A Tale of Two Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Mis Education Study Guide.Indd

And remember The truth that once was spoken, To love another person Is to see the face of God. THE CHARACTERS QUESTIONS / • In the end, what does Jean society who have lost their DISCUSSION IDEAS Valjean prove with his life? humanity and become brutes. Are there people in our society • Javert is a watchdog of the legal who fi t this description? • What is Hugo’s view of human process. He applies the letter nature? Is it naturally good, of the law to every lawbreaker, • Compare Marius as a romantic fl awed by original sin, or without exception. Should he hero with the romantic heroes of somewhere between the two? have applied other standards to a other books, plays or poems of man like Jean Valjean? the romantic period. • Describe how Hugo uses his characters to describe his view • Today, many believe, like Javert, • What would Eponine’s life have of human nature. How does that no mercy should be shown been like if she had not been each character represent another to criminals. Do you agree with killed at the barricade? facet of Hugo’s view? this? Why? • Although they are only on stage • Discuss Hugo’s undying belief • What does Javert say about his a brief time, both Fantine and that man can become perfect. past that is a clue to his nature? Gavroche have vital roles to How does Jean Valjean’s life play in Les Misérables and a illustrate this belief? • What fi nally destroys Javert? deep impact on the audience. Hugo says he is “an owl forced What makes them such powerful to gaze with an eagle.” What characters? What do they have does this mean? in common? Name some other • Discuss the Thénardiers as characters from literature that individuals living in a savage appear for a short time, but have a lasting impact. -

A Tale of Two Cities - Walsh 76

A TALE OF TWO CITIES - WALSH 76. SCENE 19 (The scene shifts to the Manettes’ home in London. Lucie and Miss Pross enter. Lucie is upset. Miss Pross has to work hard to keep up.) MISS PROSS Miss Lucie! Miss Lucie! What on earth is wrong? LUCIE He has oppressed no man. He has imprisoned no man. Rather than harshly exacting payment of his dues, he relinquished them of his own free will. He left instructions to his steward to give the people what little there was to give. And for this service, he is to be imprisoned. MISS PROSS What are you talking about, Miss Lucie? LUCIE The decree. MISS PROSS What decree? There have been so many decrees I’ve lost count. LUCIE They are arresting emigrants. (The doorbell rings.) MISS PROSS But you remember what Mister Carton said, how unreliable the news is from France during these troubled times. LUCIE I must go to him. MISS PROSS You what? LUCIE If I leave now, there is a chance I may overtake him before he arrives in Paris. (Carton enters.) MISS PROSS Oh, Mister Carton! Thank goodness. Do talk some sense into her. A TALE OF TWO CITIES - WALSH 77. CARTON I, Miss Pross? When have I ever been known to talk sense? MISS PROSS She’s got it in her head to go to Paris! CARTON She... what? Lucie, you can’t be serious. LUCIE I am quite serious. Charles would do no less if our positions were reversed. CARTON Charles would not have let you go to Paris in the first place. -

To What Extent Is “A Tale of Two Cities” by Charles Dickens a Historical Or a Romance Novel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TED Ankara College IB Thesis TED ANKARA COLLEGE FOUNDATION PRIVATE HIGH SCHOOL Extended Essay Research Question: To what extent is “A Tale of Two Cities” by Charles Dickens a historical or a romance novel. Mehmet Uğur TÜRKYILMAZ Supervisor: Dilek Göktaş School Code: 1129 Candidate Number: D-1129-084 Word Count: 3260 1 Contents 1 Abstract 1 2 Introduction 2 3 Historical Novel and Features of “A Tale of Two Cities” as a Historical Novel 5 4 Romance Novel and Features of “A Tale of Two Cities as a Romance Novel 8 5 Conclusion 11 6 Bibliography 13 2 Mehmet Uğur Türkyılmaz D1129-084 Abstract This extended essay aims to analyse “A Tale of Two Cities”, written by Charles Dickens in 1859, from two different perspectives: historical novel and romantic novel. The novel is set in the period of French Revolution, and the historical setting is an important aspect of this novel. There is also a romantic relationship developing between two young people. This dual nature of the book, the fact that it encompasses love, guilt, compassion, justice, sacrifice, revenge and loyalty, and the detailed and realistic narration of the French revolution were the main reasons behind the selection of this novel. This essay compares the historical features and the romantic features of the novel. Historical novel and romantic novel types of literature was first defined, and then the novel was examined according to the definitions. Word Count: 131 3 Mehmet Uğur Türkyılmaz D1129-084 Introduction Charles Dickens is one of the most important figures in British literature, especially that of Victorian era. -

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

A Tale of Two Cities By Charles Dickens Book 2: The Golden Thread Chapter 11: A Companion Picture Sydney,” said Mr. Stryver, on that self-same night, or morning, to his jackal; “mix another bowl of punch; I have something to say to you.” Sydney had been working double tides that night, and the night before, and the night before that, and a good many nights in succession, making a grand clearance among Mr. Stryver’s papers before the setting in of the long vacation. The clearance was effected at last; the Stryver arrears were handsomely fetched up; everything was got rid of until November should come with its fogs atmospheric, and fogs legal, and bring grist to the mill again. Sydney was none the livelier and none the soberer for so much application. It had taken a deal of extra wet-towelling to pull him through the night; a correspondingly extra quantity of wine had preceded the towelling; and he was in a very damaged condition, as he now pulled his turban off and threw it into the basin in which he had steeped it at intervals for the last six hours. “Are you mixing that other bowl of punch?” said Stryver the portly, with his hands in his waistband, glancing round from the sofa where he lay on his back. “I am.” A Tale of Two Cities: Book 2, Chapter 11 by Charles Dickens “Now, look here! I am going to tell you something that will rather surprise you, and that perhaps will make you think me not quite as shrewd as you usually do think me. -

A Tale of Two Cities

LEVEL 5 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme A Tale of Two Cities Charles Dickens Summary EASYSTARTS A Tale of Two Cities was Charles Dickens’s second historical novel and is set in the late eighteenth century during the period of the French Revolution. It was originally published in thirty-one weekly instalments between April LEVEL 2 and November 1859. Chapters 1–2: The version of the story published here LEVEL 3 begins in the last decades of the eighteenth century, when the poor and oppressed of France were at last beginning to plan the downfall of the aristocracy. The book opens LEVEL 4 with the description of a poor suburb of Paris called Saint Antoine. A wine barrel is accidentally damaged and the poor people of the area rush to drink the wine from About the author the street. The scene is witnessed by the local wine shop LEVEL 5 Charles Dickens, a world-famous author, born in 1812, owner Monsieur Defarge, who is also a revolutionary was the son of a clerk in the Navy office. His irresponsible leader. Monsieur Defarge is looking after his former parents ran into great debt and when Dickens was twelve, employer, Dr Manette, who has recently been released LEVEL 6 his father was placed in a debtors’ prison and the boy from prison after spending many years locked up in the was put to work in a factory for some months. Dickens’s Bastille. Dr Manette spends his time in his room making intense misery in this place made a profound impression shoes – a skill he learned while in prison. -

The Plot Structure and Theme in Charles Dickens's Famous Novel “A Tale of Two Cities”

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development 2014; 1(6): 71-73 The plot structure and theme in Charles Dickens’s famous IJMRD 2014; 1(6): 71-73 www.allsubjectjournal.com novel “A Tale of Two Cities” Received: 23-10-2014 Accepted: 11-11-2014 e-ISSN: 2349-4182 Krishma Chaudhary p-ISSN: 2349-5979 Abstract Krishma Chaudhary The present research work deals with the development of ‘plot’ and ‘theme’ of Charles Dickens’s famous (M. phil. Scholar) Department of novel “A Tale of Two Cities” 1859. It is one of the famous novels by Dickens which set in London and English Chaudhary Devi Lal Paris before and during the French Revolution. However, this novel follows the lives of several University, Sirsa, Haryana, characters through these events but it has fewer characters and sub-plots than a typical Dickens novel. India. The forty five chapter novel was published in 31 weekly instalments in Dickens’s new literary periodical titled “A Tale of Two Cities”. The first weekly instalment of it ran in the first issue of “All the Year Round” on 30 April 1859 and the last ran thirty weeks later, on 26 November 1859. “A Tale of Two Cities” is one of only two works of historical fiction by Charles Dickens. In this essay we discussed the plot construction and the themes of the novel “A Tale of Two Cities” written by Charles Dickens. Keywords: Dickens, A tale of Two Cities, plot structure, theme. 1. Introduction Charles Dickens (1812-1870) is a creator of realistic novels. The picture which he painted of the English social world is one of the richest in the whole range of literature. -

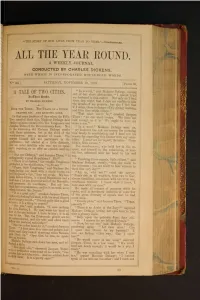

All the Year Round. a Weekly Journal

"THE STORY OF OUR LIVES FROM YEAR TO YEAR."---SHAKEsPEArE. ALL THE YEAR ROUND. A WEEKLY JOURNAL. CONDUCTED BY CHARLES DICKENS. WITH WHICH IS INCORPORATED HOUSEHOLD WORDS. SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 1859. N°- 30.] [PRICE 2d. "In a word," said Madame Defarge, coming A TALE OF TWO CITIES. out of her short abstraction, "I cannot trust In Three Books. my husband in this matter. Not only do I feel By CHARLES DICKENS. since last night, that I dare not confide to him the details of my projects; but also I feel that if I delay, there is danger of his giving warning, BOOK THE THIRD. THE TRACK OF A STORM. and then they might escape." CHAPTER XIV. THE KNITTING DONE. "That must never be," croaked Jacques IN that same juncture of time when the Fifty- Three; "no one must escape. We have not Two awaited their fate, Madame Defarge held half enough as it is. We ought to have six darkly ominous council with The Vengeance and score a day." Jacques Three of the Revolutionary Jury. Not "In a word," Madame Defarge went on, in the wine-shop did Madame Defarge confer "my husband has not my reason for pursuing with these ministers, but in the shed of the this family to annihilation, and I have not his wood-sawyer, erst a mender of roads. The reason for regarding this Doctor with any sensi- sawyer himself did not participate in the bility. I must act for myself, therefore. Come conference, but abided at a little distance, hither, little citizen." like an outer satellite who was not to speak The wood-sawyer, who held her in the re- until required, or to offer an opinion until in- spect, and himself in the submission, of mor- vited. -

A Tale of Two Cities

MACMILLAN READERS BEGINNER lEVEL CHARLES DIC KENS A Tale of Two Cities Retold by Stephen Colbourn Contents A Note About the Author 4 A Note About This Story 5 The People in This Story 7 1 To Dover 8 2 A Wine Shop in Paris 13 3 The Old Bailey 18 4 New Friends 24 5 The Aristocrat 26 6 A Wedding 31 7 Revolution 35 8 To Paris 39 9 An Enemy of the Repuhlic 43 10 Citizen Barsad 47 11 Doctor Manette's Letter 50 12 Sydney Carton's PlaIt 53 13 The Escape 55 14 The Guillotille 60 1 To Dover It was the year 1775. A coach was gOil1g from London to Dover. The road was wet and Inuddy. The horses pulled the heavy coach slowly. A man on a horse came along tIle road behind the coach. He was riding quickly. 'Stop!' shouted the rider. 'What do you want?' asked the coach driver. 'I have a message!' shouted the rider. He stopped l1is horse in front of the coach. The coach also stopped. 'The message is for Mr Jarvis Lorry,' said the rider. 8 A man looked out of the wi11dow of the coach. He was about sixty years old and l1e wore old ... fashioned clothes. He saw the rider and asked, 'What news do you bring, Jerry?' 'Do you know this man, sir?' asked the coach driver. 'There are robbers on this road.' 'I know him,' replied the old man. 'His name is Jerry Cruncher. He has come from my bank. Jerry Cruncher is a messenger, not a robber.' 'Here is a letter for you, Mr Lorry,' the messenger said. -

A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities Charles Dickens THE EMC MASTERPIECE SERIES Access Editions SERIES EDITOR Robert D. Sheperd EMC/Paradigm Publishing St. Paul, Minnesota Staff Credits: For EMC/Paradigm Publishing, St. Paul, Minnesota Laurie Skiba Eileen Slater Editor Editorial Consultant Shannon O’Donnell Taylor Jennifer J. Anderson Associate Editor Assistant Editor For Penobscot School Publishing, Inc., Danvers, Massachusetts Editorial Design and Production Robert D. Shepherd Charles Q. Bent President, Executive Editor Production Manager Christina E. Kolb Diane Castro Managing Editor Compositor Sara Hyry Janet Stebbings Editor Compositor Allyson Stanford Editor Sharon Salinger Copyeditor Marilyn Murphy Shepherd Editorial Advisor ISBN 0-8219-1651-3 Copyright © 1998 by EMC Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be adapted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permis- sion from the publishers. Published by EMC/Paradigm Publishing 875 Montreal Way St. Paul, Minnesota 55102 Printed in the United States of America. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 xxx 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 Table of Contents The Life and Works of Charles Dickens . v Time Line of Dickens’s Life . viii The Historical Context of A Tale of Two Cities............x Characters in A Tale of Two Cities ...................xv Echoes . xvii Illustration . xviii BOOK THE FIRST Chapter 1. 1 Chapter 2 . 4 Chapter 3 . 10 Chapter 4 . 15 Chapter 5 . 27 Chapter 6 . 39 BOOK THE SECOND Chapter 1. 52 Chapter 2 . 59 Chapter 3 . 66 Chapter 4 . 80 Chapter 5 . -

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens A Tale of Two Cities (1859) It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, Intro Horner it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness… Spring ‘ 06 This piece of fiction is based on many actual historical events. The Plot The action of A Tale of Two Cities takes place over a period of about eighteen years, beginning in 1775, and ending in 1793. Some of the story takes place earlier, as told in the flashbacks. It centers around the years leading up to French Revolution and culminates in the Jacobin Reign of Terror. It tells the story of two men, Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton, who look very alike but are entirely different in character. Darnay is a romantic descended from French aristocrats, while Carton is a cynical English barrister. The two are in love with the same woman, Lucie Manette: one will love her from afar and make a courageous sacrifice for her and the other will marry her. Lucie Manette Charles Darnay Sydney Carton In France after more than seventeen years of unjust imprisonment, Dr. Alexandre Manette (Lucie’s father) is released from the infamous Bastille, setting into motion this time spanning story of revenge and resurrection. Upon his release, Manette is sheltered and cared for by an old servant, Ernest Defarge, the wine vendor and his wife Madame Defarge. Madame Defarge The Setting London, England Paris, France Conflict In his dual focus on the French Revolution and the individual lives of his characters, Dickens draws many comparisons between the historical developments taking place and the characters’ triumphs and travails. -

Tale of Two Cities Manual

A Tale of Two Cities Charles Dickens Assessment Manual THE EMC MASTERPIECE SERIES Access Editions SERIES EDITOR Robert D. Shepherd EMC/P aradigm Publishing St. Paul, Minnesota Staff Credits: For EMC/Paradigm Publishing, St. Paul, Minnesota Laurie Skiba Eileen Slater Editor Editorial Consultant Shannon O’Donnell Taylor Jennifer J. Anderson Associate Editor Assistant Editor For Penobscot School Publishing, Inc., Danvers, Massachusetts Editorial Design and Production Robert D. Shepherd Charles Q. Bent President, Executive Editor Production Manager Christina E. Kolb Sara Day Managing Editor Art Director Kim Leahy Beaudet Tatiana Cicuto Editor Compositor Sara Hyry Editor Laurie A. Faria Associate Editor Sharon Salinger Copyeditor Marilyn Murphy Shepherd Editorial Consultant Assessment Advisory Board Dr. Jane Shoaf James Swanson Educational Consultant Educational Consultant Edenton, North Carolina Minneapolis, Minnesota Kendra Sisserson Facilitator, The Department of Education, The University of Chicago Chicago, Illinois ISBN 0–8219–1726–9 Copyright © 1998 by EMC Corporation All rights reserved. The assessment materials in this publication may be photocopied for classroom use only. No part of this publication may be adapted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit - ted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, with - out permission from the publisher. Published by EMC/Paradigm Publishing 875 Montreal Way St. Paul, Minnesota 55102 Printed in the United States of America. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 xxx 03 02 01 00 99 98 Table of Contents Notes to the Teacher . 2 ACCESS EDITION ANSWER KEY Answers for Book I, Chapters 1–6 . 6 Answers for Book II, Chapters 1–6 . -

Bibliographie a Tale of Two Cities

BIBLIOGRAPHIE A TALE OF TWO CITIES Bibliographie établie par Laurent Bury, Université Lyon 2 A Tale of Two Cities, manuscript olographe. Microfilm 26738 (Manuscripts of the Works of Charles Dickens. From the Forster Collection in the Victoria & Albert Museum. London). London: Micro Methods, 1969. The Bastille Prisoner, a Reading from A Tale of Two Cities, in Three Chapters, privately printed, 1866. Dickens condensed Book I of the novel into three scenes, had the speech published, but never actually delivered it. STOREY, Graham, BROWN, Margaret, and TILLOTSON, Kathleen, eds., The Letters of Charles Dickens, vol. 8 (1856-1858) and vol. 9 (1859-1861). The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995, 1997. COLLINS, Phillip, ed., Dickens: The Critical Heritage, 1971. ACKROYD, Peter, Dickens, London : Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990. Ouvrages exclusivement consacrés à A Tale of Two Cities : BECKWITH, Charles, Twentieth-Century Interpretations of A Tale of Two Cities, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1972 (ten essays) BLOOM, Harold, ed., Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, Modern Critical Interpretations, New York: Chelsea House, 1987. (Introduction by Bloom + eight essays) COTSELL, Michael A., Critical Essays on Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, Critical Essays on British Literature Series, New York: G.K. Hall, 1998 (Introduction by Cotsell + ten essays) GLANCY, Ruth, A Tale of Two Cities: An Annotated Bibliography, New York: Garland, 1993. A listing of editions, adaptatations, criticism, study guide and bibliographies related to the novel. GLANCY, Ruth, “A Tale of Two Cities”: Dickens’s Revolutionary Novel, Boston: Twayne, 1991. 135 pages, “a sourcebook for appreciating Dickens’s masterwork” ? GLANCY, Ruth, ed., Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, A Sourcebook.