304, 311, 313, 316, 324. 321. Black, William, 326. Armadale, 97, 163, 173, Black and White, 225-7. 187-96, 198-9, 200, 218, Black Robe, The, 298-9. 228, 239, 284, 289-91, 326. Blanchard, E. M., 189, 208. Arnold, Matthew, 261. Bleak House, 65, 75, 167. Arrowsmith, J. W., 311-2. Blind Love, 318-22. As You Like It, 99. Bolton Weekly Journal, 310. -

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church. -

Poor Miss Finch : a Novel

MBi 1^ m^ ^m^M^' UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN The person charging this material is responsible for its renewal or return to the library on or before the due date. The minimum fee for a lost item is $125.00, $300.00 for bound journals. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. Please note: self-stick notes may result in torn pages and lift some inks. Renew via the Telephone Center at 217-333-8400 846-262-1510 (toll-free) or [email protected]. Renew online by choosing the My Account option at- http://www.llbrary.uiuc.edu/catalog/ FEB I i^' ?T^ POOR MISS FINCH 31 ^0\)Zl WILKIE COLLINS, AUTHOR OF THE WOMAN IN WHITE," "NO NAME," "MAN AND WIFE, ETC.. ETC. IN THREE VOLUMES, VOL. I. LONDON: RICHARD BENTLEY AND SON. 1872. /.^// Rig/its reserved.) r\ . I ^Z2 V. / TO MRS. ELLIOT, (of the deanery, BRISTOL). ILL you honour me by accepting the Dedication of this book, in remembrance of an uninterrupted friendship of many years ? More than one charming bHnd girl, in fiction and in the drama, has preceded " Poor Miss Finch." But, so far as I know, bhnd- ness in these cases has been always exhibited, more or less exclusively, from the ideal and the sentimental point of view. The attempt ^ here made is to appeal to an interest of ^ another kind, by exhibiting blindness as it hr Dedication. really is. I have carefully gathered the in- formation necessary to the execution of this purpose from competent authorities of all sorts. -

Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins by Lisa Gay

Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins By Lisa Gay Mathews Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds: School of English 1993 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins By Lisa Gay Mathews Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds: School of English 1993 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. With Thanks To Alan Steele for supervising my work. To my parents for financial and moral support. To Ray and Geraldine Stoneham for teaching me to use a word processor. To Bill Forsythe of Exeter University for moral support and encouragement. And lastly, to my four beautiful cats for keeping me company whilst I wrote. Lisa Mathews: Crime and Subversion in the Later Fiction of Wilkie Collins Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. October 1990 Abstract Although some good work on Collins is now beginning to emerge, complex and central elements in his fiction require fuller exploration. More consideration is due to the development of Collins's thinking and fictional techniques in the lesser-known novels, since out of a total of thirty-four published works most have received scant attention from scholars. This is particularly true of the later fiction. -

Wilkie Collins, the Woman in White

Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White Introduction to the Author: Wilkie Collins Wilkie Collins was born in London to William John Thomas and Harriet Collins January 8, 1824. Collins’ father was a well-known painter and the family changed houses and traveled overseas often during his childhood. After a few years in school and a short period of time as an apprentice for some tea merchants, he studied law at Lincoln’s Inn, “where he gained the legal knowledge that was to give him much material for his writing” (i). After the death of his father in February 1847, he published his first book, Memoirs of the Life of William Collins, Esq., RA in 1848. Unsure of what he wanted to do in life, Collins seriously considered becoming an artist and in 1849 he exhibited a painting at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition titled The Smuggler’s Retreat. With the publication of his first novel, Antonina; or the Fall of Rome (1850), Collins found his calling. Charles Dickens was impressed by his work and they quickly became close friends; Charles Allston Collins, Wilkie’s younger brother, would eventually marry Kate Dickens, Charles’ sister. Collins is mostly known for his novels, but his works also include short stories, plays, journalism, and biography. His close friend, Charles Dickens, actually acted and helped produce some of his plays. With the publication of The Woman in White (1860), Collins moved away from theater to focus more on novels that fell under the new genre he helped create: sensation fiction. After Dickens’ death in 1870, Collins “returned to the theatre, producing stage versions of his novels” (i). -

Narratives of Blindness in the Long Nineteenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa SYMPATHETIC IMAGINATION AND THE CONCEPT OF FACE: NARRATIVES OF BLINDNESS IN THE LONG NINETEENTH CENTURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH AUGUST 2018 By Madoka Nagado Dissertation Committee: Craig Howes, Chairperson Cynthia Franklin Peter H. Hoffenberg Joseph O’Mealy John Zuern CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .......................................................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter I: Recognizing Blindness .................................................................................................. 32 Section 1 Sympathy, Imagination, and Tears in Thomas Blacklock’s Poems ........................... 32 Section 2 The Self-/Portraits of Blindness: James Wilson’s Auto/biography .......................... 52 Chapter II: Representing Blindness ............................................................................................. -

Wilkie Collins and Copyright

Wilkie Collins and Copyright Wilkie Collins and Copyright Artistic Ownership in the Age of the Borderless Word s Sundeep Bisla The Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright © 2013 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bisla, Sundeep, 1968– Wilkie Collins and copyright : artistic ownership in the age of the borderless word / Sundeep Bisla. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1235-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1235-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9337-9 (cd-rom) ISBN-10: 0-8142-9337-9 (cd-rom) Collins, Wilkie, 1824–1889—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Intellectual property in literature. 3. Intellectual property—History—19th century. 4. Copyright—History—19th century. I. Title. PR4497.B57 2013 823'.8—dc23 2013010878 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 s CONTENTS S Acknowledgments vii Preface A Spot of Ink, More Than a Spot of Bother ix Chapter 1 Introduction: Wilkie Collins, Theorist of Iterability 1 Part One. The Fictions of Settling Chapter 2 The Manuscript as Writer’s Estate in Basil 57 Chapter 3 The Woman in White: The Perils of Attempting to Discipline the Transatlantic, Transhistorical Narrative 110 Part Two. The Fictions of Breaking Chapter -

Introduction: the Sense of Unending. Closing Charlotte Brontë's 'Emma'

Notes Introduction: The Sense of Unending. Closing Charlotte Brontë’s ‘Emma’ 1. Charlotte Brontë, The Letters of Charlotte Brontë, with a Selection of Letters by Family and Friends, ed. Margaret Smith, 3 vols (Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press, 1995–2004), I, p. 319, my italics. From now on indicated as Letters. 2. Philip Rhodes, ‘A Medical Appraisal of the Brontës’, Brontë Society Transactions, 16.82 (1972), p. 107. Winifred Gérin writes that Charlotte’s ‘death certificate made no mention of her pregnancy; it gave “Phthisis” as the sole cause of death, uniting her thus, as if proof of any closer ties were needed, with the sisters and brother who had gone before [...]. Little Dr. Dugdale, barely begin- ning his long career [...], carried into old age the regret and humiliation of losing his first – and most illustrious – patient. Of all the babies he lost, he used to say, the one that grieved him most was Charlotte Brontë’s’. Charlotte Brontë: The Evolution of Genius (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967), p. 566. 3. Lucasta Miller, The Brontë Myth (London: Vintage, 2001), p. 2. 4. See Robert Keffe, Charlotte Brontë’s World of Death (Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1979), and John Maynard, Charlotte Brontë and Sexuality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984). 5. Alfred Tennyson, Tennyson’s Poetry, ed. Robert W. Hill (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999), p. 128. 6. As for Emily Brontë, critics agree that she had probably begun to write a fol- low-up to Wuthering Heights. This opinion is supported by the presence of a letter (now at the Brontë Parsonage Museum) written by editor T. -

Wilkie Collins and His Victorian Readers: a Study in the Rhetoric of Authorship

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1978 Wilkie Collins and His Victorian Readers: A Study in the Rhetoric of Authorship Sue Lonoff The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2198 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS This malarial was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Pags(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent peges. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Whan an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the pege in the adjacent frame. -

The Cambridge Companion to Wilkie Collins

THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO WILKIE COLLINS Wilkie Collins was one of the most popular writers of the nineteenth century. He is best known for The Woman in White, which inaugurated the sensation novel in the 1860s, and The Moonstone, one of the first detective novels; but he wrote more than twenty novels, plays and numerous short stories during a career that spanned four decades. This Companion offers a fascinating overview of Collins’s writing. In a wide range of essays by leading scholars, it traces the development of his career, his position as a writer and his complex relation to contemporary cultural movements and debates. Collins’s exploration of the tensions that lay beneath Victorian society is analysed through a variety of critical approaches. A chronology and guide to further reading are provided, making this book an indispensable guide for all those interested in Wilkie Collins and his work. JENNY BOURNE TAYLOR is Professor of English at the University of Sussex. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2006 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2006 THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO WILKIE COLLINS EDITED BY JENNY BOURNE TAYLOR Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2006 CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sa˜o Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB22RU,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521549660 © Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

W I L K I E F I C T I 0 N 1959

W I L K I E C 0 L L I N S A CRITI'CAL S U R V E Y 0 F H I S :P R 0 S E F I C T I 0 N WI T H .A B I B L I 0 G R A P H Y by R.V. Andrew, M.A., B. Ed. A Thesis :Presented under the :Promotorship of :Professor R.E. Davies, M.A., :Ph. D., to the Faculty of Arts and :Philosophy in part fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor Litterarum in the Pbtchefstroom Univer~ity for C.H.E. 1959 ' TO J. W. DANEEL A C K N 0 W L E D G E M E N T S First of all I must pay tribute to the antiqua :ri rn ~ - b ooKsellers of Britain who searched for a nd found for :r; ::_; Colli ns items and other works not easily come by? -v-,rh ,~ sent these volumes to South Africa, often on approval and ah·mys on trust. I should like to record my indebcedness to Kenn ei -~ .:. Robins on for the clear and authentic picture of Colli:ru; for his keen critical insight, especially as regards 1Jj. discerning criticism of Collins's lat~r novels and his appraisal of Collins as a vn·iter . It seeF.s to me a great :'lity that Ashley,. in his vJI~~I~-- · COI~~' found i t necessaloy to limit himself to less tha n o ~~~ "; h.und5::ed. a::.1d f j_fty pagr:;s. -

XIX CENTURY FICTION PART I Jarndyce

XIX CENTURY FICTION PART I Jarndyce XIX CENTURY FICTION in original bindings, including fine three-deckers PART I: A-K Jarndyce Bloomsbury 2019 CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF BOOKSELLING Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London www.jarndyce.co.uk WC1B 3PA VAT.No.: GB 524 0890 57 CATALOGUE CCXXXVIII SUMMER 2019 XIX CENTURY FICTION PART I: A-K Catalogue: Brian Lake. Production: Carol Murphy & Ed Lake. All items are London-published and in VERY GOOD condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (20%) to customers within the EU. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, a fee will be added towards the costs of conversion. High resolution images are available for all items, on request; please email: [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE include (price £10.00 each unless otherwise stated): Turn of the Century; Women Writers Parts I, II & III - Novels, 1740-1940, & Part IV: For, By & About Women; Books & Pamphlets 1505-1833; The Museum: A Jarndyce Miscellany; Plays 1623-1980; European Literature in Translation; Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; Conduct & Education (£5); JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: The Dickens Catalogue; Pantomimes, Extravaganzas & Burlesques; English Language, including dictionaries. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. Valuations for insurance or probate can be undertaken anywhere, by arrangement.