WRAP THESIS Johnson1 2001.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

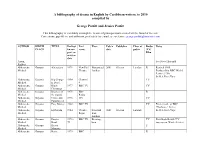

A Bibliography of Drama in English by Caribbean Writers, to 2010 Compiled By

A bibliography of drama in English by Caribbean writers, to 2010 compiled by George Parfitt and Jessica Parfitt This bibliography is inevitably incomplete. A note of principal sources used will be found at the end. Corrections, gap-fillers, and additions, preferably by e-mail, are welcome: [email protected] AUTHOR BIRTH TITLE Earliest Perf Place Pub’n Publisher Place of Radio Notes PLACE known venue date pub’n /TV/ perf. or Film written date Aaron, See Steve Hyacinth Philbert Abbensetts, Guyana Alterations 1978 New End Hampstead 2001 Oberon London R Revised 1985. Michael Theatre London Produced for BBC World Service 1980. In M.A.Four Plays Abbensetts, Guyana Big George 1994 Channel TV Michael Is Dead 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Black 1977 BBC TV TV Michael Christmas Abbensetts, Guyana Brothers of 1978 BBC R Michael the Sword Radio Abbensetts, Guyana Crime and 1976 ITV TV Michael Punishment Abbensetts, Guyana Easy Money 1982 BBC TV TV First episode of BBC Michael ‘Playhouse’ Series Abbensetts, Guyana El Dorado 1984 Theatre Stratford 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Royal East, London Abbensetts, Guyana Empire 1978 - BBC TV Birming- TV First black British T.V. Michael Road 79 ham soap opera. Wrote 2 series Abbensetts, Guyana Heavy F Michael Manners Abbensetts, Guyana Home 1975 BBC R Michael Again Radio Abbensetts, Guyana In The 1981 Hamp- London 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Mood stead Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Inner City 1975 Granada Manchest- TV Episode One of ‘Crown Michael Blues TV er Court’ Abbensetts, Guyana Little 1994 Channel TV 4-part drama Michael Napoleons 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Outlaw 1983 Arts Leicester Michael Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Roadrunner 1977 ITV TV First episode of ‘ITV Michael Playhouse’ series Abbensetts, Guyana Royston’s 1978 BBC TV Birming- 1988 Heinemann London TV Episode 4, Series 1 of Michael Day ham Empire Road. -

Theatre Reviews

REVIEWERS Imke Lichterfeld, Erica Sheen INITIATING EDITOR Mateusz Grabowski TECHNICAL EDITOR Zdzisław Gralka PROOF-READER Nicole Fayard COVER Alicja Habisiak Task: Increasing the participation of foreign reviewers in assessing articles approved for publication in the semi-annual journal Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance financed through contract no. 605/P-DUN/2019 from the funds of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education devoted to the promotion of scholarship Printed directly from camera-ready materials provided to the Łódź University Press © Copyright by Authors, Łódź 2019 © Copyright for this edition by University of Łódź, Łódź 2019 Published by Łódź University Press First Edition W.09355.19.0.C Printing sheets 12.0 ISSN 2083-8530 Łódź University Press 90-131 Łódź, Lindleya 8 www.wydawnictwo.uni.lodz.pl e-mail: [email protected] phone (42) 665 58 63 Contents Contributors ................................................................................................... 5 Nicole Fayard, Introduction: Shakespeare and/in Europe: Connecting Voices ................................................................................................ 9 Articles Nicole Fayard, Je suis Shakespeare: The Making of Shared Identities in France and Europe in Crisis .......................................................... 31 Jami Rogers, Cross-Cultural Casting in Britain: The Path to Inclusion, 1972-2012 .......................................................................................... 55 Robert -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Future Watch – Setting the Stage for Regeneration

http://www.architectsdatafile.co.uk/news/future-watch-setting-the-stage-for- regeneration/ Thursday, 30th November 2017 Future Watch – Setting the stage for regeneration Tim Foster With cities’ night time economy being seen as increasingly important in the future, Tim Foster, partner at Foster Wilson Architects, reflects on how theatre design projects that put placemaking at their core can catalyse regeneration. Following the debate around placemaking in recent years it is apparent that the term means many different things to different people. Local community activists believe it is about community participation and the making of places in which people have ownership, while property people believe it is about creating a congenial environment which will attract people to their developments, making them easier to sell or rent for a good return: the reality probably lies somewhere in between. As quoted in a recent article in The Guardian, the US academic Richard Florida – considered to be the guru of placemaking – told the mayors of major American cities in 2002 that attracting ‘hipsters’ to their towns was crucial. “Don’t waste money on stadiums and concert halls, or luring big companies with tax breaks. Instead, make your town a place where hipsters want to be, with a vibrant arts and music scene and a lively cafe culture. Embrace the ‘three T’s’ of technology, talent and tolerance, and the ‘creative class’ will come flocking.” This is really the same cycle that Jane Jacobs described in her seminal work ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities’, published in 1961, whereby districts fall into decay, the artists move in attracted by the cheap rents, the hipsters and coffee shops follow, the area regenerates, forcing the rents back up and the artists and original residents to move on. -

Caribbean Theatre: a PostColonial Story

CARIBBEAN THEATRE: A POSTCOLONIAL STORY Edward Baugh I am going to speak about Caribbean theatre and drama in English, which are also called West Indian theatre and West Indian drama. The story is one of how theatre in the English‐speaking Caribbean developed out of a colonial situation, to cater more and more relevantly to native Caribbean society, and how that change of focus inevitably brought with it the writing of plays that address Caribbean concerns, and do that so well that they can command admiring attention from audiences outside the Caribbean. I shall begin by taking up Ms [Chihoko] Matsuda’s suggestion that I say something about my own involvement in theatre, which happened a long time ago. It occurs to me now that my story may help to illustrate how Caribbean theatre has changed over the years and, in the process, involved the emergence of Caribbean drama. Theatre was my hobby from early, and I was actively involved in it from the mid‐Nineteen Fifties until the early Nineteen Seventies. It was never likely to be more than a hobby. There has never been a professional theatre in the Caribbean, from which one could make a living, so the thought never entered my mind. And when I stopped being actively involved in theatre, forty years ago, it was because the demands of my job, coinciding with the demands of raising a family, severely curtailed the time I had for stage work, especially for rehearsals. When I was actively involved in theatre, it was mainly as an actor, although I also did some Baugh playing Polonius in Hamlet (1967) ― 3 ― directing. -

EARL CAMERON Sapphire

EARL CAMERON Sapphire Reuniting Cameron with director Basil Dearden after Pool of London, and hastened into production following the Notting Hill riots of summer 1958, Sapphire continued Dearden and producer Michael Relph’s valuable run of ‘social problem’ pictures, this time using a murder-mystery plot as a vehicle to sharply probe contemporary attitudes to race. Cameron’s role here is relatively small, but, playing the brother of the biracial murder victim of the title, the actor makes his mark in a couple of memorable scenes. Like Dearden’s later Victim (1961), Sapphire was scripted by the undervalued Janet Green. Alex Ramon, bfi.org.uk Sapphire is a graphic portrayal of ethnic tensions in 1950s London, much more widespread and malign than was represented in Dearden’s Pool of London (1951), eight years earlier. The film presents a multifaceted and frequently surprising portrait that involves not just ‘the usual suspects’, but is able to reveal underlying insecurities and fears of ordinary people. Sapphire is also notable for showing a successful, middle-class black community – unusual even in today’s British films. Dearden deftly manipulates tension with the drip-drip of revelations about the murdered girl’s life. Sapphire is at first assumed to be white, so the appearance of her black brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron) is genuinely astonishing, provoking involuntary reactions from those he meets, and ultimately exposing the real killer. Small incidents of civility and kindness, such as that by a small child on a scooter to Dr Robbins, add light to a very dark film. Earl Cameron reprises a role for which he was famous, of the decent and dignified black man, well aware of the burden of his colour. -

+14 Days of Tv Listings Free

CINEMA VOD SPORTS TECH + 14 DAYS OF TV LISTINGS 1 JUNE 2015 ISSUE 2 TVGUIDE.CO.UK TVDAILY.COM Jurassic World Orange is the New Black Formula 1 Addictive Apps FREE 1 JUNE 2015 Issue 2 Contents TVGUIDE.CO.UK TVDAILY.COM EDITOR’S LETTER 4 Latest TV News 17 Food We are living in a The biggest news from the world of television. Your television dinners sorted with revolutionary age for inspiration from our favourite dramas. television. Not only is the way we watch television being challenged by the emergence of video on 18 Travel demand, but what we watch on television is Journey to the dizzying desert of Dorne or becoming increasingly take a trip to see the stunning setting of diverse and, thankfully, starting to catch up with Downton Abbey. real world demographics. With Orange Is The New Black back for another run on Netflix this month, we 19 Fashion decided to celebrate the 6 Top 100 WTF Steal some shadespiration from the arduous journey it’s taken to get to where we are in coolest sunglass-wearing dudes on TV. 2015 (p14). We still have a Moments (Part 2) long way to go, but we’re The final countdown of the most unbelievable getting there. Sports Susan Brett, Editor scenes ever to grace the small screen, 20 including the electrifying number one. All you need to know about the upcoming TVGuide.co.uk Formula 1 and MotoGP races. 104-08 Oxford Street, London, W1D 1LP [email protected] 8 Cinema CONTENT 22 Addictive Apps Editor: Susan Brett Everything you need to know about what’s Deputy Editor: Ally Russell A handy guide to all the best apps for Artistic Director: Francisco on at the Box Office right now. -

British Television's Lost New Wave Moment: Single Drama and Race

British Television’s Lost New Wave Moment: Single Drama and Race Eleni Liarou Abstract: The article argues that the working-class realism of post-WWII British television single drama is neither as English nor as white as is often implied. The surviving audiovisual material and written sources (reviews, publicity material, biographies of television writers and directors) reveal ITV’s dynamic role in offering a range of views and representations of Britain’s black population and their multi-layered relationship with white working-class cultures. By examining this neglected history of postwar British drama, this article argues for more inclusive historiographies of British television and sheds light on the dynamism and diversity of British television culture. Keywords: TV drama; working-class realism; new wave; representations of race and immigration; TV historiography; ITV history Television scholars have typically seen British television’s late- 1950s/early-1960s single drama, and particularly ITV’s Armchair Theatre strand, as a manifestation of the postwar new wave preoccupation with the English regional working class (Laing 1986; Cooke 2003; Rolinson 2011). This article argues that the working- class realism of this drama strand is neither as English nor as white as is often implied. The surviving audiovisual material and written sources – including programme listings, reviews, scripts, publicity material, biographies of television writers and directors – reveal ITV’s dynamic role in offering a range of representations of Britain’s black population and its relationship to white working-class cultures. More Journal of British Cinema and Television 9.4 (2012): 612–627 DOI: 10.3366/jbctv.2012.0108 © Edinburgh University Press www.eupjournals.com/jbctv 612 British Television’s Lost New Wave Moment particularly, the study of ITV’s single drama about black immigration in this period raises important questions which lie at the heart of postwar debates on commercial television’s lack of commitment to its public service remit. -

Equity Magazine Autumn 2020 in This Issue

www.equity.org.uk AUTUMN 2020 Filming resumes HE’S in Albert Square Union leads the BEHIND fight for the circus ...THE Goodbye, MASK! Christine Payne Staying safe at the panto parade FIRST SET VISITS SINCE THE LIVE PERFORMANCE TASK FORCE FOR COVID PANDEMIC BEGAN IN THE ZOOM AGE FREELANCERS LAUNCHED INSURANCE? EQUITY MAGAZINE AUTUMN 2020 IN THIS ISSUE 4 UPFRONT Exclusive Professional Property Cover for New General Secretary Paul Fleming talks Panto Equity members Parade, equality and his vision for the union 6 CIRCUS RETURNS Equity’s campaign for clarity and parity for the UK/Europe or Worldwide circus cameras and ancillary equipment, PA, sound ,lighting, and mechanical effects equipment, portable computer 6 equipment, rigging equipment, tools, props, sets and costumes, musical instruments, make up and prosthetics. 9 FILMING RETURNS Tanya Franks on the socially distanced EastEnders set 24 GET AN INSURANCE QUOTE AT FIRSTACTINSURANCE.CO.UK 11 MEETING THE MEMBERS Tel 020 8686 5050 Equity’s Marlene Curran goes on the union’s first cast visits since March First Act Insurance* is the preferred insurance intermediary to *First Act Insurance is a trading name of Hencilla Canworth Ltd Authorised and Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under reference number 226263 12 SAFETY ON STAGE New musical Sleepless adapts to the demands of live performance during the pandemic First Act Insurance presents... 14 ONLINE PERFORMANCE Lessons learned from a theatre company’s experiments working over Zoom 17 CONTRACTS Equity reaches new temporary variation for directors, designers and choreographers 18 MOVEMENT DIRECTORS Association launches to secure movement directors recognition within the industry 20 FREELANCERS Participants in the Freelance Task Force share their experiences Key features include 24 CHRISTINE RETIRES • Competitive online quote and buy cover provided by HISCOX. -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

Roy Williams Has Been Quoted in the Guardian Saying: "We Only Ever Get

Comedy, drama and black Britain – An interview with Paulette Randall Eva Ulrike Pirker British theatre director Paulette Randall once said about herself and her work, "I'm not a politician, and I never set out to be one. What I do believe is that if we are in the business of theatre, of art, of creating, then that has to be at the forefront. The product, the play, has to be paramount."1 A look at her creative output, however, shows her political engagement in place – not so much in the sense of taking a proffered side, but certainly in the sense of insisting on participation in the public debate. To name just a few of her recent projects: Her 2003 production of Urban Afro Saxons at the Theatre Royal Stratford East was a timely intervention in the public debate about Britishness. The staging of James Baldwin's Blues for Mr Charlie (2004) at the Tricycle Theatre provided a thought-provoking viewing experience for a British audience in the wake of the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. For the Trycicle and Talawa Theatre Company, Randall has staged four of August Wilson's plays. Her most recent theatre project was a production of Mustapha Matura's adaptation of Chekhov's Three Sisters at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 2006.2 However, Paulette Randall also has a professional life outside the theatre, where she makes her impact on the landscape of British sitcoms as a television producer. The following interview focuses not so much on specific productions, but more generally on her views on television, Britain's theatre culture, and the representations of Britain's diverse society. -

Don Warrington W1D 6LD

www.cam.co.uk Email [email protected] Address Don 55-59 Shaftesbury Avenue London Warrington W1D 6LD Telephone +44 (0) 20 7292 0600 Television Title Role Director Production THE WORLD ACCORDING TO GRANDPA Grandpa Alexander James Jacob Milkshake! DEATH IN PARADISE- All series produced Selwyn Patterson Various BBC THE FIVE Ray Kenwood Mark Tonderai Sky THE ARK Paul Red Productions BBC CHASING SHADOWS CS Drayton Jim O'Hanlon ITV LAW AND ORDER Callaghan Andy Goddard ITV LEWIS Prof Woolf David O'Neill ITV THIS IS JINSY Chief Thinker Matt Lipsey BBC WAKING THE DEAD Adam Barclay Tim Fywell BBC GOING POSTAL Priest Jon Jones SKY CASUALTY Trevor- Semi Regular Various BBC LAW & ORDER Chief Commissioner Andy Goddard ITV COMET Futureshock Keith Boak Channel 5/ Darlow Smithson NEW STREET LAW Judge Ken Winyard Various BBC/Red Productions DIAMOND GEEZER Hector Paul Harrision YTV ALL STAR COMEDY SHOW - David Evans ITV THE CROUCHES Bailey Nick Wood BBC TO PLAY THE KING Graham Gaunt Paul Seed BBC ARABIAN KNIGHTS Hari Ben Karim Steve Barron Hallmark Productions CATS EYES Nigel Beaumont Various TVS MAN CHILD Patrick Various BBC THE ARMAND IANNUCCI Ivy Diner Channel 4 Talkback TRAIL & TRIBUTION Willard Pembroke Various ITV RISING DAMP Philip Smith Various ITV Theatre Title Role Director Production DEATH OF A SALESMAN Willy Loman Sarah Frankcom Royal Exchange GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS George Aaronow Sam Yates Playhouse Theatre KING LEAR King Lear Michael Buffong Talawa Theatre Company ALL MY SONS Joe Keller Michael Buffong Manchester Royal Exchange DRIVING MISS