Con Music Rare Book THESIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pomegranate Cycle

The Pomegranate Cycle: Reconfiguring opera through performance, technology & composition By Eve Elizabeth Klein Bachelor of Arts Honours (Music), Macquarie University, Sydney A PhD Submission for the Department of Music and Sound Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia 2011 ______________ Keywords Music. Opera. Women. Feminism. Composition. Technology. Sound Recording. Music Technology. Voice. Opera Singing. Vocal Pedagogy. The Pomegranate Cycle. Postmodernism. Classical Music. Musical Works. Virtual Orchestras. Persephone. Demeter. The Rape of Persephone. Nineteenth Century Music. Musical Canons. Repertory Opera. Opera & Violence. Opera & Rape. Opera & Death. Operatic Narratives. Postclassical Music. Electronica Opera. Popular Music & Opera. Experimental Opera. Feminist Musicology. Women & Composition. Contemporary Opera. Multimedia Opera. DIY. DIY & Music. DIY & Opera. Author’s Note Part of Chapter 7 has been previously published in: Klein, E., 2010. "Self-made CD: Texture and Narrative in Small-Run DIY CD Production". In Ø. Vågnes & A. Grønstad, eds. Coverscaping: Discovering Album Aesthetics. Museum Tusculanum Press. 2 Abstract The Pomegranate Cycle is a practice-led enquiry consisting of a creative work and an exegesis. This project investigates the potential of self-directed, technologically mediated composition as a means of reconfiguring gender stereotypes within the operatic tradition. This practice confronts two primary stereotypes: the positioning of female performing bodies within narratives of violence and the absence of women from authorial roles that construct and regulate the operatic tradition. The Pomegranate Cycle redresses these stereotypes by presenting a new narrative trajectory of healing for its central character, and by placing the singer inside the role of composer and producer. During the twentieth and early twenty-first century, operatic and classical music institutions have resisted incorporating works of living composers into their repertory. -

BRUCE CALE, SERIALISM and the LYDIAN CONCEPT by Eric Myers* ______

BRUCE CALE, SERIALISM AND THE LYDIAN CONCEPT by Eric Myers* ____________________________________________________ [This article appeared in the October, 1985 edition of APRA, the magazine of the Australasian Performing Right Association.] hen the Australia** Music Centre's film on Australian composers Notes On A Landscape came out in 1980, it was apparent that most of the ten W composers included, picked themselves: Don Banks, Anne Boyd, Colin Brumby, Barry Conyngham, Keith Humble, Elena Kats, Graeme Koehne, Richard Meale, Peter Sculthorpe. In addition to them, there was one composer who, on the face of it, might not have been regarded as such an automatic choice: Bruce Cale. Bruce Cale on the verandah of his house in the Blue Mountains, with his dog Muffin… PHOTO CREDIT MARGARET SULLIVAN __________________________________________________________________ *When this was written in October, 1985, Eric Myers was editor of the Australian Jazz Magazine, and writing jazz reviews for The Australian. **Australia Music Centre was at the time the correct spelling. Sometime later ‘Australia’ was changed to ‘Australian’. 1 After all, he was principally known as a jazz composer and performer, and when the film was planned, had been back in Australia only two years, following 13 years in Britain and the United States. On the other hand, there were some eyebrows raised in the Australian jazz world that Cale was "the only jazz composer" included in the film. But those who were aware of Cale's work knew that he had been included because of his orchestral writing as well as his jazz composition; his work had certainly emerged from jazz but, in a highly individual way, he was seeking to merge jazz and classical traditions. -

Bankks Butterley Mealee Werder

BANKS BUTTERLEY MEALE WERDER Like so many string quartets, the maestoso’, but the music is hard and changes texture in a more flexible manner. pieces recorded here engage with the concrete. These blocks of sound vary The moments when the quartet comes relationship of the ensemble’s four in length – the rhythmic notation is together in rhythmically regular music are players. Some of the works continue flexible – and the performers decide the striking and climactic. the tradition of cohesive playing, and length of each block in the moment of The second seating configuration, ‘far others question that aspect of the genre’s performance. The effect is that both the away’, begins with, is sustained by, and history. start and end of notes are highly charged. ends with clouds of harmonics. If the first In live performances of Meale’s String In some cases Meale further heightens section retains some hint of progression Quartet No. 1 his direct challenge to this idea, and the fourth chord, marked in its procession of variations, this section the performers is plain to see, for the dolce, ends with a left-hand pizzicato as is totally still. Through the harmonics piece is in two sections: in the first the the bow leaves the string. The abruptness Meale traces lines of pitches that lead us performers sit in the usual configuration, of the gesture is not at all what one might across the stage, but nowhere else. These and for the second section the performers think of as dolce, but this is a piece that three sequences are labelled ‘Tropes’. -

Ferienkurse Für Internationale Neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946

Ferienkurse für internationale neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946 Seminare der Fachgruppen: Dirigieren Carl Mathieu Lange Komposition Wolfgang Fortner (Hauptkurs) Hermann Heiß (Zusatzkurs) Kammermusik Fritz Straub (Hauptkurs) Kurt Redel (Zusatzkurs) Klavier Georg Kuhlmann (auch Zusatzkurs Kammermusik) Gesang Elisabeth Delseit Henny Wolff (Zusatzkurs) Violine Günter Kehr Opernregie Bruno Heyn Walter Jockisch Musikkritik Fred Hamel Gemeinsame Veranstaltungen und Vorträge: Den zweiten Teil dieser Übersicht bilden die Veranstaltungen der „Internationalen zeitgenössischen Musiktage“ (22.9.-29.9.), die zum Abschluß der Ferienkurse von der Stadt Darmstadt in Verbindung mit dem Landestheater Darmstadt, der „Neuen Darmstädter Sezession“ und dem Süddeutschen Rundfunk, Radio Frankfurt, durchgeführt wurden. Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit So., 25.8. Erste Schloßhof-Serenade Kst., 11.00 Ansprache: Bürgermeister Julius Reiber Conrad Beck Serenade für Flöte, Klarinette und Streichorchester des Landes- Streichorchester (1935) theaters Darmstadt, Ltg.: Carl Wolfgang Fortner Konzert für Streichorchester Mathieu Lange (1933) Solisten: Kurt Redel (Fl.), Michael Mayer (Klar.) Kst., 16.00 Erstes Schloß-Konzert mit neuer Kammermusik Ansprachen: Kultusminister F. Schramm, Oberbürger- meister Ludwig Metzger Lehrkräfte der Ferienkurse: Paul Hindemith Sonate für Klavier vierhändig Heinz Schröter, Georg Kuhl- (1938) mann (Kl.) Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit Hermann Heiß Sonate für Flöte und Klavier Kurt Redel (Fl.), Hermann Heiß (1944-45) (Kl.) Heinz Schröter Altdeutsches Liederspiel , II. Teil, Elisabeth Delseit (Sopr.), Heinz op. 4 Nr. 4-6 (1936-37) Schröter (Kl.) Wolfgang Fortner Sonatina für Klavier (1934) Georg Kuhlmann (Kl.) Igor Strawinsky Duo concertant für Violine und Günter Kehr (Vl.), Heinz Schrö- Klavier (1931-32) ter (Kl.) Mo., 26.8. Komponisten-Selbstporträts I: Helmut Degen Kst., 16.00 Kst., 19.00 Einführung zum Klavierabend Georg Kuhlmann Di., 27.8. -

Roslyn Dunlop, Clarinet

Ithaca College Digital Commons IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-8-2001 Guest Artist Recital: Roslyn Dunlop, clarinet Roslyn Dunlop Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Dunlop, Roslyn, "Guest Artist Recital: Roslyn Dunlop, clarinet" (2001). All Concert & Recital Programs. 7684. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/7684 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons IC. GUEST ARTIST RECITAL Roslyn Dunlop, clarinet 25Measures Elena Kats-Chemin Trio Don Banks NRG (1996) Gerard Brophy Instant Winners Barney Childs Frenzy and Folly, Fire and Joy Graham Hair for solo clarinet Martin Wesley-Smith INTERMISSION Every Tune Phill Niblock You can take it anywhere! Judy Bailey New Work Stephen Ingham Recital Hall Monday, October 8, 2001 8:15 p.m. Roslyn Dunlop has earned a reputation as a specialist of new music for the clarinet, bass clarinet, and Eb clarinet. She is a keen promoter of her countryman's music and to this end has performed Australian composers works en every continent of the world. She graduated from ~he Sydney Conservatorium of Music with a Bachelor of Music in 1983; her teacher was Gabor Reeves. Subsequently she undertook post- graduate studies at Michigan State University where she studied clarinet with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Since 1986 she has performed regularly as soloist and chamber musician. Currently a member of Charisma and Touchbass, Ms. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1996, No.5

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: ^ Primakov travels to Kyiv to fay groundwork for Yeltsin visit - page 3. e Radio Canada International saved by Cabinet shuffle - page 4. 9 Washington Post correspondent shares impressions of Ukraine - page 5. THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIV No. 5 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 1996 S1.2542 in Ukraine Ukraine's coal miners stage strike Parliament cancels moratorium to demand payment of back wages on adoptions, sets procedures by Marta Kolomayets during this harsh winter - amidst condi by Marta Kolomayets children adopted by foreigners through Kyiv Press Bureau tions of gas and oil shortages - and Kyiv Press Bureau Ukrainian consular services until they should be funded immediately from the turn 18 and forbids any commercial for KYIV - Despite warnings of mass state budget. KYIV - The Parliament on January 30 eign intermediaries to take part in the strikes involving coal mines throughout lifted a moratorium on adoption of As The Weekly was going to press, adoption process. Ukraine, Interfax-Ukraine reported that Ukrainian children by foreigners and Coal Industry Minister Serhiy Polyakov The law, which takes effect April 1, as of late Thursday evening, February I, voted to establish a new centralized mon had been dispatched to discuss an agree will closely scrutinize the fate and workers from only 86 mines out of 227 ment with strike leaders. According to itoring agency that will require all adop whereabouts of Ukraine's most precious had decided to walk out. They are Interfax-Ukraine, the Cabinet of Ministers tions in Ukraine to pass through, the resource - its children. -

Forbidden Colours

476 3220 GERARD BROPHY forbidden colours TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Almost every Australian composer born literature, made Sculthorpe (vernacular) and between the end of the First World War and the Meale (international) obvious first generation end of the baby-boomer generation owes even leaders. The upheavals of 1968, and the social their most modest reputation to a half-truth: that revolution that followed in their wake, helped it was only in the early 1960s that our post- convince their students that their Australian colonial music culture caught up with the world identity should derive from looking both inward and produced its first distinctive national school and outward. But to Brophy in the next Gerard Brophy b. 1953 of composers. In press columns, and in his generation, the first to grow up in a multicultural 1967 book Australia’s Music: Themes of a New globalising environment, such a self-conscious 1 The Republic of Dreams 8’32 Society, Roger Covell gave culturally literate pursuit of Australianness came to seem not only Genevieve Lang harp, Philip South darabukka Australians their first reliable list of composers creatively irrelevant, but a failure of imagination. worth following, most of them contemporary. For Brophy, what would once have been Mantras [14’36] And what Donald Peart dubbed ‘The Australian described as a ‘cosmopolitan’ outlook comes 2 Mantra I 3’42 Avant-garde’ owed as much to frustrations of naturally to a contemporary Australian artist. 3 Mantra II 3’10 journalists, academics and conductors with the 4 Mantra III 7’44 deadening local cult of ‘musical cobwebs’ as it Born into an ‘ordinary Anglo-Irish family’ in did to the talents of the new movement’s Sydney’s eastern suburbs, Brophy grew up in 5 Maracatú 11’11 anointed leaders, Peter Sculthorpe, Richard country Coonamble. -

Don Banks, Australian Composer

Don Banks, Australian Composer: Eleven Sketches Graham Hair Southern Voices ISBN 1–876463–09–0 First published in 2007 by Southern Voices 38 Diamond Street Amaroo, ACT 2914 AUSTRALIA Southern Voices Editorial Board: Professor Graham Hair, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom Ms Robyn Holmes, Curator of Music, National Library of Australia Professor Margaret Kartomi, Monash University Dr Jonathan Powles, Australian National University Dr Martin Wesley-Smith, formerly Senior Lecturer, Sydney Conservatorium of Music Distributed by The Australian Music Centre, trading asSounds Australian PO Box N690 The Rocks Sydney, NSW 2000 AUSTRALIA tel +(612) 9247 - 4677 fax +(612) 9241 - 2873 email [email protected] website www.amcoz.com.au/amc Copyright © Graham Hair, 2007 This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Enquiries to be made to the publisher. Copying for educational purposes Where copies of part or the whole of the book are made under section 53B or 53D of the Act, the law requires that records of such copying be kept. In such cases the copyright owner is entitled to claim payment. ISBN 1–876463–09–0 Printed in Australia by QPrint Pty Ltd, Canberra City, ACT 2600 and in the UK by Garthland Design and Print, Glasgow, G51 2RL Acknowledgements Extracts from the scores by Don Banks are reproduced by permission of Mrs Val Banks and Mrs Karen Sutcliffe. -

LARES Lexicon Acoustic Reverberance Enhancement System

LARES Lexicon Acoustic Reverberance Enhancement System exicon How LARES can Help Meet the Objectives of Good Acoustical Design". Sound Reinforcement Reinforcing Early Reflections In this application LARES principles yield an in The perceived loudness of a sound in a hall depends crease in gain-before-feedback of 6 -18 dB. The both on the loudness of the direct sound and on the amount of improvement depends on the number of amount of early reflected energy which adds to the microphones, loudspeaker channels, and number direct sound. The level of the first few strong of Lexicon's Advanced DSP processors. For ex reflections is determined primarily by the hall ge ample, the increase is 15 dB with two microphones, ometry. Careful placement of reflecting surfaces in four loudspeaker channels, and one Lexicon 480L the stage, ceiling and side walls can increase this Advanced DSP. With two processors and eight level somewhat by directing sound energy to the loudspeaker channels, the improvement is 18 dB. audience. However, the energy directed to the audience by walls or reflectors is generally ab With such a large increase in gain before feedback sorbed, and is not available to create additional level far fewer microphones need to be employed to or later reverberation. For this and many other reinforce any performance, and the reinforcement is reasons, the total amount of reflected energy de hard to distinguish from the natural response of the pends primarily on the amount of absorption in the hall. This type of reinforcement is ideal for boosting hall, which in most halls is proportional to the seating a weak vocalist or chorus in a show, improving stage area. -

A Study of Compositional Techniques Used in the Fusion of Art Music With

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright A Study of Compositional Techniques Used in the Fusion of Art Music with Jazz and Popular Music Nadia Burgess Volume 1 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2014 Declaration I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. -

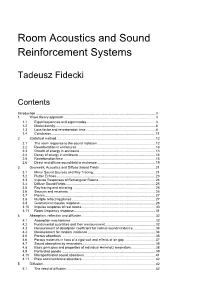

Room Acoustics and Sound Reinforcement Systems

Room Acoustics and Sound Reinforcement Systems Tadeusz Fidecki Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Wave theory approach ................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Eigenfrequencies and eigenmodes .......................................................................... 3 1.2 Modal density ............................................................................................................ 8 1.3 Loss factor and reverberation time ........................................................................... 8 1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................................ 11 2. Statistical method ........................................................................................................... 12 2.1 The room response to the sound radiation ............................................................... 12 2.2 Reverberation in enclosures ..................................................................................... 13 2.3 Growth of energy in enclosure .................................................................................. 13 2.4 Decay of energy in enclosure ................................................................................... 14 2.5 Reverberation time .................................................................................................. -

DON BANKS Interviewed by Mike Williams

DON BANKS Interviewed by Mike Williams* _________________________________________________________ [This interview was published in Mike Williams’ 1981 book The Australian Jazz Explosion.] Don Banks: his Dad brought home a record of Teddy Wilson playing A-Tisket, A- Tasket. Don had never heard piano playing like that… he was hooked from then on… PHOTO CREDIT JANE MARCH Mike Williams writes: Don Banks, who died in August, 1980, was an internationally respected composer of ‘serious’ music, with a considerable number of coveted awards to his credit. He had received commissions to compose for some of Europe’s most prestigious musical occasions. In the late 1940s he was also in the forefront of the modern jazz revolution in Australia, Melbourne’s most influential pianist and arranger in the new idiom. From 1950 until the early 1970s he was overseas, at first studying, then following his career as a composer. But he never lost his links with jazz. With Margaret Sutherland he formed the Australian Musical Association in London, he was chairman of the Society for the Promotion of New Music and an executive member of the British Society for Electronic Music. But he was also one of the two patrons for the London Jazz Centre Society, now a powerful promotional organisation in Britain (the other patron was John Dankworth). In 1 1973, after he had returned permanently to Australia to head the Composition Department at the Canberra School of Music, he was appointed the first Chairman of the Music Board of the fledgling Australia Council. It was largely due to him that the Council first channelled funds into the development of jazz in Australia and he was inspirational in founding the Jazz Action Society movement.