Theatre Archive Project: Scripts Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E.M. Parry Designer

E.M. Parry Designer E.M. Parry is a transgender, trans-disciplinary artist and theatre- maker, best known for theatre design, specialising in work which centres queer bodies and narratives. They are an Associate Artist at Shakespeare’s Globe, a Linbury Prize Finalist, winner of the Jocelyn Herbert Award, and shared an Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement as part of the team behind Rotterdam, for which they designed set and costumes. Agents Dan Usztan Assistant [email protected] Charlotte Edwards 0203 214 0873 [email protected] 0203 214 0924 Credits In Development Production Company Notes DORIAN Reading Rep Dir. Owen Horsley 2021 Written by Phoebe Eclair-Powell and Owen Horsley Theatre Production Company Notes STAGING PLACES: UK Victoria and Albert Museum Designs included in exhibition DESIGN FOR PERFORMANCE 2019 AS YOU LIKE IT Shakespeare's Globe Revival of 2018 production 2019 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE STRANGE New Vic Theatre Dir. Anna Marsland UNDOING OF By David Grieg PRUDENCIA HART 2019 ROTTERDAM Hartshorn Hook UK tour of Olivier Award-winning production 2019 TRANSLYRIA Sogn og Fjordane Teater, Dir. Frode Gjerlow 2019 Norway By William Shakespeare & Frode Gjerlow GRIMM TALES Unicorn Theatre Dir. Kirsty Housley 2018 Adapted from Philip Pullman's Grimm Tales by Philip Wilson SKETCHING Wilton's Music Hall Dir. Thomas Hescott 2018 By James Graham AS YOU LIKE IT Shakespeare's Globe Dir. Federay Holmes and Elle While 2018 By William Shakespeare HAMLET Shakespeare's Globe Dir. -

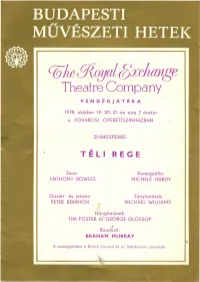

Q;;Heg{Qyalgxchange

q;;he g{qyalgxchange Theatre Company VENDÉGJÁTÉKA 1978. október 19, 20, 21-én este 7 órakor a FŐVÁROSIOPERETTSZíNHÁZBAN SHAKESPEARE: , TELI REGE Zene: Koreográfia: ANTHONY BOWLES MICHELE HARDY Díszlet- és jelmez: Fényhatások: PETER B'ENNION MICHAEL WILLIAMS Hanghatások: TIM FOSTER és GEORGE GLOSSOP ,. Rendező: BRAHAM MURRAY A vendégjátékot a British Council és az Interkoncert szervezte. Szereplők Leontes, Szicília királya James Maxwell MamiIlius, a fia ... Sarah Webb CamilIo Jeffrey Wickham Antigonus Morris Perry szicíliai nemesurak Cliomenes, Peter Guinness Dion Paul Clayton Polixenes, Bohémia királya John Turner Florizel, a fia Richard Durden Archidamus, bohémiai nemesúr Peter Guinness Greg pásztor, akit Perdita atyjának vélnek Harold Goodwin I I Bangó, a fia ... lan Hastings • Autolycus, csavargó Harry Landis Hajós ... Keith Taylor Tömlöcőr Keith Taylor Hermione, Leontes felesége Helen Ryan Perdita, Leontes és Hermione lánya Jacqueline Tong Paulina, Antigonus felesége ... .. Dilys Hamlett Emilia, Hermione udvarhölgye Angela Rooks Philippa Howell Mopsa, Dorcas parasztlányok Chloe Sciennon Knight Moritell, Keith Taylor. Főurak, nemesurak, hölgyek, tisztek, Nicolas Gecks, Peter Guiness szolgák, pásztorok és pásztorlányok Jon Glentoran Történik részint Szicíliában, részínt Bohémiában. , THE ROYAL EXCHANGE THEATRE COMPANY MANCHESTER A színház jelenlegi társulatának "őse" az az együttes, amely 1959-ben a lan- da ni Lyric Theatre-ben több darabot mutatott be és olyan rendezőkkel, terve- zőkkel és színészekkel büszkélkedett, akik Michel Sein-Denis keze alatt nőttek művésszé és tanultak az Old Vic lsl.olójóbc n. Mindenféle anyagi támogatás nélkül izgalmas előadásokat tudtak teremteni, elsősorban európai drámaírók műveiből, mint Büchner vagy Strindberg. A rnúsornok már csak azért is ~ikere volt, mert Angliában abban az időben nemigen nyúltak az európai klcssziku- sokhoz. A színészeket is igen nagyra értékelte a kritika, többek között Patrick Wym<,rkot, Mai Zetterlinget és Rupert Daviest. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós-Graduação Em Letras/Inglês E Literatura Correspondente

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS/INGLÊS E LITERATURA CORRESPONDENTE SHAKESPEARE IN THE TUBE: THEATRICALIZING VIOLENCE IN BBC’S TITUS ANDRONICUS FILIPE DOS SANTOS AVILA Supervisor: Dr. José Roberto O’Shea Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras/Inglês e Literatura Correspondente da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina em cumprimento parcial dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS FLORIANÓPOLIS MARÇO/2014 Agradecimentos CAPES pelo apoio financeiro, sem o qual este trabalho não teria se desenvolvido. Espero um dia retribuir, de alguma forma, o dinheiro investido no meu desenvolvimento intelectual e profissional. Meu orientador e, principalmente, herói intelectual, professor José Roberto O’Shea, por ter apoiado este projeto desde o primeiro momento e me guiado com sabedoria. My Shakespearean rivals (no sentido elisabetano), Fernando, Alex, Nicole, Andrea e Janaína. Meus colegas do mestrado, em especial Laísa e João Pedro. A companhia de vocês foi de grande valia nesses dois anos. Minha grande amiga Meggie. Sem sua ajuda eu dificilmente teria terminado a graduação (e mantido a sanidade!). Meus professores, especialmente Maria Lúcia Milleo, Daniel Serravalle, Anelise Corseuil e Fabiano Seixas. Fábio Lopes, meu outro herói intelectual. Suas leituras freudianas, chestertonianas e rodrigueanas dos acontecimentos cotidianos (e da novela Avenida Brasil, é claro) me influenciaram muito. Alguns russos que mantém um site altamente ilegal para download de livros. Sem esse recurso eu honestamente não me imaginaria terminando essa dissertação. Meus amigos. Vocês sabem quem são, pois ouviram falar da dissertação mais vezes do que gostariam ao longo desses dois anos. Obrigado pelo apoio e espero que tenham entendido a minha ausência. -

Ugly Rumours: a Mockumentary Beyond the Simulated Reality

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 4, Issue 11, 2017, PP 22-29 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) Ugly Rumours: A Mockumentary beyond the Simulated Reality Kağan Kaya Faculty of Letters English Language and Literature, Cumhuriyet University, Turkey *Corresponding Author: Kağan Kaya, Faculty of Letters English Language and Literature, Cumhuriyet University, Turkey ABSTRACT Ugly Rumours was the name of a rock band which was co-founded by Tony Blair when he was a student at St John's College, Oxford. In the hands of two British dramatists, Howard Brenton and Tariq Ali, it transformed into a name of the satirical play against New Labour at the end of the last century. The play encapsulates the popular political struggle of former British leaders, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. However, this work aims at analysing some sociological messages of the play in which Brenton and Ali tell on media and reality in the frame of British politics and democracy. Through the analyses of this unfocussed local mock-epic, it precisely points out ideas reflecting the real which is manipulated for the sake of power in a democratic atmosphere. Thereof it takes some views on Simulation Theory of French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard as the basement of analyses. According to Baudrillard, our perception of things has become corrupted by a perception of reality that never existed. He believes that everything changes with the device of simulation. Hyper-reality puts an end to the real as referential by exalting it as model. (Baudrillard, 1983:21, 85) That is why, establishing a close relationship with the play, this work digs deeper into the play through the ‘Simulation Theory’ and analysing characters who are behind the unreal, tries to display the role of Brenton and Ali’s drama behind the fact. -

Laughing out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey's Girls Like That And

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 19 | 2019 Rethinking Laughter in Contemporary Anglophone Theatre Laughing Out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey’s Girls Like That and Other Plays for Teenagers (2016) Claire Hélie Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/20064 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.20064 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Printed version Date of publication: 7 October 2019 Electronic reference Claire Hélie, “Laughing Out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey’s Girls Like That and Other Plays for Teenagers (2016)”, Miranda [Online], 19 | 2019, Online since 09 October 2019, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/20064 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ miranda.20064 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Laughing Out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey’s Girls Like That and Other Plays... 1 Laughing Out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey’s Girls Like That and Other Plays for Teenagers (2016) Claire Hélie 1 Evan Placey1 is a Canadian-British playwright who writes for young audiences; but unlike playwrights such as Edward Bond, Dennis Kelly or Tim Crouch, he writes for young audiences only. Some of his plays target young children, like WiLd! (2016), the monologue of an 8-year-old boy with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), other young adults, like Consensual (2015), which explores the grey area between rape and consent. His favourite audience remain teenagers and four of the plays he wrote for them were collected in Girls Like That and Other Plays for Teenagers in 2016. -

The Use of Brechtian Devices in Howard Brenton's Hitler

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature English Language and Literature THE USE OF BRECHTIAN DEVICES IN HOWARD BRENTON’S HITLER DANCES, MAGNIFICENCE AND THE ROMANS IN BRITAIN Ozan Günay AYGÜN Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2019 THE USE OF BRECHTIAN DEVICES IN HOWARD BRENTON’S HITLER DANCES, MAGNIFICENCE AND THE ROMANS IN BRITAIN Ozan Günay AYGÜN Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature English Language and Literature Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2019 In memory of my aunt Zehra Aygün, who always treated us as one of her own. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. A. Deniz Bozer, for her patience, support and invaluable academic guidance. She was always understanding throughout the writing process of this thesis, and she encouraged me in times of stress and guided me with her wisdom. Without her, I would not be able to complete this thesis and I am most grateful and honored to have studied under her supervision. I am also indebted to the head of our department, Prof. Dr. Burçin Erol, for her patient guidance whenever I was unsure of how to proceed with my studies during my time as a student at Hacettepe University. I would also like to extend my gratitude to the distinguished members of the jury, Prof. Dr. Aytül Özüm, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Şebnem Kaya, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sıla Şenlen Güvenç, Asst. Prof. Dr. İmren Yelmiş and Asst. Prof. Dr. F. Neslihan Ekmekçioğlu for their valuable feedback and critical comments which had an immense effect in the development of this thesis. -

Europe at the Crossroads

Europe at the Crossroads Zinnie Harris’s How to Hold Your Breath Janine HAUTHAL Vrije Universiteit Brussel1 “Where Were All the Plays About Brexit?”2: Europe and/in British Theatre When, on the morning of the 24th of June 2016, it turned out that the majority of the British had voted for ‘Brexit’ in the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, theatre critic Dominic Cavendish wondered publicly on his twitter account why British theatre had failed to tackle this momentous decision proactively. However, as fellow critic Matt Trueman suggested in response: “We might not have seen Brexit: the Musical – and nor would we want to – but many playwrights have explored the social and political factors that fed into the result” (n. pag.). Indeed, since the 1990s, a number of British plays have been set in or concerned with Europe, and Eastern Europe in particular, as e.g. Caryl Churchill’s Mad Forest (1990), Tariq Ali and Howard Brenton’s Moscow Gold (1990), David Greig’s Europe (1994), Sarah Kane’s Blasted (1995), Timberlake Wertenbaker’s The Break of Day (1995) as well as David Edgar’s trilogy The Shape of the Table (1990), Pentecost (1994), and The Prisoner’s Dilemma (2001) demonstrate. The majority of these plays were premiered between 1990 and 1995, i.e. in the years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the disintegration of the ‘Eastern bloc’ and the collapse of communism. They are therefore frequently referred to as ‘post-wall plays’.3 Depicting 1 The research for this article was financed by the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO). -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Current feminist theatre scholarship tends to use the term ‘heteronormative’. The predominant use of the term ‘heterosexist’ in this study draws directly from black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde’s notion of ‘Heterosexism [as] the belief in the inherent superiority of one pattern of loving and thereby its right to dominance’ (Lorde, 1984, p. 45). 2. See Diana Fuss, Essentially Speaking: Feminism, Nature and Difference (London: Routledge, 1989) for summaries and discussions of the essen- tialism/constructionism debates. 3. See, for example, Elaine Aston, An Introduction to Feminism and Theatre (London: Routledge, 1995); Elaine Aston, Feminist Views on the English Stage: Women Playwrights, 1990–2000 (Cambridge: CUP, 2003); Mary F. Brewer, Race, Sex and Gender in Contemporary Women’s Theatre: The Construction of ‘Woman’ (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 1999); Lizbeth Goodman, Contemporary Feminist Theatres: To Each Her Own (London: Routledge, 1993); and Gabriele Griffin Contemporary Black and Asian Women Playwrights in Britain (Cambridge: CUP, 2003). 4. See, for example, Susan Croft, ‘Black Women Playwrights in Britain’ in Trevor R. Griffiths and Margaret Llewellyn Jones, eds, British and Irish Women Dram- atists Since 1968 (Buckingham: OUP, 1993); Mary Karen Dahl, ‘Postcolonial British Theatre: Black Voices at the Center’ in J. Ellen Gainor, ed., Imperi- alism and Theatre: Essays on World Theatre, Drama and Performance (London: Routledge, 1995); Sandra Freeman, Putting Your Daughters on the Stage: Lesbian Theatre from -

Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, Written by Christopher M

BIOGRAPHY CAST IN IRONY: CAVEATS, STYLIZATION, AND INDETERMINACY IN THE BIOGRAPHICAL HISTORY PLAYS OF TOM STOPPARD AND MICHAEL FRAYN by CHRISTOPHER M. SHONKA B.A. Creighton University, 1997 M.F.A. Temple University, 2000 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre 2010 This thesis entitled: Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, written by Christopher M. Shonka, has been approved for the Department of Theatre Dr. Merrill Lessley Dr. James Symons Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Shonka, Christopher M. (Ph.D. Theatre) Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn Thesis directed by Professor Merrill J. Lessley; Professor James Symons, second reader Abstract This study examines Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn‘s incorporation of epistemological themes related to the limits of historical knowledge within their recent biography-based plays. The primary works that are analyzed are Stoppard‘s The Invention of Love (1997) and The Coast of Utopia trilogy (2002), and Frayn‘s Copenhagen (1998), Democracy (2003), and Afterlife (2008). In these plays, caveats, or warnings, that illustrate sources of historical indeterminacy are combined with theatrical stylizations that overtly suggest the authors‘ processes of interpretation and revisionism through an ironic distancing. -

History in the Age of Fracture

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 The Politics of Time in Recent English History Plays Jay M. Gipson-King Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVSERITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE, AND DANCE HISTORY IN THE AGE OF FRACTURE: THE POLITICS OF TIME IN RECENT ENGLISH HISTORY PLAYS By JAY M. GIPSON-KING A Dissertation submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester: 2010 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Jay M. Gipson-King defended on October 27, 2010. Mary Karen Dahl Professor Directing Dissertation James O‘Rourke University Representative Natalya Baldyga Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to the vast number of people who made this dissertation possible. First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee chair, Mary Karen Dahl, for her guidance throughout this project and my graduate career; it is due to her that I developed my love of contemporary British theatre in the first place. I also thank committee member Natalya Baldyga, for sharing her love of the Futurists; University Representative James O‘Rourke, for his insightful reading of the manuscript and his outside perspective; former committee member Caroline Joan S. (―Kay‖) Picart, whose early feedback helped shape the structure the prospectus; and former committee member Amit Rai, who introduced me to affect theory. -

David Horovitch

David Horovitch FILM Rebecca Coroner Working Title Ben Wheatley Summerland Albert Shoebox Films Jessica Swale The Nun Cardinal Conroy New Line Corin Hardy Marrowbone Redmond Tele5 Sergio G Sanchez HHHH Admiral Hansen Adama Pictures Cedric Jimenez The Sense of an Ending Headmaster BBC Films Ritesh Batra The Chamber The Captain Chamber Films Ben Parker The Infiltrator Saul Mineroff Good Films Ltd Brad Fuman Mr. Turner Dr. Price Film 4 Mike Leigh Blink (Short) Harry Starfish Films Paul Wilkins Young Victoria Sir James Clark Initial Entertainment Group Jean Marc Vallee Veiled Michael Dan Susman In Your Dreams Edward Shoreline Entertainment Gary Sinyor WASP 06 Pop Jelly Roll Prods Woody Allen 102 Dalmations Doctor Pavlov Walt Disney Kevin Lima Max MaxÍs Father Pathú Menno Meyjes One of the Hollywood Ten Ben Margolis Bloom Street Prods Karl Francis Soloman and Gaenor Isaac APT Film & Television Paul Morrison Paper Marriage Frank Haddow Mark Forstater Krzysztof Lang Dirty Dozen: The Deadly Mission Pierre Claudel MGM Lee H. Katzin An Unsuitable Job for a Woman Sergeant Maskell Castle Hill Prods Inc. Christopher Petit TELEVISION Dad's Army Colonel Square UKTV Various Untitled NPX Project Judge Raptor Pictures LTD Various Directors Doctors 2018 Harry Brook BBC Various Churchill's Secret Affairs Jock Colville Channel 4 Holby City Rabbi Stein BBC Various Doctors Gerald Dunlop BBC Various The Assets US Ambassador ABC Jeff T.Thomas/ Rudy Bednar/ Adam Feinstein Casualty Morris BBC Paul Murphy Heartbeat Douglas ITV Roger Bamford Trial & Retribution Alistair Darwin ITV Ben Ross Casualty 1907 Lord Rothchild BBC Bryn Higgins Donovan Palmer Thornhill Granada Ciaran Donnelly Dirty War Lambert BBC Daniel Percival Goodbye Mr.