Wilkie Collins and Copyright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins

早稲田大学国際教養学部 Waseda Global Forum No. 10 ( 2 0 1 4 )抜 刷 On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins Graham LAW ● Article ● On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins Graham LAW Abstract The increasing availability of digital editions of historical newspapers has recently brought to light claims regarding the provenance of two tales first appearing in the American press in June and October 1889, respectively. These narratives, both with American settings, are there attributed to the British novelist, Wilkie Collins, who died on September 23, 1889. The claims regarding the first tale“, The Only Girl at Overview,” are limited to a single newspaper and can be quickly dismissed. In the case of the second tale“, One August Night in ’61,” since there is no clear-cut documentary evidence to settle the case, reaching a judgment concerning provenance involves sifting a good deal of circumstantial detail, extending well beyond literary contents. The various strands relate to the American novelist who reportedly“ wrote up” up the sketch, the journals publishing and the agency distributing it, the contemporary record of payments into and out of the author’s bank account, as well as the linguistic qualities of a letter allegedly written by him, and his physical and mental condition at the time in question. In the end, though, with the insurmountable difficulty concerning the timing of the alleged letter in relation to the author’s medical condition, the balance of evidence suggests that Wilkie Collins probably had no hand in the composition not only of“ The Only Girl at Overview” but also o“f One August Night in ’61.” Though this incident tells us little about the literary practices of the aging Wilkie Collins, it reveals a good deal about the material and ideological conditions prevailing in the American popular press towards the end of the nineteenth century. -

Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Behavior in Suhum, Ghana1

European Journal of Educational Sciences, EJES March 2017 edition Vol.4, No.1 ISSN 1857- 6036 Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Behavior in Suhum, Ghana1 Charles Quist-Adade, PhD Kwantlen Polytechnic University doi: 10.19044/ejes.v4no1a1 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/ejes.v4no1a1 Abstract This study sought to investigate the key factors that influence teenage reproductive and sexual behaviours and how these behaviours are likely to be influenced by parenting styles of primary caregivers of adolescents in Suhum, in Eastern Ghana. The study aimed to identify risky sexual and reproductive behaviours and their underlying factors among in-school and out-of-school adolescents and how parenting styles might play a role. While the data from the study provided a useful snapshot and a clear picture of sexual and reproductive behaviours of the teenagers surveyed, it did not point to any strong association between parental styles and teens’ sexual reproductive behaviours. Keywords: Parenting styles; parents; youth sexuality; premarital sex; teenage pregnancy; adolescent sexual and reproductive behavior. Introduction This research sought to present a more comprehensive look at teenage reproductive and sexual behaviours and how these behaviours are likely to be influenced by parenting styles of primary caregivers of adolescents in Suhum, in Eastern Ghana. The study aimed to identify risky sexual and reproductive behaviours and their underlying factors among in- school and out-of-school adolescents and how parenting styles might play a role. It was hypothesized that a balance of parenting styles is more likely to 1 Acknowledgements: I owe debts of gratitude to Ms. -

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

DETECTIVE NARRATIVE and the PROBLEM of ORIGINS in 19 CENTURY ENGLAND by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning Bachelor of Arts, West Chest

DETECTIVE NARRATIVE AND THE PROBLEM OF ORIGINS IN 19TH CENTURY ENGLAND by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning Bachelor of Arts, West Chester University, 1992 Master of Arts, West Virginia University, 1995 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The English Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH This dissertation was presented by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning It was defended on March 1st, 2006 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished University Service Professor, English Department, Film Studies, and the Cultural Studies Program James Seitz, Associate Professor, English Department Nancy Condee, Associate Professor, Slavic Languages and Literature and Director of the Program for Cultural Studies Dissertation Director: Colin MacCabe, Distinguished University Professor, English Literature, Film Studies, and the Cultural Studies Program ii Copyright © by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning 2006 iii DETECTIVE NARRATIVE AND THE PROBLEM OF ORIGINS IN 19TH CENTURY ENGLAND Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Working with Fredric Jameson’s understanding of genre as a “formal sedimentation” of an ideology, this study investigates the historicity of the detective narrative, what role it plays in bourgeois, capitalist culture, what ways it mediates historical processes, and what knowledge of these processes it preserves. I begin with the problem of the detective narrative’s origins. This is a complex and ultimately -

Wilkie Collins, a Biography

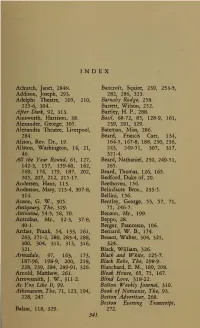

INDEX Achurch, Janet, 284n. Bancroft, Squire, 239, 253-5, Addison, Joseph, 293. 282, 286, 323. Adelphi Theatre, 205, 210, Barnaby Rudge, 258. 225-6, 304. Barrett, Wilson, 252. After Dark, 92, 313. Bartley, H. P., 288. Ainsworth, Harrison, 38. Basil, 68-72, 85, 128-9, 161, Alexander, George, 305. 239, 291, 329. Alexandra Theatre, Liverpool, Bateman, Miss, 286. 284. Beard, Francis Carr, 134, Alison, Rev. Dr., 19. 164-5, 167-8, 188, 230, 236, Allston, Washington, 14, 21, 243, 249-51, 307, 317, 46. 321-4. All the Year Round, 61, 127, Beard, Nathaniel, 230, 249-51, 142-3, 157, 159-60, 162, 265. 169, 174, 179, 187, 202, Beard, Thomas, 126, 165. 205, 207, 212, 215-17. Bedford, Duke of, 20. Andersen, Hans, 113. Beethoven, 156. Anderson, Mary, 213-4, 307-8, Belinfaute Bros., 233-5. 314. Bellini, 156. Anson, G. W., 305. Bentley, George, 53, 57, 71, Antiquary, The, 329. 75, 246-7. Antonina, 54-5, 58, 70. Benzon, Mr., 199. Antrobus, Mr., 32-3, 37-8, Beppo, 28. 40-1. Berger, Francesco, 106. Archer, Frank, 54, 133, 261, Bernard, W. B., 174. 263, 271-2, 280, 283-4, 288, Besant, Walter, 304, 321, 300, 304, 311, 313, 316, 324. 321. Black, William, 326. Armadale, 97, 163, 173, Black and White, 225-7. 187-96, 198-9, 200, 218, Black Robe, The, 298-9. 228, 239, 284, 289-91, 326. Blanchard, E. M., 189, 208. Arnold, Matthew, 261. Bleak House, 65, 75, 167. Arrowsmith, J. W., 311-2. Blind Love, 318-22. As You Like It, 99. Bolton Weekly Journal, 310. -

Wilkie Collins, a Biography

CHAPT ER TEN cc No Name " The next twelve months or so were among the happiest of Wilkie Collins' life. At the age of 36 he was no longer, as many had regarded him, just one of ' Mr. Dickens' young men,' but a celebrity in his own right. He had learned to enjoy success without losing his balance. His domestic life was happy and seemed relatively stable, if unconventional. He had no monetary cares and for a brief period his health was better than for some time past. He lived, as he liked to do, a full social life, and invitations to public functions, musi- cal evenings and private dinner parties showered upon him. In the winter of I860 we find him staying for the first time with those literary lion-hunters, the Monckton Milnes, at Fryston, in Yorkshire. He also came into touch with George Eliot and G. H. Lewes, and frequently attended their musical ' Saturday afternoons ' at their house near Regent's Park. The musical evening—or afternoon—was an established feature of social life in the London of the Sixties, and Wilkie was known to be a keen music-lover. His understanding of the subject was not particularly profound and we have Dickens' word, for what it is worth, that he was virtually tone-deaf, but at least it is to his credit that his favourite composer was Mozart. If music appears in one of his novels, it is almost sure to be Mozart. Laura Fairlie and Walter Hartwright play Mozart piano-duets; Uncle Joseph's— musical box plays—rather too often, one must confess ' Batti, batti,' the air from Don Giovanni; the blind Lucilla in Poor Miss 135 : 136 WILKIE COLLINS Finch plays a Mozart sonata on the piano. -

A Tale of Two Cities

LEVEL 5 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme A Tale of Two Cities Charles Dickens Summary EASYSTARTS A Tale of Two Cities was Charles Dickens’s second historical novel and is set in the late eighteenth century during the period of the French Revolution. It was originally published in thirty-one weekly instalments between April LEVEL 2 and November 1859. Chapters 1–2: The version of the story published here LEVEL 3 begins in the last decades of the eighteenth century, when the poor and oppressed of France were at last beginning to plan the downfall of the aristocracy. The book opens LEVEL 4 with the description of a poor suburb of Paris called Saint Antoine. A wine barrel is accidentally damaged and the poor people of the area rush to drink the wine from About the author the street. The scene is witnessed by the local wine shop LEVEL 5 Charles Dickens, a world-famous author, born in 1812, owner Monsieur Defarge, who is also a revolutionary was the son of a clerk in the Navy office. His irresponsible leader. Monsieur Defarge is looking after his former parents ran into great debt and when Dickens was twelve, employer, Dr Manette, who has recently been released LEVEL 6 his father was placed in a debtors’ prison and the boy from prison after spending many years locked up in the was put to work in a factory for some months. Dickens’s Bastille. Dr Manette spends his time in his room making intense misery in this place made a profound impression shoes – a skill he learned while in prison. -

Situational Ethics in Wilkie Collins' "Woman in White" and "Moonstone"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 Situational Ethics in Wilkie Collins' "Woman in White" and "Moonstone" Flora Christina Buckalew College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Buckalew, Flora Christina, "Situational Ethics in Wilkie Collins' "Woman in White" and "Moonstone"" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625596. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-bjv4-6j20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SITUATIONAL ETHICS IN WILKIE COLLINS' WOMAN IN WHITE AND MOONSTONE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Flora C. Buckalew 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Cl — '_________________ Flora C. Buckalew Approved, December 1990 Deborah D. Morse W . O&y&SuL. John W. Conlee Z. Terry/L7 Meyers/ ii DEDICATION The author would like to thank her parents, Dr. Robert Jo Buckalew and Mrs. Flora K. Buckalew, and her sister, Miss Faye R. Buckalew, for their love and support. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............... v ABSTRACT ........................ -

For Art's Sake

GHENT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ARTS AND PHILOSOPHY 2008-2009 FOR ART’S SAKE COMPARISON OF OSCAR WILDE‘S THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY AND OUIDA‘S UNDER TWO FLAGS Hanne Lapierre May 2009 Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Dr. Kate Macdonald fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of ―Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels-Spaans‖. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Kate Macdonald who oversaw the building up of the main body of the text. Her remarks were very helpful for writing the final version of this paper. I also thank Dr. Andrew King for giving me access to some of his interesting books on Ouida and for his remarkable enthusiasm on the subject. Contents Acknowledgements 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................1 2. On Ouida…………………………………………………………………4 3. Aestheticism……………………………………………………………..13 3.1. Introducing Aestheticism 13 3.2. The Origins of Aestheticism 15 3.3. Aspects of Aestheticism 17 3.3.1. Aestheticism as a View of Life 17 3.3.2. Aestheticism as a View of Art 21 3.3.2.1. The extraordinary status of the artist 21 3.3.2.2. An unlimited devotion to art 23 3.3.2.3. Rejection of conventional moral values 24 3.3.2.4. Superiority of form over content 30 3.3.2.5. Conclusion 33 4. Consumer Culture……………………………………………………...34 4.1. The Rise of Consumer Culture 34 4.2. Advertising 42 4.3. The Commodity 49 4.3.1. Use Value and Exchange Value 49 4.3.2. Being vs. Having 52 4.3.3. Having vs. Appearing 53 4.4. -

The Moonstone

The Moonstone Wilkie Collins Retold by David Wharry Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn potter Contents Page Introduction 4 Taken From an Old Family Letter 5 Part 1 The Loss of the Diamond 7 Chapter 1 A Record of the Facts 7 Chapter 2 Three Indian Men 8 Chapter 3 The Will 9 Chapter 4 A Shadow 13 Chapter 5 Rivals 14 Chapter 6 The Moonstone 17 Chapter 7 The Indians Return 18 Chapter 8 The Theft 21 Chapter 9 Sergeant Cuff Arrives 26 Chapter 10 The Search Begins 29 Chapter 11 Rosanna 30 Chapter 12 Rachel's Decision 34 Chapter 13 A Letter 36 Chapter 14 The Shivering Sands 39 Chapter 15 To London 44 Part 2 The Discovery of the Truth 46 First Narrative 46 Chapter 1 A Strange Mistake 46 Chapter 2 Rumours and Reputations 49 Chapter 3 Placing the Books 54 Chapter 4 A Silent Listener 56 Chapter 5 Brighton 59 Second Narrative 65 Chapter 1 Money-Lending 65 Chapter 2 Next June 67 2 Third Narrative 69 Chapter 1 Franklin's Return 69 Chapter 2 Instructions 71 Chapter 3 Rosanna's Letter 73 Chapter 4 Return to London 76 Chapter 5 Witness 78 Chapter 6 Investigating 82 Chapter 7 Lost Memory 85 Chapter 8 Opium 87 Fourth Narrative 90 Fifth Narrative 94 Sixth Narrative 100 3 Introduction 'Look, Gabriel!' cried Miss Rachel, flashing the jewel in the sunlight. It was as large as a bird's egg, the colour of the harvest moon, a deep yellow that sucked your eyes into it so you saw nothing else. -

Azu Etd Mr 2012 0090 Sip1 M.Pdf

Truth and Justice in The Moonstone and Bleak House Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Keffeler, Kristina Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 15:41:49 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/244411 Abstract Truth and justice seem to have a natural connection, especially in novels where detectives investigate the mysteries behind a crime. The plot of a detective story is based on the assumption that once the facts are discovered, the truth will come out and justice will be served. This thesis explores the interaction between truth and justice in Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone and Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. While investigations may reveal the truth, this does not always lead to justice. Authors can uphold or deviate from traditional norms to reinforce or undermine the expectation that justice will be served. Keffeler 1 Truth and Justice in The Moonstone and Bleak House Introduction Victorians placed a high value on honesty. The cultural norm of the period was that people were expected to tell the truth (Kucich 6). There are many references by people such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and W. E. H. Lecky about how Victorians took pride in being candid and sincere. This emphasis on honesty led to moral values that placed great importance on the truth (Kucich 8). -

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church.