Roy Williams Has Been Quoted in the Guardian Saying: "We Only Ever Get

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

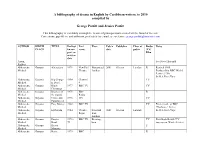

A Bibliography of Drama in English by Caribbean Writers, to 2010 Compiled By

A bibliography of drama in English by Caribbean writers, to 2010 compiled by George Parfitt and Jessica Parfitt This bibliography is inevitably incomplete. A note of principal sources used will be found at the end. Corrections, gap-fillers, and additions, preferably by e-mail, are welcome: [email protected] AUTHOR BIRTH TITLE Earliest Perf Place Pub’n Publisher Place of Radio Notes PLACE known venue date pub’n /TV/ perf. or Film written date Aaron, See Steve Hyacinth Philbert Abbensetts, Guyana Alterations 1978 New End Hampstead 2001 Oberon London R Revised 1985. Michael Theatre London Produced for BBC World Service 1980. In M.A.Four Plays Abbensetts, Guyana Big George 1994 Channel TV Michael Is Dead 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Black 1977 BBC TV TV Michael Christmas Abbensetts, Guyana Brothers of 1978 BBC R Michael the Sword Radio Abbensetts, Guyana Crime and 1976 ITV TV Michael Punishment Abbensetts, Guyana Easy Money 1982 BBC TV TV First episode of BBC Michael ‘Playhouse’ Series Abbensetts, Guyana El Dorado 1984 Theatre Stratford 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Royal East, London Abbensetts, Guyana Empire 1978 - BBC TV Birming- TV First black British T.V. Michael Road 79 ham soap opera. Wrote 2 series Abbensetts, Guyana Heavy F Michael Manners Abbensetts, Guyana Home 1975 BBC R Michael Again Radio Abbensetts, Guyana In The 1981 Hamp- London 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Mood stead Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Inner City 1975 Granada Manchest- TV Episode One of ‘Crown Michael Blues TV er Court’ Abbensetts, Guyana Little 1994 Channel TV 4-part drama Michael Napoleons 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Outlaw 1983 Arts Leicester Michael Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Roadrunner 1977 ITV TV First episode of ‘ITV Michael Playhouse’ series Abbensetts, Guyana Royston’s 1978 BBC TV Birming- 1988 Heinemann London TV Episode 4, Series 1 of Michael Day ham Empire Road. -

An Examination of Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Monica Ali's Brick Lane

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:3 March 2019 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== Stereotyping the Migrant as the ‘Other’: An Examination of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Monica Ali’s Brick Lane Sizina Joseph. M.A., B.Ed., N.E.T. (English) Ph.D. Research Scholar Higher Secondary School Teacher – English Govt. Model Residential Higher Secondary School, Munnar Kerala, India [email protected] Dr. D. Radharamanan Pillai Professor, Department of English NSS Law College, Kottiyam Kerala, India [email protected] =============================================================== Abstract In the migrant-native interface that forms the context of the narrative of diaspora novels, how is the migrant represented? The diaspora writer having been a migrant himself, do personal experiences spill into his writing or does the writer have a specific design in representing the migrant? Is there a pattern to the migrant-representation in ‘White Teeth’ and ‘Brick Lane’? What could have driven this pattern, if there is one? Is the pattern akin to stereotyping? This paper finds answers to these questions – which could lead to conclusions about the representation of the migrant in diaspora writing. Keywords: Zadie Smith, White Teeth, Monica Ali, Brick Lane, Stereotyping, Othering, Migrant, Diaspora, Orient, Occident The vindication of the project of colonization relied on depictions of the colonized as inferior, uncivilized and needing reform. Colonial discourse propagated views which created and established the coloniser-colonised binary and its parallels in the East-West and orient-occident dyads. The coloniser-colonised binary rested on a superior-inferior hierarchy, to maintain which stereotyping the colonized and, thereby, Othering them was a prerequisite. -

The Key Lessons Learnt from Producing the ABC Programme Talking

The key lessons learnt from producing the ABC programme Talkin g Heads a talk show/documentary hybrid in a fast turnaround environment Jack King HND: Business Studies (Aston Birmingham) This exegesis is submitted as the written component for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Film and Television Production: Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2009 Supervisors: Associate Professor Geoff Portmann and Associate Professor Alan McKee Abstract The following exegesis will detail the key advantages and disadvantages of combining a traditional talk show genre with a linear documentary format using a small production team and a limited budget in a fast turnaround weekly environment. It will deal with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation series Talking Heads, broadcast weekly in the early evening schedule for the network at 18.30 with the presenter Peter Thompson. As Executive Producer for the programme at its inception I was responsible for setting it up for the ABC in Brisbane, a role that included selecting most of the team to work on the series and commissioning the music, titles and all other aspects required to bring the show to the screen. What emerged when producing this generic hybrid will be examined at length, including: The talk show/documentary hybrid format needs longer than 26’30” to be entirely successful. The type of presenter ideally suited to the talk show/documentary format requires someone who is genuinely interested in their guests and flexible enough to maintain the format against tangential odds. The use of illustrative footage shot in a documentary style narrative improves the talk show format. -

IT's NOT FUNNY AFTER ALL THEY EARNED THEIR WINGS This Issue

ISSUE 3 S p r i n g This Issue 2 0 2 0 It’s Not Funny Afterall P.1 College Men & Residence Life P.2 You Earned Your Wings P.3 THEY EARNED Making the Grade Went Viral P.4 THEIR WINGS Blue Devil in Orange Tiger Country P.5 The following Differences Between Men and Women P.6 registered participants 5th Annual Dads Matter Too Conference P.7 of the Brotherhood Ropes to Courage P.8 Initiative earned a 3.0 In the Spotlight P.10 or better for the fall Bassett Update P.13 2019 semester (p. 3) Bassett Humanitarian Award Recipient P.14 Mr. Anas Alomari IT’S NOT FUNNY AFTER ALL and/or disparaging them for their gender Miss. Edith Anger by William Fothergill was accepted and seen as humorous. We all Miss. Tara Brooks Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, I laughed, and probably never really thought Mr. Cameron Clark had the opportunity to catch up on my about the power of the hidden message. We Mr. Eric Desmarais television viewing. I am not sure if this was a laughed when Edith Bunker (Jean Stapleton) good or bad thing, but it provided me with was called a “dingbat” by her tv husband Dr. Byron Dickens the opportunity to do what social scientist Archie on the sitcom All in the Family. We all Mr. Mahmoud Elassy loves to do – observe. It only took a few days laughed at Chrissy (Suzanne Somers), on the Mr. Joseph Gohar to remind myself about the biases that exist show Three is Company, when she was depicted as the embodiment of a “dumb in the media. -

By Roger Inman Greg Smith Television Production Handbook

Television Production Handbook By Roger Inman Greg Smith Television Production Handbook By Roger Inman Greg Smith ©1981-2006 Roger Inman & Greg Smith. All rights reserved. Television Production Manual ii Television Production Manual INTRODUCTION There are essentially two ways of doing television. Programs are shot either in a specially designed television studio using several cameras which are fed into a control room and assembled in "real time," or they are shot using a single camera on location and assembled later in an editing room or on a computer. Obviously, almost all non-professional video is shot using a single camera. That makes it what the pros call "electronic field production," or EFP. In electronic field production, the director is like a composer of music, creating and assembling images and impressions, fitting them together carefully, weighing the quality and importance of each as he goes. He works much as a film director would, in a linear fashion from one shot to the next, one scene to the next. He is dealing with only one picture and one situation at a time. Since the program will be edited later, he can shoot out of sequence, repeat shots, and record extra shots to be included later. Electronic field production allows for a richness of scene and artistic creativity born sometimes out of necessity and sometimes out of opportunities suggested by the location itself. Professionals spend most of their time planning, scripting, and organizing their productions. The amount of time spent actually recording the program is surprisingly short compared to the time spent preparing for it. -

Chicago's Goodman Theatres the Transition from a Division of the Art Institute of Chicago to an Independent Regional Theatre

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Everybody Loves Raymond” Let’S Shmues--Chat

THANKSGIVING WITH THE CAST OF “EVERYBODY LOVES RAYMOND” LET’S SHMUES--CHAT The Yiddish word for “turkey” is “indik.” “Dankbar” is the Yiddish word for “thankful.” By MARJORIE GOTTLIEB WOLFE 46 “milyon” turkeys are eaten each Thanksgiving. Turkey consumption has increased 104% since 1970. And 88% of Americans surveyed by the National Turkey Federation eat turkey on this holiday. Marie Barone (Doris Roberts) is devoted to making sure her boys are well-fed. She gets her adult children back with food. It’s like a culinary hostage trade-off. Marie wants Debra, her daughter-in-law, to be a better cook. She calls her “cooking-challenged” and thinks that she should live directly opposite Zabar’s. Marie want the children to have better food. She says, “A mother’s love for her sons is a lot like a dog’s piercing bark: protective, loyal, and impossible to ignore. Many episodes of “Everybody Loves Raymond” dealt with Thanksgiving. Grab a #2 pencil and see if you can identify which of the following story lines is real or fabricated. Good luck. EPISODE 1. Thanksgiving has arrived. Marie is on a “diete.” She has just returned from a residential treatment facility for weight (“vog”) loss at Duke University in North Carolina. It was an expensive (“tayer”) program. The lockdown began: Low-Fat, No-Sugar (“tsuker”), No Taste foods, and 750 calories a day. (That’s the equivalent of a slice of chocolate cake.) One woman in the program sent herself “Candygrams” each week (“vokh”). Doris eats very little (“a bisl”) at the Thanksgiving table, but as she is preparing to leave Debra’s house, she asks for a little leftover turkey and apple (“epl”) chutney. -

Lee Sharp Mixer Landscape

LEE SHARP A.M.P.S. SOUND RECORDIST MSc Sound Design, University of Edinburgh Tel. 07929-474-502 E. [email protected] Web. www.sharpsound.co.uk Available throughout the UK and overseas IMDb: Lee Sharp TELEVISION AND FEATURES TITLE PRODUCTION COMPANY DIRECTOR PRODUCER OUTSIDE OUTSIDE MOVIE COMPANY ROMOLA GARAI MATTHEW JAMES WILKINSON FREE REIN - SEASON 3 (2nd Unit) LIME PICTURES / NETFLIX MAX MYERS ANGELO ABELA A TOUR WITH KEVIN HART NETFLIX KEVIN HART NEAL MARSHALL KILLERS ANONYMOUS RISE PRODUCTIONS MARTIN OWEN MATT WILLS HONKY TONK (WORKING TITLE) UNION PICTURES DAVID REES ROBYN FORSYTHE THE LAST TESTAMENT OF LILLIAN BILOCCA NORTHERN FILMS MAXINE PEAKE VANESSA STOCKLEY ENHANCED ESPN FILMS PAUL TAUBLIEB JOHN JORDAN A CHRISTMAS CAROL BBC FILMS TOM CAIRNS LESLEY STEWART OUTLAW KING (Sound Recordist: Main Unit Additional) SIGMA FILMS / NETFLIX DAVID MACKENZIE STAN WLODKOWSKI BREXIT SHORTS: SHATTERED THE GUARDIAN MAXINE PEAKE LAURENCE TOPHAM CEREMONY: THE RETURN OF FRIEDRICH ENGELS TIGERLILY NATASHA DACK OJUMU PHIL COLLINS ENGLAND IS MINE HONLODGE PRODUCTIONS MARK GILL BALDWIN LI BATMAN ARKHAM VR ROCKSTEADY STUDIOS SEFTON HILL NATHAN BURLOW WALK LIKE A PANTHER (2ND Unit) FOX INTERNATIONAL (UK) DAN CADAN DEAN O’TOOLE AHIR SHAH’S SUMMER KING BERT/ SKY ATLANTIC CHRISTOPHER SWEENY MADELINE ADDY JOCELYN JEE ESIEN’S SUMMER KING BERT / SKY ATLANTIC CHRISTOPHER SWEENY MADELINE ADDY THE LATE LATE SHOW: UK FULWELL 73 GLEN CLEMENTS CARLY SHACKLETON NATIONAL TREASURE (2nd Unit) THE FORGE MARC MUNDEN JOHN CHAPMAN BOOGIE MAN (Additional Photography) GLOBALWATCH ANDREW MORAHAN PAUL ANDREWS WHISKY GALORE (2nd Unit) WHISKEY GALORE GILLIES MCKINNON WILLY WAND LEE SHARP A.M.P.S. -

Everybody Loves Raymond

SHOW BIZ Maria Faisal Everybody Loves Raymond Based on the real-life experiences of Ray Romano, Everybody Loves Raymond, the popular sitcom ran from September 1996 to May 2005. Everybody Loves Raymond, a very popular American sitcom broadcast on CBS, ran from 1996 to 2005. The show revolved around the life of Ray Barone, a News Paper sportswriter from Long Island, his wife, Debra, daughter, Ally, and identical twin sons, Geoffrey and Michael. Ray has imposing parents and a jealous, insecure brother, Robert. They are found most of the time in the living room of Ray. Debra, Ray's wife is sick of this routine that had turned her in to a cranky yelling woman, but tolerates for the love of her husband. Ray’s parents and brother never give Ray or his family a moment of peace. Ray often finds himself in the middle of someone else's problems. He is usually the one blamed for everyone else's troubles. Based on the real-life experiences of Ray Romano, Everybody Loves Raymond premiered on September 13, 1996, on CBS. The series finale was broadcast on May 16, 2005, though old episodes are still rerun on cable network TBS and in daily syndication. The show can be watched Monday to Friday on Rogers channel 35, 835, 47 and 847. Paaras 1 Interesting Facts About the Show ·In an unusual turn for such a long-running show, ·Like Robert Barone in Everybody Loves Raymond, every episode featured a single plotline followed Ray Romano has a brother who works for the New throughout both acts. -

Lee Sharp Amps

LEE SHARP A.M.P.S. SOUND RECORDIST MSc Sound Design, University of Edinburgh Tel. 07929-474-502 E. [email protected] Web. www.sharpsound.co.uk Available throughout the UK and overseas IMDb: Lee Sharp TELEVISION AND FEATURES TITLE PRODUCTION COMPANY DIRECTOR PRODUCER MEET THE RICHARDSONS - SERIES 1 2NDACT / ITV STUDIOS EDDIE STAFFORD PIP HADDOW SPORT ENGLAND - DOCUMENTARY KNUCKLEHEAD JJ AUGUSTAVO FRANCIS MILDMAY-WHITE THE LOVE SQUAD - SERIES 1 WORKER BEE / MTV DAVID KANGAS SEAN MURPHY EGGS COLLECTIVE: SMILE LOVE, IT MAY NEVER HAPPEN BBC ARTS REBECCA RYCROFT REBECCA RYCROFT LEVIS MUSIC PROJECT WITH LOYLE CARNER WARNER MUSIC WILL WILLIAMSON ABI BEASLEY AMULET HEAD GEAR FILMS ROMOLA GARAI MATTHEW JAMES WILKINSON FREE REIN - SEASON 3 (2nd Unit) LIME PICTURES / NETFLIX MAX MYERS ANGELO ABELA KEVIN HART: iRRESPONSIBLE NETFLIX KEVIN HART NEAL MARSHALL KILLERS ANONYMOUS RISE PRODUCTIONS MARTIN OWEN MATT WILLS LOOK THE OTHER WAY AND RUN UNION PICTURES DAVID REES ROBYN FORSYTHE THE LAST TESTAMENT OF LILLIAN BILOCCA NORTHERN FILMS MAXINE PEAKE VANESSA STOCKLEY ENHANCED ESPN FILMS PAUL TAUBLIEB JOHN JORDAN A CHRISTMAS CAROL BBC FILMS TOM CAIRNS LESLEY STEWART OUTLAW KING (Sound Recordist: Main Unit Additional) SIGMA FILMS / NETFLIX DAVID MACKENZIE STAN WLODKOWSKI BREXIT SHORTS: SHATTERED THE GUARDIAN MAXINE PEAKE LAURENCE TOPHAM CEREMONY: THE RETURN OF FRIEDRICH ENGELS TIGERLILY NATASHA DACK OJUMU PHIL COLLINS ENGLAND IS MINE HONLODGE PRODUCTIONS MARK GILL BALDWIN LI BATMAN ARKHAM VR ROCKSTEADY STUDIOS SEFTON HILL NATHAN BURLOW WALK LIKE A PANTHER (2ND Unit) FOX INTERNATIONAL (UK) DAN CADAN DEAN O’TOOLE AHIR SHAH’S SUMMER KING BERT/ SKY ATLANTIC CHRISTOPHER SWEENY MADELINE ADDY JOCELYN JEE ESIEN’S SUMMER KING BERT / SKY ATLANTIC CHRISTOPHER SWEENY MADELINE ADDY THE LATE LATE SHOW: UK FULWELL 73 GLEN CLEMENTS CARLY SHACKLETON LEE SHARP A.M.P.S. -

The British Academy Television Awards Sponsored by Pioneer

The British Academy Television Awards sponsored by Pioneer NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED 11 APRIL 2007 ACTOR Programme Channel Jim Broadbent Longford Channel 4 Andy Serkis Longford Channel 4 Michael Sheen Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC4 John Simm Life On Mars BBC1 ACTRESS Programme Channel Anne-Marie Duff The Virgin Queen BBC1 Samantha Morton Longford Channel 4 Ruth Wilson Jane Eyre BBC1 Victoria Wood Housewife 49 ITV1 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway ITV1 Stephen Fry QI BBC2 Paul Merton Have I Got News For You BBC1 Jonathan Ross Friday Night With Jonathan Ross BBC1 COMEDY PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Dawn French The Vicar of Dibley BBC1 Ricky Gervais Extra’s BBC2 Stephen Merchant Extra’s BBC2 Liz Smith The Royle Family: Queen of Sheba BBC1 SINGLE DRAMA Housewife 49 Victoria Wood, Piers Wenger, Gavin Millar, David Threlfall ITV1/ITV Productions/10.12.06 Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! Andy de Emmony, Ben Evans, Martyn Hesford BBC4/BBC Drama/13.03.06 Longford Peter Morgan, Tom Hooper, Helen Flint, Andy Harries C4/A Granada Production for C4 in assoc. with HBO/26.10.06 Road To Guantanamo Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross C4/Revolution Films/09.03.06 DRAMA SERIES Life on Mars Production Team BBC1/Kudos Film & Television/09.01.06 Shameless Production Team C4/Company Pictures/01.01.06 Sugar Rush Production Team C4/Shine Productions/06.07.06 The Street Jimmy McGovern, Sita Williams, David Blair, Ken Horn BBC1/Granada Television Ltd/13.04.06 DRAMA SERIAL Low Winter Sun Greg Brenman, Adrian Shergold, -

Limitations on Copyright Protection for Format Ideas in Reality Television Programming

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING By Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen* * Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen are partners in the Entertainment, Media, and Technology Group in the Century City, California and Washington, D.C. offices, respectively, of Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP. The authors thank Ben Aigboboh, an associate in the Century City office, for his assistance with this article. 97 For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING I. INTRODUCTION Television networks constantly compete to find and produce the next big hit. The shifting economic landscape forged by increasing competition between and among ever-proliferating media platforms, however, places extreme pressure on network profit margins. Fully scripted hour-long dramas and half-hour comedies have become increasingly costly, while delivering diminishing ratings in the key demographics most valued by advertisers. It therefore is not surprising that the reality television genre has become a staple of network schedules. New reality shows are churned out each season.1 The main appeal, of course, is that they are cheap to make and addictive to watch. Networks are able to take ordinary people and create a show without having to pay “A-list” actor salaries and hire teams of writers.2 Many of the most popular programs are unscripted, meaning lower cost for higher ratings. Even where the ratings are flat, such shows are capable of generating higher profit margins through advertising directed to large groups of more readily targeted viewers.