The Assertion of Tasmanian Aboriginality from the 1967 Referendum to Mabo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Assembly Wednesday 11 November 2020

PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY REPORT OF DEBATES Wednesday 11 November 2020 REVISED EDITION Wednesday 11 November 2020 The Speaker, Ms Hickey, took the Chair at 10 a.m., acknowledged the Traditional People and read Prayers. QUESTIONS Launceston General Hospital - Commission of Inquiry into Child Abuse Claims Ms WHITE question to MINISTER for HEALTH, Ms COURTNEY [12.02 p.m.] Former LGH nurse, Jim Griffin, was charged with heinous child sex offences in October last year. You have been aware of this deeply disturbing case for nearly a year. Why was an independent inquiry only established last month? ANSWER Madam Speaker, I thank the member for her question. As I outlined yesterday to the parliament the safety of our children is the highest priority of this Government and, I would hope, the Tasmanian community. The Premier and I have announced an independent investigation into this matter. As I have outlined both to the parliament and also publicly the terms of reference for this investigation have been informed by expert advice. I am advised that the terms of reference are broad enough to give the investigator the scope she needs to be able to investigate these matters. I know that I, the secretary of the Department of Health, and the Premier are fully committed to ensuring this matter is thoroughly investigated and acting upon the findings of this investigation. With regard to the matter of when information was provided, in terms of advice to the LGH around the suspension of this individual's working with vulnerable people provision, on that day I am advised the staff member was directed to not attend work, and access to the hospital and its information systems were blocked. -

Theausfrau~ Unlversmes'review

THEAUSfRAU~ UNlVERSmES'REVIEW 3 SF: or CIo,. Encounter. ot lhe Tertl.ry Kind - Neil Ndason 11 COOfdlnatlon 01 Terti.ry Edue.tlon In Au, tr,ll, - R E pary 15 Fed'f.llntervlntlon In Au.lf,llIn EducaUon: Put, Pr••• nt end Future - W 0 Neal 20 Crl,l, Mln.gemlnl - TBfry Hare 28 The URi",,.lly T•• ch,r Strike. - or Almo.U - Kevlfl HI'1C8 35 Unlversitl •• snd T•• ch" Tr.l"i"g - Alan Barcan 42 Opening Tertl.ry Educ.non - Some Implications 0' Olff.r,nl App,.,.ch.. - Bram Smith .1 The Adjustment 01 Mature Age Unm.triculilled Entflnt, to lIf. I I Intern. I Studlnt • • t the Unlver.lly of New E"gllnd: A Pilot Study - David Walkins 52 Ac.demic St.ft Alloc:.tton Procedure. In In . tltullan. In Au,tr,lI, - ISH GMaon and E POlio 55 ReYle. and letler 10 the Editor PUBLISHED BY FAUSA VOL. 22. 1979. No. 1 ISSN 0042-4560 Journal 01 the Federation of Australian University Siall Associations 1979 Vol. 22 No 1 EDITOR Vestes will In future be published tWice a year, once in April and Mr. J. E. Anwyl, once in November. Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University 01 Melbourne Editorial Policy BUSINESS MANAGER Vestes is the journal 01 the Federation of Australian University Staff Mr, L. B. Wallis, Associations. It aims to be a forum for the discussion of issues con· General Secretary, fronting Australian universities with particular reference to those Federation of Australian University Staft Associalions, matters which concern FAUSA and its member associations. -

The Ascomycota

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 139, 2005 49 A PRELIMINARY CENSUS OF THE MACROFUNGI OF MT WELLINGTON, TASMANIA – THE ASCOMYCOTA by Genevieve M. Gates and David A. Ratkowsky (with one appendix) Gates, G. M. & Ratkowsky, D. A. 2005 (16:xii): A preliminary census of the macrofungi of Mt Wellington, Tasmania – the Ascomycota. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 139: 49–52. ISSN 0080-4703. School of Plant Science, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia (GMG*); School of Agricultural Science, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 54, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia (DAR). *Author for correspondence. This work continues the process of documenting the macrofungi of Mt Wellington. Two earlier publications were concerned with the gilled and non-gilled Basidiomycota, respectively, excluding the sequestrate species. The present work deals with the non-sequestrate Ascomycota, of which 42 species were found on Mt Wellington. Key Words: Macrofungi, Mt Wellington (Tasmania), Ascomycota, cup fungi, disc fungi. INTRODUCTION For the purposes of this survey, all Ascomycota having a conspicuous fruiting body were considered, excluding Two earlier papers in the preliminary documentation of the endophytes. Material collected during forays was described macrofungi of Mt Wellington, Tasmania, were confined macroscopically shortly after collection, and examined to the ‘agarics’ (gilled fungi) and the non-gilled species, microscopically to obtain details such as the size of the -

1992 Assembly 1311

QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE Thursday, 7 May 1992 ASSEMBLY 1311 Thursday, 7 May 1992 Mr Kennett interjected. Ms KIRNER - I actually manage to listen occaSionally in the House, which is more than the Leader of the Opposition does because he does not The SPEAKER (Hon. Ken Coghill) took the chair at agree with the shadow Treasurer on most things. 10.34 a.m. and read the prayer. The Leader of the Opposition is smiling, but it is interesting that when this House debates things like the Auditor-General's report, the opposition QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE spokesman is missing from the House. Where is he now? I cannot see him! Perhaps he has gone to do another radio program to abuse people! Where is STATE ELECTION he? Here he is! Isn't that nice! Mr KENNEIT (Leader of the Opposition) - I Honourable members interjecting. refer the Premier to her often repeated claim of being a community-based politician and I ask: at The SPEAKER - Order! I warn the Leader of the what stage will she put the community's interests OppOSition. He is well aware of the provisions of ahead of her and the government's selfishness, Standing Orders. I expect him to observe the same sorts of standards in this House that he requires in incompetence and dishonesty in managing the meetings that he chairs. affairs of the community she claims to represent by immediately calling an election? Ms KIRNER - No doubt the shadow Treasurer Ms KIRNER (Premier) - I thank the Leader of was out practising his calculated abuse of individuals on the telephone. -

Claiming the Aboriginal Body in Tasmania an Anthropological Study of Repatriation and Redress

Prostor kraj čas 3 Claiming the Aboriginal Body in Tasmania An Anthropological Study of Repatriation and Redress Maja Petrović-Šteger PROSTOR, KRAJ, ČAS 1 PROSTOR, KRAJ, ČAS 3 CLAIMING THE ABORIGINAL BODY IN TASMANIA An Anthropological Study of Repatriation and Redress Maja Petrović-Šteger Photography: Maja Petrović-Šteger Issued by: Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies, ZRC SAZU For the Series: Ivan Šprajc For the Publisher: Oto Luthar Proofreading: James Griffiths Design: Jana Kuharič CIP – Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 572(0.034.2) PETROVIĆ-Šteger, Maja Claiming the aboriginal body in Tasmania [Elektronski vir] : an anthropological study of repatriation and redress / [besedilo, fotografije] Maja Petrović-Šteger. - El. knjiga. - Ljubljana : Založba ZRC, 2013. - (Prostor, kraj, čas, ISSN 2335-4208 ; 3) ISBN 978-961-254-486-7 (pdf) 268860416 Način dostopa (URL): http://zalozba.zrc-sazu.si/p/P03 © 2013, author. This publication is available under the terms of the Creative Commons 2.5 license, which, subject to author's approval, permits noncommercial use but does not allow for any amendments. 2 PROSTOR, KRAJ, ČAS 3 CLAIMING THE ABORIGINAL BODY IN TASMANIA An Anthropological Study of Repatriation and Redress Maja Petrović-Šteger 3 Abstract How do contemporary Tasmanian Aboriginals think of the body? How do they think of the dead body and of their human remains? This work examines the intersection of different cultural, biological and legal concepts of authenticity and belonging as these concepts come into focus as the stake of disputes over Aboriginal remains. In claiming remains, Tasmanians engage a complex set of discursive practices in which the aboriginal body is denoted, performed and negotiated in various ways as the sign of ancestral rights. -

Voices of Aboriginal Tasmania Ningina Tunapri Education

voices of aboriginal tasmania ningenneh tunapry education guide Written by Andy Baird © Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery 2008 voices of aboriginal tasmania ningenneh tunapry A guide for students and teachers visiting curricula guide ningenneh tunapry, the Tasmanian Aboriginal A separate document outlining the curricula links for exhibition at the Tasmanian Museum and the ningenneh tunapry exhibition and this guide is Art Gallery available online at www.tmag.tas.gov.au/education/ Suitable for middle and secondary school resources Years 5 to 10, (students aged 10–17) suggested focus areas across the The guide is ideal for teachers and students of History and Society, Science, English and the Arts, curricula: and encompasses many areas of the National Primary Statements of Learning for Civics and Citizenship, as well as the Tasmanian Curriculum. Oral Stories: past and present (Creation stories, contemporary poetry, music) Traditional Life Continuing Culture: necklace making, basket weaving, mutton-birding Secondary Historical perspectives Repatriation of Aboriginal remains Recognition: Stolen Generation stories: the apology, land rights Art: contemporary and traditional Indigenous land management Activities in this guide that can be done at school or as research are indicated as *classroom Activites based within the TMAG are indicated as *museum Above: Brendon ‘Buck’ Brown on the bark canoe 1 voices of aboriginal tasmania contents This guide, and the new ningenneh tunapry exhibition in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, looks at the following -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

Hutchinsmbdec2005.Pdf

Magenta ANDBlack Print Post approved PP 739016/00028 Hutchins School Newsletter December 2005 Our Community There are events during the year School) was inaugurated in Tasmania that express the importance and the to afford a means of training up the depth and breadth of our Hutchins youth of Tasmania…” Community. I feel a strong sense of community As people’s connections with and tradition when flanked by some churches lessen, the School is asked 700 boys singing in the Cathedral. to hold funeral services for its current students and its Old Boys. We are The farewelling of our Leavers by very happy to do this and glad that the ELC choir brings a tear to the the School can provide support in eye because the journey for our such sad and stressful times. Father Year Twelves in the School is just John is a tower of strength on such concluding, and they are brought face occasions and his role is greatly to face with where they started all appreciated. those years ago. The ELC boys are these nights are people who have young, perhaps a little uncertain and touched and been touched by our We broke with tradition this year and yet to experience that journey. It is community. Old Boys, parents, moved the Anniversary Service from the juxtaposition of the younger boys grandparents, friends, staff, students Sunday evening to a time during with all their youthful exuberance and specially invited guests come the school day. While this may and the older boys who have lost together to celebrate our community. -

27 March 2012 (Extract from Book 4)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 27 March 2012 (Extract from book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable ALEX CHERNOV, AC, QC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier and Minister for the Arts................................... The Hon. E. N. Baillieu, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Police and Emergency Services, Minister for Bushfire Response, and Minister for Regional and Rural Development.................................................. The Hon. P. J. Ryan, MP Treasurer........................................................ The Hon. K. A. Wells, MP Minister for Innovation, Services and Small Business, and Minister for Tourism and Major Events...................................... The Hon. Louise Asher, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Finance........................... The Hon. R. W. Clark, MP Minister for Employment and Industrial Relations, and Minister for Manufacturing, Exports and Trade ............................... The Hon. R. A. G. Dalla-Riva, MLC Minister for Health and Minister for Ageing.......................... The Hon. D. M. Davis, MLC Minister for Sport and Recreation, and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs . The Hon. H. F. Delahunty, MP Minister for Education............................................ The Hon. M. F. Dixon, MP Minister for Planning............................................ -

Developing Identity As a Light-Skinned Aboriginal Person with Little Or No

Developing identity as a light-skinned Aboriginal person with little or no community and/or kinship ties. Bindi Bennett Bachelor Social Work Faculty of Health Sciences Australian Catholic University A thesis submitted to the ACU in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy 2015 1 Originality statement This thesis contains no material published elsewhere (except as detailed below) or extracted in whole or part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No parts of this thesis have been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics Committees. This thesis was edited by Bruderlin MacLean Publishing Services. Chapter 2 was published during candidature as Chapter 1 of the following book Our voices : Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work / edited by Bindi Bennett, Sue Green, Stephanie Gilbert, Dawn Bessarab.South Yarra, Vic. : Palgrave Macmillan 2013. Some material from chapter 8 was published during candidature as the following article Bennett, B.2014. How do light skinned Aboriginal Australians experience racism? Implications for Social Work. Alternative. V10 (2). 2 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... -

Paradoxes of Protection Evolution of the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service and National Parks and Reserved Lands System

Paradoxes of Protection Evolution of the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service and National Parks and Reserved Lands System By Dr Louise Crossley May 2009 A Report for Senator Christine Milne www.christinemilne.org.au Australian Greens Cover image: Lake Gwendolen from the track to the summit of Frenchmans Cap, Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Photo: Matt Newton Photography Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. 1 1. THE INITIAL ESTABLISHMENT OF PARKS AND RESERVES; UTILITARIANS VERSUS CONSERVATIONISTS 1915-1970....................................................................... 3 1.1 The Scenery Preservation Board as the first manager of reserved lands ............................................................ 3 1.2 Extension of the reserved lands system ................................................................................................................... 3 1.3The wilderness value of wasteland ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Inadequacies of the Scenery Protection Board ...................................................................................................... 4 2. THE ESTABLISHMENT AND ‘GLORY DAYS’ OF THE NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE SERVICE 1971-81 ........................................................................................... 6 2.1 The demise of the Scenery Preservation Board and the Lake Pedder controversy -

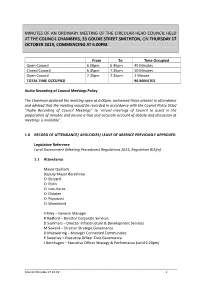

Minutes of an Ordinary Meeting of the Circular Head Council Held at the Council Chambers, 33 Goldie Street Smithton, on Thursday 17 October 2019, Commencing at 6.00Pm

MINUTES OF AN ORDINARY MEETING OF THE CIRCULAR HEAD COUNCIL HELD AT THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, 33 GOLDIE STREET SMITHTON, ON THURSDAY 17 OCTOBER 2019, COMMENCING AT 6.00PM. From To Time Occupied Open Council 6.00pm 6.45pm 45 Minutes Closed Council 6.45pm 7.35pm 50 Minutes Open Council 7.35pm 7.36pm 1 Minute TOTAL TIME OCCUPIED 96 MINUTES Audio Recording of Council Meetings Policy The Chairman declared the meeting open at 6.00pm, welcomed those present in attendance and advised that the meeting would be recorded in accordance with the Council Policy titled “Audio Recording of Council Meetings” to ‘record meetings of Council to assist in the preparation of minutes and ensure a true and accurate account of debate and discussion at meetings is available’. 1.0 RECORD OF ATTENDANCE/ APOLOGIES/ LEAVE OF ABSENCE PREVIOUSLY APPROVED Legislative Reference Local Government (Meeting Procedures) Regulations 2015; Regulation 8(2)(a) 1.1 Attendance Mayor Quilliam Deputy Mayor Berechree Cr Blizzard Cr Ettlin Cr Ives-Heres Cr Oldaker Cr Popowski Cr Woodward S Riley – General Manager R Radford – Director Corporate Services D Summers – Director Infrastructure & Development Services M Saward – Director Strategic Governance D Mainwaring – Manager Connected Communities K Sweeney – Executive Officer Civic Governance J Bernhagen – Executive Officer Strategy & Performance (until 6.20pm) ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Council Minutes 17 10 19 1 1.2 Prayers Pastor Matt Nuske from Dreambuilders Church led the meeting in prayer. 1.3 Leave of Absence(s) previously approved Nil 1.4 Apologies Cr Kay 2.0 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING Legislative Reference Local Government (Meeting Procedures) Regulations 2015; Regulation 8(2) (b) MOVED: CR POPOWSKI SECONDED: CR IVES-HERES That the Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting 19 September 2019, a copy of which having previously been circulated to Councillors prior to the meeting, be confirmed as a true record.