CAEPR Discussion Paper No.198, CAEPR, ANU, Canberra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Assembly Wednesday 11 November 2020

PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY REPORT OF DEBATES Wednesday 11 November 2020 REVISED EDITION Wednesday 11 November 2020 The Speaker, Ms Hickey, took the Chair at 10 a.m., acknowledged the Traditional People and read Prayers. QUESTIONS Launceston General Hospital - Commission of Inquiry into Child Abuse Claims Ms WHITE question to MINISTER for HEALTH, Ms COURTNEY [12.02 p.m.] Former LGH nurse, Jim Griffin, was charged with heinous child sex offences in October last year. You have been aware of this deeply disturbing case for nearly a year. Why was an independent inquiry only established last month? ANSWER Madam Speaker, I thank the member for her question. As I outlined yesterday to the parliament the safety of our children is the highest priority of this Government and, I would hope, the Tasmanian community. The Premier and I have announced an independent investigation into this matter. As I have outlined both to the parliament and also publicly the terms of reference for this investigation have been informed by expert advice. I am advised that the terms of reference are broad enough to give the investigator the scope she needs to be able to investigate these matters. I know that I, the secretary of the Department of Health, and the Premier are fully committed to ensuring this matter is thoroughly investigated and acting upon the findings of this investigation. With regard to the matter of when information was provided, in terms of advice to the LGH around the suspension of this individual's working with vulnerable people provision, on that day I am advised the staff member was directed to not attend work, and access to the hospital and its information systems were blocked. -

Claiming the Aboriginal Body in Tasmania an Anthropological Study of Repatriation and Redress

Prostor kraj čas 3 Claiming the Aboriginal Body in Tasmania An Anthropological Study of Repatriation and Redress Maja Petrović-Šteger PROSTOR, KRAJ, ČAS 1 PROSTOR, KRAJ, ČAS 3 CLAIMING THE ABORIGINAL BODY IN TASMANIA An Anthropological Study of Repatriation and Redress Maja Petrović-Šteger Photography: Maja Petrović-Šteger Issued by: Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies, ZRC SAZU For the Series: Ivan Šprajc For the Publisher: Oto Luthar Proofreading: James Griffiths Design: Jana Kuharič CIP – Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 572(0.034.2) PETROVIĆ-Šteger, Maja Claiming the aboriginal body in Tasmania [Elektronski vir] : an anthropological study of repatriation and redress / [besedilo, fotografije] Maja Petrović-Šteger. - El. knjiga. - Ljubljana : Založba ZRC, 2013. - (Prostor, kraj, čas, ISSN 2335-4208 ; 3) ISBN 978-961-254-486-7 (pdf) 268860416 Način dostopa (URL): http://zalozba.zrc-sazu.si/p/P03 © 2013, author. This publication is available under the terms of the Creative Commons 2.5 license, which, subject to author's approval, permits noncommercial use but does not allow for any amendments. 2 PROSTOR, KRAJ, ČAS 3 CLAIMING THE ABORIGINAL BODY IN TASMANIA An Anthropological Study of Repatriation and Redress Maja Petrović-Šteger 3 Abstract How do contemporary Tasmanian Aboriginals think of the body? How do they think of the dead body and of their human remains? This work examines the intersection of different cultural, biological and legal concepts of authenticity and belonging as these concepts come into focus as the stake of disputes over Aboriginal remains. In claiming remains, Tasmanians engage a complex set of discursive practices in which the aboriginal body is denoted, performed and negotiated in various ways as the sign of ancestral rights. -

Developing Identity As a Light-Skinned Aboriginal Person with Little Or No

Developing identity as a light-skinned Aboriginal person with little or no community and/or kinship ties. Bindi Bennett Bachelor Social Work Faculty of Health Sciences Australian Catholic University A thesis submitted to the ACU in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy 2015 1 Originality statement This thesis contains no material published elsewhere (except as detailed below) or extracted in whole or part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No parts of this thesis have been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics Committees. This thesis was edited by Bruderlin MacLean Publishing Services. Chapter 2 was published during candidature as Chapter 1 of the following book Our voices : Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work / edited by Bindi Bennett, Sue Green, Stephanie Gilbert, Dawn Bessarab.South Yarra, Vic. : Palgrave Macmillan 2013. Some material from chapter 8 was published during candidature as the following article Bennett, B.2014. How do light skinned Aboriginal Australians experience racism? Implications for Social Work. Alternative. V10 (2). 2 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... -

Forests Agreement Bill 2012, Hobart 5/2/13 (M.Mansell/Maynard/C.Mansell) 1 the Legislative Council Select Committee on the Tasma

THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE TASMANIAN FORESTS AGREEMENT BILL 2012 MET IN COMMITTEE ROOM 1, PARLIAMENT HOUSE, HOBART ON WEDNESDAY 6 FEBRUARY 2013. Mr MICHAEL MANSELL, CHAIR, Ms SARA MAYNARD, TASMANIAN ABORIGINAL CENTRE, AND Mr CLYDE MANSELL, CHAIR, ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL OF TASMANIA, WERE CALLED, MADE THE STATUTORY DECLARATION AND WERE EXAMINED. CHAIR (Mr Harriss) - Welcome. You are familiar with parliamentary committees and that you are protected by parliamentary privilege while in here but not so outside these hearings. Clearly, if asked by the media for comment, you need to be cautious about how you respond to questions, or initiate your own comments with regard to the hearing. Michael first, please? Mr MICHAEL MANSELL - Thank you, Mr Chair, and thanks everybody for giving us the time to present to you a bit of an overview of how the Aboriginal community became involved in the talks about the forestry agreement in the first place, and what we had hoped to gain by that involvement, and where we are now as a result of the things that have taken place. In late 2011 we thought that the forestry agreement would probably require Forestry Tasmania, or the forestry industry, asking for Forest Stewardship Council certification. We understood at the time that was an internationally recognised body, and therefore the certification that came from it attaching to forest products would be of benefit to the industry. I wrote to Forestry Tasmania as a starting point of wanting to have talks with industry. I can't remember the content of the letter, but I think I essentially said that the Aboriginal community had an interest in this. -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 21

Aboriginal History Volume twenty-one 1997 Aboriginal History Incorporated The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Secretary), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), Neil Andrews, Richard Baker, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Bill Humes, Ian Keen, David Johnston, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Diane Smith, Elspeth Young. Correspondents Jeremy Beckett, Valerie Chapman, Ian Clark, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ronald Lampert, Campbell Macknight, Ewan Morris, John Mulvaney, Andrew Markus, Bob Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Roser, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Shaw, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia will be welcomed. Issues include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Editors 1997 Rob Paton and Di Smith, Editors, Luise Hercus, Review Editor and Ian Howie Willis, Managing Editor. Aboriginal History Monograph Series Published occasionally, the monographs present longer discussions or a series of articles on single subjects of contemporary interest. Previous monograph titles are D. Barwick, M. Mace and T. Stannage (eds), Handbook of Aboriginal and Islander History; Diane Bell and Pam Ditton, Law: the old the nexo; Peter Sutton, Country: Aboriginal boundaries and land ownership in Australia; Link-Up (NSW) and Tikka Wilson, In the Best Interest of the Child? Stolen children: Aboriginal pain/white shame, Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus, History in Portraits: biographies of nineteenth century South Australian Aboriginal people. -

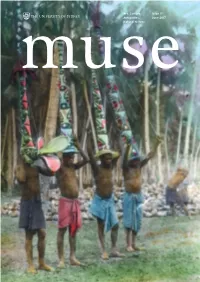

MUSE Issue 17, June 2017

Art. Culture. Issue 17 Antiquities. June 2017 Natural history. New home, new curator, new works A word from the Director, David Ellis In this issue we reveal the first Occupying about 8000 square Fraser, fresh from the British glimpses of the Chau Chak Wing metres, the new building will Museum and digs in the foothills Museum provided by architects triple the previous capacity of of the Jordan Valley. Johnson Pilton Walker. our museums. We reveal two new acquisitions: Situated at the ‘front door’ of the Subject to development approval, photographic works by renowned University, opposite Fisher Library, construction is planned to start artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, purchased the new museum will bring together around November this year. The at auction in New York with funds the collections of the Macleay building is due for completion at from the Morrissey Bequest for the Museum, Nicholson Museum and the end of 2018 with the museum purchase of East Asian material in University Art Gallery under one opening to the public in 2019. memory of Professor Sadler. roof. The Chau Chak Wing Museum will feature state-of-the-art Staff are busy researching and Our Schools Education Program exhibition galleries, object-based developing concepts for new continues to challenge and inspire study rooms, collection care exhibitions, digitising collections through object-based learning facilities and of course a café and conserving works. One of the linked to the schools’ curricula. and museum shop. challenges we are facing is our For many students, it is their first ability, for the first time, to show experience of a university. -

The Roving Party &

The Roving Party & Extinction Discourse in the Literature of Tasmania. Submitted by Rohan David Wilson, BA hons, Grad Dip Ed & Pub. School of Culture and Communication, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. October 2009. Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (Creative Writing). Abstract The nineteenth-century discourse of extinction – a consensus of thought primarily based upon the assumption that „savage‟ races would be displaced by the arrival of European civilisation – provided the intellectual foundation for policies which resulted in Aboriginal dispossession, internment, and death in Tasmania. For a long time, the Aboriginal Tasmanians were thought to have been annihilated, however this claim is now understood to be a fallacy. Aboriginality is no longer defined as a racial category but rather as an identity that has its basis in community. Nevertheless, extinction discourse continues to shape the features of modern literature about Tasmania. The first chapter of this dissertation will examine how extinction was conceived of in the nineteenth-century and traces the influence of that discourse on contemporary fiction about contact history. The novels examined include Doctor Wooreddy’s Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World by Mudrooroo, The Savage Crows by Robert Drewe, Manganinnie by Beth Roberts, and Wanting by Richard Flanagan. The extinctionist elements in these novels include a tendency to euglogise about the „lost race‟ and a reliance on the trope of the last man or woman. The second chapter of the dissertation will examine novels that attempt to construct a representation of Aboriginality without reference to extinction. -

Drysdale Collection

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY CHS 54 THE DRYSDALE COLLECTION Tasmanian Aborigines INTRODUCTION THE RECORDS 1. B C Mollison, Publications 2. B C Mollison, Correspondence 3. B C Mollison, Miscellaneous Material 4. Files on Families 5. R J Drysdale, Correspondence 6. R J Drysdale, Files 7. R J Drysdale, Notebooks 8. General Publications Relating to Tasmanian Aborigines 9. Photographs 10. Background Information Concerning the Collection OTHER SOURCES INTRODUCTION The Drysdale Collection consists of material assembled by B C Mollison and Coral Everitt and published as a series of Tasmanian Aboriginal genealogies from 1974 to 1978 which was lodged with R J Drysdale in 1985. Additional information and material was compiled thereafter by R J Drysdale. Rod Drysdale BA (Aboriginal studies and archaeology), Dip. Forensic Science, was secretary/public relations officer of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Genealogical and Historical Association for five years, researcher responsible for maintenance of the Mollison aboriginal genealogies (1) and chairman of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Education Advisory Council c.1988. The collection was donated to the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in 1995. Access to the collection is restricted and permission must be obtained from the Director of the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery. Reference: 1. Our heritage in history: the sixth Australasian congress on genealogy and heraldry. Official programme, Launceston, 1991 1. B C Mollison, Publications 1/1 B C Mollison, A synopsis of data on Tasmanian Aboriginal people, 2nd edition, to May 1974, with notes 1/2 B C Mollison, Tasmanian Aboriginal genealogies. Part 1. The genealogies of the Eastern Straitsmen, to September 1974 (two copies, one with corrections) 1/3 B C Mollison, Tasmanian Aboriginal genealogies. -

The Assertion of Tasmanian Aboriginality from the 1967 Referendum to Mabo

THE ASSERTION OF TASMANIAN ABORIGINALITY FROM THE 1967 REFERENDUM TO MABO BY Dennis W. Daniels B.A., B.Soe. Admin. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities University of Tasmania, December 1995. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. 'd dd Denn~sDaniels November 1995. Acknowledgments I wish to express my appreciation to Gillian Biscoe, Secretary of the Department of Community and Health Services, for permitting access to relevant material, and for Mary Bailey for facilitating the process. I am particularly grateful to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre for approving the project and to those who granted personal interviews. Personal thanks to Tony Marshall of the Tasmanians section of the State Library. Thesis Abstract The Assertion of Aboriginality in Tasmania From the Referendum to Mabo This paper takes as its starting point a period before the 1967 Referendum which gave full citizenship rights to Australian Aborigines and the Federal Government a mandate over Aboriginal Affairs. During the 40's and 50's the Aboriginal people of Tasmania, represented by the people of Cape Barren Island, stubbornly resisted the assimilation policies of the day. In briefly examining the thesis of resistance as proposed by Lyndall Ryan in her 1981 edition of The Aboriginal Tasmanians, and the proposition that the Government sought to abandon the Island, the paper draws upon new material. -

Aboriginal Society in North West Tasmania:Dispossession And

~boriginal Society in North West Tasmania: Dispossession and Genocide by Ian McFarlane B.A. (Hons) submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania October 2002 Statement of Authorship This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the _University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis. 31 lf?~?.. Zoo-z.. Signed ...... /~ .. ~ .. 'f.-!~.. D at e ..............................t.,. .. Statement of authority of access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. stgne. d............................................... J._ ~~-1-- . 19 March 2002 Abstract Aboriginal Society in North West Tasmania: Dispossession and Genocide As the title indicates this study is restricted to those Aboriginal tribes1 located in the North West region of Tasmania. This approach enables the regional character and diversity of Aboriginal communities to be brought into focus; it also facilitates an . ex:a.miJ,lation of the QJlique process of dispossession that took place in the North West region, an area totally under the control of the Van Diemen's Land Company (VDL Co). Issues dealing with entitlement to ownership and sovereignty will be established by an examination of t~e structure and function of traditional. Aboriginal Societies in the region, as well as the, occupation and use they made of their lands. -

"Tasmania's Palaeo- Aboriginal Population Prior to 1772 Ce"

"TASMANIA'S PALAEO- ABORIGINAL POPULATION PRIOR TO 1772 CE" Barry H. Brimfield 2014 (C/- 17 Mowbray Street, Mowbray 7248, Email: [email protected] Fax: 03 6326 3778 "CONTENTS" 1. Introduction 3 - 4 2. Maps 5 3. Figures 6 4. Abbreviations 7 - 8 5. Glossary 9 - 11 6. Explanations 12 7. Area Conversions 13 8. Calculations & Measurements 14 - 20 9. The Late Pleistocene 21 - 22 10. Holocene Occupied Area 23 11. Environments 24 - 29 12. Occupied Area (recent) 30 - 34 Area occupied to population (Jones (299). 33 - 34 13. Productivity 35 - 56 Dry sclerophyll & Coastal Heath (high productivity). 35 - 36 Within the "Homelands". 36 - 40 Re: Map 3. 40 - 43 Explaining Figure 9. 43 - 47 Should we say eleven not nine "Tribes"? 48 Assets & Liabilities. 48 - 52 Final Comparisons. 52 - 55 Period of Stress. 55 - 56 14. Carrying Capacity 57 - 68 Exploitable Land Area. 59 - 60 Jones (299). 60 - 61 Occupied Area. 61 - 63 Productive Area (Terrestrial). 64 - 66 Inland or Coastal People. 66 - 68 15. Comparisons with Mainland Australia 69 - 73 Victoria. 70 - 73 16. Doubtful Data 74 - 75 17. A Chronological Guide. 76 - 77 18. Reported Numbers 78 - 88 Maritime Explorers (1772 - 1802). 78 - 80 The First Twenty Years (1803 - 1823). 80 - 83 The Last Years (1824 - 1834) 83 - 84 Summary. 85 - 86 Killings. 86 - 88 19. Distant Fires 89 20. Hut Evidence 90 21. Social Structure. 91 - 94 22. Tribal/People Population 95 - 97 Map Comparisons of Jones and Ryan. 96 - 97 23. Complications. 98 - 99 24. Site Density. 100 25. Opinions & Estimates 101 - 103 1 26. -

Inquiry Into the Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal People As Tasmania’S First People

2015 (No. 35) _______________ PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA _______________ HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY STANDING COMMITTEE ON COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Inquiry into the Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal people as Tasmania’s First People ______________ MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE Mr Barnett (Chair) Ms Courtney Mr Jaensch, Ms O’Connor Ms Ogilvie Table of Contents 1 Appointment, terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry.................................3 2 Summary of Findings............................................................................................... 4 Recommendations .............................................................................................7 3 The Constitution of Tasmania ................................................................................. 8 4 Other jurisdictions ................................................................................................... 9 New Zealand..................................................................................................... 13 5 Support for change ................................................................................................ 15 Previous Tasmanian Government support....................................................... 16 Recognition of Tasmania’s history ................................................................... 16 Heritage............................................................................................................20 Absence in Constitution ...................................................................................24