"Vaudeville Made Him Famous. Hollywood Turned Him Into a Legend. but His Journalism Keeps Him Relevant Generation After Generation."

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Will Rogers and Calvin Coolidge

Summer 1972 VoL. 40 No. 3 The GfJROCEEDINGS of the VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY Beyond Humor: Will Rogers And Calvin Coolidge By H. L. MEREDITH N August, 1923, after Warren G. Harding's death, Calvin Coolidge I became President of the United States. For the next six years Coo lidge headed a nation which enjoyed amazing economic growth and relative peace. His administration progressed in the midst of a decade when material prosperity contributed heavily in changing the nature of the country. Coolidge's presidency was transitional in other respects, resting a bit uncomfortably between the passions of the World War I period and the Great Depression of the I 930's. It seems clear that Coolidge acted as a central figure in much of this transition, but the degree to which he was a causal agent, a catalyst, or simply the victim of forces of change remains a question that has prompted a wide range of historical opinion. Few prominent figures in United States history remain as difficult to understand as Calvin Coolidge. An agrarian bias prevails in :nuch of the historical writing on Coolidge. Unable to see much virtue or integrity in the Republican administrations of the twenties, many historians and friends of the farmers followed interpretations made by William Allen White. These picture Coolidge as essentially an unimaginative enemy of the farmer and a fumbling sphinx. They stem largely from White's two biographical studies; Calvin Coolidge, The Man Who Is President and A Puritan in Babylon, The Story of Calvin Coolidge. 1 Most notably, two historians with the same Midwestern background as White, Gilbert C. -

Grumpy Old Humorist Tells All: Three Short Essays on Writing, Plus Random Thoughts on Same by Ed Mcclanahan

224 Ed McClanahan Grumpy Old Humorist Tells All: Three Short Essays On Writing, Plus Random Thoughts on Same by Ed McClanahan —“I can read readin’, but I can’t read writin’. The reason I can’t read writin’ is, it’s wrote too close to the paper.” —Clem Kadiddlehpopper When book reviewers deign to notice that I exist at all, they tend to refer to me as (among other lower life forms) a “humorist.” I’m always flattered, of course, to be nominated for the post, but I’m afraid I must politely decline to run, on the grounds that it would entail too much responsibility, trying to be funny all the time. The fact is, at my age, being funny ain’t really all that easy—or, to put it another way, being my age ain’t really all that funny . or, for that matter, all that easy either. We’ve all heard it said—usually of some poor, befuddled old bird like me—that “he’s taken leave of his senses.” What actually happens, though, is that our senses often pre- empt us to the punch, and take their own leave almost before we suspect they’re even contemplating a separation, much less a divorce. Corrective measures may, of course, sometimes be taken; cataract surgery is a wonder and a marvel, and I suppose there’s probably one of those “almost invisible” hearing aids circling my head at this very mo- ment, looking for an ear to build its unsightly nest in. My sense of smell has long since abandoned me (an impairment which, having its own occasional compensations, doesn’t even qualify me for disability assistance); and when it left, it took with it a disheartening measure of my sense of taste—so that, at dinnertime, I sit there grieving silently while everyone else is saying grace. -

TERMINAL DRIVE CELL PHONE WAITING AREA OPENS New Location Improves Access to Terminal

Will Rogers World Airport For Immediate Release: June 15, 2020 For More Information Contact: Joshua Ryan, Public Information & Marketing Coordinator Office: (405) 316-3239 Cell: (405) 394-8926 TERMINAL DRIVE CELL PHONE WAITING AREA OPENS New Location Improves Access to Terminal OKLAHOMA CITY, June 15, 2020 – Last week, construction crews put the final touches on a new cell phone waiting area at Will Rogers World Airport. The new area provides 195 parking spaces, improved access to and from Terminal Drive, LED lighting for enhanced visibility, as well as a flow-through design that maximizes parking and means drivers never have to back in or out of a parking space. Signage on southbound Terminal Drive will direct drivers to the new waiting area. The entrance is just south of the Amelia Earhart Lane intersection. The cell phone waiting area is not only a convenient amenity, it helps to improve traffic circulation at the terminal. More cars in the waiting area usually translates to less congestion in the lanes next to the building. And because city ordinance designates the terminal curbside for active loading and unloading only, use of the waiting area also helps drivers avoid a citation. A quick reminder, proper use of a cell phone waiting area means receiving a passenger’s call or text from the curb before approaching the terminal. The passenger should always be ready to load in the vehicle as soon as the driver arrives. The concept of a cell phone waiting area originated after 9/11 when parking curbside at the terminal was no longer permitted. -

“The Grin of the Skull Beneath the Skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 12-2011 “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature Amanda D. Drake University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Drake, Amanda D., "“The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 57. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/57 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature by Amanda D. Drake A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy English Nineteenth-Century Studies Under the Supervision of Professor Stephen Behrendt Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2011 “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” 1 Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature Amanda D. Drake, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Dr. Stephen Behrendt Neither representative of aesthetic flaws or mere comic relief, comic characters within Gothic narratives challenge and redefine the genre in ways that open up, rather than confuse, critical avenues. -

Stand-Up Comedy in Theory, Or, Abjection in America John Limon 6030 Limon / STAND up COMEDY / Sheet 1 of 160

Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America John Limon Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 1 of 160 Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 2 of 160 New Americanists A series edited by Donald E. Pease Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 3 of 160 John Limon Duke University Press Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America Durham and London 2000 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 4 of 160 The chapter ‘‘Analytic of the Ridiculous’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in Raritan: A Quarterly Review 14, no. 3 (winter 1997). The chapter ‘‘Journey to the End of the Night’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in Jx: A Journal in Culture and Criticism 1, no. 1 (autumn 1996). The chapter ‘‘Nectarines’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in the Yale Journal of Criticism 10, no. 1 (spring 1997). © 2000 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ! Typeset in Melior by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 5 of 160 Contents Introduction. Approximations, Apologies, Acknowledgments 1 1. Inrage: A Lenny Bruce Joke and the Topography of Stand-Up 11 2. Nectarines: Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks 28 3. -

215269798.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Comic Vision and Comic Elements of the 18 Century Novel Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe

Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Sayı 25/1,2016, Sayfa 230-238 COMIC VISION AND COMIC ELEMENTS OF THE 18TH CENTURY NOVEL MOLL FLANDERS BY DANIEL DEFOE Gülten SİLİNDİR∗ Abstract “It is hard to think about the art of fiction without thinking about the art of comedy, for the two have always gone together, hand in hand” says Malcolm Bradbury, because the comedy is the mode one cannot avoid in a novel. Bradbury asserts “the birth of the long prose tale was, then the birth of new vision of the human comedy and from that time it seems prose stories and comedy have never been far apart” (Bradbury, 1995: 2). The time when the novel prospers is the time of the development of the comic vision. The comic novelist Iris Murdoch in an interview in 1964 states that “in a play it is possible to limit one’s scope to pure tragedy or pure comedy, but the novel is almost inevitably an inclusive genre and breaks out of such limitations. Can one think of any great novel which is without comedy? I can’t.” According to Murdoch, the novel is the most ideal genre to adapt itself to tragicomedy. Moll Flanders is not a pure tragedy or pure comedy. On the one hand, it conveys a tragic and realistic view of life; on the other hand, tragic situations are recounted in a satirical way. Moll’s struggles to live, her subsequent marriages, her crimes for money are all expressed through parody. The aim of this study is to analyze 18th century social life, the comic scenes and especially the satire in the novel by describing the novel’s techniques of humor. -

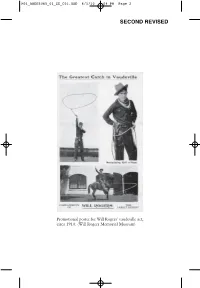

Second Revised

M01_ANDE5065_01_SE_C01.QXD 6/1/10 4:04 PM Page 2 SECOND REVISED Promotional poster for Will Rogers’ vaudeville act, circa 1910. (Will Rogers Memorial Museum) M01_ANDE5065_01_SE_C01.QXD 6/1/10 4:04 PM Page 3 SECOND REVISED CHAPTER 1 Will Rogers, the Opening Act One April morning in 1905, the New York Morning Telegraph’s entertainment section applauded a new vaudeville act that had appeared the previous evening at Madison Square Garden. The performer was Will Rogers, “a full blood Cherokee Indian and Carlisle graduate,” who proved equal to his title of “lariat expert.” Just two days before, Rogers had performed at the White House in front of President Theodore Roosevelt’s children, and theater-goers anticipated his arrival in New York. The “Wild West” remained an enigmatic part of the world to most eastern, urban Americans, and Rogers was from what he called “Injun Territory.” Will’s act met expectations. He whirled his lassoes two at a time, jumping in and out of them, and ended with his famous finale, extending his two looped las- soes to encompass a rider and horse that appeared on stage. While the Morning Telegraph may have stretched the truth— Rogers was neither full-blooded nor a graduate of the famous American Indian school, Carlisle—the paper did sense the impor- tance of this emerging star. The reviewer especially appreciated Rogers’ homespun “plainsmen talk,” which consisted of colorful comments and jokes that he intermixed with each rope trick. Rogers’ dialogue revealed a quaint friendliness and bashful smile that soon won over crowds as did his skill with a rope. -

Will Rogers on Slogans, Syndicated Column, April 1925

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION * HE WENTIES T T WILL ROGERS on SLOGANS Syndicated column, April 12, 1925 Everything nowadays is a Saying or Slogan. You can’t go to bed, you can’t get up, you can’t brush your Teeth without doing it to some Advertising Slogan. We are even born nowadays by a Slogan: “Better Parents have Better Babies.” Our Children are raised by a Slogan: “Feed your Baby Cowlicks Malted Milk and he will be another Dempsey.” Everything is a Slogan and of all the Bunk things in America the Slogan is the Champ. There never was one that lived up to its name. They can’t manufacture a new Article until they have a Slogan to go with it. You can’t form a new Club unless it has a catchy Slogan. The merits of the thing has nothing to do with it. It is, just how good is the Slogan? Jack Dempsey: boxing Even the government is in on it. The Navy has a Slogan: “Join the Navy champion and celebrity of the 1920s and see the World.” You join, and all you see for the first 4 years is a Bucket of Soap Suds and a Mop, and some Brass polish. You spend the first 5 years in Newport News: Virginia city with major naval base Newport News. On the sixth year you are allowed to go on a cruise to Old Point Comfort. So there is a Slogan gone wrong. Old Point Comfort: resort near Newport News Congress even has Slogans: “Why sleep at home when you can sleep in Congress?” “Be a Politicianno training necessary.” “It is easier to fool ’em in Washington that it is at home, So why not be a Senator.” “Come to Washington and vote to raise your own pay.” “Get in the Cabinet; you won’t have to stay long.” “Work for Uncle Sam, it’s just like a Pension.” “Be a Republican and sooner or later you will be a Postmaster.” “Join the Senate and investigate something.” “If you are a Lawyer and have never worked for a Trust we can get you into the Cabinet.” All such Slogans are held up to the youth of this Country. -

Will Rogers' Wit and Wisdom.Pages

Will Rogers’ Wit and Wisdom By Bobbye Maggard Sources: Wikipedia and The Hill “You know horses are smarter than people. You never heard of a horse going broke betting on people.” For those of you who are old enough to remember when political satire evoked laughter instead of lawsuits, here’s an opportunity to revisit a few remarks of “Oklahoma’s Favorite Son,” Will Rogers. And for those of you too young to remember him, here’s your invitation to peek into the life and times of “America’s Favorite Humorist.” Rogers’ witty political observations are just as fresh and appropriate today as they were in the early 20th century. Born on November 4, 1879 on the Dog Iron Ranch in Indian Territory, Rogers was the youngest of eight children of Clement Vann Rogers, and his wife, Mary America Schrimisher. Both parents were part Cherokee. and prominent members of the Cherokee Nation. Rogers often quipped, “ My ancestors did not come over on the Mayflower,..they "met the boat.” Rogers was an avid traveler, and went around the world three times. He made 71 movies—both silent and “talkies,”— wrote more than 4,000 syndicated newspaper columns, and was the leading political wit of the 1930’s. His prowess with a lasso landed him an act in the Ziegfeld Follies, which catapulted him into the movies. At one time Rogers was the highest paid movie star in Hollywood. In the 1920’s his newspaper columns and radio appearances were wildly popular, and provided his audiences with first-hand accounts of his world travels. -

Will Rogers: Native American Cowboy, Philosopher, and Presidential

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Escuela de Lengua y Literatura Inglesa ABSTRACT This senior thesis, “Will Rogers: Native American Cowboy, Philosopher, and Presidential Advisor,” presents the story of Will Rogers, indicating especially the different facets of his life that contributed to his becoming a legend and a tribute to the American culture. Will Rogers is known mostly as one of the greatest American humorist of his time and, in fact, of all times. This work focuses on the specific events and experiences that drove him to break into show business, Hollywood, and the Press. It also focuses on the philosophy of Will Rogers as well as his best known sayings and oft-repeated quotations. His philosophy, his wit, and his mirth made him an important and influential part of everyday life in the society of the United States in his day and for years thereafter. This project is presented in four parts. First, I discuss Rogers’ childhood and his life as a child-cowboy. Second, I detail how he became a show business star and a popular actor. Third, I recall his famous quotations and one-liners that are well known nowadays. Finally, there is a complete description of the honors and tributes that he received, and the places that bear Will Rogers name. Reading, writing, and talking about Will Rogers, the author of the phrase “I never met a man I didn’t like,” is to tell about a life-story of “completeness and self-revelation,” because he was a great spirit, a great writer, and a great human being. CONTENTS TABLE CHAPTER I: Biography of Will Rogers……………………………............ -

Donoso the Humorist: a Study of Entropy

DONOSO THE HUMORIST: A STUDY OF ENTROPY _____________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _____________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY _____________________________________________________ by John A. Cunicelli August 2017 Examining Committee Members: Hortensia Morell, Advisory Chair, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Hiram Aldarondo, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Sergio Ramírez-Franco, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Michael Colvin, External Reader, Marymount Manhattan College ii © Copyright 2017 by John A. Cunicelli All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Donoso the Humorist: A Study of Entropy John A. Cunicelli Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2017 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Hortensia Morell For over two millennia, humor has been the topic of philosophical discussion since it appears to be a nearly universal element of human experience and offers different perspectives on that experience. Humor delves deep into the cultural norms governing religion, family, sex, society, and other aspects of day to day life in order to investigate the absurdities therein. Viewing such reified aspects of life in a new, humorous light is one of the principal characteristics of the Chilean author José Donoso’s novels. Oftentimes irreverent and scathing, Donoso’s dark humor reaches entropic proportions since it accentuates (and at times even seems to celebrate) the human condition’s descent into chaos. Given this downward trajectory, a selection of the Chilean author’s novels will be analyzed under the entropic humor theory originated by literary theorist Patrick O’Neill. The notion of entropy contains the very idea of a breakdown of order that tends toward chaos, so this special brand of humor is a unique fit for a study of Donoso.