Improving Social Protection's Response to Child Poverty and Vulnerability in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Tila Karnali Watershed Profile: Status, Challenges and Opportunities for Improved Water Resource Management

Cover photo: A view of the confluence of the Tila Karnali and the Humla Karnali rivers in the Tila- Karnali Watershed, Kalikot. Photo credit: USAID Paani Program II TILA KARNALI WATERSHED PROFILE: STATUS, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVED WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Program Title: USAID Paani Program DAI Project Number: 1002810 Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Nepal IDIQ Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00014 Task Order Number: AID-367-TO-16-00001 Contractor: DAI Global LLC Date of Publication: March 28, 2019 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. III Table of Contents TABLES ....................................................................................................................... VI FIGURES ................................................................................................................... VIII ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................... IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 2 1. TILA KARNALI WATERSHED: NATURE, WEALTH AND POWER ..... 10 2. NATURE........................................................................................................... 11 2.1. TILA KARNALI WATERSHED ............................................................................... -

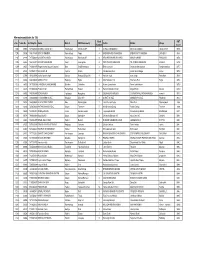

PMT Result 2075 List.Xlsx

Alternate candidates for TSLC Ward PMT S. No. Token No SLC Reg No Name District VDC/Municipality Father Mother Village Number Score 1205 29868 7477022010 BHARAT RAJ BHATT Kanchanpur Bhimdatta NP 8 SHREE NAND BHATT MOTI DEVI BHATT TILACHOUR 997.6 1206 30396 1807718001 BINUTA KHADKA Ramechhap Farpu 4 BADRI BAHADUR KHADKA BISHNU MAYA KHADKA LACHEPU 997.6 1207 32226 7277059022 SUSMITA CHAND Kanchanpur Bhimdatta NP 6 KESHAB BAHADUR CHAND MANJU CHAND BANGAUN 997.6 1208 34943 7441233012 SUSMITA ADHIKARI Kaski Lwangghale 4 TEK PRASAD ADHIKARI TIL KUMARI ADHIKARI KOLELI 997.6 1209 30035 7436031070 Ragani kumari jayswal Jayswal Bara GanjBhawanipur 3 Bhairo parsad Shambha devi jayswal Ganjbhawanipur 997.7 1210 32691 7457005127 SUJATA G M Pyuthan Khaira 2 Nim Bahadur G m Laxmi Gharti Magar Palasi 997.8 1211 32804 7010176010 aasha kumari singh Sunsari RamganjBelgachhi 8 hariram singh nanu singh Ramdhuni 997.8 1212 33666 6946100001 ANDIKA PUN Baglung Righa 6 Man Bahadur Pun Tilachana Pun Righa 997.8 1213 34050 7417059004 CHANDIKA LAMICHHANE Dolakha Chilankha 8 Kumar Lamichhane Rama Lamichhane 997.8 1214 32273 7418082005 Prabin Khatri Ramechhap Deurali 6 Ganesh Bahadur Khatri Maiya Khatri Deurali 997.9 1215 33092 7401013060 SONI MADEN Taplejung Hangdeva 9 SILBAHADUR MADEN SITAMAYA PALUNGWA MADEN eseratol 997.9 1216 33391 7225022009 CHHOISANG GHALE Nuwakot Bidur N.P. 8 SHAKTI GHALE MANMAYA GHALE RAISING 997.9 1217 28738 7436099042 AJAY KUMAR YADAV Bara Madhurijabdi 7 Jhoti Prasad Yadav Mina Devi Madhurijabdi 998 1218 30814 7456070039 PATHA BAHADUR D.C. -

Krishna Bahadur Shahi

CV-Krishna Krishna Bahadur Shahi Born: 29 May 1983 Address: Tilagupha Municipality-6, Kalikot, Nepal Contact No.: Mobile: 9848305151/9858320505 Email: [email protected]/[email protected] Academic Qualifications: 2014 M. A. in Sociology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, Birendranagar Multiple Campus Surkhet (T.U.) 2005 Bachelor in Education, Education Campus Surkhet (T.U.) 2002 Intermediate (+2) in Education, Birendranagar Multiple Campus, Surkhet (HSEB) 2000 S.L.C., Satya Devi H.S. School Jubitha, Kalikot Major Trainings Received: 2nd to 11th Sep. 2006 Professional Report Writing and Proposal Writing by SNV/Nepal 13th to 19th Oct. 2006 Social Mobilization TOT by PAF, Nepal 2008 Start and Improve Your Business SIYB-Level-1 International Labor Organization (ILO)s Two week Training of Trainers' Program by MEDEP, Nepal 21st to 23rd Feb. 2009 Institutional Development (TOT) by PAF, Nepal 25th June to 9th July 2009 Development of Trainers (DOT) by UNICEF/VDRC, Nepal 23rd Aug. to 2nd Sep. 2009 Professional Arc GIS Training by Sea Gate Company, Lalitpur 15th to 22nd Sep. 2009 Tourism Based Micro-Enterprises Development Training by MEDEP, Nepal 11th to 15th Nov. 2009 Transparency, Accountability and Good Governance by SNV/nepal 28th Nov. to 2nd Dec. 2009 Appreciate Inquiry Training by PAF, Nepal 29th Aug. to 2nd Sep. 2013 Value Chain Based GESI (TOT) by HVAP, Surkhet 25th Oct. to 1st Nov. 2013 Cooperative Development, Procurement System and Business Plan Preparation Training by PCU/WUPAP 30th May to 3rd June 2014 Participatory Monitoring, -

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

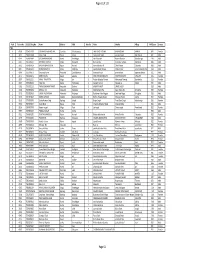

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

Notice Fifth Lot for All PMT Upto 2075.10.13 Selected & Alternate 2Nd Quintile

मत / / गतेको "गोरखाप दैनक "मा काशत सुचना अनुसार ावधक श ालयहमा डलोमा तहमा भनाx भएर वगत (चार पटक ) मा परयोजनाले सुचना काशन गदाx तो"कएको #यादभ$ आवेदन दताx गराउन छु टेका व(याथ*हले छा$वि-तृ आवेदन (Scholarship Application) फाराम परयोजनाको वेवसाइट www.event.gov.np बाट डाउनलोड गर2 भरेर श ालयले मा3णत गर2 प"रयोजना स%चवालय , वु'नगरमा मत /( /() काया* य समयभ दताx गराउनुहोला । सो5ह सुचना अनुसार डलोमा तहमा बाँक8 रहेका 99 कोटामा छा$वि-तमाृ छनोट गन: योजनका लाग पुवx काशन भएको पएमट2 यो;यता<म अनुसारको =>?@ जनाको नामावल2 । नोट : आवेदन फाराम प"रयोजनाका पुवx सुचनाह1 अनुसार दताx ग"रसकेका 2व3याथ5ह1ले भनु x नपन6 । Selected candidates for Diploma Ward Token VDC/Municipa PMT SN. SLC Reg No Name District Numb Father Mother Village No lity Score er 1 34871 7416018187 SRIJANA KUMARI MAHATO Siraha RamnagarMirchaiya 7 BINDESHWAR MAHATO SUDI RAM DULARI DEVI BAN KARYALAYA CHOWK884.5 2 28644 7259004015 DANSINGH ROKAYA Humla ShreeNagar 5 Barkhe Rokaya Gorikala Parki Rokaya Village 899 3 28719 7059004006 BANDANA PHADERA Humla ShreeNagar 4 Netra Phadera Pushi Phadera Phadera Gaun 905 4 32936 7224003027 JEEWAN KUMAR NEUPANE Rasuwa Dhaibung 4 Khem Raj Neupane Chet Kumari Neupane Katunje 907.5 5 32696 7063022017 KAMAL ROKAYA Jumla Lihi(Rara) 6 MAN BAHADUR ROKAYA MANMA ROKAYA LIHI 910 6 32817 7124013003 Ghyu Jyalmo Tamang Rasuwa Gatlang 8 Kawa Tamang Dawa Chamo Tamang Gre 910.5 7 29380 6562005014 Dipak Kumar Shahi Kalikot Jubika 6 Harsa Bahadur Shahi Padma Shahi Jubitha 911.7 8 30311 7372001067 DEEPA PARIYAR Doti Dipayal Silgadhi N.P.5 DILIP PARIYAR NIRMALA PARIYAR SILGADI 915.5 -

How Does Social Protection Contribute to Social Inclusion in Nepal?

February 2014 Report How does social protection contribute to social inclusion in Nepal? Evidence from the Child Grant in the Karnali Region Tej Prasad Adhikari1, Fatik Bahadur Thapa1, Sonam Tamrakar1, Prakash Buda Magar1, Jessica Hagen-Zanker2 and Babken Babajanian2 1NEPAN 2ODI This study uses a social exclusion lens to analyse the effects of Nepal’s Child Grant in Karnali region and tests assumptions about the role social protection can play in contributing to social inclusion and poverty reduction. The study used mixed methods and employed a quasi-experimental impact evaluation. The findings show that in the first three years of implementation, the Child Grant has had only small effects on some indicators of social inclusion, most notably access to a more diversified diet. The research suggests that the impact of the Child Grant is limited by both design and implementation bottlenecks. Shaping policy for development odi.org Preface This report is part of a wider research project that assessed the effectiveness and relevance of social protection and labour programmes in promoting social inclusion in South Asia. The research was undertaken in collaboration with partner organisations in four countries, examining BRAC’s life skills education and livelihoods trainings for young women in Afghanistan, the Chars Livelihoods Programme and the Vulnerable Group Development Programme in Bangladesh, India’s National Health Insurance Programme (RSBY) in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh and the Child Grant in the Karnali region of Nepal. Reports and briefings for each country and a paper providing cross-country analysis and drawing out lessons of relevance for regional and international policy can be found at: www.odi.org/sp-inclusion. -

Karnali Province Tourism Master Plan 2076/77 - 2085/86 BS (2020/21-2029/30)

Karnali Province Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment Surkhet, Nepal Karnali Province Tourism Master Plan 2076/77 - 2085/86 BS (2020/21-2029/30) January 2020 i Karnali Province Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment (MoITFE) Surkhet, Nepal, 2020 KARNALI PROVINCE TOURISM MASTER PLAN 2076/77 - 2085/086 BS (2020/21-2029/30) Technical Assistance WWF Nepal, Kathmandu Office, Nepal Consulting Services Mountain Heritage, Kathmandu, Nepal Advisors Hon. Nanda Singh Budha : Minister; Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment/Karnali Province Dr. Krishna Prasad Acharya : Secretary; Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment/Karnali Province Mr. Dhirendra Pradhan : Ex- Secretary; Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment/Karnali Province Dr. Ghana Shyam Gurung : Country Representative, WWF Nepal Mr. Santosh Mani Nepal : Senior Director, WWF Nepal Focal Persons Ms. Anju Chaudhary : MoITFE/Karnali Province Mr. Eak Raj Sigdel : WWF Nepal Planning Expert Team Members Ms. Lisa Choegyel : Senior Tourism Marketing Advisor Mr. Ram Chandra Sedai : Team Leader/Tourism Expert Dr. Roshan Sherchan : Biodiversity Expert Mr. Jailab K. Rai : Socio-Economist and Gender Specialist Er. Krishna Gautam : Environmental Engineer Mr. Harihar Neupane : Institutional and Governance Expert Mr. Yuba Raj Lama : Culture Expert Cover Photo Credit Ram C.Sedai (All, except mentioned as other's), Bharat Bandhu Thapa (Halji Gomba & Ribo Bumpa Gomba), Chhewang N. Lama (Saipal Base Camp), Dr. Deependra Rokaya (Kailash View Dwar), www.welcometorukum.org (Kham Magar), Google Search (Snow Leopard, Musk Deer, Patal Waterfall, Red Panda). ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Consultant Team would like to acknowledge following institutions and individuals for their meaningful contribution towards the formulation of Karnali Province Tourism Development Master Plan. -

Kalikot-District-Prayer-Guide-Nepali

g]kfn b]zsf] nfuL k|fy{fgf ug{' xf]: x'Dnf d'u' h'Dnf sfnLsf]6 8f]Nkf s0f{fnL, sfnLsf]6 o]z" v|Li6sf] gfpFdf ;a}nfO{ ho dl;x Û xfd|f] ;'Gb/ b]zsf] x/]s ufpFsf] lglDt k|fy{gf ug{ cfk"mnfO{ xfdL ;Fu} ;lDk{t ug'{ ePsf] nfuL wGojfb lbbF5f}+ . o]z" cfk}mn] x/]s ufpFnfO{ k|]d ug'{ x'GYof] eGg] gd'gf cfkmgf] ;]jfsfO{sf] ;dodf cfkmg} r]nfx?nfO{ Pp6f zx/ b]lv csf]{ ufFpx?df hfFbf b]vfpg' eof] . csf]{ s'/f], o]z" cfkm}n] cfkmgf] r]nfx?nfO{ cfk'mn] u/]em}+ ug{ l;sfpg] / ljleGg ufpFdf k7fpg] sfd ug'{ eof] . afbdf, pxfFn] ;Q/L hgfnfO{ klg b'O{–b'O{ hgf u/L ljleGg ufpFdf k7fpg' eof] . n'sf *–!) cWofo . t/, xfdLx?n] cfh s;/L xfd|f] b]z g]kfnsf] #,(*$ uf=lj=;= sf] lglDt k|fy{gf ug]{< gx]Dofxsf] ;dodf, o?zn]dsf] kv{fn elTsPsf] va/ ox'bfsf bfHo–efO{x?n] NofP . o; kf7df kv{fn zAbn] /Iff, ;'/Iff, cflzif clg Pp6f eljiosf] cfzf b]vfpFb5 . gx]Dofxn] k|fy{gf u/], pkjf; a;], clg dflg;x?sf] kfksf] lglDt kZrtfk klg u/] . k/dk|e'n] gx]Dofxsf] k|fy{gfsf] pQ/ lbg'eof] . w]/} 7"nf] lhDd]jf/L ;f/f kv{fn k'g lgdf0f{ ug'{ kg]{ sfd pxfFsf] cflzif / cg'u|xdf ;Defj eof] . x/]sn] w]/} lj/f]w / ;tfj6 ;fdfgf ug'{ k/]tf klg cfkmgf] c3f8Lsf] kv{fnsf] lgdf0f{ ul//x] . o;/Lg}, xfd|f] nflu x/]s ufpF kv{fnsf] Pp6f O§f h:t} xf] . -

KIRDARC Annual Report 2019

REACHING THE UNREACHED Annual Report 2019 Publisher: Karnali Integrated Rural Development and Research Centre (KIRDARC), Nepal P.O. Box: 20842, Sanepa, Lalitpur, Nepal, Tel: +977-1-5548321/5548040 Fax: +977-1-554903 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.kirdarc.org © KIRDARC 2019 Design & Printed at: Masterpiece with Imagination (9851031259) MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR Welcome to KIRDARC annual report undertaken by KIRDARC in 2019 for the 2019. As of 2019, KIRDARC under different strategic areas with has completed its glorious 20 years an aim to reaching the unreached. working in the remote mountain KIRDARC’s work has positively communities in Nepal.During the past affected the relationship between 20 years KIRDARC has contributed people and their government to many development milestones representatives, leading to more including Education , WASH, Health effective delivery of all manner of with Good Governance, Human public services. Rights and Democracy, Gender and Social inclusion , Climate Change On behalf of the Executive Board, I and Disaster. This is the first year of am immensely grateful to our staff our strategic planning period (2019- for their commitment and dedication 2023), and our focus has been on in working together or impacting aligning the organisation with our the lives of the remote communities. revised strategy. To better meet the We look ahead to next year, and to needs of the communities we have continued service to the remote moved towards more integrated communities. We are grateful to local programmes, and this is reflected in government stakeholders, funding this report. partners, local communities for placing their trust in us. I would like to express our gratitude to all our stakeholders and partners, Thank you Government of Nepal, Supporting Partner organisations and others who support our work, who have made this work possible and enabled us to move toward our vision: Just and propserous society . -

RAR of Kalikot

Rapid Assessment Report On Hunger Situation in Kalikot 12 ? 21 July, 2006 1 1 The Lutheran World Federation Nepal Western Region Coordination Unit Nepalgunj, Banke Rapid Assessment Report On Hunger Situation in Kalikot (12 ? 21 July, 2006) Introduction Since 1984, the Lutheran World Federation-Nepal, a humanitarian organization, has been launching programmes related to relief and rehabilitation, and people’s empowerment for sustainable development. Kalikot district that lies in the Karnali Zone reeled under a natural disaster on April 10, 2006. Incessant rain and ferocious hailstorm damaged standing crops and ripe vegetables. Wheat, barley, Uwa, potatoes, fruits and so on were ruined by the rainfall. As food crisis struck the district, villagers sold their properties, jewellery, utensils, and took loans to meet their ends. Various news media gave massive coverage to this incident. Hence, LWF Nepal’s Western Regional Coordination Unit (WRCU) formed a Rapid Assessment Team (RAT) and sent it on July 12, 2006 to conduct research and survey of the district, with the objective of exploring the possibility of providing the victims of food crisis with some relief and assistance. The LWF Nepal, WRCU organized an orientation program to assess the situation and provided guidelines and format for RAT on 12 July, 2006. Objectives · To inspect and survey the areas affected by drought and ha ilstorm in Kalikot. · To acquire a summary understanding of the situation by organizing an interaction programme and establishing coordination with governmental and non-governmental organizations, political parties, civil society and other organizations concerned in Kalikot district. · To conduct a study in and to map the areas in accordance with the standards set earlier.