Coyer, Megan Joann (2010) the Ettrick Shepherd and the Modern Pythagorean: Science and Imagination in Romantic Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW ZEALAND GAZR'l*IE

No. 108 2483 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZR'l*IE Published by Authority WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 31 OCTOBER 1974 Land Taken for the Auckland-Hamilton Motorway in the SCHEDULE City of Auckland NORTH AUCKlAND LAND DISTRICT ALL that piece of land containing 1 acre 3 roods 18.7 DENIS BLUNDELL, Governor-General perches situated in Block XIII, Whakarara Survey District, A PROCLAMATION and being part Matauri lHlB Block; as shown on plan PURSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928, I, Sir Edward M.O.W. 28101 (S.O. 47404) deposited in the office of the Denis Blundell, the Governor-General of New Zealand, hereby Minister of Works and Development at Wellington and proclaim and declare that the land first described in the thereon coloured blue. Schedule hereto and the undivided half share in the land Given under the hand of His Excellency the Governor secondly therein described, held by Melvis Avery, of Auck General and issued under the Seal of New Zealand, land, machinery inspector, are hereby taken for the Auckland this 23rd day of October 1974. Hamilton Motorway. [Ls.] HUGH WATT, Minister of Works and Development. SCHEDULE Goo SAVE THE QUEEN! NORTH AUCKLAND LAND DISTRICT (P.W. 33/831; Ak. D.O. 50/15/14/0/47404) ALL those pieces of land situated in the City of Auckland described as follows: A. R. P. Being Land Taken for Road and for the Use, Convenience, or 0 0 11.48 Lot 1, D.P. 12014. Enjoyment of a Road in Blocks Ill and VII, Te Mata 0 0 0.66 Lot 2, D.P. -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Digging up the Kirkyard: Death, Readership and Nation in the Writings of the Blackwood’s Group 1817-1839. Sarah Sharp PhD in English Literature The University of Edinburgh 2015 2 I certify that this thesis has been composed by me, that the work is entirely my own, and that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Sarah Sharp 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Penny Fielding for her continued support and encouragement throughout this project. I am also grateful for the advice of my secondary supervisor Bob Irvine. I would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Wolfson Foundation for this project. Special thanks are due to my parents, Andrew and Kirsty Sharp, and to my primary sanity–checkers Mohamad Jahanfar and Phoebe Linton. -

Burns Chronicle 1892

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1892 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Balerno Burns Club, In Memory of the Founders of Balerno Burns Club - "Let it Blaw" The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com Sam.e_aa Same as ; supplied to aupplied H.R.J1. TH to ,rinee ef ROYALTY Wales, in AND l!OTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMERT. E -)(- FINEST WHISKY Bismllrek, ltt THE WORLD. SOLE PEOPEl.I:lllTO:e., :O,O:&El:.:1,T .15n>Ort 'Uqlbfsllv Metcbant, ff7 Holm Street., & 17 Hope Street, G ~[ '!;.·- .. ~\ • .. , ft '·• t ,' ' ADVBRTISEHENTS,: -' "' ;:Ei.A.'l'EB.SO~, SONS & 00., .,-J ·~ ..... • .. · . GLAS<j-OW. It .. LIST. OF PART .SONGS_ To the A ~· "Burns Clubs" Ott Scotland. I'< :, THE "SCOTTISH MINSTREL. '1 A Stlection of Favourite Bonus, &.c., Harmonised atfd Arranged for Male Yoi~~: 11."dited bg ALEXANDJJ,'R PATTERSON. No. ii' 1. There was a lad was born in Kyle ............. Solo and Chorus ................ T.T.B. 2d. 2. Of a' the airts the wind can blaw .............................................. T.T.B,B. Sd. 8. Afton Water .................................................................. T.T.B.B. Sil. 4. A man's a man fora' tb&t................ Solo and Chorus .................... T.T.B.B. 2d. 6. The deil cam flddlin' thro' the toun ..............................................T.T.B. 3d. 6. Com Rigs ............................ Solo and Chorus ........................ f. T.B.B. 3d• .z.- Bums' Grace .................................................................. T.T.&.B. Sd. '8. 0 Willie brew'd a peek o' mant (Shore) . -

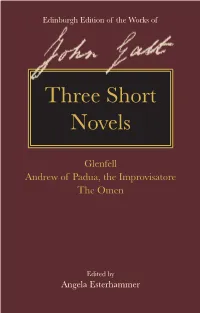

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters. -

Discord & Consensus

c Discor Global Dutch: Studies in Low Countries Culture and History onsensus Series Editor: ulrich tiedau DiscorD & Discord and Consensus in the Low Countries, 1700–2000 explores the themes D & of discord and consensus in the Low Countries in the last three centuries. consensus All countries, regions and institutions are ultimately built on a degree of consensus, on a collective commitment to a concept, belief or value system, 1700–2000 TH IN IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1700–2000 which is continuously rephrased and reinvented through a narrative of cohesion, and challenged by expressions of discontent and discord. The E history of the Low Countries is characterised by both a striving for consensus L and eruptions of discord, both internally and from external challenges. This OW volume studies the dynamics of this tension through various genres. Based C th on selected papers from the 10 Biennial Conference of the Association OUNTRI for Low Countries Studies at UCL, this interdisciplinary work traces the themes of discord and consensus along broad cultural, linguistic, political and historical lines. This is an expansive collection written by experts from E a range of disciplines including early-modern and contemporary history, art S, history, film, literature and translation from the Low Countries. U G EDIT E JANE FENOULHET LRICH is Professor of Dutch Studies at UCL. Her research RDI QUIST AND QUIST RDI E interests include women’s writing, literary history and disciplinary history. BY D JAN T I GERDI QUIST E is Lecturer in Dutch and Head of Department at UCL’s E DAU F Department of Dutch. -

Ku Leuven Faculteit Letteren Masteropleiding Taal- En Letterkunde

KU LEUVEN FACULTEIT LETTEREN MASTEROPLEIDING TAAL- EN LETTERKUNDE The Black Legend and Romantic Orientalism in Moke’s Le Gueux de Mer and Grattan’s The Heiress of Bruges: a comparison Promotor Masterproef Prof. dr. R. Ingelbien ingediend door KIRSTEN VAN PRAET Leuven 2013 ii KU LEUVEN FACULTEIT LETTEREN MASTEROPLEIDING TAAL- EN LETTERKUNDE The Black Legend and Romantic Orientalism in Moke’s Le Gueux de Mer and Grattan’s The Heiress of Bruges: a comparison Promotor Masterproef Prof. dr. R. Ingelbien ingediend door KIRSTEN VAN PRAET Leuven 2013 iii Acknowledgement I would like to express my gratitude to my promoter, professor Ingelbien, for his guidance and the time he spent to ameliorate this thesis. iv Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................ 1 2 The representation of national stereotypes ........................ 5 2.1 The history of national characterization ..................... 5 2.2 The mechanisms of national stereotypes .................... 8 2.3 A definition and three parameters for stereotyping .. 13 3 Romantic Orientalism ...................................................... 17 3.1 Introduction .............................................................. 17 3.2 Characteristics .......................................................... 21 4 The Black Legend ............................................................ 26 4.1 Introduction .............................................................. 26 4.2 The ingredients of the Black Legend ....................... -

No 1, 11 January 1973, 1

No. 1 1 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE Published by Authority WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 11 JANUARY 1973 CoRRIGENDUM Land Taken for a Service Lane in the Bo'rough of Kaikohe IN the notice published in the Gazette, 19 December 1972, DENIS BLUNDELL, Governor-General No. 103, p. 2845 of the Notice of the Intention to Vary A PROCLAMATION Hours for the Sale of Liquor at Licensed Premises Carpenters Arms, for the words "Greys Avenue, Hastings" PURSUANT to the Public Wor,ks Act 1928, I, Sir Edward Denis read "Greys Avenue, Auckland", which last-mentioned words Blundell, the Governor-General of New Zealand, hereby appear in the original notice signed by the Chairman of the proclaim and declare that the land described in the Schedule Auckland District Licensing Committee. hereto is hereby taken for a service lane and shall vest in the Mayor, Councillors, and Citizens of the Borough of Dated at Wellington this 5th day of January 1973. Kaikohe as from the date hereinafter-mentioned; and I also E. A. MISSEN, Secretary for Justice. declare that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after (J. 18/25/237 (5») the 15th day of January 1973. SCHEDULE SoUTH AUCKLAND LAND DISlRICf ALL those pieces of land situated in the Borough of Kaikohe, Land Taken for Road in Block IX, Tairua Survey D'istrict, North Auckland R.D., described as follows: Thames County A. R. P. Being o 0 8.8 Part Kohewhata 44B3 Block; coloured yellow on plan. DENIS BLUNDELL, Governor-General o 0 3.5 Part Kohewhata 44B3 Block; coloured blue on A PROCLAMATION plan. -

New Zealand Gazette Extraordinary

No. 82 1943 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY Published by Authority WELLINGTON, MONDAY, 12 DECEMBER 1960 Resignation of M embers of the Executive Council and of The Honourable Mabel Bowden Howard, holding a seat Ministers in the Executive Council and the office of Minister of Social Security; The Honourable John Mathison, holding a seat in the Executive Council and the offices of Minister of Trans His Excellency the Governor-General has been pleased to port and Minister of Island Territories; accept the resignation of : The Honourable Raymond Boord, holding a seat in the The Right Honourable Walter Nash, C.H., holding a seat in Executive Council and the office of Minister of Customs; the Executive Council and the offi ce of Prime Minister, and Minister of External Affairs, and Minister of Maori The Honourable William Theophilus Anderton, holding Affairs; a seat in the Executive Council and the office of Minister The Honourable Clarence Farringdon Skinner, M.C., hold of Internal Affairs. ing a seat in the Executive Council and the offices of Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Lands; Dated at Wellington this 12th day of December 1960. The Honourable Arnold Henry N ordmeyer, holding a seat By Command- in the Executive Council and the office of Minister of D. C. WILLIAMS, Official Secretary. Finance; The Honourable Henry Greathead Rex Mason, Q.C., hold ing a seat in the Executive Council and the offices of Members of the Executive Council Appointed Attorney-General, Minister of Justice, and Minister of Health; The Honourable Frederick -

Roger Walker

Roger Walker New Zealand Institute of Architects Gold Medal 2016 Roger Walker New Zealand Institute of Architects Gold Medal 2016 B Published by the New Zealand Contents Institute of Architects 2017 Introduction 2 Editor: John Walsh Gold Medal Citation 4 In Conversation: Roger Walker with John Walsh 6 Contributors: Andrew Barrie, Terry Boon, Pip Cheshire, Comments Patrick Clifford, Tommy Honey, Gordon Andrew Barrie Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom 40 Moller and Gus Watt. Tommy Honey Who Dares Wins 42 Gordon Moller Fun, Roger-style 46 All plans and sketches © Roger Walker. Patrick Clifford Critical Architecture 50 Portrait of Roger Walker on page 3 by Gus Watt Reggie Perrin on Willis Street 52 Simon Wilson. Cartoon on page 62 Terry Boon A Radical Response 54 by Malcolm Walker. Pip Cheshire Ground Control to Roger Walker 58 Design: www.inhouse.nz Cartoon by Malcolm Walker 62 Printer: Everbest Printing Co. China © New Zealand Institute of Architects 2017 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-0-473-38089-2 1 The Gold Medal is the highest honour awarded by the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA). It is given to an architect who, over the course of a career (thus far!), has designed a substantial body of outstanding work that is recognised as such by the architect’s peers. Gold Medals Introduction for career achievement have been awarded since 1999 and, collectively, the recipients constitute a group of the finest architects to have practised in New Zealand over the past half century. -

ASSOCIATION for SCOTTISH LITERARY STUDIES Publications

ASSOCIATION FOR SCOTTISH LITERARY STUDIES Publications Gifford, D. ed., The Three Perils of Man. War, Women and Witchcraft, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 1 (1972) Turnbull, A. ed., The Poems of John Davidson. Vol. I, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 2 (1973) Turnbull, A. ed., The Poems of John Davidson. Vol. II, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 3 (1973) Kinghorn, A.M.; Law, A. eds., Poems by Allan Ramsay and Robert Fergusson, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 4 (1974) Gordon, I.A. ed., The Member: an Autobiography. By John Galt, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 5 (1975) MacDonald, R.H. ed., Poems and Prose. By William Drummond of Hawthornden, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 6 (1976) Ruddick, W. ed., Peter’s Letters to his Kinsfolk. By John Gibson Lockhart, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 7 (1977) Gordon, I.A. ed., Selected Short Stories. By John Galt, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 8 (1978) Daiches, D., ed., Selected Political Writings and Speeches.By Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 9 (1979) Hewitt, D. ed., Scott on Himself. A Selection of the autobiographical writings of Sir Walter Scott, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 10 (1981) Reid, D. ed., The Party-Coloured Mind. Prose relating to the conflict of church and state in seventeenth century Scotland, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 11 (1982) Mack, D.S. ed., Selected stories and sketches. By James Hogg, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 12, Edinburgh (1982) Jack, R.D.S.; Lyall, R.J. eds., The Jewel. By Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 13 (1983) Wilson, P.J. -

A History of the Walter Scott Publishing House

A History of the Walter Scott Publishing House by John R. Turner A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of Economic and Social Studies for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Information and Library Studies University of Wales, Aberystwyth 1995 Abstract Sir Walter Scott of Newcastle upon Tyne was bom in poverty and died a millionaire in 1910. He has been almost totally neglected by historians. He owned a publishing company which made significant contributions to cultural life and which has also been almost completely ignored. The thesis gives an account of Scott's life and his publishing business. Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 : The Life of Sir Walter Scott 4 Chapter 2: Walter Scott's Start as a Publisher 25 Chapter 3: Reprints, the Back-Bone of the Business 45 Chapter 4: Editors and Series 62 Chapter 5: Progressive Ideas 112 Chapter 6: Overseas Trade 155 Chapter 7: Final Years 177 Chapter 8: Book Production 209 Chapter 9: Financial Management and Performance of the Company 227 Conclusion 260 Bibliography 271 Appendices List of contracts, known at present, undertaken by Walter Scott, or Walter Scott and Middleton 1 Printing firms employed to produce Scott titles 7 Transcriptions of surviving company accounts 11 Walter Scott, aged 73, from Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, 2nd December 1899, p 7. Introduction The most remarkable fact concerning Walter Scott is his almost complete neglect by historians since his death in 1910. He created a vast business organization based on building and contracting which included work for the major railway companies, the first London underground railway, the construction of docks and reservoirs, ship building, steel manufacture and coal mining.