Australian Chamber Music with Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRUCE CALE, SERIALISM and the LYDIAN CONCEPT by Eric Myers* ______

BRUCE CALE, SERIALISM AND THE LYDIAN CONCEPT by Eric Myers* ____________________________________________________ [This article appeared in the October, 1985 edition of APRA, the magazine of the Australasian Performing Right Association.] hen the Australia** Music Centre's film on Australian composers Notes On A Landscape came out in 1980, it was apparent that most of the ten W composers included, picked themselves: Don Banks, Anne Boyd, Colin Brumby, Barry Conyngham, Keith Humble, Elena Kats, Graeme Koehne, Richard Meale, Peter Sculthorpe. In addition to them, there was one composer who, on the face of it, might not have been regarded as such an automatic choice: Bruce Cale. Bruce Cale on the verandah of his house in the Blue Mountains, with his dog Muffin… PHOTO CREDIT MARGARET SULLIVAN __________________________________________________________________ *When this was written in October, 1985, Eric Myers was editor of the Australian Jazz Magazine, and writing jazz reviews for The Australian. **Australia Music Centre was at the time the correct spelling. Sometime later ‘Australia’ was changed to ‘Australian’. 1 After all, he was principally known as a jazz composer and performer, and when the film was planned, had been back in Australia only two years, following 13 years in Britain and the United States. On the other hand, there were some eyebrows raised in the Australian jazz world that Cale was "the only jazz composer" included in the film. But those who were aware of Cale's work knew that he had been included because of his orchestral writing as well as his jazz composition; his work had certainly emerged from jazz but, in a highly individual way, he was seeking to merge jazz and classical traditions. -

Bankks Butterley Mealee Werder

BANKS BUTTERLEY MEALE WERDER Like so many string quartets, the maestoso’, but the music is hard and changes texture in a more flexible manner. pieces recorded here engage with the concrete. These blocks of sound vary The moments when the quartet comes relationship of the ensemble’s four in length – the rhythmic notation is together in rhythmically regular music are players. Some of the works continue flexible – and the performers decide the striking and climactic. the tradition of cohesive playing, and length of each block in the moment of The second seating configuration, ‘far others question that aspect of the genre’s performance. The effect is that both the away’, begins with, is sustained by, and history. start and end of notes are highly charged. ends with clouds of harmonics. If the first In live performances of Meale’s String In some cases Meale further heightens section retains some hint of progression Quartet No. 1 his direct challenge to this idea, and the fourth chord, marked in its procession of variations, this section the performers is plain to see, for the dolce, ends with a left-hand pizzicato as is totally still. Through the harmonics piece is in two sections: in the first the the bow leaves the string. The abruptness Meale traces lines of pitches that lead us performers sit in the usual configuration, of the gesture is not at all what one might across the stage, but nowhere else. These and for the second section the performers think of as dolce, but this is a piece that three sequences are labelled ‘Tropes’. -

Jerzy Kozlowski Michael Kieran Harvey New Song Cycles

ASTRA 2010 6 pm, Saturday 19 June, 6 pm, Sunday 20 June ELEVENTH HOUR THEATRE Fitzroy, Melbourne Jerzy Kozlowski bass Michael Kieran Harvey piano new song cycles: Michael Bertram at 75, Lawrence Whiffin at 80 Michael Bertram UNDERGROUND SONGS (2008) first performance Everyone Sang (Siegfried Sassoon) Trail all your pikes ( Anne Finch) He wishes for the Cloths of Heaven ( W.B.Yeats) I saw a peacock with a fiery tail (Anon. 17thC) Lawrence Whiffin PIANO SONATA NO.1 (1961/2006) I. Allegro molto II. Andante – Theme and Variations I N T E R V A L Lawrence Whiffin TIME STEALS SOFTER (2009) poems by George Genovese first performance Time Steals Softer (I) Walking Patriots Two Lives A Poet's Office Medi-Whinge 2004 Time Steals Softer (II) UNDERGROUND SONGS / TIME STEALS SOFTER … Sets of songs provoke a special relation between music and poetry – the choice and the order of poems has a formative influence on the trajectory and characters of the music that enters into their space. In the two new song cycles of this concert another influence is at work as well: the voice of the singer himself. Jerzy Kozlowski’s singing has become a well-known part of Astra programs over a long time and a wide terrain, from mediaeval music and Monteverdi to Reger (Eichendorrf), Busoni (Faust), Elisabeth Lutyens (Auden) and Helen Gifford (Shakespeare). Specifically, his two previous Astra solo recitals performing the late song-cycles of Shostakovich (Michelangelo and Dostoyevsky) made a remarkable impression for the possibilities of the medium of bass voice and piano, and stimulated both Michael Bertram and Lawrence Whiffin to compose new sets of songs particularly for him. -

The Australian Symphony of the 1950S: a Preliminary Survey

The Australian Symphony of the 1950s: A Preliminary survey Introduction The period of the 1950s was arguably Australia’s ‘Symphonic decade’. In 1951 alone, 36 Australian symphonies were entries in the Commonwealth Jubilee Symphony Competition. This music is largely unknown today. Except for six of the Alfred Hill symphonies, arguably the least representative of Australian composition during the 1950s and a short Sinfonietta- like piece by Peggy Glanville-Hicks, the Sinfonia da Pacifica, no Australian symphony of the period is in any current recording catalogue, or published in score. No major study or thesis to date has explored the Australian symphony output of the 1950s. Is the neglect of this large repertory justified? Writing in 1972, James Murdoch made the following assessment of some of the major Australian composers of the 1950s. Generally speaking, the works of the older composers have been underestimated. Hughes, Hanson, Le Gallienne and Sutherland, were composing works at least equal to those of the minor English composers who established sizeable reputations in their own country.i This positive evaluation highlights the present state of neglect towards Australian music of the period. Whereas recent recordings and scores of many second-ranking British and American composers from the period 1930-1960 exist, almost none of the larger works of Australians Robert Hughes, Raymond Hanson, Dorian Le Gallienne and their contemporaries are heard today. This essay has three aims: firstly, to show how extensive symphonic composition was in Australia during the 1950s, secondly to highlight the achievement of the main figures in this movement and thirdly, to advocate the restoration and revival of this repertory. -

Ferienkurse Für Internationale Neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946

Ferienkurse für internationale neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946 Seminare der Fachgruppen: Dirigieren Carl Mathieu Lange Komposition Wolfgang Fortner (Hauptkurs) Hermann Heiß (Zusatzkurs) Kammermusik Fritz Straub (Hauptkurs) Kurt Redel (Zusatzkurs) Klavier Georg Kuhlmann (auch Zusatzkurs Kammermusik) Gesang Elisabeth Delseit Henny Wolff (Zusatzkurs) Violine Günter Kehr Opernregie Bruno Heyn Walter Jockisch Musikkritik Fred Hamel Gemeinsame Veranstaltungen und Vorträge: Den zweiten Teil dieser Übersicht bilden die Veranstaltungen der „Internationalen zeitgenössischen Musiktage“ (22.9.-29.9.), die zum Abschluß der Ferienkurse von der Stadt Darmstadt in Verbindung mit dem Landestheater Darmstadt, der „Neuen Darmstädter Sezession“ und dem Süddeutschen Rundfunk, Radio Frankfurt, durchgeführt wurden. Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit So., 25.8. Erste Schloßhof-Serenade Kst., 11.00 Ansprache: Bürgermeister Julius Reiber Conrad Beck Serenade für Flöte, Klarinette und Streichorchester des Landes- Streichorchester (1935) theaters Darmstadt, Ltg.: Carl Wolfgang Fortner Konzert für Streichorchester Mathieu Lange (1933) Solisten: Kurt Redel (Fl.), Michael Mayer (Klar.) Kst., 16.00 Erstes Schloß-Konzert mit neuer Kammermusik Ansprachen: Kultusminister F. Schramm, Oberbürger- meister Ludwig Metzger Lehrkräfte der Ferienkurse: Paul Hindemith Sonate für Klavier vierhändig Heinz Schröter, Georg Kuhl- (1938) mann (Kl.) Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit Hermann Heiß Sonate für Flöte und Klavier Kurt Redel (Fl.), Hermann Heiß (1944-45) (Kl.) Heinz Schröter Altdeutsches Liederspiel , II. Teil, Elisabeth Delseit (Sopr.), Heinz op. 4 Nr. 4-6 (1936-37) Schröter (Kl.) Wolfgang Fortner Sonatina für Klavier (1934) Georg Kuhlmann (Kl.) Igor Strawinsky Duo concertant für Violine und Günter Kehr (Vl.), Heinz Schrö- Klavier (1931-32) ter (Kl.) Mo., 26.8. Komponisten-Selbstporträts I: Helmut Degen Kst., 16.00 Kst., 19.00 Einführung zum Klavierabend Georg Kuhlmann Di., 27.8. -

Roslyn Dunlop, Clarinet

Ithaca College Digital Commons IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-8-2001 Guest Artist Recital: Roslyn Dunlop, clarinet Roslyn Dunlop Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Dunlop, Roslyn, "Guest Artist Recital: Roslyn Dunlop, clarinet" (2001). All Concert & Recital Programs. 7684. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/7684 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons IC. GUEST ARTIST RECITAL Roslyn Dunlop, clarinet 25Measures Elena Kats-Chemin Trio Don Banks NRG (1996) Gerard Brophy Instant Winners Barney Childs Frenzy and Folly, Fire and Joy Graham Hair for solo clarinet Martin Wesley-Smith INTERMISSION Every Tune Phill Niblock You can take it anywhere! Judy Bailey New Work Stephen Ingham Recital Hall Monday, October 8, 2001 8:15 p.m. Roslyn Dunlop has earned a reputation as a specialist of new music for the clarinet, bass clarinet, and Eb clarinet. She is a keen promoter of her countryman's music and to this end has performed Australian composers works en every continent of the world. She graduated from ~he Sydney Conservatorium of Music with a Bachelor of Music in 1983; her teacher was Gabor Reeves. Subsequently she undertook post- graduate studies at Michigan State University where she studied clarinet with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Since 1986 she has performed regularly as soloist and chamber musician. Currently a member of Charisma and Touchbass, Ms. -

Dogs in Space Music Credits

THE BANDS 'Dogs in Space' 'Whirlywirld' Edward Clayton-Jones Arnie Hanna Michael Hutchence David Hoy Chuck Meo Johnn Murphy Nique Needles Ollie Olsen Glenys Osborne 'Too Fat To Fit Through the Door' 'Thrush and the C...S' Marcus Bergner Denise Grant Marie Hoy Marie Hoy John Murphy Danila Stirpe James Rogers Jules Taylor Ollie Olsen 'Primitive Calculators' 'Marie Hoy & Friends' Terry Dooley Marie Hoy Denise Grant Loki Stuart Grant Tim Millikan David Light John Murphy Ollie Olsen Musical Director Ollie Olsen Strange Noises John Murphy Music Research Bruce Milne Music Recorded at Richmond Recorders by Tony Cohen Music mixed at A.A.V. by Ross Cockle "Rooms for the Memory" Remixed by Nick Launay 'Shivers Video Clip' directed by Paul Goldman and Evan English 3RRR I.D. Written & Produced by Martin Armiger Sung by Jane Clifton THE MUSIC 'Dog Food' Performed by Iggy Pop, James Osterman Music (BMI), Administered by Bug Music Group, (P) 1980, Arista Records Inc., Courtesy of Arista Records 'Frankie Teardrop' Courtesy of Stamphyl Revega 'Dogs in Space' Written by Sam Sejavka and Mike Lewis 'Win/Lose' Written by Ollie Olsen, Performed by Whirlywirld, Courtesy of Missing Link Records 'True Love' Performed by The Marching Girls, Courtesy of Missing Link Records 'Sky Saw' Written by Brian Eno, Courtesy of E.G. Records Ltd. and E.G. Music Ltd. 'Skullbrains' Written by Marcus Bergner and Marie Hoy 'Shivers' Written by Roland S. Howard, Performed by Boys Next Door Courtesy of Mushroom Records 'Diseases' Composed by Thrush and The C...s 'Pumping Ugly Muscle' Composed by The Primitive Calculators 'Window to the World' Written by Ollie Olsen, Performed by Whirlywirld 'Happy Birthday' and 'Mr. -

Forbidden Colours

476 3220 GERARD BROPHY forbidden colours TASMANIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Almost every Australian composer born literature, made Sculthorpe (vernacular) and between the end of the First World War and the Meale (international) obvious first generation end of the baby-boomer generation owes even leaders. The upheavals of 1968, and the social their most modest reputation to a half-truth: that revolution that followed in their wake, helped it was only in the early 1960s that our post- convince their students that their Australian colonial music culture caught up with the world identity should derive from looking both inward and produced its first distinctive national school and outward. But to Brophy in the next Gerard Brophy b. 1953 of composers. In press columns, and in his generation, the first to grow up in a multicultural 1967 book Australia’s Music: Themes of a New globalising environment, such a self-conscious 1 The Republic of Dreams 8’32 Society, Roger Covell gave culturally literate pursuit of Australianness came to seem not only Genevieve Lang harp, Philip South darabukka Australians their first reliable list of composers creatively irrelevant, but a failure of imagination. worth following, most of them contemporary. For Brophy, what would once have been Mantras [14’36] And what Donald Peart dubbed ‘The Australian described as a ‘cosmopolitan’ outlook comes 2 Mantra I 3’42 Avant-garde’ owed as much to frustrations of naturally to a contemporary Australian artist. 3 Mantra II 3’10 journalists, academics and conductors with the 4 Mantra III 7’44 deadening local cult of ‘musical cobwebs’ as it Born into an ‘ordinary Anglo-Irish family’ in did to the talents of the new movement’s Sydney’s eastern suburbs, Brophy grew up in 5 Maracatú 11’11 anointed leaders, Peter Sculthorpe, Richard country Coonamble. -

Douglas Lawrence

music for organ, brass, voices, didjeridu and electronics DOUGLAS LAWRENCE REVERBERATIONS ONE REVERBERATIONS TWO Douglas Lawrence, organ Douglas Lawrence, organ music for organ, brass, music for organ, didjeridu, and electronic tape voices, and electronics 1 Cathedral Music I * 1 Sanctus * Ian Bonighton 13’05” Ron Nagorcka 20’25” 2 Toccata 2 Hymn for the death of Felix Werder 10’35” Jesus James Penberthy 6’25” 3 Theme and Variations 3 Scherzo (‘Devils up there’) Ron Nagorcka 11’00” James Penberthy 4’15” 4 Paraphrase ‘In Five’ + 4 Holy Thursday Mass = Statico 2 Felix Werder 4’50” Keith Humble 10’50” * didjeridu / Ralph Nicholls * The Festival Brass electronics / Tim Robinson Ensemble voices / Ernie Althoff, Andrew trumpets / Boris Belousov, Bernard, Ann Blare, Mars John Grey, Robert Harry McMillan, Ron Nagorcka, trombones / Robert Clark, Susan Nagorcka, Jane Eric Klay O’Brien, Tim Tyler, Andrew Uren Cover design / Peter Green Registration assistance by Photography (front) / Ann Blore and Rod Junor. The Ivan Gaal production of Reverberations Engineering / two has been assisted by the Martin Wright Australia Council Production / Photograph of Douglas Nicholas Alexander Lawrence (back) / Paul Wright Artwork (inside back) / Peter Green P 1973/1979/2000 MOVE RECORDS move.com.au essence of the toccata mentality. Structured worked as an assistant. In 1960 he founded and Reverberations lines that burst out of the frame; shadowy free directed the Centre de Musique at the American movement and accoustical happenings that bear Artists Centre in Paris. Six years later he returned one witness to the influence of electronics and textures to the Faculty of Music in Melbourne University that are mirrored so that the work ends in exact becoming in charge of the then new Electronic IAN BONIGHTON (1942-1975) was rapidly gaining inverse of its opening.” Music Studio. -

When Director Richard Lowenstein Opened the First Page of the Novel

DOGS IN SPACE SYNOPSIS Set against the backdrop of Melbourne‟s late 70s punk rock scene, Dogs in Space chronicles life in a chaotic, squalid share house. Hippies, addicts, students and radicals fill their days and nights with sex, drugs, parties and television. A series of chaotic vignettes are balanced with the central romance between Sam (Michael Hutchence), the lead singer of the band, Dogs in Space and his lover Anna (Saskia Post) as the house spirals out of control. Hutchence is a brilliant symbol of reckless youth in this, his first dramatic screen role, giving Dogs in Space instant cult status upon its original release in 1986. Shortly following its release, Dogs in Space achieved cult status, and received Official Selection for the Berlin, Edinburgh, London, and New York Film Festivals. It has since been described by Geoff Andrew of Time Out as an "uplifting and deliciously different movie,” and was also singled out for praise by Harlan Kennedy of Film Comment magazine as one of a number of films from the late 1980s which brought “shifting perspectives, structural experiment, and highly discomforting stories and characters” into the fold of Australian cinema. Unscreened for over twenty years, this classic film has been painstakingly restored from the original negative and remixed in 5.1 digital sound. PRODUCTION COMPANIES GHOST PICTURES PTY. LTD. CENTRAL PARK FILMS PTY. LTD. ENTERTAINMENT MEDIA THE BURROWES FILM GROUP FILM VICTORIA AUSTRALIAN DISTRIBUTOR UMBRELLA ENTERTAINMENT COPYRIGHT: 2009 ORIGINAL RELEASE DATE: JANUARY 1, 1987. RATING: MA RUNNING TIME: 103 MINUTES ORIGINAL FILM STOCK: KODAK 5294, COLOUR. ORIGINAL FORMAT: 35MM DISTRIBUTION FORMAT: HDCAM LOCATION: MELBOURNE, VICTORIA, AUSTRALIA. -

Quintet for Eb Alto Saxophone and String Quartet

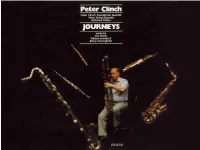

his recording contains work As Eric Gross had written written for me over the past works for me to play in 9 years. Each work was London during 1976 and T later in Europe, I suggested composed for a specific occasion, the idea of the likelihood of a all of them (except “Journeys” work for this particular type by Barry Conyngham) were of ensemble. In his usual written to be part of important enthusiastic manner, Eric overseas engagements. The music took up the challenge, and reflects a close collaboration with certainly succeeded. At first there were a number the composers in an attempt of unsuccessful attempts to produce more worthwhile to perform it in Australia, Australian clarinet and saxophone as few established quartets music. were willing to perform The only disappointing feature anything other than their of these attempts is the lack standard repertoire. So the first performance was of any facility in Australia to given in Germany in 1982 publish the music, such as an with a string quartet from organization like Donemus in Munich. These performances Holland. Because of the many were received with great requests for copies of the music – enthusiasm by the German particularly overseas – numerous audiences. Shortly afterwards the Petra Quartet agreed unsuccessful attempts were made to record it, and they to find publishers both within and approached it with their usual outside Australia. As the result, artistic enthusiasm. The work this recording is a means of certainly demonstrates the keeping the music alive, and the composer’s craftsmanship only published documentation of and it is hoped that more live Quintet for Eb Alto Saxophone performances can be given of a very worthwhile set of musical the work in the near future. -

Don Banks, Australian Composer

Don Banks, Australian Composer: Eleven Sketches Graham Hair Southern Voices ISBN 1–876463–09–0 First published in 2007 by Southern Voices 38 Diamond Street Amaroo, ACT 2914 AUSTRALIA Southern Voices Editorial Board: Professor Graham Hair, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom Ms Robyn Holmes, Curator of Music, National Library of Australia Professor Margaret Kartomi, Monash University Dr Jonathan Powles, Australian National University Dr Martin Wesley-Smith, formerly Senior Lecturer, Sydney Conservatorium of Music Distributed by The Australian Music Centre, trading asSounds Australian PO Box N690 The Rocks Sydney, NSW 2000 AUSTRALIA tel +(612) 9247 - 4677 fax +(612) 9241 - 2873 email [email protected] website www.amcoz.com.au/amc Copyright © Graham Hair, 2007 This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Enquiries to be made to the publisher. Copying for educational purposes Where copies of part or the whole of the book are made under section 53B or 53D of the Act, the law requires that records of such copying be kept. In such cases the copyright owner is entitled to claim payment. ISBN 1–876463–09–0 Printed in Australia by QPrint Pty Ltd, Canberra City, ACT 2600 and in the UK by Garthland Design and Print, Glasgow, G51 2RL Acknowledgements Extracts from the scores by Don Banks are reproduced by permission of Mrs Val Banks and Mrs Karen Sutcliffe.