Introduction: the Sense of Unending. Closing Charlotte Brontë's 'Emma'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Century British Detective Fiction

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 8-1-2014 Detecting Arguments: The Rhetoric of Evidence in Nineteenth-- Century British Detective Fiction Katherine Anders University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Repository Citation Anders, Katherine, "Detecting Arguments: The Rhetoric of Evidence in Nineteenth--Century British Detective Fiction" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2163. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/6456393 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DETECTING ARGUMENTS: THE RHETORIC OF EVIDENCE IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH DETECTIVE FICTION by Katherine Christie Anders Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts St. John’s College, Santa Fe 2003 Master of Library -

Book \\ the Anarchist a Story of To-Day (1894) by Richard

OOAURVZZUZ ^ The anarchist a story of to-day (1894) by Richard Henry Savage ~ eBook Th e anarch ist a story of to-day (1894) by Rich ard Henry Savage By Richard Henry Savage CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Paperback. Condition: New. This item is printed on demand. 186 pages. Dimensions: 11.0in. x 8.5in. x 0.4in.Richard Henry Savage (June 12, 1846 October 11, 1903) was an American military officer and author who wrote more than 40 books of adventure and mystery, based loosely on his own experiences. Savages eloquent, witty, dashing and daring life may have been the inspiration for the pulp novel character Doc Savage. In his youth in San Francisco, Savage studied engineering and law, and graduated from the United States Military Academy. After a few years of surveying work with the Army Corps of Engineers, Savage went to Rome as an envoy following which he sailed to Egypt to serve a stint with the Egyptian Army. Returning home, Savage was assigned to assess border disputes between the U. S. and Mexico, and he performed railroad survey work in Texas. In Washington D. C. , he courted and married a widowed noblewoman from Germany This item ships from La Vergne,TN. Paperback. READ ONLINE [ 6.17 MB ] Reviews It in one of my personal favorite book. Sure, it is engage in, continue to an amazing and interesting literature. I am quickly could possibly get a enjoyment of looking at a published book. -- Wellington Rosenbaum This is the very best publication i actually have read until now. It really is packed with knowledge and wisdom I am happy to let you know that this is the very best publication i actually have read in my very own existence and could be he greatest pdf for ever. -

Journal of Stevenson Studies

1 Journal of Stevenson Studies 2 3 Editors Dr Linda Dryden Professor Roderick Watson Reader in Cultural Studies English Studies Faculty of Art & Social Sciences University of Stirling Craighouse Stirling Napier University FK9 4La Edinburgh Scotland Scotland EH10 5LG Scotland Tel: 0131 455 6128 Tel: 01786 467500 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Contributions to future issues are warmly invited and should be sent to either of the editors listed above. The text should be submitted in MS WORD files in MHRA format. All contributions are subject to review by members of the Editorial Board. Published by The Centre for Scottish Studies University of Stirling © the contributors 2005 ISSN: 1744-3857 Printed and bound in the UK by Antony Rowe Ltd. Chippenham, Wiltshire. 4 Journal of Stevenson Studies Editorial Board Professor Richard Ambrosini Professor Gordon Hirsch Universita’ de Roma Tre Department of English Rome University of Minnesota Professor Stephen Arata Professor Katherine Linehan School of English Department of English University of Virginia Oberlin College, Ohio Professor Oliver Buckton Professor Barry Menikoff School of English Department of English Florida Atlantic University University of Hawaii at Manoa Dr Jenni Calder Professor Glenda Norquay National Museum of Scotland Department of English and Cultural History Professor Richard Dury Liverpool John Moores University of Bergamo University (Consultant Editor) Professor Marshall Walker Department of English The University of Waikato, NZ 5 Contents Editorial -

Stevensoniana; an Anecdotal Life and Appreciation of Robert Louis Stevenson, Ed. from the Writings of J.M. Barrie, S.R. Crocket

——; — ! 92 STEVENSONIANA VIII ISLAND DAYS TO TUSITALA IN VAILIMA^ Clearest voice in Britain's chorus, Tusitala Years ago, years four-and-twenty. Grey the cloudland drifted o'er us, When these ears first heard you talking, When these eyes first saw you smiling. Years of famine, years of plenty, Years of beckoning and beguiling. Years of yielding, shifting, baulking, ' When the good ship Clansman ' bore us Round the spits of Tobermory, Glens of Voulin like a vision. Crags of Knoidart, huge and hoary, We had laughed in light derision. Had they told us, told the daring Tusitala, What the years' pale hands were bearing, Years in stately dim division. II Now the skies are pure above you, Tusitala; Feather'd trees bow down to love you 1 This poem, addressed to Robert Louis Stevenson, reached him at Vailima three days before his death. It was the last piece of verse read by Stevenson, and it is the subject of the last letter he wrote on the last day of his life. The poem was read by Mr. Lloyd Osbourne at the funeral. It is here printed, by kind permission of the author, from Mr. Edmund Gosse's ' In Russet and Silver,' 1894, of which it was the dedication. After the Photo by] [./. Davis, Apia, Samoa STEVENSON AT VAILIMA [To face page i>'l ! ——— ! ISLAND DAYS 93 Perfum'd winds from shining waters Stir the sanguine-leav'd hibiscus That your kingdom's dusk-ey'd daughters Weave about their shining tresses ; Dew-fed guavas drop their viscous Honey at the sun's caresses, Where eternal summer blesses Your ethereal musky highlands ; Ah ! but does your heart remember, Tusitala, Westward in our Scotch September, Blue against the pale sun's ember, That low rim of faint long islands. -

On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins

早稲田大学国際教養学部 Waseda Global Forum No. 10 ( 2 0 1 4 )抜 刷 On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins Graham LAW ● Article ● On the Provenance of Two Late “American Stories” Attributed to Wilkie Collins Graham LAW Abstract The increasing availability of digital editions of historical newspapers has recently brought to light claims regarding the provenance of two tales first appearing in the American press in June and October 1889, respectively. These narratives, both with American settings, are there attributed to the British novelist, Wilkie Collins, who died on September 23, 1889. The claims regarding the first tale“, The Only Girl at Overview,” are limited to a single newspaper and can be quickly dismissed. In the case of the second tale“, One August Night in ’61,” since there is no clear-cut documentary evidence to settle the case, reaching a judgment concerning provenance involves sifting a good deal of circumstantial detail, extending well beyond literary contents. The various strands relate to the American novelist who reportedly“ wrote up” up the sketch, the journals publishing and the agency distributing it, the contemporary record of payments into and out of the author’s bank account, as well as the linguistic qualities of a letter allegedly written by him, and his physical and mental condition at the time in question. In the end, though, with the insurmountable difficulty concerning the timing of the alleged letter in relation to the author’s medical condition, the balance of evidence suggests that Wilkie Collins probably had no hand in the composition not only of“ The Only Girl at Overview” but also o“f One August Night in ’61.” Though this incident tells us little about the literary practices of the aging Wilkie Collins, it reveals a good deal about the material and ideological conditions prevailing in the American popular press towards the end of the nineteenth century. -

DETECTIVE NARRATIVE and the PROBLEM of ORIGINS in 19 CENTURY ENGLAND by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning Bachelor of Arts, West Chest

DETECTIVE NARRATIVE AND THE PROBLEM OF ORIGINS IN 19TH CENTURY ENGLAND by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning Bachelor of Arts, West Chester University, 1992 Master of Arts, West Virginia University, 1995 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The English Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH This dissertation was presented by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning It was defended on March 1st, 2006 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished University Service Professor, English Department, Film Studies, and the Cultural Studies Program James Seitz, Associate Professor, English Department Nancy Condee, Associate Professor, Slavic Languages and Literature and Director of the Program for Cultural Studies Dissertation Director: Colin MacCabe, Distinguished University Professor, English Literature, Film Studies, and the Cultural Studies Program ii Copyright © by Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning 2006 iii DETECTIVE NARRATIVE AND THE PROBLEM OF ORIGINS IN 19TH CENTURY ENGLAND Amy Rebecca Murray Twyning, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Working with Fredric Jameson’s understanding of genre as a “formal sedimentation” of an ideology, this study investigates the historicity of the detective narrative, what role it plays in bourgeois, capitalist culture, what ways it mediates historical processes, and what knowledge of these processes it preserves. I begin with the problem of the detective narrative’s origins. This is a complex and ultimately -

Wilkie Collins, a Biography

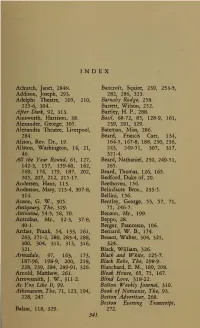

INDEX Achurch, Janet, 284n. Bancroft, Squire, 239, 253-5, Addison, Joseph, 293. 282, 286, 323. Adelphi Theatre, 205, 210, Barnaby Rudge, 258. 225-6, 304. Barrett, Wilson, 252. After Dark, 92, 313. Bartley, H. P., 288. Ainsworth, Harrison, 38. Basil, 68-72, 85, 128-9, 161, Alexander, George, 305. 239, 291, 329. Alexandra Theatre, Liverpool, Bateman, Miss, 286. 284. Beard, Francis Carr, 134, Alison, Rev. Dr., 19. 164-5, 167-8, 188, 230, 236, Allston, Washington, 14, 21, 243, 249-51, 307, 317, 46. 321-4. All the Year Round, 61, 127, Beard, Nathaniel, 230, 249-51, 142-3, 157, 159-60, 162, 265. 169, 174, 179, 187, 202, Beard, Thomas, 126, 165. 205, 207, 212, 215-17. Bedford, Duke of, 20. Andersen, Hans, 113. Beethoven, 156. Anderson, Mary, 213-4, 307-8, Belinfaute Bros., 233-5. 314. Bellini, 156. Anson, G. W., 305. Bentley, George, 53, 57, 71, Antiquary, The, 329. 75, 246-7. Antonina, 54-5, 58, 70. Benzon, Mr., 199. Antrobus, Mr., 32-3, 37-8, Beppo, 28. 40-1. Berger, Francesco, 106. Archer, Frank, 54, 133, 261, Bernard, W. B., 174. 263, 271-2, 280, 283-4, 288, Besant, Walter, 304, 321, 300, 304, 311, 313, 316, 324. 321. Black, William, 326. Armadale, 97, 163, 173, Black and White, 225-7. 187-96, 198-9, 200, 218, Black Robe, The, 298-9. 228, 239, 284, 289-91, 326. Blanchard, E. M., 189, 208. Arnold, Matthew, 261. Bleak House, 65, 75, 167. Arrowsmith, J. W., 311-2. Blind Love, 318-22. As You Like It, 99. Bolton Weekly Journal, 310. -

Classy City: Residential Realms of the Bay Region

Classy City: Residential Realms of the Bay Region Richard Walker Department of Geography University of California Berkeley 94720 USA On-line version Revised 2002 Previous published version: Landscape and city life: four ecologies of residence in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ecumene . 2(1), 1995, pp. 33-64. (Includes photos & maps) ANYONE MAY DOWNLOAD AND USE THIS PAPER WITH THE USUAL COURTESY OF CITATION. COPYRIGHT 2004. The residential areas occupy the largest swath of the built-up portion of cities, and therefore catch the eye of the beholder above all else. Houses, houses, everywhere. Big houses, little houses, apartment houses; sterile new tract houses, picturesque Victorian houses, snug little stucco homes; gargantuan manor houses, houses tucked into leafy hillsides, and clusters of town houses. Such residential zones establish the basic tone of urban life in the metropolis. By looking at residential landscapes around the city, one can begin to capture the character of the place and its people. We can mark out five residential landscapes in the Bay Area. The oldest is the 19th century Victorian townhouse realm. The most extensive is the vast domain of single-family homes in the suburbia of the 20th century. The grandest is the carefully hidden ostentation of the rich in their estates and manor houses. The most telling for the cultural tone of the region is a middle class suburbia of a peculiar sort: the ecotopian middle landscape. The most vital, yet neglected, realms are the hotel and apartment districts, where life spills out on the streets. More than just an assemblage of buildings and styles, the character of these urban realms reflects the occupants and their class origins, the economics and organization of home- building, and larger social purposes and planning. -

The Moonstone

The Moonstone Wilkie Collins Retold by David Wharry Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn potter Contents Page Introduction 4 Taken From an Old Family Letter 5 Part 1 The Loss of the Diamond 7 Chapter 1 A Record of the Facts 7 Chapter 2 Three Indian Men 8 Chapter 3 The Will 9 Chapter 4 A Shadow 13 Chapter 5 Rivals 14 Chapter 6 The Moonstone 17 Chapter 7 The Indians Return 18 Chapter 8 The Theft 21 Chapter 9 Sergeant Cuff Arrives 26 Chapter 10 The Search Begins 29 Chapter 11 Rosanna 30 Chapter 12 Rachel's Decision 34 Chapter 13 A Letter 36 Chapter 14 The Shivering Sands 39 Chapter 15 To London 44 Part 2 The Discovery of the Truth 46 First Narrative 46 Chapter 1 A Strange Mistake 46 Chapter 2 Rumours and Reputations 49 Chapter 3 Placing the Books 54 Chapter 4 A Silent Listener 56 Chapter 5 Brighton 59 Second Narrative 65 Chapter 1 Money-Lending 65 Chapter 2 Next June 67 2 Third Narrative 69 Chapter 1 Franklin's Return 69 Chapter 2 Instructions 71 Chapter 3 Rosanna's Letter 73 Chapter 4 Return to London 76 Chapter 5 Witness 78 Chapter 6 Investigating 82 Chapter 7 Lost Memory 85 Chapter 8 Opium 87 Fourth Narrative 90 Fifth Narrative 94 Sixth Narrative 100 3 Introduction 'Look, Gabriel!' cried Miss Rachel, flashing the jewel in the sunlight. It was as large as a bird's egg, the colour of the harvest moon, a deep yellow that sucked your eyes into it so you saw nothing else. -

Infirm Soldiers in the Cuban War of Theodore Roosevelt and Richard Harding Davis”

David Kramer “Infirm Soldiers in the Cuban War of Theodore Roosevelt and Richard Harding Davis” George Schwartz was thought to be one of the few untouched by the explosion of the Maine in the Havana Harbor. Schwartz said that he was fine. However, three weeks later in Key West, he began to complain of not being able to sleep. One of the four other survivors [in Key West] said of Schwartz, “Yes, sir, Schwartz is gone, and he knows it. I don’t know what’s the matter with him and he don’t know. But he’s hoisted his Blue Peter and is paying out his line.” After his removal to the Marine Hospital in Brooklyn, doctors said that Schwartz’s nervous system had been completely damaged when he was blown from the deck of the Maine. —from press reports in early April 1898, shortly before the United States officially declared War on Spain. n August 11th 1898 at a Central Park lawn party organized by the Women’s Patriotic Relief Association, 6,000 New Yorkers gathered to greet invalided sol- diers and sailors returningO from Cuba following America’s victory. Despite the men’s infirmities, each gave his autograph to those in attendance. A stirring letter was read from Richmond Hobson, the newly anointed hero of Santiago Bay. Each soldier and sailor received a facsimile lithograph copy of the letter as a souvenir.1 Twenty years later, the sight of crippled and psychologically traumatized soldiers returning from France would shake the ideals of Victorian England, and to a lesser degree, the United States. -

Catalogue of the Original Manuscripts, by Charles Dickens and Wilkie

UC-NRLF B 3 55D 151 1: '-» n ]y>$i^

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church.