Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliography of Drama in English by Caribbean Writers, to 2010 Compiled By

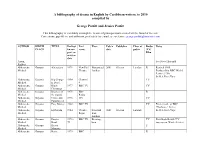

A bibliography of drama in English by Caribbean writers, to 2010 compiled by George Parfitt and Jessica Parfitt This bibliography is inevitably incomplete. A note of principal sources used will be found at the end. Corrections, gap-fillers, and additions, preferably by e-mail, are welcome: [email protected] AUTHOR BIRTH TITLE Earliest Perf Place Pub’n Publisher Place of Radio Notes PLACE known venue date pub’n /TV/ perf. or Film written date Aaron, See Steve Hyacinth Philbert Abbensetts, Guyana Alterations 1978 New End Hampstead 2001 Oberon London R Revised 1985. Michael Theatre London Produced for BBC World Service 1980. In M.A.Four Plays Abbensetts, Guyana Big George 1994 Channel TV Michael Is Dead 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Black 1977 BBC TV TV Michael Christmas Abbensetts, Guyana Brothers of 1978 BBC R Michael the Sword Radio Abbensetts, Guyana Crime and 1976 ITV TV Michael Punishment Abbensetts, Guyana Easy Money 1982 BBC TV TV First episode of BBC Michael ‘Playhouse’ Series Abbensetts, Guyana El Dorado 1984 Theatre Stratford 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Royal East, London Abbensetts, Guyana Empire 1978 - BBC TV Birming- TV First black British T.V. Michael Road 79 ham soap opera. Wrote 2 series Abbensetts, Guyana Heavy F Michael Manners Abbensetts, Guyana Home 1975 BBC R Michael Again Radio Abbensetts, Guyana In The 1981 Hamp- London 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Mood stead Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Inner City 1975 Granada Manchest- TV Episode One of ‘Crown Michael Blues TV er Court’ Abbensetts, Guyana Little 1994 Channel TV 4-part drama Michael Napoleons 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Outlaw 1983 Arts Leicester Michael Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Roadrunner 1977 ITV TV First episode of ‘ITV Michael Playhouse’ series Abbensetts, Guyana Royston’s 1978 BBC TV Birming- 1988 Heinemann London TV Episode 4, Series 1 of Michael Day ham Empire Road. -

Gregory Clarke Sound Designer

Gregory Clarke Sound Designer Agents Giles Smart Assistant Ellie Byrne [email protected] +44 (020 3214 0812 Credits In Development Production Company Notes THE HOUSE OF SHADES Almeida By Beth Steel 2020 Dir. Blanche McIntyre ALL OF US National Theatre By Francesca Martinez 2020 Dir. Ian Rickson THE REALISTIC JONESES Theatre Royal Bath By Will Eno 2020 Dir. Simon Evans Theatre Production Company Notes THE BOY FRIEND Menier Chocolate Factory Book, Music and Lyrics by Sandy Wilson 2020 Dir. Matthew White THE WIZARD OF OZ Chichester Festival Adapted by John Kane from the motion 2019 Theatre picture screenplay A DOLL'S HOUSE Lyric Hammersmith By Henrik Ibsen in a new adaptation by 2019 Tanika Gupta Dir. Rachel O’Riordan. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE SECRET DIARY OF Ambassadors Theatre Based on the novel by Sue Townsend ADRIAN MOLE AGED 13 3/4 Dir. Luke Sheppard Book & Lyrics by 2019 Jake Brunger, Music & Lyrics by Pippa Cleary Transfer of Menier Chocolate Factory production THE BRIDGES OF MADISON Menier Chocolate Factory Book by Marsha Norman COUNTY Music & Lyrics by Jason Robert Brown 2019 Based on the novel by Robert James Waller Direction Trevor Nunn THE BEACON Druid By Nancy Harris 2019 Dir. Garry Hynes RICHARD III Druid / Lincoln Center NYC By William Shakespeare 2019 Dir. Garry Hynes ORPHEUS DESCENDING Theatr Clwyd / Menier By Tennessee Williams 2019 Chocolate Factory Dir. Tamara Harvey THE BAY AT NICE Menier Chocolate Factory By David Hare 2019 Dir. -

LATE COMPANY by Jordan Tannahill

Press Information ! ! VIBRANT NEW WRITING | UNIQUE REDISCOVERIES Spring-Summer Season 2017 | April–July 2017 The European premiere LATE COMPANY by Jordan Tannahill. Directed by Michael Yale. Designed by Zahra Mansouri. Lighting by Nic Farman. Sound by Christopher Prosho. Presented by Stage Traffic Productions in association with Neil McPherson for the Finborough Theatre. Cast: Todd Boyce. David Leopold. Alex Lowe. Lucy Robinson. Lisa Stevenson. “When you wake up in a cold sweat at night and you think someone is watching you, well it’s me. I’m watching you. And that cold sweat on your body, those are my tears…“ As part of the Finborough Theatre’s celebrations of Canada’s 150th birthday, the European debut of “the hottest name in Canadian theatre”, Jordan Tannahill, with the European premiere of Late Company playing at the Finborough Theatre for a four week limited season on Tuesday, 25 May 2017 (Press Nights: Thursday, 27 April 2017 and Friday, 28 April 2017 at 7.30pm). One year after the suicide of their teenage son, Debora and Michael sit down to dinner with their son’s bully and his parents. Closure is on the menu, but accusations are the main course as good intentions are gradually stripped away to reveal layers of parental, sexual, and political hypocrisy – at a dinner party where grief is the loudest guest. Written with sensitivity and humour, Late Company explores restorative justice, cyber bullying, and is both a timely and timeless meditation on a parent’s struggle to comprehend the monstrous and unknown in their child. Playwright Jordan Tannahill has been described as “the future of Canadian theatre” by NOW Magazine. -

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

E.M. Parry Designer

E.M. Parry Designer E.M. Parry is a transgender, trans-disciplinary artist and theatre- maker, best known for theatre design, specialising in work which centres queer bodies and narratives. They are an Associate Artist at Shakespeare’s Globe, a Linbury Prize Finalist, winner of the Jocelyn Herbert Award, and shared an Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement as part of the team behind Rotterdam, for which they designed set and costumes. Agents Dan Usztan Assistant [email protected] Charlotte Edwards 0203 214 0873 [email protected] 0203 214 0924 Credits In Development Production Company Notes DORIAN Reading Rep Dir. Owen Horsley 2021 Written by Phoebe Eclair-Powell and Owen Horsley Theatre Production Company Notes STAGING PLACES: UK Victoria and Albert Museum Designs included in exhibition DESIGN FOR PERFORMANCE 2019 AS YOU LIKE IT Shakespeare's Globe Revival of 2018 production 2019 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE STRANGE New Vic Theatre Dir. Anna Marsland UNDOING OF By David Grieg PRUDENCIA HART 2019 ROTTERDAM Hartshorn Hook UK tour of Olivier Award-winning production 2019 TRANSLYRIA Sogn og Fjordane Teater, Dir. Frode Gjerlow 2019 Norway By William Shakespeare & Frode Gjerlow GRIMM TALES Unicorn Theatre Dir. Kirsty Housley 2018 Adapted from Philip Pullman's Grimm Tales by Philip Wilson SKETCHING Wilton's Music Hall Dir. Thomas Hescott 2018 By James Graham AS YOU LIKE IT Shakespeare's Globe Dir. Federay Holmes and Elle While 2018 By William Shakespeare HAMLET Shakespeare's Globe Dir. -

Albion Full Cast Announced

Press release: Thursday 2 January The Almeida Theatre announces the full cast for its revival of Mike Bartlett’s Albion, directed by Rupert Goold, following the play’s acclaimed run in 2017. ALBION by Mike Bartlett Direction: Rupert Goold; Design: Miriam Buether; Light: Neil Austin Sound: Gregory Clarke; Movement Director: Rebecca Frecknall Monday 3 February – Saturday 29 February 2020 Press night: Wednesday 5 February 7pm ★★★★★ “The play that Britain needs right now” The Telegraph This is our little piece of the world, and we’re allowed to do with it, exactly as we like. Yes? In the ruins of a garden in rural England. In a house which was once a home. A woman searches for seeds of hope. Following a sell-out run in 2017, Albion returns to the Almeida for four weeks only. Joining the previously announced Victoria Hamilton (awarded Best Actress at 2018 Critics’ Circle Awards for this role) and reprising their roles are Nigel Betts, Edyta Budnik, Wil Coban, Margot Leicester, Nicholas Rowe and Helen Schlesinger. They will be joined by Angel Coulby, Daisy Edgar-Jones, Dónal Finn and Geoffrey Freshwater. Mike Bartlett’s plays for the Almeida include his adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s Vassa, Game and the multi-award winning King Charles III (Olivier Award for Best New Play) which premiered at the Almeida before West End and Broadway transfers, a UK and international tour. His television adaptation of the play was broadcast on BBC Two in 2017. Other plays include Snowflake (Old Fire Station and Kiln Theatre); Wild; An Intervention; Bull (won the Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre); an adaptation of Medea; Chariots of Fire; 13; Decade (co-writer); Earthquakes in London; Love, Love, Love; Cock (Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre); Contractions and My Child Artefacts. -

March 2009.Pmd

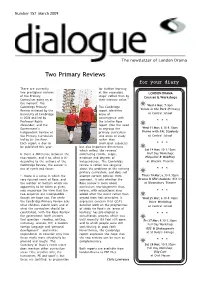

Number 157 March 2009 The newsletter of London Drama Two Primary Reviews for your diary There are currently for further learning two prestigious reviews at the secondary LONDON DRAMA of the Primary stage’ rather than by Courses & Workshops Curriculum going on at their intrinsic value.” the moment: The Wed 4 Mar; 7-9pm Cambridge Primary The Cambridge Voices in the Park (Primary) Review initiated by the report identifies University of Cambridge areas of at Central School in 2006 and led by convergence with Professor Robin the interim Rose * * * Alexander; and the report (like the need Government’s to regroup the Wed 11 Mar; 6.30-8.30pm Independent Review of primary curriculum Drama with EAL Students the Primary Curriculum into areas of study at Central School led by Sir Jim Rose. rather than Each report is due to traditional subjects) * * * be published this year. but also important differences which reflect the reviews’ Sat 14 Mar; 10-1.15pm Is there a difference between the contrasting remits, scope, Half Day Workshop: two reports, and if so, what is it? evidence and degrees of Hoipolloi & WebPlay According to the authors of the independence. The Cambridge at Unicorn Theatre Cambridge Review, the answer is review is rather less sanguine one of remit and focus: about the problems of the existing * * * primary curriculum, and does not “..there is a sense in which the exempt current policies from Thurs 19 Mar; 6.30-8.30pm very focused remit of Rose, and comment. It asks whether the Drama & SEN students (KS1/2) the number of matters which are Rose review is more about at Bloomsbury Theatre apparently to be taken as given, curriculum rearrangement than may encourage the view that the reform, with educational aims * * * two enquiries are incompatible – added after the event rather than though we hope not. -

Restoration Drama Investment in West End Theatre Buildings January 2008

Economic Development, Culture, Sport and Tourism Committee Restoration Drama Investment in West End theatre buildings January 2008 Economic Development, Culture, Sport and Tourism Committee Restoration Drama Investment in West End theatre buildings January 2008 Copyright Greater London Authority January 2008 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978 1 84781 138 7 This publication is printed on recycled paper Cover photograph: © Ian Grundy 2 Contents Rapporteur’s foreword 4 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 7 Part one There has been only limited investment to date in West End theatre buildings and more investment is required 9 Part two There may be a case for some public investment in West End theatre buildings but only on a theatre-by-theatre basis 14 Part three A number of solutions will need to be pursued to secure investment in West End theatre buildings 19 Conclusion and follow-up 26 Summary of recommendations 27 Endnotes 28 Annexes Annex A: List of 40 commercial West End theatre buildings. their owners and developments since Art Now! report (2003) 31 Annex B: Details of Mayor’s Economic Development Strategy 35 Annex C: Details of the review 36 Annex D: Principles of London Assembly scrutiny 38 Annex E: Orders and translations 39 3 Rapporteur’s foreword London’s West End Theatres are an essential part of the lifeblood of London’s tourist trade, generating £1.5 billion for London’s economy each year. The theatres have experienced record audiences this year but, despite this, most theatre owners have not invested in the fabric of the buildings. -

Croydon Borouigh of Culture 2023 Discussion Paper

CROYDON BOROUGH OF CULTURE 2023 Discussion paper following up Croydon Culture Network meeting 25 February 2020 Contents: Parts 1 Introduction 2 Croydon Council and Culture 3 The Importance of Croydon’s Cultural Activists 4 Culture and Class 5 Croydon’s Economic and Social Realities and Community 6 The Focus on Neighbourhoods 7 Audiences and Participants for 2023 8 The Relevance of Local History 9 Croydon’s Musical Heritage 10 Croydon Writers and Artists 11 Environment and Green History 12 The Use of Different Forms of Cultural Output 13 Engaging Schools 14 The Problem of Communication and the role of venues 15 System Change and Other Issues Appendices 1 An approach to activity about the environment and nature 2 Books relevant to Croydon 3 Footnotes Part 1. Introduction 1. The Culture Network meeting raised a number important issues and concerns that need to be addressed about the implementation of the award of Borough of Culture 2023 status. This is difficult as the two planning meetings that were announced would take place in March and April are not going ahead because of the coronavirus emergency. That does not mean that debate should stop. Many people involved in the Network will have more time to think about it as their events have been cancelled. Debate can take place by email, telephone, Skype, Zoom, etc. Several of the issues and concerns relate to overall aims of being Borough of Culture, as well as practical considerations. 2. There are several tensions and contradictions within the proposals that clearly could not be ironed out at the time the bid was submitted to the Mayor of London. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Thursday 26 November, 7.30pm Friday 27 November, 2pm & 7.30pm Saturday 28 November, 7.30pm A Midsummer Night’s Dream By William Shakespeare Suba Das director Guildhall School of Music & Drama Milton Court Founded in 1880 by the Situated across the road from Guildhall City of London Corporation School’s Silk Street building, Milton Court offers the School state-of-the-art Chairman of the Board of Governors performance and teaching spaces. Milton Vivienne Littlechild Court houses a 608-seat Concert Hall, a 223-seat theatre, a Studio theatre, three Principal major rehearsal rooms and a TV studio suite. Lynne Williams Students, staff and visitors to the School experience outstanding training spaces as Vice-Principal & Director of Drama well as world-class performance venues. Orla O’Loughlin Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk Photographs of the final year acting company are by: David Buttle (Charlie Beck, Lily Hardy, Hope Kenna, Isla Lee, Noah Marullo, Umi Myers, Felix Newman, Jidé Guildhall School is part of Culture Mile: Okunola, Sonny Pilgrem, Alyth Ross), Samuel Black (Dan culturemile.london Wolff), Harry Livingstone (Nia Towle), Wolf Marloh (Zachary Nachbar-Seckel), Clare Park (Grace Cooper Milton), Phil Sharp (Kitty Hawthorne, Sam Thorpe-Spinks), Michael Shelford (Levi Brown, Sheyi Cole, Aoife Gaston, Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Brandon Grace, Conor McLeod, Hassan Najib, Millie Smith, Corporation as part of its Tara Tijani, Dolly LeVack), David Stone (Justice Ritchie), contribution to the cultural life Faye Thomas (Caitlin Ffion Griffiths, Genevieve Lewis) of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare Suba Das director Grace Smart designer Ed Lewis composer Lucy Cullingford movement director Jack Stevens lighting designer Thomas Dixon sound designer Thursday 26, Friday 27, Saturday 28 November 2020 Live performances broadcast from Milton Court Theatre Recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. -

A Career Overview 2019

ELAINE PAIGE A CAREER OVERVIEW 2019 Official Website: www.elainepaige.com Twitter: @elaine_paige THEATRE: Date Production Role Theatre 1968–1970 Hair Member of the Tribe Shaftesbury Theatre (London) 1973–1974 Grease Sandy New London Theatre (London) 1974–1975 Billy Rita Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (London) 1976–1977 The Boyfriend Maisie Haymarket Theatre (Leicester) 1978–1980 Evita Eva Perón Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1981–1982 Cats Grizabella New London Theatre (London) 1983–1984 Abbacadabra Miss Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith Williams/Carabosse (London) 1986–1987 Chess Florence Vassy Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1989–1990 Anything Goes Reno Sweeney Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1993–1994 Piaf Édith Piaf Piccadilly Theatre (London) 1994, 1995- Sunset Boulevard Norma Desmond Adelphi Theatre (London) & then 1996, 1996– Minskoff Theatre (New York) 19981997 The Misanthrope Célimène Peter Hall Company, Piccadilly Theatre (London) 2000–2001 The King And I Anna Leonowens London Palladium (London) 2003 Where There's A Will Angèle Yvonne Arnaud Theatre (Guildford) & then the Theatre Royal 2004 Sweeney Todd – The Demon Mrs Lovett New York City Opera (New York)(Brighton) Barber Of Fleet Street 2007 The Drowsy Chaperone The Drowsy Novello Theatre (London) Chaperone/Beatrice 2011-12 Follies Carlotta CampionStockwell Kennedy Centre (Washington DC) Marquis Theatre, (New York) 2017-18 Dick Whttington Queen Rat LondoAhmansen Theatre (Los Angeles)n Palladium Theatre OTHER EARLY THEATRE ROLES: The Roar Of The Greasepaint - The Smell Of The Crowd (UK Tour) -

Caribbean Theatre: a PostColonial Story

CARIBBEAN THEATRE: A POSTCOLONIAL STORY Edward Baugh I am going to speak about Caribbean theatre and drama in English, which are also called West Indian theatre and West Indian drama. The story is one of how theatre in the English‐speaking Caribbean developed out of a colonial situation, to cater more and more relevantly to native Caribbean society, and how that change of focus inevitably brought with it the writing of plays that address Caribbean concerns, and do that so well that they can command admiring attention from audiences outside the Caribbean. I shall begin by taking up Ms [Chihoko] Matsuda’s suggestion that I say something about my own involvement in theatre, which happened a long time ago. It occurs to me now that my story may help to illustrate how Caribbean theatre has changed over the years and, in the process, involved the emergence of Caribbean drama. Theatre was my hobby from early, and I was actively involved in it from the mid‐Nineteen Fifties until the early Nineteen Seventies. It was never likely to be more than a hobby. There has never been a professional theatre in the Caribbean, from which one could make a living, so the thought never entered my mind. And when I stopped being actively involved in theatre, forty years ago, it was because the demands of my job, coinciding with the demands of raising a family, severely curtailed the time I had for stage work, especially for rehearsals. When I was actively involved in theatre, it was mainly as an actor, although I also did some Baugh playing Polonius in Hamlet (1967) ― 3 ― directing.