Will Rogers and Calvin Coolidge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cosmos Club: a Self-Guided Tour of the Mansion

Founded 1878 The Cosmos Club - A Self-Guided Tour of the Mansion – 2121 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20008 Founders’ Objectives: “The advancement of its members in science, literature, and art,” and also “their mutual improvement by social intercourse.” he Cosmos Club was founded in 1878 in the home of John Wesley Powell, soldier and explorer, ethnologist and T Director of the Geological Survey. Powell’s vision was that the Club would be a center of good fellowship, one that embraced the sciences and the arts, where members could meet socially and exchange ideas, where vitality would grow from the mixture of disciplines, and a library would provide a refuge for thought and learning. www.cosmosclub.org Welcome to The Townsend Mansion This brochure is designed to guide you on a walking tour of the public rooms of the Clubhouse. Whether member or guest, please enjoy the beauty surrounding you and our hospitality. You stand within an historic mansion, replete with fine and decorative arts belonging to the Cosmos Club. The Townsend Mansion is the fifth home of the Cosmos Club. Within the Clubhouse, Presidents, members of Congress, ambassadors, Nobel Laureates, Pulitzer Prize winners, scientists, writers, and other distinguished individuals have expanded their minds, solved world problems, and discovered new ways to make contributions to humankind, just as the founders envisioned in 1878. The history of the Cosmos Club is present in every room, not as homage to the past, but as a celebration of its continuum serving as a reminder of its origins, its genius, and its distinction. ❖❖❖ A place for conscious, animated discussion A place for quiet, contemplation and research A place to free the mind through relaxation, music, art, and conviviality Or exercise the mind and match wits A place of discovery A haven of friendship… The Cosmos Club A Brief History The Townsend Mansion, home of the Cosmos Club since 1952, was originally built in 1873 by Judge Curtis J. -

William Allen White Newspaper Editor ( 1868 - 1944 )

William Allen White Newspaper editor ( 1868 - 1944 ) William Allen White was a renowned newspaper editor, politician, and author. Between the two world wars, White, known as the “Sage of Emporia,” became the iconic middle-American spokesman for millions throughout the United States. Born in Emporia, Kansas, White attended the College of Emporia and the University of Kansas. In 1892 he started work at The Kansas City Star as an editorial writer and a year later married Sallie Lindsay. In 1895, White purchased his hometown newspaper, the Emporia Gazette for $3,000. He burst on to the national scene with an August 16, 1896 editorial entitled “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” White developed a friendship with President THEODORE ROOSEVELT in the1890s that lasted until Roosevelt’s death in 1919. The two would be instrumental in forming the Progressive (Bull-Moose) Party in 1912 in opposition to the forces surrounding incumbent Republican president WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT. Later, White supported much of the New Deal, but opposed FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT in his first three Presidential elec- tions. White died before voting in the 1944 election. Courtesy of Kenneth Neill Despite differences with FDR, White agreed to Roosevelt’s request to help generate public support for the Allies before America’s entrance into World War II. White was fundamental in the formation of the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, sometimes known asthe White Committee. He spent much of his last three years involved with the committee. He won a 1923 Pulitzer Prize for an editorial he wrote after being arrest- ed in a dispute over free speech following objections to the way Kan- sas treated the workers who participated in the railroad strike of 1922. -

A History of Legal Specialization

South Carolina Law Review Volume 45 Issue 5 Conference on the Commercialization Article 17 of the Legal Profession 5-1993 Know the Law: A History of Legal Specialization Michael S. Ariens St. Mary's University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ariens, Michael S. (1993) "Know the Law: A History of Legal Specialization," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 45 : Iss. 5 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol45/iss5/17 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ariens:KNOW Know the THE Law: ALAW: History of A Legal HISTORY Specialization OF LEGAL SPECIALIZATION MICHAEL ARIENS I. INTRODUCTION .............................. 1003 II. THE AUTHORITY OF LAWYERS ..................... 1011 M. A HISTORY OF SPECIALIZATION .................... 1015 A. The Changing of the Bar: 1870-1900 .............. 1015 B. The Business of Lawyers: 1900-1945 .............. 1022 C. The Administrative State and the Practice of Law: 1945-69 1042 D. The End of the Beginning: 1970-Present ............ 1054 IV. CONCLUSION ............................... 1060 I. INTRODUCTION In 1991, Victoria A. Stewart sued her former employer, the law firm of Jackson & Nash, claiming that it negligently misrepresented itself and fraudulently induced her to join the firm. Stewart claimed that she joined Jackson-& Nash after being told that the firm had been hired by a major client for assistance with environmental law issues and that she would manage the firm's environmental law department. -

"In the Pilgrim Way" by Linda Ashley, A

In the Pilgrim Way The First Congregational Church, Marshfield, Massachusetts 1640-2000 Linda Ramsey Ashley Marshfield, Massachusetts 2001 BIBLIO-tec Cataloging in Publication Ashley, Linda Ramsey [1941-] In the pilgrim way: history of the First Congregational Church, Marshfield, MA. Bibliography Includes index. 1. Marshfield, Massachusetts – history – churches. I. Ashley, Linda R. F74. 2001 974.44 Manufactured in the United States. First Edition. © Linda R. Ashley, Marshfield, MA 2001 Printing and binding by Powderhorn Press, Plymouth, MA ii Table of Contents The 1600’s 1 Plimoth Colony 3 Establishment of Green’s Harbor 4 Establishment of First Parish Church 5 Ministry of Richard Blinman 8 Ministry of Edward Bulkley 10 Ministry of Samuel Arnold 14 Ministry of Edward Tompson 20 The 1700’s 27 Ministry of James Gardner 27 Ministry of Samuel Hill 29 Ministry of Joseph Green 31 Ministry of Thomas Brown 34 Ministry of William Shaw 37 The 1800’s 43 Ministry of Martin Parris 43 Ministry of Seneca White 46 Ministry of Ebenezer Alden 54 Ministry of Richard Whidden 61 Ministry of Isaac Prior 63 Ministry of Frederic Manning 64 The 1900’s 67 Ministry of Burton Lucas 67 Ministry of Daniel Gross 68 Ministry of Charles Peck 69 Ministry of Walter Squires 71 Ministry of J. Sherman Gove 72 Ministry of George W. Zartman 73 Ministry of William L. Halladay 74 Ministry of J. Stanley Bellinger 75 Ministry of Edwin C. Field 76 Ministry of George D. Hallowell 77 Ministry of Vaughn Shedd 82 Ministry of William J. Cox 85 Ministry of Robert H. Jackson 87 Other Topics Colonial Churches of New England 92 United Church of Christ 93 Church Buildings or Meetinghouses 96 The Parsonages 114 Organizations 123 Sunday School and Youth 129 Music 134 Current Officers, Board, & Committees 139 Gifts to the Church 141 Memorial Funds 143 iii The Centuries The centuries look down from snowy heights Upon the plains below, While man looks upward toward those beacon lights Of long ago. -

TERMINAL DRIVE CELL PHONE WAITING AREA OPENS New Location Improves Access to Terminal

Will Rogers World Airport For Immediate Release: June 15, 2020 For More Information Contact: Joshua Ryan, Public Information & Marketing Coordinator Office: (405) 316-3239 Cell: (405) 394-8926 TERMINAL DRIVE CELL PHONE WAITING AREA OPENS New Location Improves Access to Terminal OKLAHOMA CITY, June 15, 2020 – Last week, construction crews put the final touches on a new cell phone waiting area at Will Rogers World Airport. The new area provides 195 parking spaces, improved access to and from Terminal Drive, LED lighting for enhanced visibility, as well as a flow-through design that maximizes parking and means drivers never have to back in or out of a parking space. Signage on southbound Terminal Drive will direct drivers to the new waiting area. The entrance is just south of the Amelia Earhart Lane intersection. The cell phone waiting area is not only a convenient amenity, it helps to improve traffic circulation at the terminal. More cars in the waiting area usually translates to less congestion in the lanes next to the building. And because city ordinance designates the terminal curbside for active loading and unloading only, use of the waiting area also helps drivers avoid a citation. A quick reminder, proper use of a cell phone waiting area means receiving a passenger’s call or text from the curb before approaching the terminal. The passenger should always be ready to load in the vehicle as soon as the driver arrives. The concept of a cell phone waiting area originated after 9/11 when parking curbside at the terminal was no longer permitted. -

Kemper Correspondence to 1952 Box 1 Samples of Stationery Used by Mr

Kemper Correspondence to 1952 Box 1 Samples of Stationery Used by Mr. Kemper Abbott Academy July 48-4MH NOV. 51 about 25 lett. Cassures him that j Miss Hearsey welcomes JMK and]fhis Job will not be mpnotnnous. JMK's mother was an Abbot alumnae. An account of esp^y fund-raising problems written by the Rev. John Lord Tjiylor, treas. from 1852-?? Routine stuff. American Acad, of Arts & Sciences 49 2 lett. Routine. Accelerated program A memo prepared for JMK by Richaard Pleter (7) In 1951 explaining PA's program during WWII for boys drafted during a school year. Admission Research CommltteelEnrollment about 50 pages* 19^9 committee studied entrance exams, examined faculty & parent complaints, and analyzed the mortality rate of PA students as a basis for possible changes in admission policies & recruiting. Notes & minutes of meetings. This study is prompted by a lack of high- quality, full-tuition applicants. Lots of charts, statistics, & data. Alumni Educational Policy Committee 51-52 about 40 pages Mostly corres. with members setting up the committee meetings and agendas. Some t* syaow- alumni comment on what the faculy should get. 48-52 Addison Gallery of American Art thick file Lists of Gifts of art to Addison Gallery. Resume of a discussion on art as part of a genjal education. Bart Hayes suggests purchasing some Currier & Ives and other prints decorating the Inn (1949) Report on the operation of the Gallery 194?-48. Report of the Arts Assn of N. E. Prep Schools. Annual Reports for 49-50 and 50-51 Addison Gallery 43-48 thick file Annual report in 1943 with sample scripts of the Gallery's radio program on WLAW. -

See Pages 6-7 for a Spread on Past Heads of School

duelos y quebrantos Veritas Super Omnia Vol. CXXXIV, No. 23 January 6, 2012 Phillips Academy Elliott ’94 Selected as Next Abbot Cluster Dean deans serve six-year terms, a By ALEXANDER JIANG decision was made last year to extend Joel’s term until Jennifer Elliott ’94, In- the end of the 2011-2012 year structor in History and So- because two other cluster cial Science, will succeed deans were also leaving their Elisa Joel, Associate Dean of positions and the adminis- Admission, as the next Dean tration wished to avoid too of Abbot Cluster. She will much turnover. commense her six-year term During her time as clus- in Fall 2012. ter dean, Joel has noticed Paul Murphy, Dean of that “the pride students Students, notified Elliott of feel [about] living in Abbot the decision at the beginning cluster has grown over the of Winter Break. years.” Elliott said, “This is work Joel said that she will that I really enjoy doing. I’m miss working with so many excited to get to know Abbot. students. “To be able to “My colleagues in Ab- come to know 220 students bot have already been really is a great opportunity. I’ve welcoming. It’s going to be come to know kids I other- really fun to know the stu- wise wouldn’t know through dents, and I hope that will coaching soccer or advising” help to ease the transition a she said. little bit,” she continued. Year after year, Joel has Though she was once a consistently led her cluster student at Andover, Elliott in organizing Abbot Cabaret, acknowledged that the role Abbot’s annual talent show of a cluster dean has changed in the winter term. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

215269798.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Don Juan Study Guide

Don Juan Study Guide © 2017 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary Don Juan is a unique approach to the already popular legend of the philandering womanizer immortalized in literary and operatic works. Byron’s Don Juan, the name comically anglicized to rhyme with “new one” and “true one,” is a passive character, in many ways a victim of predatory women, and more of a picaresque hero in his unwitting roguishness. Not only is he not the seductive, ruthless Don Juan of legend, he is also not a Byronic hero. That role falls more to the narrator of the comic epic, the two characters being more clearly distinguished than in Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. In Beppo: A Venetian Story, Byron discovered the appropriateness of ottava rima to his own particular style and literary needs. This Italian stanzaic form had been exploited in the burlesque tales of Luigi Pulci, Francesco Berni, and Giovanni Battista Casti, but it was John Hookham Frere’s (1817-1818) that revealed to Byron the seriocomic potential for this flexible form in the satirical piece he was planning. The colloquial, conversational style of ottava rima worked well with both the narrative line of Byron’s mock epic and the serious digressions in which Byron rails against tyranny, hypocrisy, cant, sexual repression, and literary mercenaries. -

Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995), 143–65

NOTES Introduction 1. On the formidable mythology of the Watergate experience, see Michael Schudson, The Power of News (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995), 143–65. 2. Adam Gropkin, “Read All About It,” New Yorker, 12 December 1994, 84–102. Samuel Kernell, Going Public: New Strategies of Presidential Leader- ship, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 1993), 55–64, 192–6. 3. Michael Baruch Grossman and Martha Joynt Kumar, Portraying the Presi- dent:The White House and the News Media (Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981), 19–28. See also Stephen Hess, The Government- Press Connection (Washington, D.C.: Brookings, 1984). 4. Kenneth T.Walsh, Feeding the Beast:The White House versus the Press (New York:Random House, 1996), 6–7. 5. Thomas E. Patterson,“Legitimate Beef:The Presidency and a Carnivorous Press,” Media Studies Journal 8 (No. 2, Spring 1994): 21–6. 6. See, among others, Robert Entman, Democracy without Citizens: Media and the Decay of American Politics (New York: Oxford, 1989), James Fallows, Breaking the News (New York: Pantheon, 1996), and Thomas E. Patterson, Out of Order (New York:Vintage, 1994). 7. Larry J. Sabato, Feeding Frenzy: How Attack Journalism Has Transformed Poli- tics (New York: Free Press, 1991) is credited with popularizing use of the phrase. 8. See, generally, John Anthony Maltese, Spin Control:The White House Office of Communications and the Management of Presidential News, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994). 9. Jennifer Waber,“Secrecy and Control: Reporters Committee says Clinton Administration’s dealings with the press have become more antagonistic,” Editor and Publisher, 24 May 1997, 10–13, 33–4. -

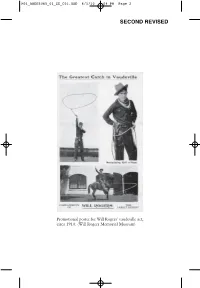

Second Revised

M01_ANDE5065_01_SE_C01.QXD 6/1/10 4:04 PM Page 2 SECOND REVISED Promotional poster for Will Rogers’ vaudeville act, circa 1910. (Will Rogers Memorial Museum) M01_ANDE5065_01_SE_C01.QXD 6/1/10 4:04 PM Page 3 SECOND REVISED CHAPTER 1 Will Rogers, the Opening Act One April morning in 1905, the New York Morning Telegraph’s entertainment section applauded a new vaudeville act that had appeared the previous evening at Madison Square Garden. The performer was Will Rogers, “a full blood Cherokee Indian and Carlisle graduate,” who proved equal to his title of “lariat expert.” Just two days before, Rogers had performed at the White House in front of President Theodore Roosevelt’s children, and theater-goers anticipated his arrival in New York. The “Wild West” remained an enigmatic part of the world to most eastern, urban Americans, and Rogers was from what he called “Injun Territory.” Will’s act met expectations. He whirled his lassoes two at a time, jumping in and out of them, and ended with his famous finale, extending his two looped las- soes to encompass a rider and horse that appeared on stage. While the Morning Telegraph may have stretched the truth— Rogers was neither full-blooded nor a graduate of the famous American Indian school, Carlisle—the paper did sense the impor- tance of this emerging star. The reviewer especially appreciated Rogers’ homespun “plainsmen talk,” which consisted of colorful comments and jokes that he intermixed with each rope trick. Rogers’ dialogue revealed a quaint friendliness and bashful smile that soon won over crowds as did his skill with a rope.