Low Budget Audio-Visual Aesthetics in Indie Music Video and Feature Filmmaking: the Works of Steve Hanft and Danny Perez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1

Teaching Classical Languages Volume 10, Issue 2 Kopestonsky 71 Never Out of Style: Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1 Theodora B. Kopestonsky University of Tennessee, Knoxville ABSTRACT Students often struggle to interpret Latin poetry. To combat the confusion, teachers can turn to a modern parallel (pop music) to assist their students in understanding ancient verse. Pop music is very familiar to most students, and they already trans- late its meaning unconsciously. Building upon what students already know, teach- ers can reframe their approach to poetry in a way that is more effective. This essay shows how to present the concept of meter (dactylic hexameter and elegy) and scansion using contemporary pop music, considers the notion of the constructed persona utilizing a modern musician, Taylor Swift, and then addresses the pattern of the love affair in Latin poetry and Taylor Swift’s music. To illustrate this ap- proach to connecting ancient poetry with modern music, the lyrics and music video from one song, Taylor Swift’s Blank Space (2014), are analyzed and compared to poems by Catullus. Finally, this essay offers instructions on how to create an as- signment employing pop music as a tool to teach poetry — a comparative analysis between a modern song and Latin poetry in the original or in translation. KEY WORDS Latin poetry, pedagogy, popular music, music videos, song lyrics, Taylor Swift INTRODUCTION When I assign Roman poetry to my classes at a large research university, I re- ceive a decidedly unenthusiastic response. For many students, their experience with poetry of any sort, let alone ancient Latin verse, has been fraught with frustration, apprehension, and confusion. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music's

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 #Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture Gabriella Saporito [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Musicology Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Saporito, Gabriella, "#Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8074. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8074 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture Gabriella Saporito Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D., Chair Jennifer Walker, Ph.D. Matthew Heap, Ph.D. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

RESUME FINAL 10-7-19.Xlsx

MacGowan Spencer AWARD WINNING MAKEUP + HAIR DESIGNER, GROOMER I MAKEUP DEPT HEAD I SKIN CARE SPECIALIST + BEAUTY EDITOR NATALIE MACGOWAN SPENCER [email protected] www.macgowanspencer.com Member IATSE Local 706 MakeupDepartment Head FEATURE FILMS Director ▪ Hunger Games "Catching Fire" Francis Lawrence Image consultant ▪ “Bad Boys 2” Michael Bay Personal makeup artist to Gabrielle Union ▪ Girl in a Spiders Web Fede Alvarez Makeup character designer for Claire Foy Trilogy leading lady TV SHOWS/ SERIES ▪ HBO Insecure Season 1, 2 + 3 Makeup DEPT HEAD ▪ NETFLIX Dear White People Season 2 Makeup DEPT HEAD ▪ FOX Leathal Weapon Season 3 Makeup DEPT HEAD ▪ ABC Grown-ish Season 3, episode 306, 307, 308, 309 Makeup DEPT HEAD SHORT FILMS Director SHORT FILMS Director ▪ Beastie Boys "Make Some Noise" Adam Yauch ▪ Toshiba DJ Caruso ▪ Snow White Rupert Sanders ▪ "You and Me" Spike Jonze SOCIAL ADVERTISING: FaceBook, Google, Apple COMMERCIALS Director COMMERCIALS Director ▪ Activia Liz Friedlander ▪ Glidden Filip Engstrom ▪ Acura Martin De Thurah ▪ Heineken Rupert Saunders ▪ Acura W M Green ▪ Honda Filip Engstrom ▪ Adobe Rhys Thomas ▪ Hyundai Max Malkin ▪ Allstate Antoine Fuqua ▪ Infinity Carl Eric Rinsch ▪ Apple "Family Ties" Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu ▪ International Delight Renny Maslow ▪ Applebee's Renny Maslow ▪ Pepperidge Renny Maslow ▪ Applebee's Renny Maslow ▪ Hennessey ▪ AT&T Oskar ▪ Jordan Rupert Sanders ▪ AT&T Rupert Saunders ▪ Kia Carl Eric Rinsch ▪ AT&T Filip Engstram ▪ Liberty Mutual Chris Smith ▪ Catching Fire Francis Lawrence ▪ Lincoln Melinda M. ▪ Chevy Filip Engstram ▪ Miller Lite Antoine Fuqua ▪ Cisco Chris Smith ▪ NFL Chris Smith ▪ Comcast Pat Sherman ▪ Nike Rupert Saunders ▪ Cottonelle Renny Maslow ▪ Nissan Dominick Ferro ▪ Crown Royal Frederick Bond ▪ Pistacios Chris smith ▪ Dannon Liz Friedlander ▪ Pistachios Job Chris smith ▪ Disney Renny Maslow Featuring Snoop Dog, Dennis Rodman + Snooki ▪ Dr. -

Total Barre: Music Suggestions

Music Suggestions for Total Barre® — Modified for Pre- & Post-Natal Music Theme: Popular Music 1. Warm Up 1: Spinal Mobility — 7. Workout 5: Cardio Legs Flexion, Extension, Rotation & Side Bending Music: Pay No Mind (feat. Passion Pit) Music: Go it Alone Length: 4:10 – approx. 120 bpm Length: 4:09 – approx. 84 bpm Artist: Madeon Artist: Beck Album: Adventure (Deluxe) Album: Guero Download: itunes.com Download: itunes.com 8. Workout 6: Standing Abs 2. Warm Up 2: Lower Body — Hip, Knee, Ankle & Foot Music: Burn So Deep (feat. April) Music: Hide Away Length: 5:30 – approx. 108 bpm Length: 4:12 – approx. 132 bpm Artist: Kings of Tomorrow Artist: Kiesza Album: Burn So Deep (Single) Album: Sound of a Woman Download: itunes.com Download: itunes.com 9. Workout 7: Calf, Quad & Adductor 3. Workout 1: Lower Body — Hip, Knee, Ankle & Foot Music: What Do You Mean Music: Heavy Cloud No Rain Length: 3:25 – approx. 130 bpm Length: 3:45 – approx. 115 bpm Artist: Justin Bieber Artist: Sting Album: Purpose (Deluxe) Album: Ten Summoner’s Tales Download: itunes.com Download: itunes.com 10. Floor Work 1: Abs, Back & Arms 4. Workout 2: Upper Body — Arms Front Music: She’s a Super Lady Music: I Found You Length: 5:06 – approx. 126 bpm Length: 3:59 – approx. 138 bpm Artist: Luther Vandross Artist: The Wanted Album: Never Too Much Album: I Found You (Single) Download: itunes.com Download: itunes.com 11. Floor Work 2: Cool Down & Stretching 5. Workout 3: Upper Body — Arms Back Music: Hold You in My Arms Music: Miami 82 (CHI2014 Edit) [Kygo Remix] Length: 5:12 – approx. -

Look Alikes Gadfly Mail Ox in Defense of J.T\.Mericau

THE FLY The St. John's College Student Week{y Annapolis, Maryland Volume XXIV, Issue 5 October 1, 2002 Look Alikes Gadfly Mail ox In Defense of J.t\.mericau. In a quite sophomoric letter to the editor, slaves. But he fails to mention that in the origi Editor-in-Chief Response to the Best Government Money Can Buy: . .lVIr. Nick Colten, of tl1e class of 2005, asked My saying tllat the inlmigrants who come nal draft of the docU111ent, Jefferson harshly Cooper N. Gallimore In hi . 1 'Th Best Government Money the state coffers in any way, the re_sult is es sen me to clarify some alleged contradictions in a to this country do so because t11ey seek refuge s art1c e, e . th b · s ent 1n these pro condemned King George III for promoting Can Buy,' l\1ichael Bridge supported a position ually that" e money ,,emg P column that I published two weeks ago. Being slave trade: from places ruled by mobs also seemed to con Production Managers f: ul tion and mislead- grams ts ta,"X money. a freshman, and following Mr. Cohen's ex fuse Mr. Colten, so I'll try to briefly clear that Ervin Romero . that rests on a a ty assump tl in Indeed if this money zj ta,"X money, it opens "He has waged cruel war against hU111an . ing information. He cons1sten y _assumes ' . Wh should some- ample, I may be expected to respond by writ up. By "mobs" I mean groups of privileged Cathy Keene nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of . -

JEFF CRONENWETH, ASC Director of Photography

JEFF CRONENWETH, ASC Director of Photography o f f i c i a l w e bs i te FEATURES/ TV (partial list) BEING THE RICARDOS Amazon Studios Dir: Aaron Sorkin Prod: Desi Arnaz, Jr., Stuart M. Besser *TALES FROM THE LOOP (Pilot) Amazon Studios Dir: Mark Romanek Trailer Prod: Matt Reeves, Nathaniel Halpern A MILLION LITTLE PIECES Warner Bros. Dir: Sam Taylor-Johnson Trailer Prod: John Wells GONE GIRL 20th Century Fox Dir: David Fincher Trailer Prod: Reese Witherspoon, Ceán Chaffin HITCHCOCK Fox Searchlight, Dir: Sacha Gervasi Trailer Montecito Picture Co. Prod: Tom Pollock, Ivan Reitman **THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO Sony Pictures Dir: David Fincher Trailer Prod: Scott Rudin, Ceán Chaffin ***THE SOCIAL NETWORK Columbia Pictures Dir: David Fincher Trailer Prod: Scott Rudin, Michael De Luca ONE HOUR PHOTO Fox Searchlight Dir: Mark Romanek Trailer Prod: Christine Vachon, Pam Koffler DOWN WITH LOVE 20th Century Fox Dir: Peyton Reed Trailer Prod: Dan Jinks, Bruce Cohen K-19 Paramount, Dir: Kathryn Bigelow Trailer Intermedia Prod: Kathryn Bigelow, Christine Whitaker FIGHT CLUB 20th Century Fox Dir: David Fincher Trailer Prod: Art Linson, Cean Chaffin *2020 Emmy Award Nominee – Outstanding Cinematography for a Single-Camera Series (One Hour) **2011 Academy Awards Nominee – Best Cinematography **2011 American Society of Cinematographers Awards Nominee – Best Cinematography ***2010 Academy Awards Nominee – Best Cinematography ***2010 American Society of Cinematographers Awards Nominee – Best Cinematography, Feature Film COMMERCIALS (partial list) EA -

Continued on Page 8, Column 1 Intelligence, Integrity, and Lead

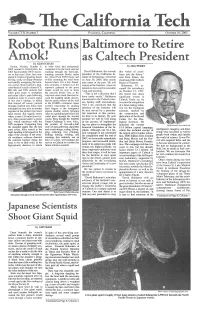

VOLUME NUMBER 3 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA OCTOBER 2005 By ADAM CRAIG Nevada, October 8, to what Alice had erroneously By PERRY 2005, around 11 :30AM Alice, the computed to be the track sent her 2005 Sportsmobile 4WD succes crashing through the barricade, David Baltimore, the seventh this VISIon of excel sor to last year's Bob, had com crushing concrete blocks under president of the California In lence into the future," pleted 8.3 miles ofgrueling desert her robust Ford E350 frame and stitute ofTechnology, will retire said Kent Kresa, the driving, easily avoiding obstacles swiftly mounting the sand berm on June 30, 2006, after nearly chairman ofthe Caltech and handily navigating the tortu beyond them. For a few breath nine years in the post. He will Board ofTrustees. ous course. Team Caltech's dedi less moments, it looked as if the remain at the Institute, where he Baltimore, 67, as cated band ofscruffy-chinned CS, reporters gathered in the press intends to focus on his scientific sumed the presidency and CDS students had stands would be next to share work and teaching. on October 15, 1997. taken great to strengthen the concrete blocks' as the "This is not a decision that I His tenure saw many and refine path-following wayward robot truck barreled to have made easily," Baltimore ward the huddled media masses. significant events at module in order to avoid a repeat announced to the Caltech trust of last year's mishap, in which But the quick reflexes of the staff Caltech. Early on, he Bob strayed off course, plowed at the DARPA command center ees, faculty, staff, and students, oversawthecompletion through a barbed wire fence, then averted catastrophe by guiding "but I am convinced that the of a fund-raising initia entangled his rear axle in another their fingers to the emergency interests of the Institute will tive for the biological segment of the barbed wire fence remote disable switch, bringing be best served by a presiden sciences, marked by upon reentry. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

The German Classics of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Vol. VI. by Editor-In-Chief: Kuno Francke

The German Classics of The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Vol. VI. by Editor-in-Chief: Kuno Francke The German Classics of The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Vol. VI. by Editor-in-Chief: Kuno Francke Produced by Stan Goodman, Jayam Subramanian and PG Distributed Proofreaders VOLUME VI HEINRICH HEINE FRANZ GRILLPARZER LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN THE GERMAN CLASSICS Masterpieces of German Literature TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH page 1 / 754 Patrons' Edition IN TWENTY VOLUMES ILLUSTRATED 1914 CONTRIBUTORS AND TRANSLATORS VOLUME VI CONTENTS OF VOLUME VI HEINRICH HEINE The Life of Heinrich Heine. By William Guild Howard Poems Dedication. Translated by Sir Theodore Martin page 2 / 754 Songs. Translators: Sir Theodore Martin, Charles Wharton Stork, T. Brooksbank A Lyrical Intermezzo. Translators: T. Brooksbank, Sir Theodore Martin, J.E. Wallis, Richard Garnett, Alma Strettell, Franklin Johnson, Charles G. Leland, Charles Wharton Stork Sonnets. Translators: T. Brooksbank, Edgar Alfred Bowring Poor Peter. Translated by Alma Strettell The Two Grenadiers. Translated by W.H. Furness Belshazzar. Translated by John Todhunter The Pilgrimage to Kevlaar. Translated by Sir Theodore Martin The Return Home. Translators: Sir Theodore Martin. Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker, James Thomson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning Twilight. Translated by Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker page 3 / 754 Hail to the Sea. Translated by Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker In the Harbor. Translated by Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker A New Spring. Translators: Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker, Charles Wharton Stork Abroad. Translated by Margaret Armour The Sphinx. Translated by Sir Theodore Martin Germany. Translated by Margaret Armour Enfant Perdu. Translated by Lord Houghton The Battlefield of Hastings. Translated by Margaret Armour The Asra. Translated by Margaret Armour The Passion Flower.